Are We There Yet?

Westward Exploration and Travel in North America

Checklist for "Are We There Yet?"

Curated by Luise Poulton, 2012

Exhibition poster designed by David Wolske, 2012

Digital exhibition produced by Alison Elbrader, 2013

Format updated by Lyuba Basin, 2020

Soon after the first European ship reached North American shores, emigrants from the early settlements on the east coast began exploring the vast lands to the west. Some sought a haven from religious persecution, some looked for better agricultural lands, some pursued quick wealth. Whatever the reason, emigrants believed that they could improve their lives by moving West. Many people longed to see the West, even if they didn’t want to settle there. Three hundred years of writings by travelers, politicians, explorers, emigrants, adventurers, and marketers lured people west – as seekers of a new life or merely seekers of a good time.

Travelers

“An idea, strange as it is visionary, has entered into the minds of the generality of mankind, that empire is travelling westward; and every one is looking forward with eager and impatient expectation to that destined moment, when America is to give law to the rest of the world. But if ever an idea was illusory and fallacious, I will venture to predict, that this will be so. America is formed for happiness, but not for empire.”

Andrew Burnaby traveled the North American colonies at a critical time. He witnessed the French and Indian Wars which brought about the downfall of French power in North America. His reflections on the character of the people, their manners and customs, provide an excellent view of living conditions at this time. The preface presents a long review of affairs between Britain and the colonies, with remarks in favor of leniency towards the colonies. One object of the publication of this book was to give a kindly view of the colonists as a basis for reconciliation between them and their mother country. Thomas Jefferson had a copy of this book in his personal library.

London: Printed for John Stackdale, Piccadilly, 1799

First edition

E164 W44 1799

“The passage of the rivers through the ridge at this place is certainly a curious scene, and deserving of attention; but I am far from thinking with Mr. Jefferson, that it is ‘one of the most stupendous scenes in nature, and worth a voyage across the Atlantic.’ To find numberless scenes more stupendous, it would be needless to go farther than Wales. Indeed, from every part of Mr. Jefferson’s description, it appears as if he had beheld the scene, not in its present state, but at the very moment when the disruption happened, and when every thing was in a state of tumult and confusion.”

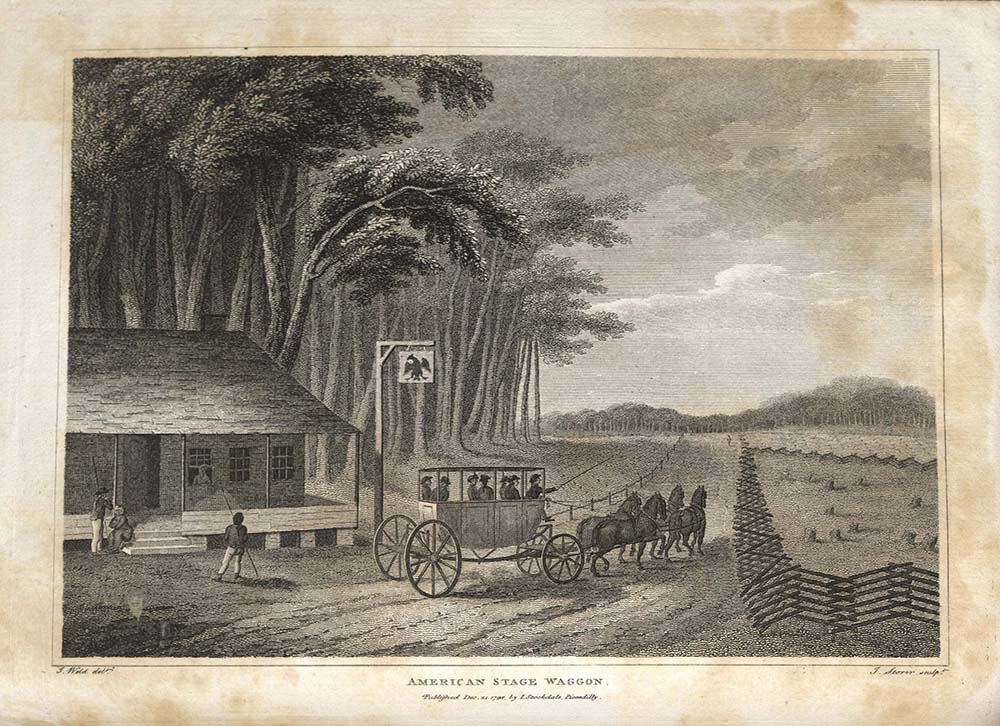

Dubliner Isaac Weld sailed to Philadelphia in 1795 and spent two years traveling the east coast of Canada and the newly formed United States on horseback, foot, and canoe along rivers and through dense forests. During his travels he met George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. One of the reasons for his trip was to find places suitable for Irish immigration. In the end, he preferred Canada to the United States, finding Americans too materialistic. Travels was very popular, quickly printed in three successive editions and translated into French, German and Dutch. It was illustrated with engravings of American scenes, such as a stagecoach pulling away from a tavern (Weld found U.S. taverns “indifferent”). University of Utah copy g

ift of Dr. Ronald Rubin.

Politicians

City of Washington, A & G. Way, printers, 1806

First edition

F592.3 1806

“…captain Meriwether Lewis, of the first regiment of infantry, was appointed, with a party of men, to explore the river Missouri, from its mouth to its source, and, crossing the highlands by the shortest portage, to seek the best water communication thence to the Pacific ocean; and lieutenant Clarke was appointed second in command. They were to enter into conference with the Indian nations on their route, with a view to the establishment of commerce with them.”

President Thomas Jefferson’s Message is the cover letter for a group of documents that report government-funded explorations in the recently acquired territory known as the “Louisiana Purchase.” Jefferson chose Meriwether Lewis, his private secretary whom he had also trained as a surveyor, to head the expedition. The purchase of land by a President was not exactly constitutional, but by this negotiation Jefferson effectively averted war with Spain. Ironically, the road West eventually meant war just the same, as thousands of Spanish descendants and indigenous peoples were destroyed by famine, disease, military and citizen ambush, and displacement. The journey of Lewis and Clark opened the West to exploration and exploitation, leaving the American Indian essentially homeless, but giving a young nation an unprecedented opportunity for expansion. Edition of one thousand copies.

Washington: 1831

First edition

F592 U5 1831

“The Rocky mountains are deemed by many to be impassable, and to present the barrier which will arrest the westward march of the American population. The man must know but little of the American people who supposes they can be stopped by any thing in the shape of mountains, deserts, seas, or rivers.”

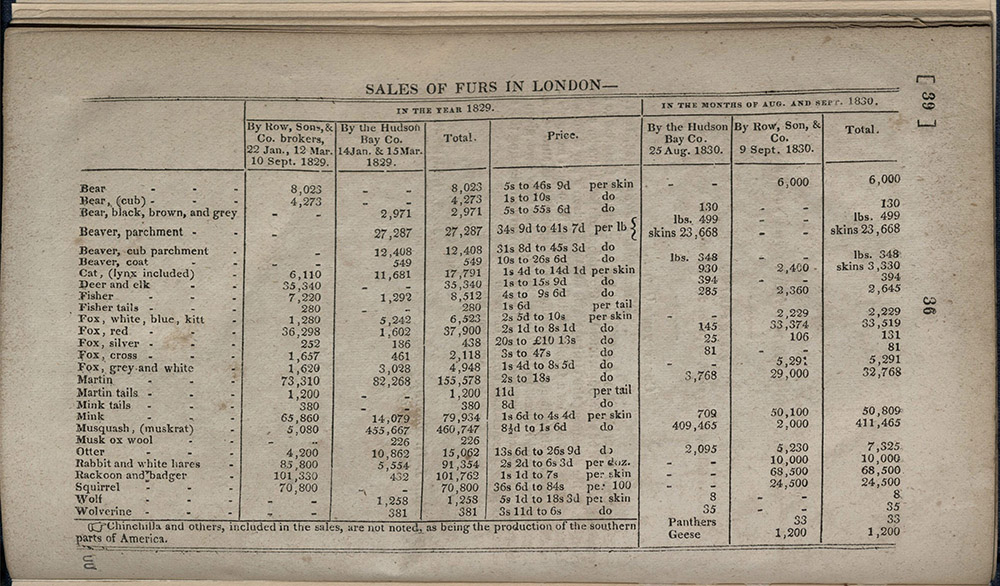

One of the most valuable accounts of European activities in the Rocky Mountains during Andrew Jackson’s presidency, this message describes the travels of Jedediah Smith and other early fur traders in Oregon and western Canada.

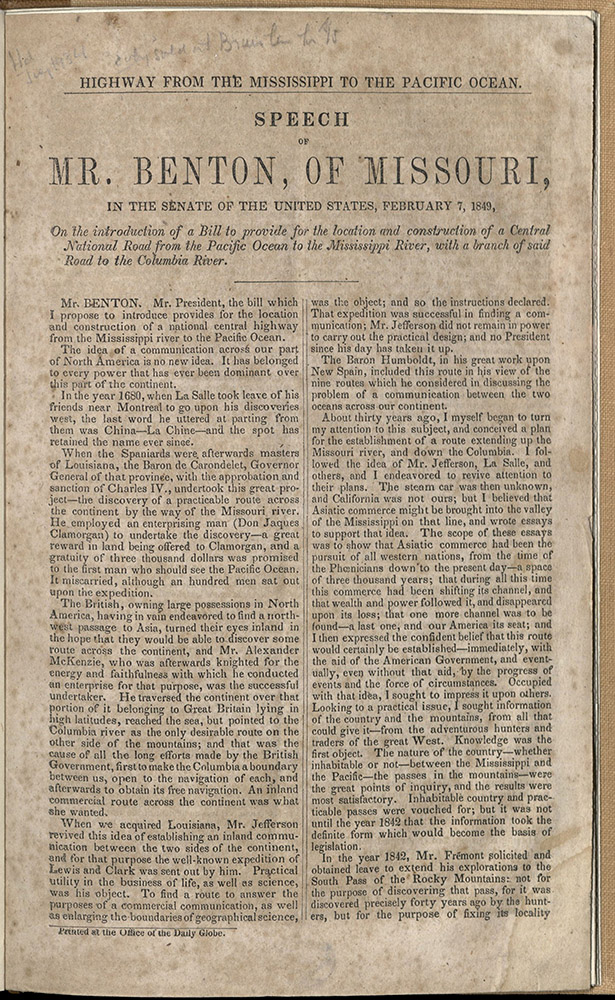

Washington: Printed at the office of the Daily Globe, 1849

HE2763 1850

“Since the discovery of the New World by Columbus there has not been such an unsettling of the foundations of society. Not merely individuals and companies, but communities and nations are in commotion, all bound to the setting sun – to the gilded horizon of Western America…An American road to India, through the heart of our country, will revive upon its line all the wonders of which we have read – and eclipse them…The state of the world calls for a new road to India, and it is our destiny to give it – the last and greatest.”

Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri spent his career promoting the authorization by the federal government of a transcontinental railroad. Benton believed that an overland trade route to the Pacific Coast would enable the United States to compete for world domination of trade with Asia.

Explorers

PASSAGE PAR TERRE A LA CALIFORNIE DECOUVERTE PAR LE P. P. EUSEBE-FRANCOIS…

Paris: F. Kino, 1705?

G4422 C3 1698 K5

This map eventually led to the end of the belief that California was an island. It shows the route taken by the Jesuit Father Eusebio Kino in 1698 when he traveled from the west coast of mainland Mexico to Baja. Observing the mouth of the Colorado River, he concluded that California was not an island, as it had been depicted in maps since 1620. Following the publication of his travel account with this map, cartographers used his findings to correctly redraw California as a peninsula, although some maps of an insular California continued to be made as late as the 1760’s.

CARTE GENERALE DES D’ECOUVERTES DE L’AMIRAL DE FONTE ET AUTRES NAVIGATEURS ESPAGNOLS ANGLOIS ET RUSSES POUR LA RECHERCHE DU PASSAGE A LA MER DU SUD

Paris: M Del Isle de l’Academie royale des sciences &c., 1752

G3300 1752 A33

Routes of 18th century navigators and the supposed “Northwest Passage.”

PARTIE DE L’AMERIQUE SEPTENT QUI COMPREND LA NOUVELLE FRANCE OU LE CANADA PAR LE SR. ROBERT DE VAUGONDY, GEOG ORDINAIRE DU ROY. AVEC PRIVILEGE 1755: E. HAUSSARD, SCULP.

Paris?, 1755

G3400 1755 R6

Pittsburgh: Printed by Zadok Cramer, for David M’Keehan, publisher and proprietor, 1807

First Edition

F592.5 G2 1807

“They found the ocean to be about 7 miles from our camp; for 4 miles the land high and closely timbered: the remainder prairies cut with some steams of water. They killed an elk and saw about 50 in one gang. They also saw three lodges of Indians on the seashore. The natives which were at our camp, went away this morning after receiving some presents. In the evening we laid the foundation of our huts.”

The publication of Patrick Gass’s journal preceded the official account of the Lewis and Clark expedition by seven years. It was the earliest first-hand description of the vast territory acquired by President Thomas Jefferson with the Louisiana Purchase and explored by Captain Meriwether Lewis, Second Lieutenant William Clark and their Corps. Several weeks after the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, President Jefferson petitioned Congress to appropriate $2500 “to send intelligent officers with ten or twelve men, to explore even to the western ocean.” Gass, a carpenter, constructed all three of the Corps’ winter lodgings as well as canoes and wagons. Gass had not learned to read or write until he was grown, but followed Lewis’ instructions to keep a detailed diary for the duration of the expedition. Upon the return of the Corps, Gass edited his account for publication, with reviews and corrections by both Lewis and Clark.

Philadelphia: Published by C. & Z. Conrad, Somervell & Conrad, Peterburgh, Bonsal, Conrad, Norfolk, and Fielding Lucas, jr., Baltimore. John Binns, printer, 1810

First edition

F592 P63

“Inside of the enclosure were the different streets of houses of the same fashion, all of one story; the doors were narrow, the windows small, and in one or two houses there were talc lights. This village has a mill near it, situated on the little creek, which made very good flour. The population consisted of civilized Indians, but much mixed blood. Here we had a dance which is called the Fandango.”

While Lewis and Clark headed northwest, Zebulon Pike began his explorations in northern Minnesota, attempting to find the source of the Mississippi River. Failing that, he was sent to explore the southwest. Pike followed the Rio Grande into Spanish territory where he was captured by the Spanish. While a prisoner in Santa Fe, his scientific records regarding the area were seized. Pike, however, hid many of his notes and from these wrote his account of his journey. Thomas Jefferson had a copy of this book in his personal library.

Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep; New York: A.H. Inskeep, 1814

First edition

F592.4 1814

“We had not gone far from this village when the fog cleared off, and we enjoyed the delightful prospect of the ocean, the object of all our labours, the reward of all our anxieties. This cheering view exhilirated the spirits of all the party, who were still more delighted on hearing the distant roar of breakers.”

Only a portion of Lewis and Clark’s accounts of their epic 1806 expedition west appeared in print. After Meriwether Lewis’ mysterious death, the task of editing their journals fell to William Clark who in turn asked Philadelphia lawyer Nicholas Biddle to complete the job. The story was finally published in February 1814. More than fourteen hundred copies were distributed. The book sold for six dollars. Lewis often wrote personal reflections of what he experienced while recording his scientific observations. His writing had a raw quality that evoked the danger and high adventure of the trip across an unknown wilderness. His report had a profound romantic effect upon the United States. However, a much more aggressive westward vision quickly outstripped President Jefferson’s modest notion of continued agrarian opportunities with a little commerce thrown in for good measure.

Coblenz: J. Hoelscher, 1839-41

First edition

E165 W64

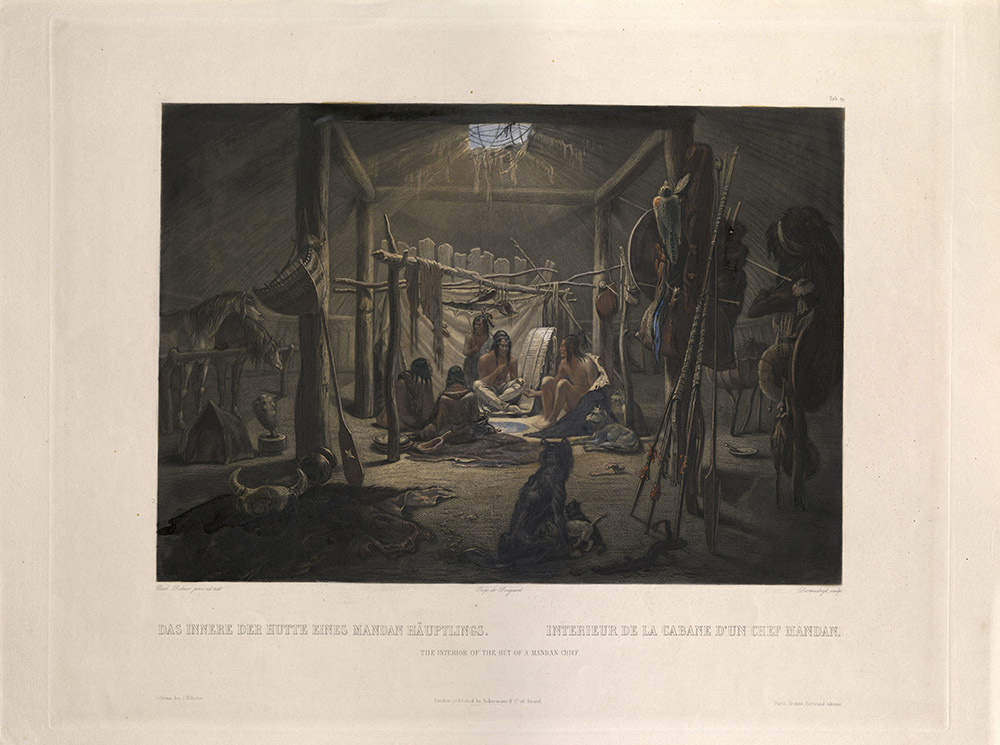

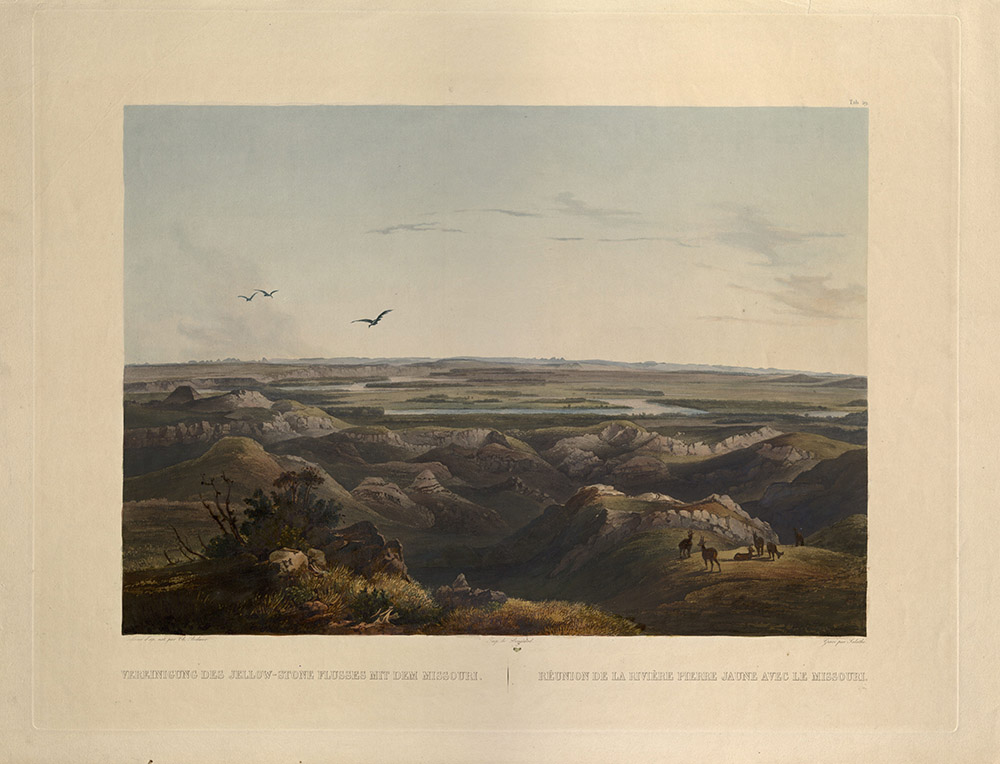

No artists accompanied Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their expedition across America. Neither President Thomas Jefferson nor Lewis thought of including one in the Corps of Discovery, a fact that Lewis lamented more than once during the journey. German naturalist Maximilian, Prince of Wied-Neuwied, traveled through North America in 1832-34 accompanied by Swiss artist Karl Bodmer. Bodmer’s landscapes and portraits of Native Americans of the upper Missouri River in present-day North Dakota and Montana are some of the earliest European depictions we have of this country and these peoples.

