Evolution of Darwin

"...from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been and are being evolved."

Checklist for "The Evolution of Darwin"

Curated by Luise Poulton, 2009

Exhibition poster designed by David Wolske, 2009

Digital exhibition produced by Alison Elbrader, 2011

Format updated by Lyuba Basin, 2020

The significance of his observations during his voyage on the HMS Beagle led Charles Darwin to spend the next twenty years working out a mechanism of evolution through processes of natural selection. He published his seminal work, On the Origin of Species, in 1859. The book caused a sensation when it was published. Darwin's ideas are still condemned, supported and debated one hundred and fifty years later. The work of others before him and that of contemporary scientists influenced Darwin's thinking. An evolution of thought brought Darwin to his revolutionary conclusions.

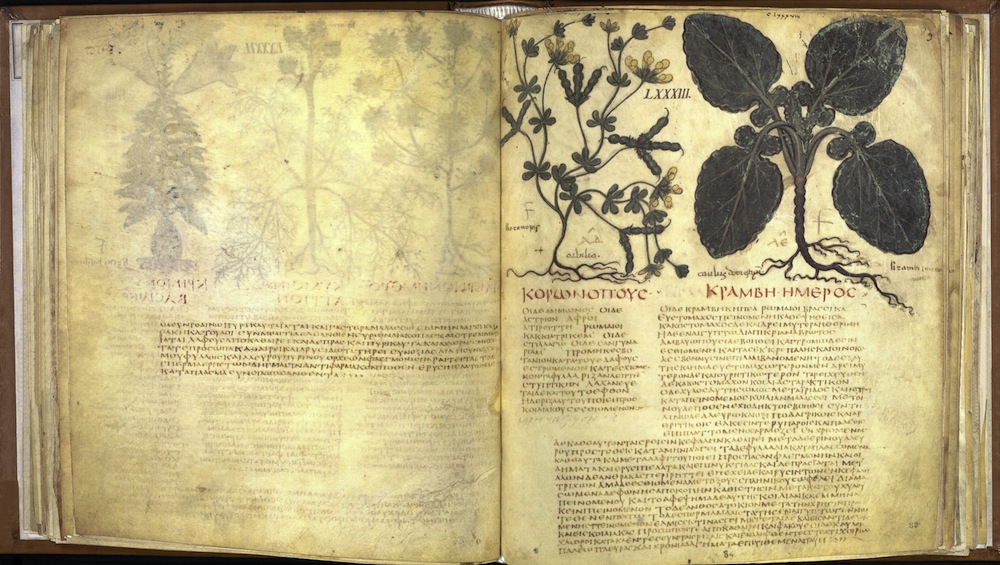

DES PEDANIOS DIOSKURIDES

R126 D56 1988

Facsimile. Ca. seventh century, Italy? This manuscript is one of the oldest in the tradition of Materia medica, a pharmacological treatise written by Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides in the first century. Dioscorides’ work was used by the medieval world for centuries. In the sixth century it was translated into Latin. By the ninth century it had been translated into Arabic, Syrian and Hebrew. More than four hundred plants are described in this illustrated herbal, each illustration outlined in red ink. The binding of wooden covers and leather replicates the character of the contemporary binding.

First printed in Venice in 1469, this is an uncritical account of medicine and natural history – in effect, an encyclopedia of science. This edition came from the press of Johannes Froben (1460-1527), a German printer who established himself at Basel. Froben became famous for printing scholarly texts, in part because Erasmus edited many of Froben’s publications. Froben also employed the as yet unknown Hans Holbein as a designer. University of Utah contemporary binding pastedowns are manuscript leaves.

Basileae: In officina Isingriniana, 1542

First edition

QK41 F7 1542

During the Middle Ages and European Renaissance, medical treatments were based on botany, but the herbals and other books available to practitioners often inaccurately identified plants. This herbal, The History of Plants, established a new standard of scientific observation and accurate illustration. Leonhart Fuchs compiled his text from various classical sources but added his own field observations. The remarkably detailed woodcuts, drawn by Heinrich Fullmaurer and Albrecht Meyer and cut by Veit Rudolf Speckle represent the first published illustrations of American plants, including the pumpkin, the marigold, maize, and tobacco – all native to Mexico and introduced into Europe as a consequence of the Columbian Encounter. The plants were identified in Latin, Greek, and German. Leonhart Fuchs was a child genius, matriculating at Erfurt University at the age of twelve. He went on to take a degree in medicine at Ingolstadt. His medical work during an outbreak of plague in 1529 was outstanding and contributed to his already growing reputation. In De Historia Stirpium he gave full recognition to his artists by praising them in his preface and publishing their portraits in the back of the book. Their renderings demonstrate the Renaissance shift to accurate observation and drawing of plants from life. Fuchs would be immortalized in the genus Fuchsia.