Herd of Bisons on the Upper Missouri

Monday, September 17, 1804 (Meriwether Lewis)

“... This scenery already rich pleasing and beautiful was still farther hightened by immence herds of Bullaloe, deer Elk and Antelopes which we saw in every direction feeding on the hills and plains. I do not think I exaggerate when I estimate the number of Buffaloe which could be compre[hend]ed at one view to amount to 3000.”

The Interior of a Hut of a Mandan Chief

Saturday, October 27, 1804 (William Clark)

“... Came too at the Village on the L.S. this village is situated on an eminence of about 50 feet above the Water in a hansom plain it contains houses in a kind of Picket work, the houses are round and verry large containing several families, as also their horses which is tied on one Side of the entrance.”

Bison Dance of the Mandan Indians

Saturday, January 5, 1805 (William Clark)

“... A Buffalow Dance for 3 nights passed in the 1st Village, a curious Custom…all this is to cause the buffalow to Come near So that they may Kill them.”

Junction of the Yellowstone and the Missouri

Thursday, April 25, 1805 (Meriwether Lewis)

“I determined to encamp on the bank of the Yellow stone river which made its appearance about 2 miles South of me. The whol face of the country was covered with herds of Buffaloe, Elk & Antelopes; deer are also abundant, but keep themselves more concealed in the woodland. The boffaloe Elk and Antelope are so gentle that we pass near them while feeding, without appearing to excite any alarm among them; and when we attract their attention, they frequently approach us more nearly to discover what we are, and in some instances pursue us a considerable distance apprenly with that view. We encamped on the bank of the yellow stone river, 2 miles South of its confluence with the Missouri.”

View of the Rocky Mountains

Sunday, May 26, 1805 (Meriwether Lewis)

“In the after part of the day I also walked out and ascended the river hills which I found sufficiently fortiegueing. On arriving to the summit [of] one of the highest points in the neighborhood I thought myself well repaid for my labour; as from this point I beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time.”

The White Castles on the Upper Missouri

Friday, May 31, 1805 (Meriwether Lewis)

"The hills and river Clifts which we passed today exhibit a most romantic appearance… the earth on the top of these Clifts is a dark rich loam… where the hills and plains on either side of the river has trickled down the soft sand clifts and worn it into a thousand grotesque figures, which with the help of a little imagination and an oblique view, at a distance are made to represent eligant ranges of lofty freestone buildings, having their parapets well stocked with statuary; collumns of various sculpture both grooved and plain, are also seen supporting long galleries in front of those buildings; in other places on a much nearer approach and with the help of less imagination we see the remains or ruins of eligant buildings; some collumns standing and almost entire with their pedestals and capitals; others retaining their pedestals but deprived by time or accident of their capitals, some lying prostrate and broken othe[r]s in the form of vast pyramids of conic structure bearing a serees of other pyramids on their tops becoming less as they ascend and finally terminating in a sharp point. Nitches and alcoves of various forms and sizes are seen at different hights as we pass. The thin stratas of hard freestone intermixed with the soft sandstone seems to have aided the water in forming this curious scenery. As we passed on it seemed as if those seens of visionary inchantment would never have and end; for here it is too that nature presents to the view of the traveler vast ranges of walls of tolerable workmanship, so perfect indeed are those walls that I should have thought that nature had attempted here to rival the human art of masonry had I not recollected that she had first began her work."

Washington: Printed by order of the United States’ Senate, 1843

F592 F875 1843

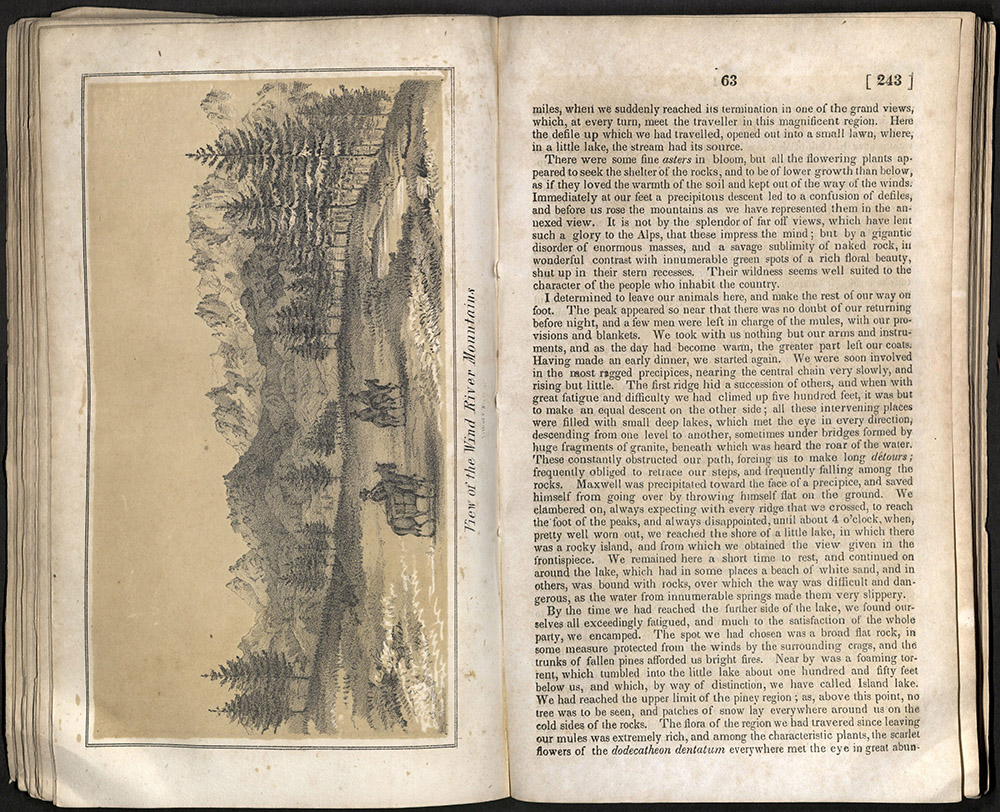

“It is not by the splendor of far off views, which have lent such a glory to the Alps, that these impress the mind; but by a gigantic disorder of enormous masses, and a savage sublimity of naked rock, in wonderful contrast with innumerable green spots of a rich floral beauty, shut up in their stern recesses. Their wildness seems well suited to the character of the people who inhabit the country.”

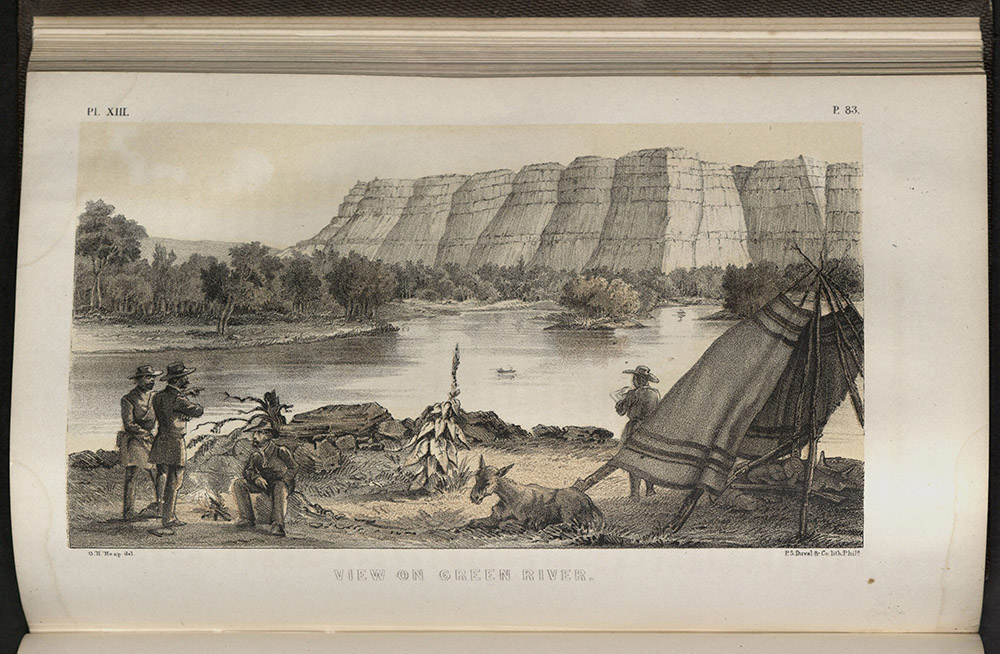

John C. Fremont’s illustrated reports to Congress were read in the United States and abroad. They provided much helpful information about overland routes. The reports also helped dispel a long-standing myth that the center of the continent was a desert. The U.S. Senate ordered the publication of ten thousand copies of Fremont’s reports. Fremont, married to Senator Thomas Hart Benton’s daughter Jessie, dictated his reports to his wife, who further developed them in a dreamy style. The adventures were read by the public as part of a political argument to settle the west.

Washington: Gales and Seaton, printers, 1845

First edition, Senate issue

F592 F874 1845

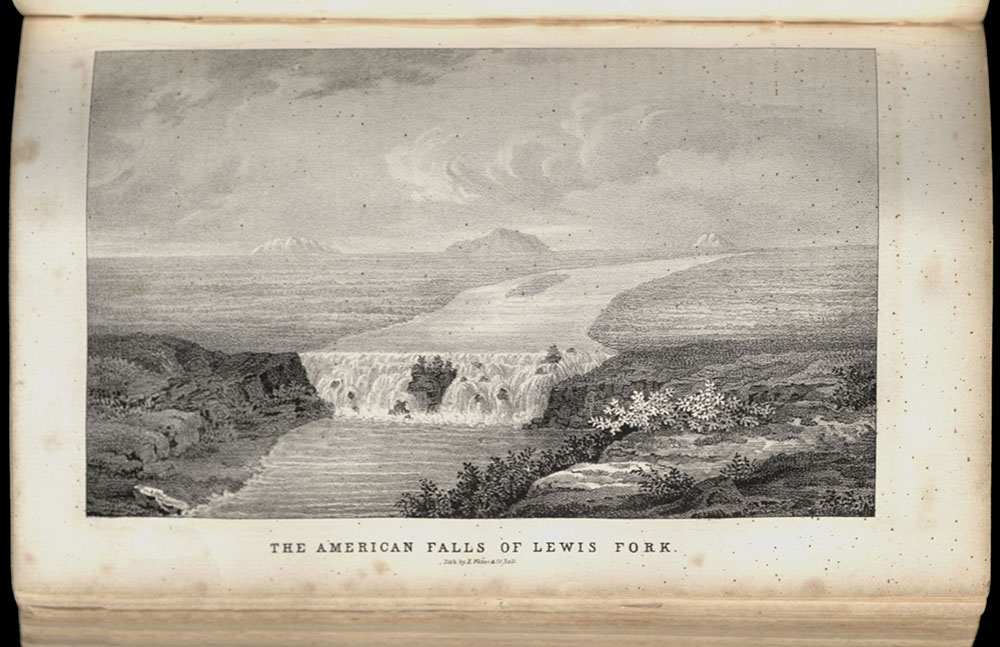

“We glided on without further interruption between very rocky and high steep mountains, which sweep along the river valley at a little distance, covered with forests of pine, and showing occasionally lofty escarpments of red rock. Nearer, the shore is bordered by steep escarped hills and huge vertical rocks, from which the waters of the mountain reach the river in a variety of beautiful falls, sometimes several hundred feet in height.”

This report documents John Charles Fremont’s two great expeditions. The first, in 1842, explored the country between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, following the Kansas and Great Platte Rivers. The second, in 1843-44, explored Oregon and Northern California. Fremont’s company traveled from the Great Salt Lake to Vancouver, then south to San Francisco, and then headed east over the California desert. In large part, Fremont’s expeditions were responsible for opening up the American West to European settlers. This edition included a large map produced by Charles Preuss. Preuss was one of the great cartographers in American history. His accurate mapping skills were of primary importance to those hoping to undertake the difficult journey west. Because this map was based on direct observation, it was more trustworthy than anything else available at that time. The year after this book was published, 1846, saw an explosion of national expansion: war over Texas with Mexico, the settlement of the dispute over ownership of the Pacific Northwest, a vast overland emigration to Oregon and California, and the Mormon flight to Utah Territory. This edition contains twenty-two lithographic plates and five maps, including the Preuss map.

Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, printer, 1848

E405.2 U56 1848

“The view from this place, is particularly beautiful; on the farther side of the Rio del Norte, a high ‘mesa’ or table land, stretches down the river; just opposite our camp it is 300 feet in height, and at the very ledge rises an ancient ruin, that from its singular position, excites the speculations of the curious.”

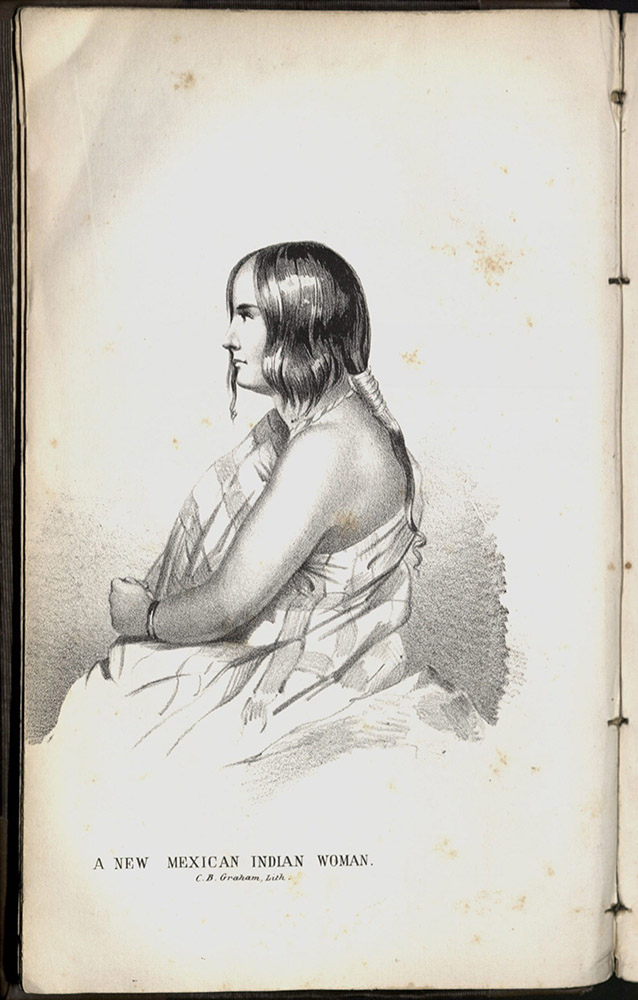

William Emory, born in Maryland, enrolled at the United States Military Academy at West Point and was graduated in 1831. In 1838, he married the great-granddaughter of Benjamin Franklin, Matilda Wilkins Bache. While in the U.S. Army, Lt. Emory became a member of the Topographical Engineers Corps. He surveyed the United States-Mexican border in 1846. Emory’s report about this tour, Notes of a Military Reconnoissance, details the military expedition from Bent’s Fort through what would become New Mexico, Arizona, and southern California. Lt. Emory kept daily entries during the march and included detailed descriptions of the terrain, trails, rivers, villages, forts, pueblos, prehistoric ruins, animals, plants, Native Americans, and Mexicans, and problems encountered by the soldiers along the way. He recorded longitude and latitude – data which would later enable him to prepare accurate maps. These notes, submitted to Congress, were published for a U. S. citizenry keenly interested in the vast expanse of the Southwest. His work is a superb study of lands newly wrested from the Mexican government and a major contribution to the geographical knowledge of North America. His descriptions of Native Americans helped influence a newly forming discipline called “anthropology.”

Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848

First edition

F864 F851848

“There was a majesty in the lofty groves which now surrounded us, and a music in the plash of the wild duck as it lit upon the bosom of the river; there was music even in the scream of the parroquette that swept over our heads; there was a charm in everything, for we now really felt that our trials were at an end.”

John Fremont’s journey through the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys mentions many of the early ranchos and Native Americans he encountered en route. Out of this journey, Fremont produced his map of Oregon and Upper California, in which he added many new place names to the geographical nomenclature of the American West, including the Humboldt River, Lake, and Range in present-day Nevada. In this work Fremont coined the phrase “El Dorado,” as an early announcement of the discovery of gold in California.

REPORT OF THE SECRETARY OF WAR, COMMUNICATING…

Washington, 1848

F801 U58 1848

“Quantities of fine large clingstone peaches were spread out on the ground, as the owners were dividing the loads, so as to carry them up the ladders. And whenever we approached, they would cry out to us, ‘coma! coma!’ – ‘eat! eat!’ and point to the peaches. They generally wear the Navajoe blanket, marked with broad stripes, alternately black and white. Their pantaloons are very wide and bag-like, but are confined at the knee by long woollen stockings, and sometimes buckskin leggings and moccasins. The women stuff their leggings with wool, which makes their ancles look like the legs of an elephant.”

This report was written by J.W. Abert, a lieutenant in the Topographical Corps. Abert was born in 1820 in New Jersey. He was the son of the Chief of the Bureau of Topographical Engineers. In 1838, he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point. He joined the Topographical Corps in 1843. In 1845, he was attached to the third expedition of John Charles Fremont, who had been assigned to reconnoiter south and east along the Canadian River through Kiowa and Comanche territory. Instead, Fremont took his party to California, giving command of the assignment to Abert. The company was made up of one other officer and the rest civilians. Abert followed the Canadian into New Mexico and then Texas, eventually following the Red River, crossing the present Oklahoma boundary along the way. Abert produced the most accurate-to-date maps of the region, helping later explorers find campsites and water. He gave in-depth descriptions of the habits and customs of the Kiowa and Comanche. Abert returned to New Mexico in 1846, where he continued his studies in natural history. He visited each of the Rio Grande pueblos.

CENTRAL ROUTE TO THE PACIFIC, FROM THE VALLEY OF…

Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and Co., 1854

First edition

F593 H43

“This camp was to us a scene of real enjoyment; a long and tedious march, over planes of unvarying sameness, was over, and we were now on the eve of entering upon a new and unexplored country, which promised to the admirers of nature a rich and ever-varying treat.”

Senator Thomas Hart Benton was determined to have a transcontinental railroad constructed from St. Louis as directly west as possible to the Pacific Ocean, the great Rocky Mountain barrier notwithstanding. In 1853, three parties set out to find and publicize the most practical and central route west. The first of these parties to begin their expedition was led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in California. Beale, a friend of John Fremont and the legendary Kit Carson, had made six previous crossings. Beale chose his cousin, Gwinn Harris Heap to travel with him from Westport, Missouri westward under a Congressional mandate to select lands suitable for Indian reservations. It was Heap who kept the journal of the crossing. The expedition reached Los Angeles following a route through New Mexico and Utah. This narrative of the journey contains picturesque descriptions of many previously unexplored areas and includes an account of Rev. James W. Brier, a pioneer emigrant who had crossed Death Valley in 1849. This is the earliest published account of Death Valley. Heap noted the usefulness of camels for desert expeditions and was later commanded to take twenty-five with him, the so-called “Camel Corps,” in an 1857 expedition to California.

REPORT UPON THE COLORADO RIVER OF THE WEST…

Washington: Govt. Print. Off, 1861

First edition, Senate issue

F788 U58 1861

“The regular slopes gradually gave place to rough and confused masses of rock, and the scenery at every instant became wilder and more romantic. New and surprising effects of coloring added to the beauty of the vista. In the foreground, light and delicate tints predominated, and broad surfaces of lilac, pearl color, pink, and white, contrasted strongly with the somber masses piled up behind. In their very midst a single pile of a vivid blood red rose in isolated prominence.”

Joseph Ives was commissioned to explore the possibilities of navigation of the Colorado River as a supply route to settlements in the region. Ives described the Grand Canyon as “altogether valueless. Ours has been the first and will undoubtedly be the last, party of whites to visit…It seems intended by nature that the Colorado River along…its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.” Most of the illustrations for the report are credited to Heinrich Balduin Mollhausen (1825-1905), a German who had made two previous trips across the American West. Full-page lithographs in color, five full-page steel engravings, sixty-nine woodcuts, and other illustrations make up this the first pictorial record of the Grand Canyon.

Jacksonville: Oregon Sentinel Printing Office, 1865

First edition

F881 U54

“The time occupied in making the trip from Boise to Fort Klamath, was thirty-four days. The number of days on which we traveled was twenty-three, which is about the time required to pass either way over the route, now that it is explored and marked.”