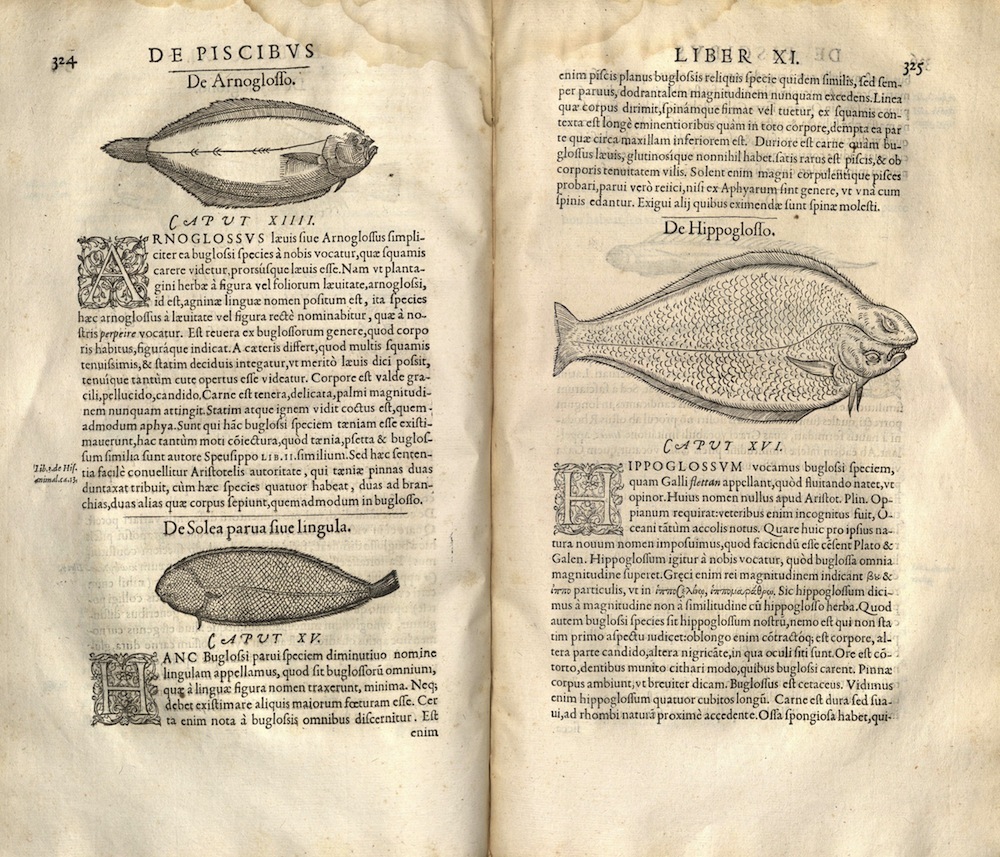

Lugduni: M. Bonhomme, 1554-1555

First edition

QL41 R6

Guillaume Rondelet was one of the first of sixteenth century scientists to break with the eighteen-hundred-year-old tradition among natural historians of quoting or commenting on Aristotle’s knowledge of animals and begin the practice of gathering and reporting information gained firsthand. This book contains accurate illustrations of the egg cases and immature eggs of several fish, based upon Rondelet’s own meticulous studies. The work is an example of the change in attitude about science in the sixteenth century.