This report originally appeared serially in the pages of the Oregon Sentinel. It was then reprinted in pamphlet form from the same type. Charles S. Drew wrote the report as an aid to military operations against Indians. The expedition was made through country that, in part, had been unexplored, making this the first published account of the area. Drew, an Army officer, wrote the report with some sympathy for Indians living in Idaho. The Oregon Sentinel printed the account, not as a military guide, but as a guide to a new route to Idaho mines from southern Oregon and California. University of Utah copy is in original printed yellow wrappers; front wrapper is inscribed to “Pinkney Pickens, Esq. compliments of C.S. Drew.” Missing lines on page fifteen are supplied in the author's hand.

Washington: G.P.O., 1875

First edition

F788 S65 1875

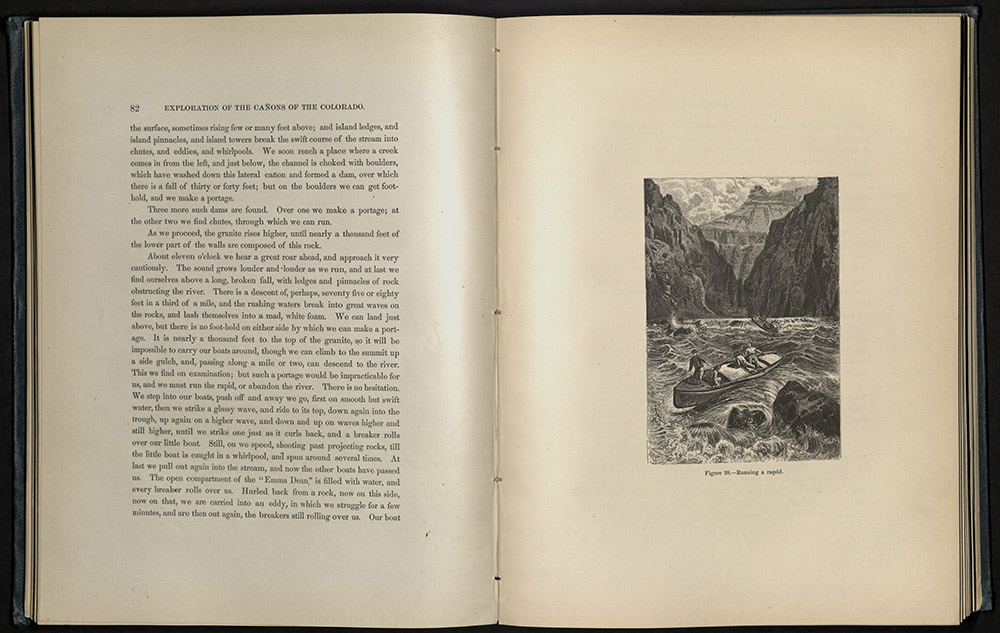

“And now we go on through this solemn, mysterious way. The river is very deep, the canon very narrow, and still obstructed, so that there is no steady flow of the stream; but the waters wheel, and roll, and boil, and we are scarcely able to determine where we can go…We can neither land nor run as we please.”

John Wesley Powell, director of the U.S. Geological Survey, leading a team accompanied by artists and photographers, produced an extensive scientific report that underscored the dramatic features and economic possibilities of the American West. Powell’s report on his series of explorations included two large maps and eighty wood engravings of the landscape of the Grand Canyon. The report began with a description of trips down the Green and Colorado Rivers, beginning on May 24th, 1869. Powell and a party of ten men embarked in four boats at Green River City, Wyoming and headed south towards the mostly unexplored Colorado River. In late August, after enduring harrowing rapids and several near-fatal accidents, as well as being perilously low on supplies, the explorers emerged from the Grand Canyon at Callville. This trip was the foundation for other expeditions led by Powell, during which he discovered the last unknown river (the Escalante) and the last unknown mountain range (the Henry Mountains) in the United States. Powell’s deep appreciation for the American West makes his report one of the most celebrated works in the literature of exploration. He was the first government scientist to understand fully the climatic challenges of the West. His pioneering scientific and natural history gave way to an early debate about the viability of settling the country. Powell was apparently reluctant to write this book. It was only after the House of Representatives refused to consider his request for funding of future explorations that Powell agreed to publish a history of his first expedition. The book became one of the best and most popular adventure narratives in American literature. Powell’s potent prose and the book’s illustrations brought the drama of the remote and demanding Western landscape into the parlors of an awed and eager Eastern audience.

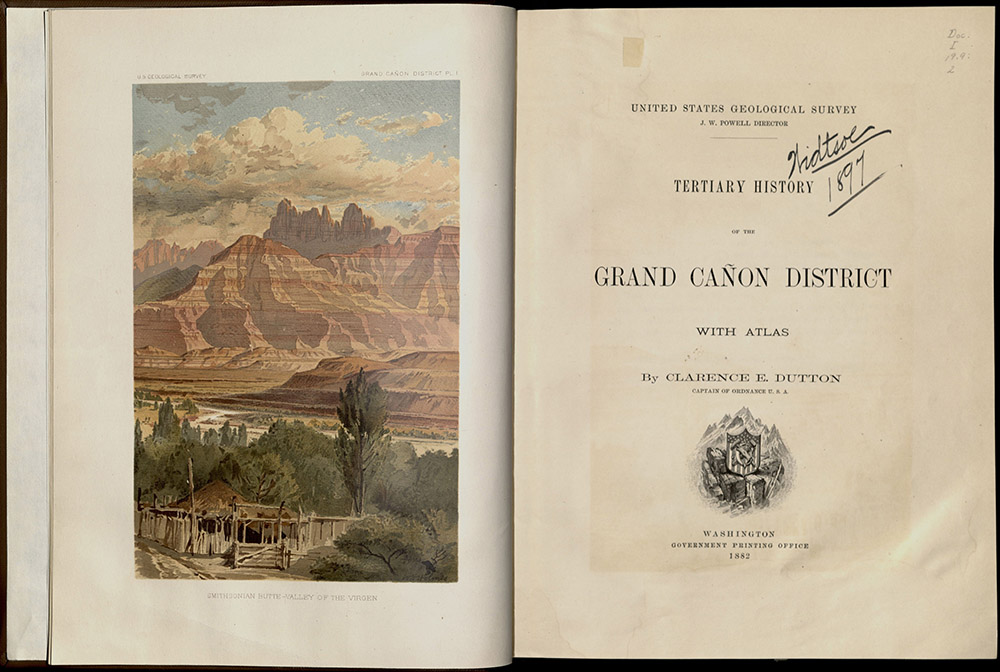

TERTIARY HISTORY OF THE GRAND CAŃON DISTRICT…

Washington: GPO, 1882

First edition

QE691 D86 1882

“This name has been repeatedly infringed for purposes of advertisement. The cańon of the Yellowstone has been called ‘The Grand Cańon.’ A more flagrant piracy is the naming of the gorge of the Arkansas River in Colorado ‘The Grand Cańon of Colorado,’ and many persons who have visited it have been persuaded that they have seen the great chasm. These river valleys are certainly very pleasing and picturesque, but there is no more comparison between them and the mighty chasm of the Colorado River that there is between the Alleghenies or Trosachs and the Himalayas.”

Clarence Dutton explored the Grand Canyon in the early 1880s. His report provided an extensive study of the region. An atlas volume contained some of the earliest illustrations of the Grand Canyon, including twelve double-sheet maps (most of which are printed in color) and ten double-sheet panoramas (most tinted). One of the panoramas is by Thomas Moran, who later became a well-known painter of the American West landscape. The other panoramas were drawn by archaeologist William Henry Holmes. The text volume contains forty-two additional plates, including nine by Moran and twenty by Holmes. Three of these are in color, four are photographs.

Emigrants

Between 1840 and 1860 nearly three hundred thousand people traveled westward on overland trails. The reasons for this migration varied – some sought quick wealth in the Gold Rush, some looked for better agricultural lands, some believed that the west would improve their health. The Mormons looked for a refuge from religious persecution. Whatever the reason, emigrants believed that they could improve their lives by moving West. Migrants depended upon reliable information to get them to their remote destinations. Tragic stories of lonely souls buried somewhere in the unforgiving wilderness were rampant. Trail guides outlined the best routes, listed what to bring, and forewarned of menace. Many of these guides were derived from personal accounts. Others were nationally published guides compiled from newspaper accounts and government surveys. Few original trail guides survive because of heavy use. Or perhaps they were thrown away in frustration.

After the Civil War, the transcontinental railroads eliminated the need for trail guides. The demand became one for practical information about the destinations themselves. In the late 1860s governmental agencies and railroad companies issued hundreds of sophisticated (and often exaggerated) pamphlets promoting the virtues of western lands.

“The many overwrought and highly coloured pictures which have been drawn of different parts, of what is in common language called the Western Country, have produced more evil and injury than can be easily conceived. That those regions do present flattering views to the emigrant, there is no doubt; but there is no country, where labour is not indispensably necessary, and where the common routine of acquiring gain, is not slow and gradual.”

Although this emigrant guide emphasized relatively settled areas around the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, it also contained information about trans-Mississippi country, based, in part, on previous accounts. William Darby served under General Jackson in Louisiana as surveyor for the area. His knowledge of geography came from personal explorations in Texas, Louisiana, and the border with Canada. Because of these explorations, he was able to help in the delineation of both the northern and southern boundaries of the United States. This edition includes a large colored map of the United States with Louisiana and a smaller map depicting Mobile, Perdido, and Pensacola bays.

“There is, we suppose, no portion of North America, East of that great dividing chain – the Rocky Mountains – similar to that on the West. The general features of the country, the climate, the soil, vegetation, all are different. Nature appears to have created there, upon a grander scale. The mountains are vast; the rivers are majestic; the vegetation is of a giant kind; the climate, in the same latitude is milder.”

One of the most important early narratives of travel in the American West, Overton Johnson gave an excellent account of his company’s adventures with the Indians, their customs, dances, and methods of warfare. He described the trail the company followed to California in vivid detail. The appendix included complete instructions to emigrants with regard to supplies, equipment, an itinerary, and notes on various stopping places along the way.

“Recollect that you are a component part of the country. Take no steps that will not reflect honor, not only upon yourself but your country. Oppose all violations of order, and just law – Unite with the well disposed to sustain the rights of individuals whenever encroached upon…Let schools, churches, beneficial societies, courts, &c., be established forthwith. Make provision for the forthcoming millions that shortly shall people your ample valleys, and golden hills…”

The California gold rush was one of the biggest news stories of the nineteenth century. The demand for information about California and how to get there was insatiable. Between 1848 and 1853, material on the overland trails flowed from printing presses like the proverbial gold from the hills. The author of this guide, Joseph Ware, never made the overland trip himself, but compiled information from various contemporary published sources, including the reports of John C. Fremont.