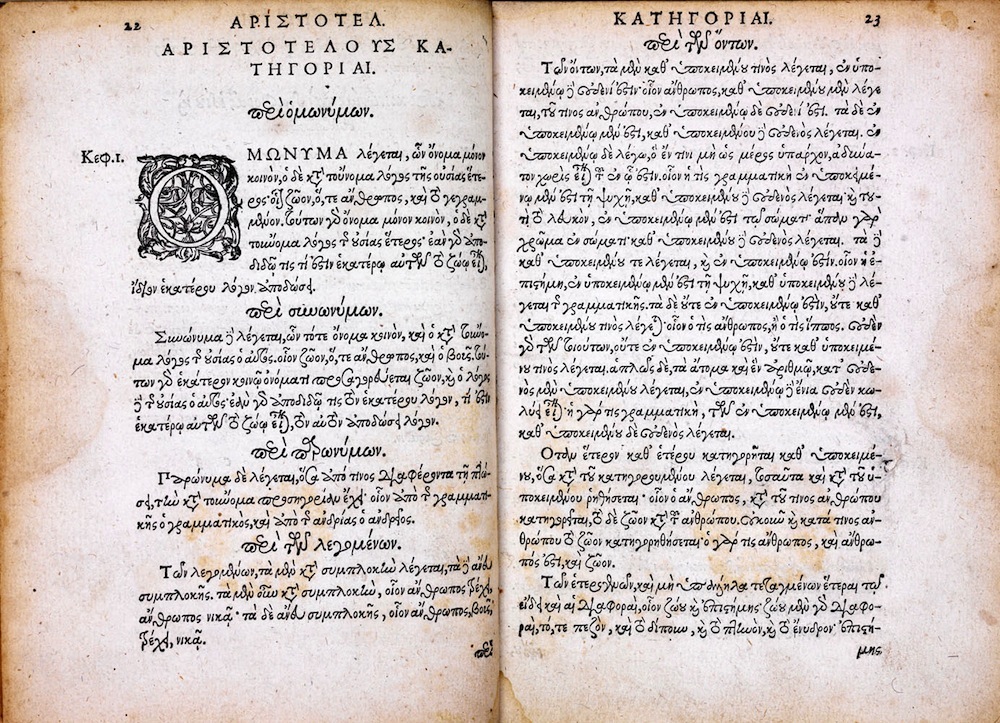

Francofurti, Excudebat A. Wechelus, sibi & T. Guarino, 1577

PA3893 O7 1577

Of all the classical Greek scholars, the most influential was Aristotle. He defined for the first time basic fields of inquiry: logic, physics, political science, economics, psychology, rhetoric, and ethics. In the process, Aristotle also established a method of study which profoundly influenced scholarship for nearly two thousand years. The Organum is a collection of four Aristotelian treatises. This edition is a new and corrected version of an edition done by the learned French humanist Nicolas de Gouchy (ca. 1520-1572). University of Utah copy has widely scattered underscoring or brief neat annotations in an early hand. Printer’s device on title, woodcut initials and headpieces.

London: Printed for Henrie Tomes, 1605

First edition

B1190 1605

Francis Bacon’s belief in man’s sovereignty over nature was sorely tried by his conviction that the knowledge possessed by man was practically useless. It was this frustration that motivated him to found a new scientific methodology. In this work, commonly known as The Advancement of Learning, Francis Bacon suggested that it was impossible to accept that either all knowledge had been discovered by Aristotle or could be logically derived from his writings. Instead, Bacon proposed that knowledge should be based on direct observation of perceived facts, whether or not this contradicted the authority of the ancients. His emphasis on direct observation strongly influenced the development of an experimental method of scientific thinking in England. Bacon’s reorganized scientific method included careful and purposeful thought to the relation of science to public and social life. Charles Darwin began his Origin of Species with a quote from Advancement of Learning.

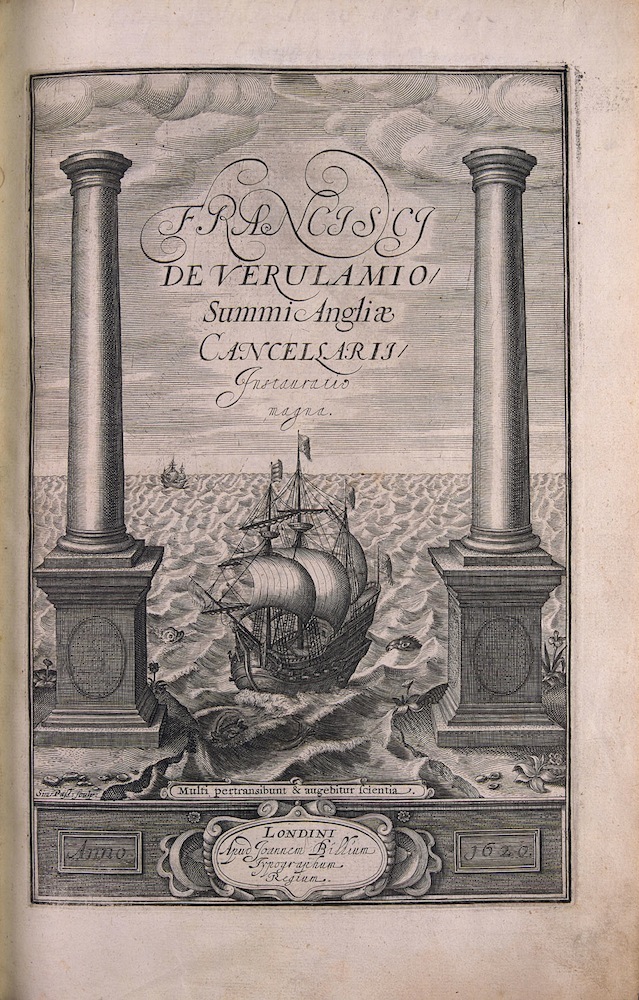

The foundations of modern objective science were laid down by Francis Bacon in this book. The title is in reference to the Organum of Aristotle. Bacon’s Novum Organum, as the title implies, advanced a new method of empirical reasoning. Bacon believed that experimentation was necessary to determine truth. He criticized the inadequate existing methods of scientific interpretation and provided a system based upon empirical methodology and the accumulation of reliable data. The title page of Novum Organum was a prophetic metaphor. In 1620, the course of philosophy, with Bacon as pilot, was substantially altered. Sailing through the Pillars of Hercules, the limit of the Old World, Bacon’s ship set out into new and uncharted seas, leaving behind a legacy of superstition and outdated methodologies. This voyage, as daring and influential as any undertaken by Renaissance explorers, ushered in a new era of scientific discovery.

London: Typis Du-Gardianis; ipensis O. Pulleyn, 1651

First edition

QP101.4 H35

English physician William Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood. Harvey studied medicine at Cambridge and at Padua University. Harvey was ahead of his time in obstetrics. This work contains the first original work on obstetrics published by an English author. Harvey included a careful anatomical description of the ovary of the hen, described the new-laid egg, then gave an account of the appearance seen on the successive days of incubation, and described the process of hatching. He described the uterus of the doe, the process of impregnation, and the subsequent development of the fetus. Harvey insisted from these and other studies that all animals arise from ova. The theories proposed in this book would not be proved until 1827. The engraved title-page depicts Jove holding a broken egg, out of which bursts all manner of animal and plant life, including a man, a reindeer, a grasshopper, and a dolphin.