Milwaukee: Daily Sentinel Steam Power Press, pub. by C. Child, 1852

F593 C5

“I will premise with the hint that the trip across the plains and mountains, is one of toil and hardships, and, with the best outfit, it would be a difficult matter indeed to metamorphose it into a pleasant journey…”

Andrew Child traveled to California in 1850 and sent a copy of his journal home to Wisconsin from Nevada City in December of that year. Two years later, the journal was published as a guide.

San Francisco: Whitton, Towne & Co., 1858

First edition

F593 W34

“There are those who speak of making the passage of the plains a pleasure trip, from beginning to end. Don’t believe a word of it…When you hear men speaking of it, only as a pleasure trip, depend upon it that either they know nothing about it, or are ardent and enthusiastic admirers of nature, and therefore see at almost every step, something new, strange, or magnificent to admire, that affords them pleasure…Still, as a whole, the journey of the plains is one of peculiar and almost unequaled interest, and more than compensates the observant traveler ten fold for all his fatigue and privation.”

William Wadsworth made several trips across the plains. His book was considered one of the most useful of the overland guides available beginning in the 1840s. He based his writings on his own observations and experiences and included information from other sources.

MEMORANDA OF A JOURNEY ACROSS THE PLAINS FROM…

Olympia: Printed at the office of the Washington Standard, 1863

F594 H48

“To-day we crossed the summit of the Rocky Mountains, the back-bone of our country, the dividing ridge between the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific. We paused not to consider as did Caesar of old, nor await the casting of the die; but moved on with that ease and dignity becoming persons in our condition.”

This copy of Journey Across the Plains was given by Randall Hewitt to his sister, Cynthia E. Hewitt, a school teacher and pioneer of Washington Territory. University of Utah copy donated by Emily-Ellen Hewitt, granddaughter of the author.

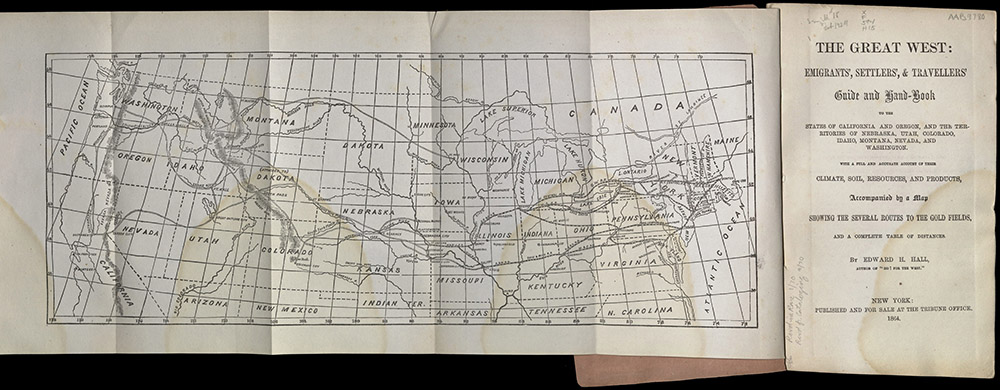

New York: Tribune Office, 1864

First edition

F594 H15

“Have a good reason for breaking the old moorings before looking for better ones; and when you start on a long trip to the far West, do not cherish the idea too often entertained, that it is to be but a holiday excursion, soon to be over, when you will tumble into some rich gulch or placer, only to come forth laden with stores of gold…To succeed in any new field of labor, great industry and perseverance are required, and the emigrant to the Great West will secure his fortune only through the continued exercise of these virtues.”

In another cut-and-paste compilation of various sources on the journey west, English emigrant Edward Hall used, among other things, newspaper articles published in the New York Tribune to put together his emigrant guide. Later in 1864, Hall published yet another trail guide, this time with tables of distances, summaries of homestead laws and tips for making the crossing more comfortable.

“The citizens of the Territory, are generally an intelligent people, and all that is lacking to make comfort dwell in the shadow of each household, is an increase of population, and especially the introduction of female society in greater abundance.”

Asa Mercer published his first work when he was twenty-five, as he was arranging for a second emigration party to the Pacific coast. He said later that copies of this work were distributed for free. Mercer encouraged young women to immigrate to Washington Territory. He was so successful in this recruitment that these women were known for years as “Mercer Girls.” Mercer served two sessions as the first president of Washington Territorial University. From Washington he moved to Oregon and then finally to Texas. In 1883 he created a literary sensation with his western novel, The Banditti of the Plains. With Washington Territory, Mercer gave a minute account of the territorial boundaries and described the geographical, topographical and sociological features of the region west of the Cascades including climate, agricultural resources, lumber, minerals, fish and fishing, whaling, grazing lands, manufacturing, the markets and trade, Indians, newspapers, schools, and towns. This is the first detailed account of the area after its establishment as a territory, with an appendix of elaborate tables of routes and distances to various mining regions of Idaho and Montana.

Adventurers

Clearfield, Pa: D. W. Moore, 1839

First edition

F592 L36 1839

“These prairies were completely covered with fine low grass, and decorated with beautiful flowers of various colors; and some of them are so extensive and clear of timber and brush that the eye might search in vain for an object to rest upon. I have seen beautiful and enchanting sceneries depicted by the artist, but never any thing to equal the work of rude nature in those prairies.”

Zenas Leonard's memoirs of his travels were written, he said, at the request of friends. In order to avoid having to repeat his story over and over again, he decided to write his Narrative. It was published by a small press in his home town. Leonard left St. Louis on April 24, 1831, heading west to make his fortune trapping for furs and trading with Indians. He described in detail the manners and customs of the Indian tribes with whom he traded while crossing the Rockies. The trip was plagued with misfortune. Leonard was attacked by a grizzly bear, encountered hostile Blackfoot Indians, and nearly starved to death. Nothing was heard of him for five years, until he finally reached the Pacific coast, just south of San Francisco. He didn’t make his fortune, but his Narrative is one of the most honest and compelling accounts of early transcontinental treks.

“And yet stern and wild associations gave a singular interest to the view; for here each man lives by the strength of his arm and the valor of his heart. Here society is reduced to its original elements, the whole fabric of art and conventionality is struck rudely to pieces, and men find themselves suddenly brought back to the wants and resources of their original nature.”

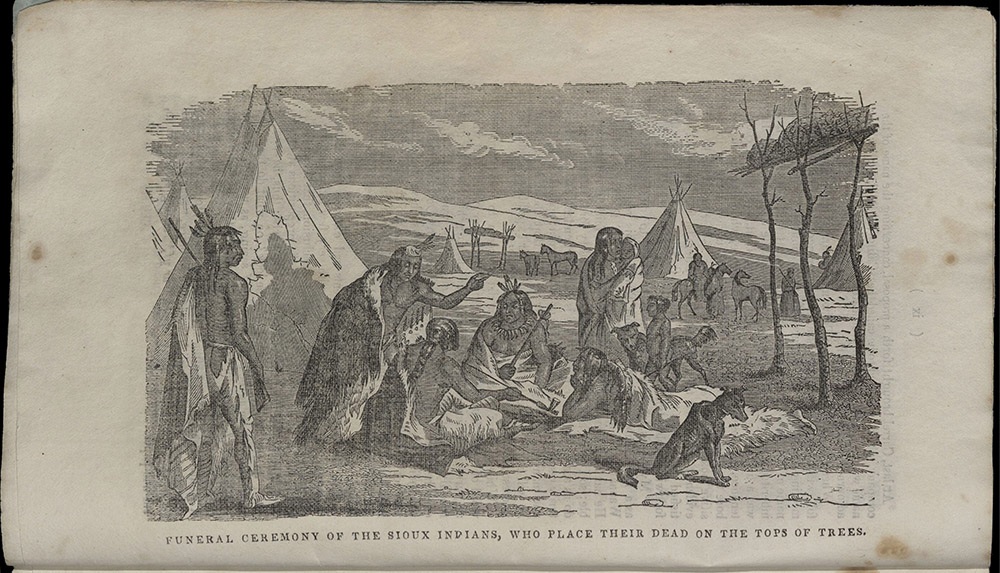

Francis Parkman undertook his journey to Oregon in an attempt to restore his health, but he was also interested in learning about Native American life and gathering information for a history of the conflict between the French and British in North America. Traveling along the Oregon Trail and then south following the eastern edge of the Rockies, Parkman returned on the Santa Fe Trail. Along the way he lived with a band of Sioux and met with legendary frontiersmen like Jim Beckwourth. He arrived home in poor health and dictated this work to his cousin. The account is part history, part travel narrative, part adventure story. It appeared first as a series in the Knickerbocker (1847-1849). It became a best seller and remains one of the great literary and historical narratives of the American experience. Parkman went on to become a noted historian, admired for his superior writing and his careful research. University of Utah copy 2 has handwritten shelfmark, “No. 2107 Utah Library Salt Lake City Utah Ty” (Territory) and University of Deseret stamp.

St. Louis, Barclay, 1850

First edition

F593 A19 1850

“Up to Leavenworth we might still consider ourselves within the limits of civilization, but beyond that place commenced the real wilderness of the Great West, inhabited only by savages and wild animals.”

Swiss artist Karl Bodmer’s etchings from an expedition made in the 1830s up the Missouri River were used to illustrate Dreadful Sufferings. Bodmer’s realistic images of the Plains Indian tribes were the original source for later distorted depictions of the American Indian in the nineteenth century popular press. The illustrations in Dreadful Sufferings are dramatic representations of how Bodmer’s etchings were reproduced, modified, and reinterpreted to fit into contemporary perceptions. Here, the image of the “noble savage” changed to images of sensational scenes of horror and fear, images that helped justify some of the more brutal policies of Manifest Destiny.

London: William Shoberl, 1850

First edition

F865 R96

“There is no career, however humble, which drags its slow length along unmarked by some eventful epoch, whether of joy or grief – some passage in the monotonous routine of an obscure existence, which serves to indicate the long, dull stages of our journey to the grave – some decisive moment, in short, when the mind, abandoning itself to extremes, rashly compromises the future in the exaggerations of a heated imagination, and embraces at a grasp its chances of good or evil.”