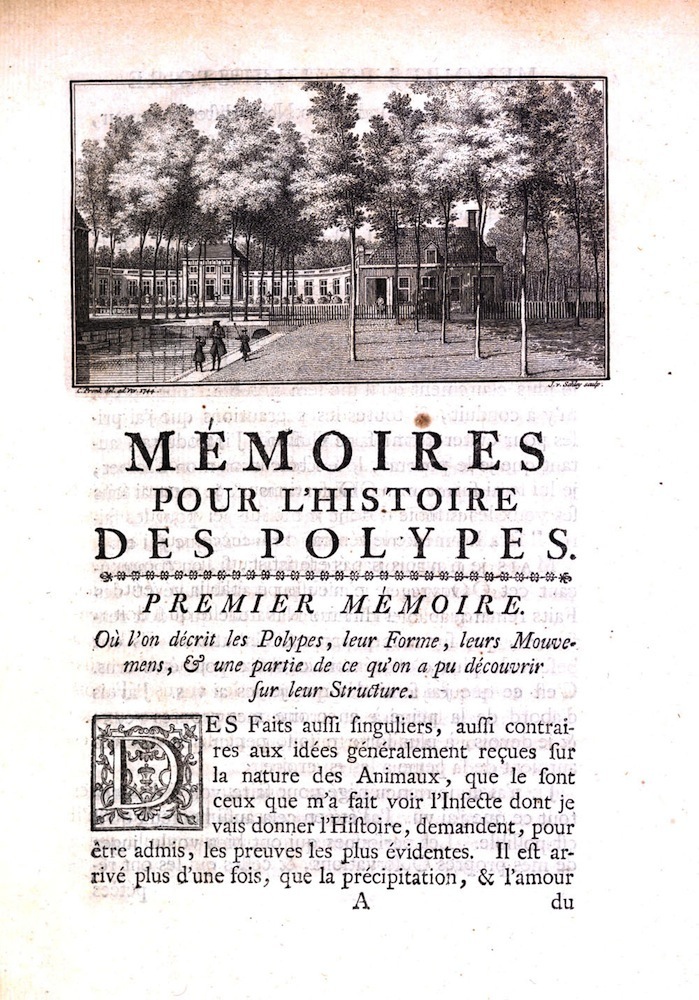

Leyden: Verbeek, 1744

First edition

QL375 T7 1744

As tutor to several children of various noblemen, Abraham Trembley became interested in the study of nature. He began studying polyps (today called hydra), which at the time were thought to be plants. In 1740, Trembley observed movement in the polyp’s appendages. Unsure of what he was witnessing (was it animal, mineral or vegetable?), Trembley experimented by cutting the polyp in half. If animal, it would die. If plant, it would live. Or so he surmised. Within a few days the two halves had grown into two new and perfect polyps. The tail grew a head and the head grew a tail. Trembley’s discovery, the blurring between plant and animal, had theological as well as scientific implications. What, for instance, happened to the animal’s soul? Did it divide in two as well? In fact, Trembley had isolated protoplasm and had found a common building block of life. The publication of Trembley’s findings included beautiful illustrations. It was important to Trembley that the readers of his book feel as though they witnessed the results themselves. Trembley understood the necessity of well-crafted, finely detailed illustrations in making his argument. To further legitimize his work he discussed the drawings and engravings in the preface and gave the credentials of the artists and the engravers.

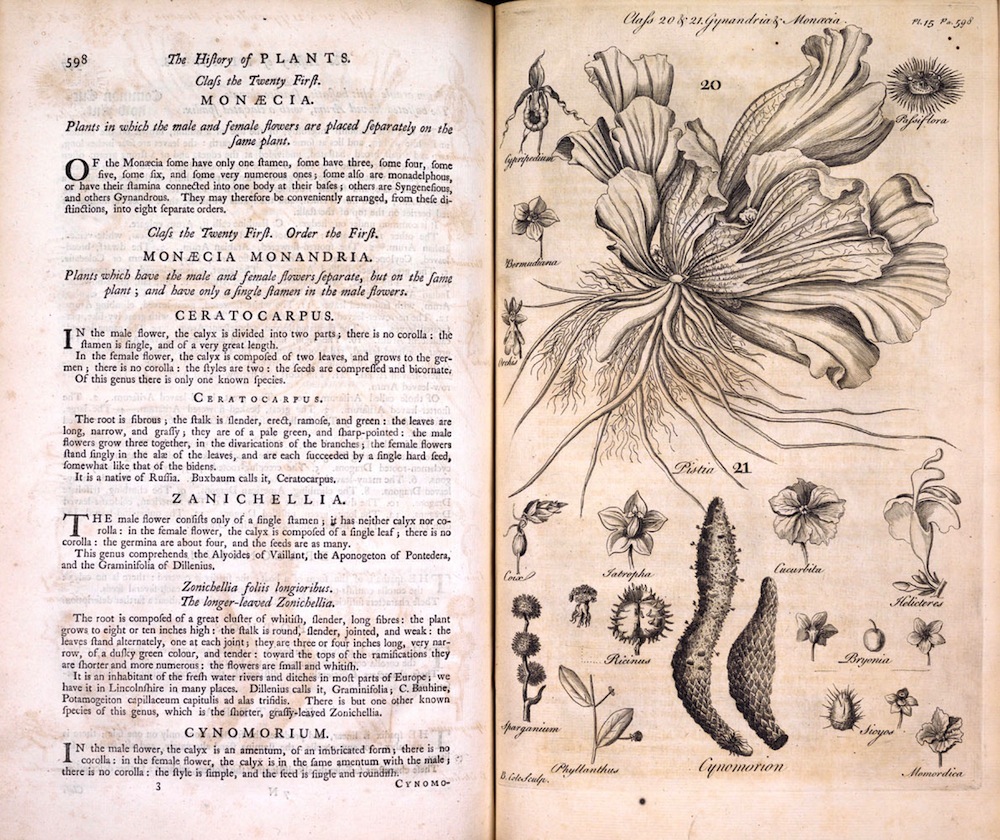

London: T. Osborne, 1748-52

First edition

QH15 H55 1748

Englishman John Hill was an apothecary by trade. He collected plants for use in herbal remedies and undertook several large projects in plant classification. The University of Utah copy is signed by past owner Jules Remy, a noted French naturalist and explorer who wrote a history of the Mormons. Sixteen uncolored plates of specimens. Bound in contemporary red morocco, rebacked, corners restored.

Paris : Panckoucke ; Liege, Plomteux, 1783-1808

First edition

QK7 L2

Jean Lamarck began his career as a botanist in 1778, eventually moving on to the study of zoology. In 1800, he began his study on the variation of species, which would lead him to conclude “…aided by much time and by a slow but constant diversity of circumstances [nature] has gradually brought about…the state of things which we now observe. How grand is this consideration, and especially how remote is it from all that is generally thought on this subject!” While in Paris he became a contributor to the Encyclopedie methodique. Lamarck invented the term “invertebrate,” preferring the title “Professor of Invertebrates” to “Professor of Worms and Insects.” He believed that few species died out, but, instead, went through modification. In spite of his findings, he staunchly placed the authority of the Bible over his own ideas. Of Lamarck, Darwin wrote: “[He] was the first man whose conclusions on the subject excited much attention…he first did the eminent service of arousing attention to the probability of all changes in the organic, as well as in the inorganic world, being the result of law, and not of miraculous interposition.”