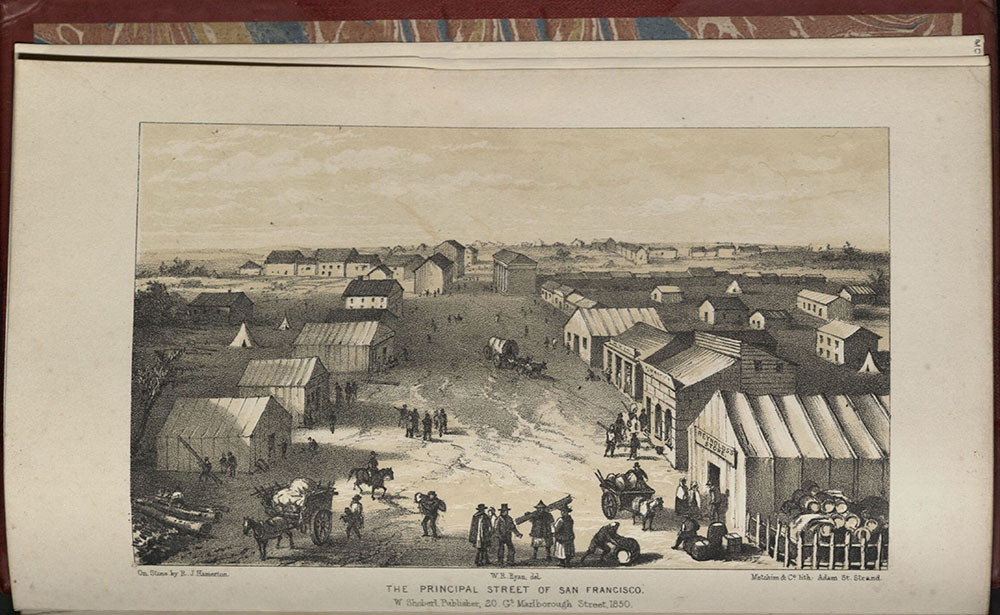

Englishman William Ryan had a great adventure in California. He wrote in an easy style reflecting his bohemian fancy and evoking a world of prospectors, Indians, Spaniards, boom towns, breathtaking landscapes and a unique crop of men staking their all on illusive metal. Ryan prospected for nearly eighteen months on the Stanislaus River, but never struck gold. Illustrated with wood engravings and duotone lithographs.

A TRIP ACROSS THE PLAINS, AND LIFE IN CALIFORNIA…

Massillon, OH: White’s Press, 1851

F593 K28

“The stillness of death reigns over this vast plain, -- not the rustling of a leaf or the hum of an insect, to break in on the eternal solitude. Man alone dares to break it.”

This book is one of the rarest of overland narratives. Few copies were distributed because of a fire in the town where the book was published. George Keller left St. Joseph, Missouri on 20 April 1850 and reached California on 14 July of that same year. Keller chronicled the daily events along his “arduous way,” with observations on landscape, animals, Indians, and forts. The company Keller was with had a copy of Joseph Ware’s Guide, but Keller was not impressed with its accuracy. He appended his story with an overland guide of his own, giving detailed descriptions of distances and where to find wood, water, and good camps.

A RIDE OVER THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS TO OREGON AND…

London: Richard Bentley, 1852

First edition

F593 C67

“I should imagine no people were ever more disgusted with a sea voyage than we, when at the end of the seventh week the land appeared to finish it. How beautiful the islands looked as we steered between them, with a fair wind, and studding sails set on both sides. I thought the tropics more charming than ever. The water looked bluer; the palm-trees taller; the vegetation greener; and Nature seemed to receive us with open arms. She seemed to say, here I am, happy and beautiful as ever; enjoy me to the extent of your will.”

Henry Coke left St. Louis in May 1850. From there he followed the Platte to the Sweetwater, crossed over the South Pass, reaching the Dalles in Oregon in October. He then sailed to Hawaii, and returned to the United States via San Francisco. A perilous journey in 1850, seven of the young English sportsman’s companions perished. The last chapter of this book features California and the Gold Rush. Coke visited Marysville, where he met Captain Sutter, and observed the mining operation.

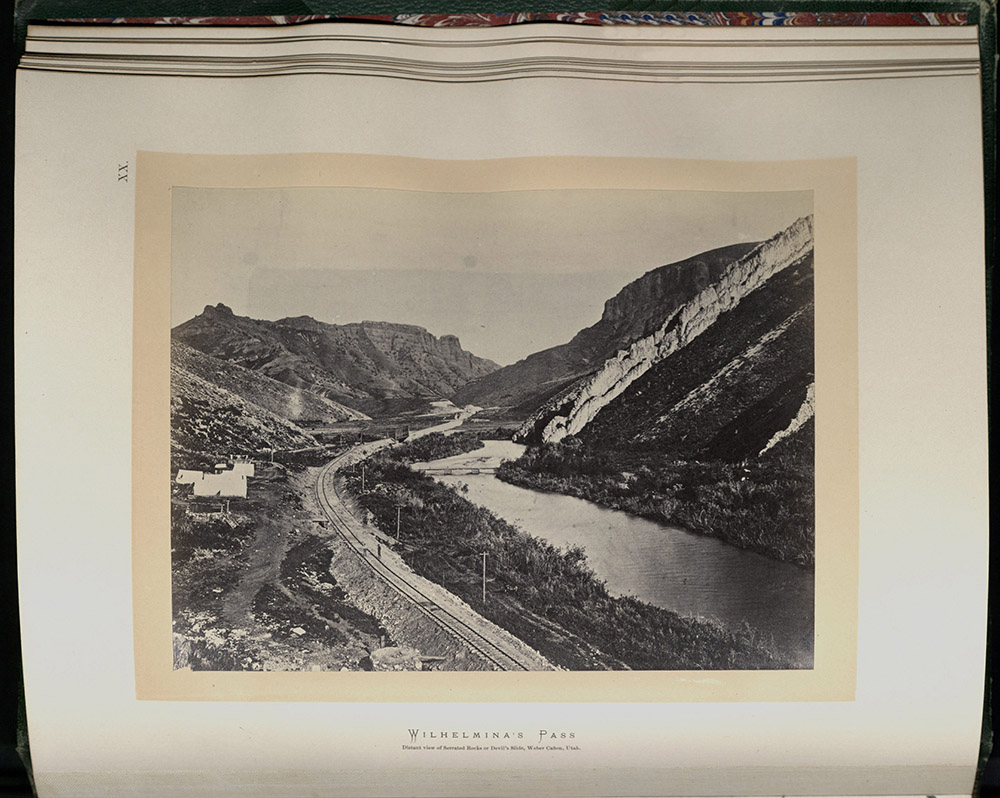

Liverpool: F.D. Richards; London: E.C. Brand, etc. 1854-1855

E166 P65

“And now our journey, so full of interest and novelty to me, was nearly completed, and we were about to exchange the rude, but bracing and healthful, prairie life for the comforts and refinements of the city…I could see that the streets were broad, and hear the refreshing sound of water rippling and gushing by the road side. Occasionally a tall house would loom up through the gloom, and every now and then the cheerful lights came twinkling through the cottage windows – slight things to write about, but yet noticed with pleasure by one fresh from the Plains.”

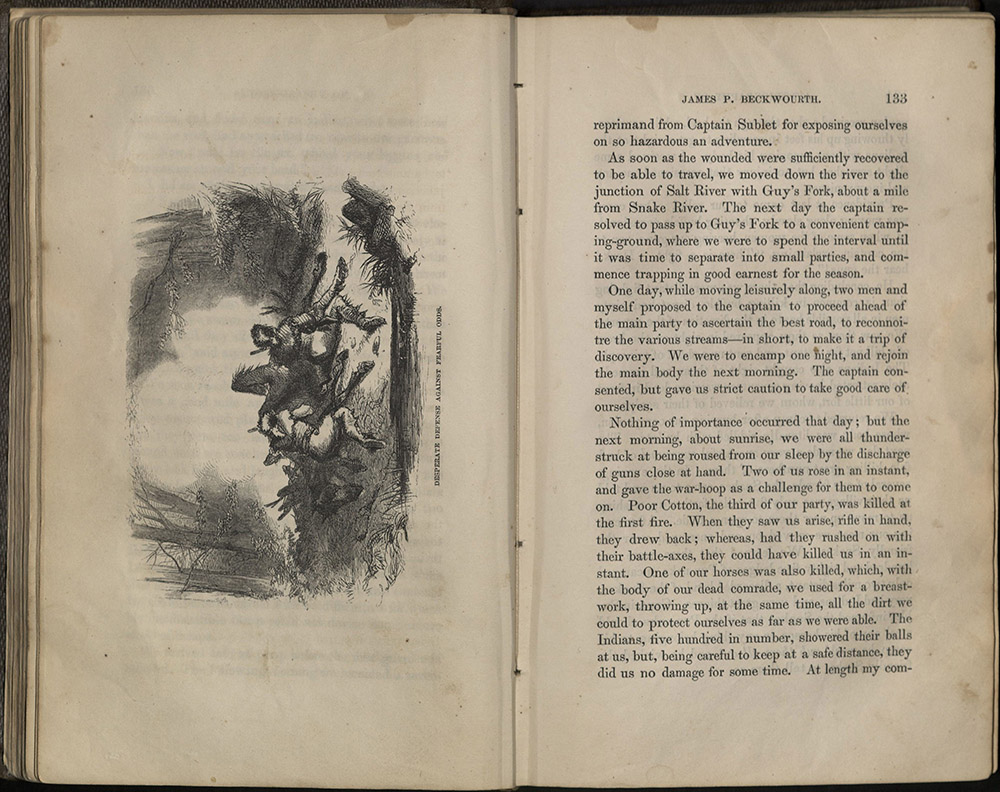

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1856

First edition

F592 B39

“The ambitious emigrant and his proud family, with their highly-raised expectations of the future that is before them: the father, so confident and important, who deems the Eastern States unworthy of his abilities…can alone find a sufficiently ample field in the growing republic on the Pacific side…”

James Beckwourth, an African-American, recorded his life story as an unceasing westward adventure of hunting, Indian fighting, and horse thievery. He dictated his autobiography to Thomas D. Bonner, would-be journalist, former temperance crusader, and itinerant Justice of the Peace in the gold fields of California. Both Beckwourth and Bonner were dedicated drinkers, a trait that heavily influenced the sensational style of Beckwourth’s story. Fantastic scenes of slain enemies, smitten Indian maidens, bloody battles, and close calls confirmed in print his already widespread reputation as a master teller-of-tall-tales. Beckwourth’s tendency to exaggerate made his autobiography something of a joke among those who knew him. Still, his adventures sold well. An English edition was also published in 1856, and a French translation was published in 1860.