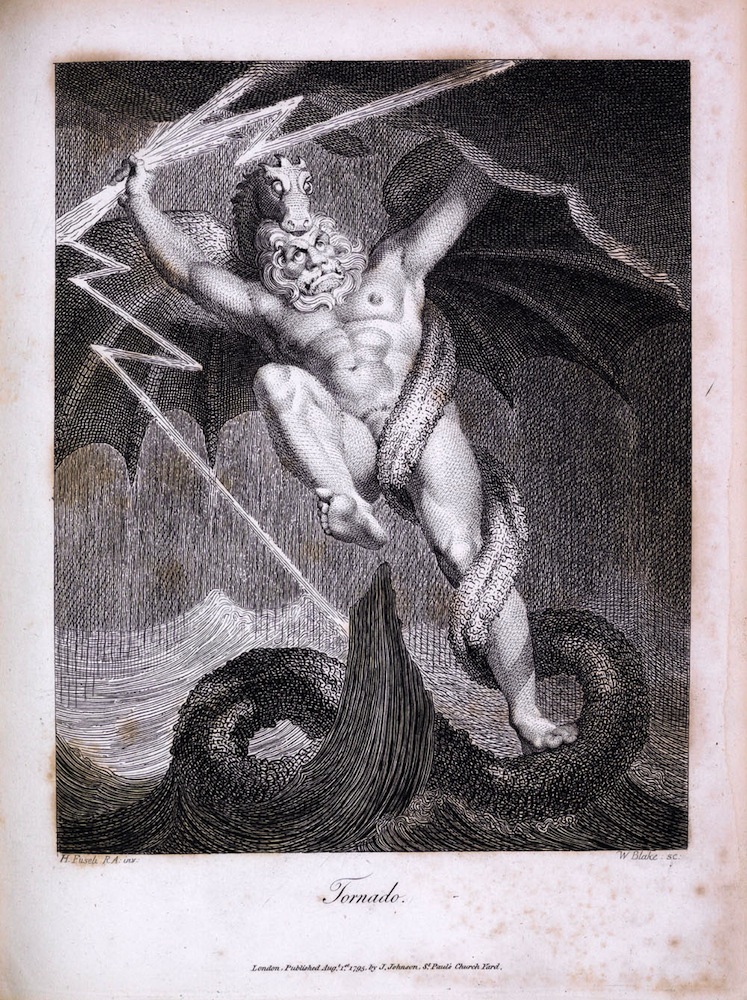

Erasmus Darwin was the grandfather of Charles Darwin. He was one of the leading intellectuals of eighteenth century England – a respected physician, philosopher, botanist, naturalist, and inventor. He formed one of the first formal theories on evolution. This long poem, The Botanic Garden, established Erasmus Darwin as one of the leading English poets of his day – Coleridge called him “the first literary character of England.” Some of the illustrations for this book were engraved by William Blake, after designs by Henri Fuselli.

London: J. Johnson, 1803

First edition

PR3396 A77 1803

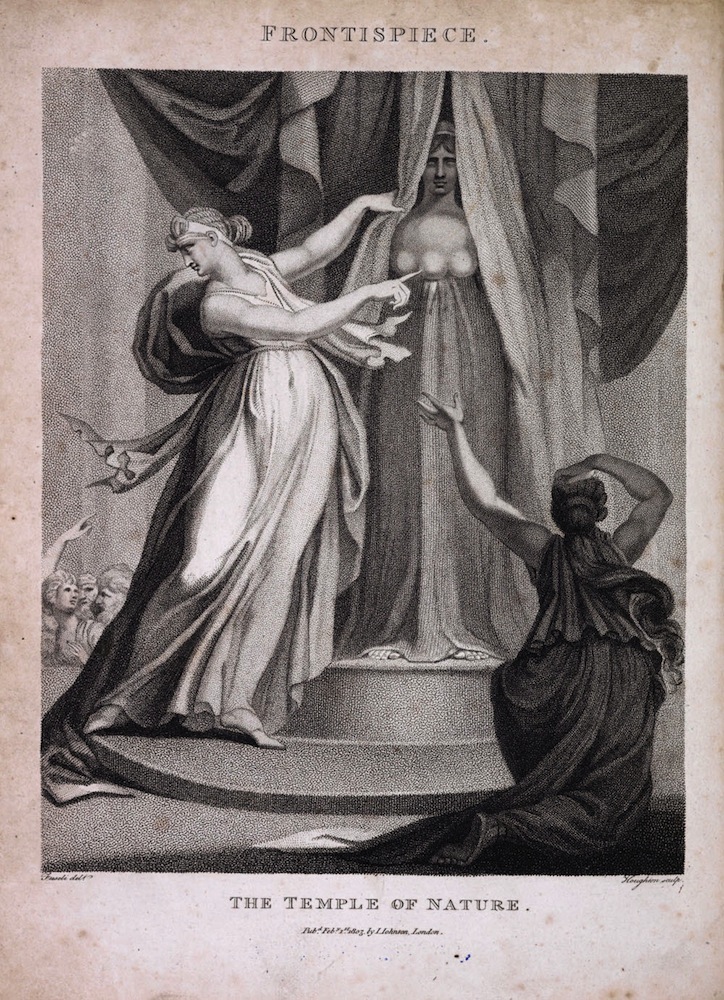

The Temple of Nature, published posthumously is Erasmus Darwin’s conception of evolution. It traces the progression of life from microorganisms to civilized society. With the exception of natural selection, Erasmus Darwin anticipated much of what his grandson, Charles Darwin, would later write about. Erasmus wrote: "Organic life beneath the shoreless waves/Was born and nurs’d in ocean’s pearly caves;/First forms minute, unseen by spheric glass,/Move on the mud, or pierce the watery mass;/These, as successive generations bloom,/New powers acquire and larger limbs assume;/Whence countless groups of vegetation spring,/And breathing realms of fin and feet and wing.” The original drawing for the engraving for the frontispiece was by Henry Fuseli.

London: J. Murray, 1820

First edition

HB161 M30 1820

Around 1838, as Darwin began developing his theory of evolution, he read Malthus’ writings regarding factors limiting human population growth. Reading Malthus’ works, Darwin later recalled thinking, “Why do some die and some live?...it suddenly flashed upon me…in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain – that is, the fittest would survive.” Darwin credited Malthus, among others, as his inspiration.

London: J. Murray, 1830-1833

First edition

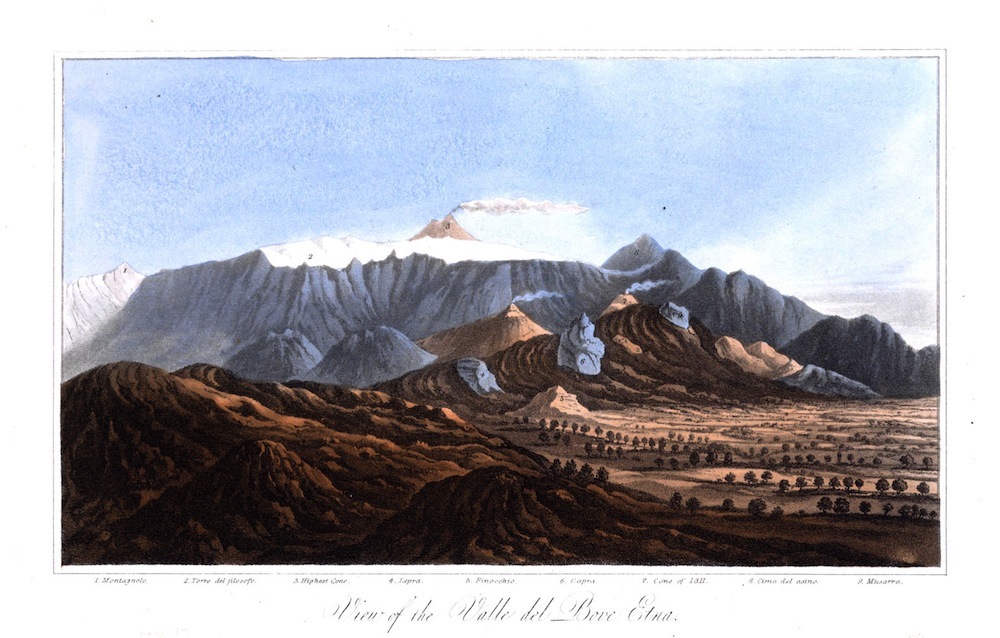

QE26 L956 1830

Charles Lyell studied geology under naturalist William Buckland. He traveled the English countryside to observe geological formations for himself. Much of the information in Principles, his first book, was based on these observations. The book had a huge influence on Charles Darwin, who took a copy of it with him on the HMS Beagle. Darwin looked at rock formations on this voyage “through Lyell’s eyes,” and Lyell’s information about stratigraphy inspired Darwin to think in terms of geologic time when it came to evolving organisms. After Darwin’s return from the Beagle voyage in October 1836, Lyell invited him to dinner, a meeting that began their close friendship. Throughout this friendship, Lyell rejected the idea of evolution. Darwin was hurt by Lyell’s reserve on the subject but, loyal through and through, said “Considering his age, his former views, and position in society, I think his action has been heroic.”