Tourists

Many Americans longed to see the West, even if they didn’t want to settle there. After the fractious and devastating Civil War, the West became symbolic of a re-born nation’s grandeur. It also became a premier destination for leisure-class travelers. The railroads spent large sums on advertising and promotional packages, promising sunshine and spectacular scenery to national and international armchair adventurers. Due, in part, to the astonishing hyperbole of these promotional materials, there began a near compulsion to see the West – a place that, in the space of less than one hundred years, had become mythic and hallowed, a restorer of the soul – full of meaning that, at least for a while, could be found nowhere else.

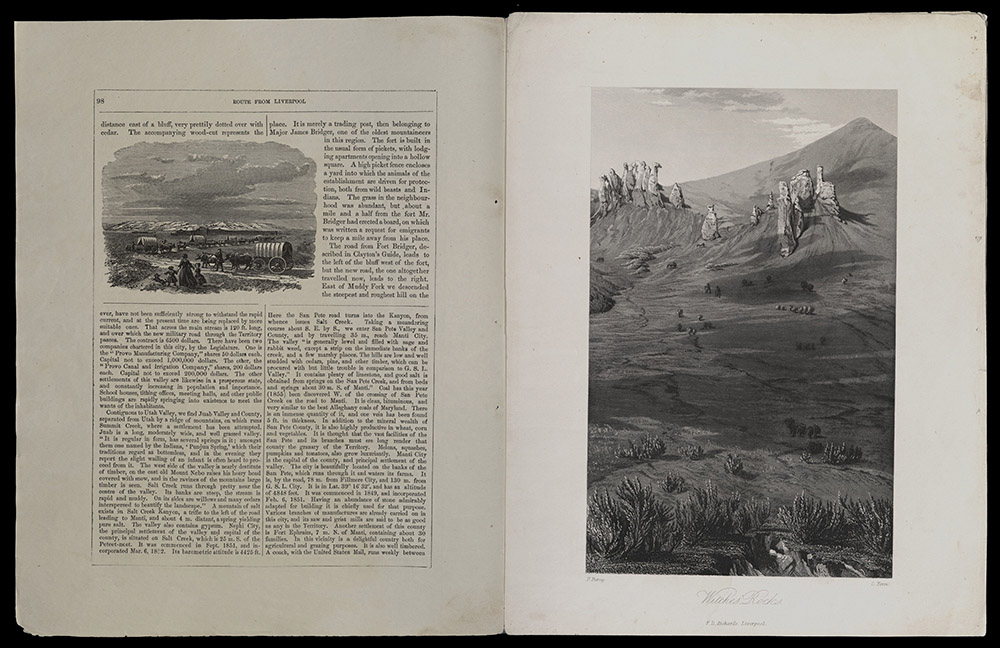

Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1851

First edition

E158 W55 1851

“This extraordinary rock was named by a party of Americans, who chanced to pass that way one Fourth of July, whence they proceeded to celebrate the great events of that period, by a succession of revellings, festivities, and hilarities, which having been concluded, they all inscribed their names, together with the word “Independence,” upon the most conspicuous portion of the rock: hence the name and notoriety, which are as firmly established, by the act, as that rock of ages itself.”

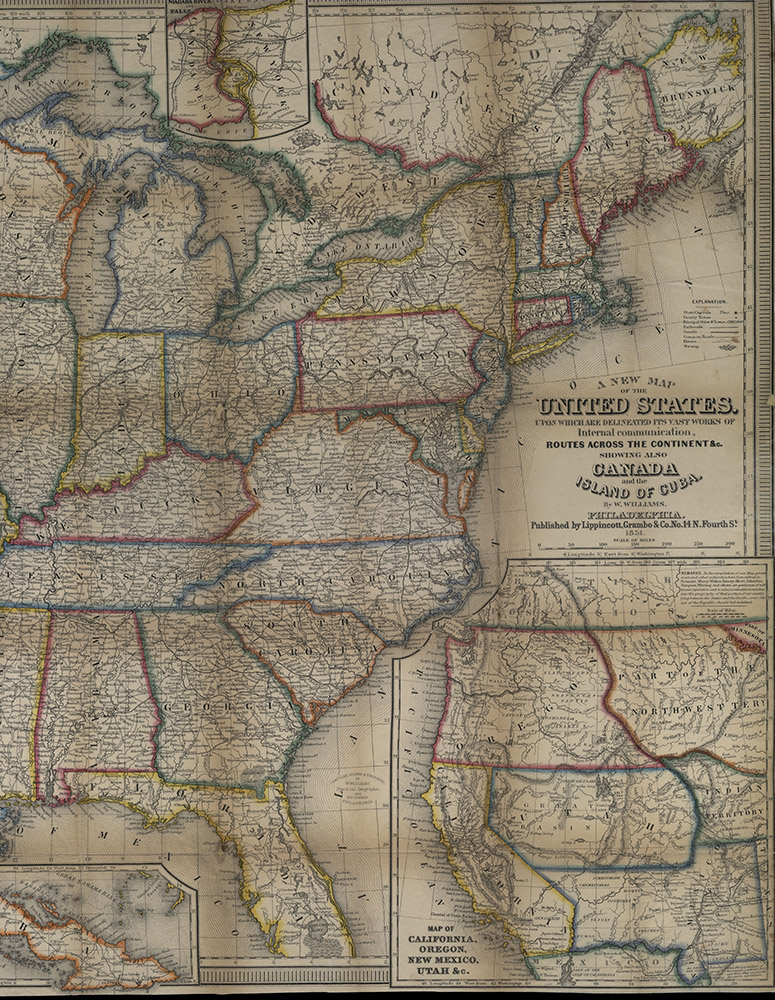

Wellington Williams was one of the most prolific travel guide writers in the United States in the 1850s. He prepared most of the guide books issued by Appleton’s from 1847 and 1854. In 1851 he began this guide book under his own name and issued it annually, with numerous changes and additions, until 1859. Included in this edition is a large folding map which extends west to include most of Texas, and small inset maps of Cuba, Havana, and Niagara Falls. There is also an inset which shows the trans-Mississippi West. Boundaries are shown according to the Compromise of 1850.

“Never in the history of our country has the term ‘The Great West’ possessed so much significance as at the present time. Thirty years ago, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois were called the far Western States, while but little was known of the vast regions beyond; now farms and villages with sites of future cities are dotted over the plains and mountain slopes as they stretch westward toward the setting sun.”

After the Civil War, the federal government renewed its interest in the western territories. Ferdinand V. Hayden led several ambitious geographic and geologic survey teams for the government into the Northern Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. Hayden promoted the American West, his surveys and himself with publications such as this. The dramatic photographs and drawings Hayden brought back to Washington helped to persuade legislators to create Yellowstone National Park. Armchair travelers enjoyed privately published extracts of his government reports.

Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., September, 1888

TF668 N67 1888

“But, in this remarkable territory, Nature dispenses her bounty with so generous a hand that, were its scenic attractions entirely obliterated, its vast and varied wealth producing capabilities would still secure for it it’s well-earned title of ‘The Wonderland of the World.’”

This pamphlet opens to a black and white detailed map showing the lines of the Northern Pacific Railroad in heavy red, its connections on the west coast in heavy black, and includes an inset of the Northeast. It is backed with sixteen panels, printed in brown, with four panels of time tables, six panels describing the country traversed, with small pastel sketches, rates, news of excursions to the North Pacific Coast, California, Montana, Eastern Washington, Alaska & Yellowstone. The colorful cover has a sporting theme and a chef preparing fresh catch.

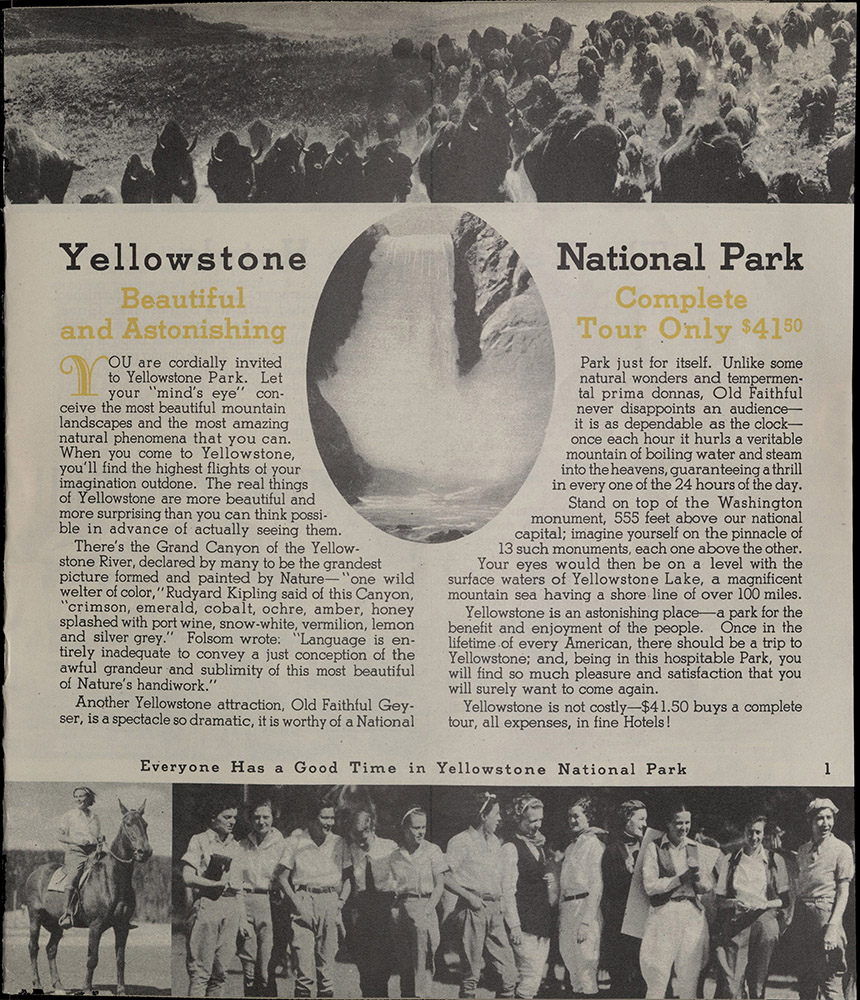

YELLOWSTONE

Yellowstone Park, WY: Yellowstone Park Hotel Company…, 1936

F722 Y24 1936

“Everyone has a good time in Yellowstone National Park.” Illustrated with photographs, this brochure included brief tour descriptions and general information about visiting Yellowstone National Park. The standard three and a half day tour cost in 1936 was $41.50.