New York: G. & C. & H. Carvill, 1831

First English edition

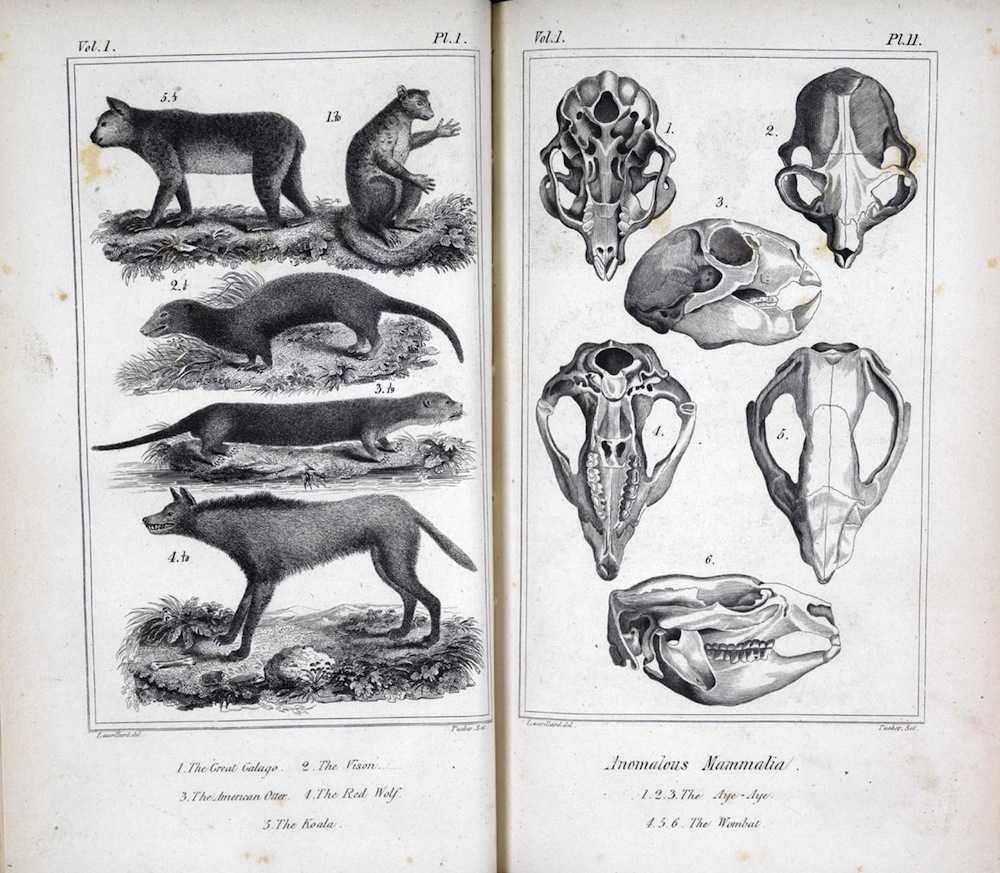

QL45 C945 1831

Georges Cuvier, anatomist and paleontologist, did not believe that life forms evolved over time. He believed any change in an organism would upset a natural balance, making it unable to survive. Cuvier classified animals into four branches, each sufficiently different from the other so as to disallow the possibility of any connection due to an evolutionary transformation. Similarities were due to common function, not common ancestry. Cuvier thus repudiated, quite harshly, the theories of contemporaries such as Lamarck. Cuvier’s most fundamental contribution to biology was to establish as fact the extinction of organisms – something that had been theorized by earlier scientists but was rejected still by those who could not believe that God, creator of all things “good” would allow their complete demise. Disappeared species were a matter not of change, said Cuvier, but “…the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.” Cuvier’s classic work was Règne Animal, which first appeared in 1817. It presented the results of his research on the structure of living and fossil animals and was translated into English many times, often with substantial notes and supplementary material as updates became available.

New York: Harper, 1832

First American edition

QH81 M83 1832

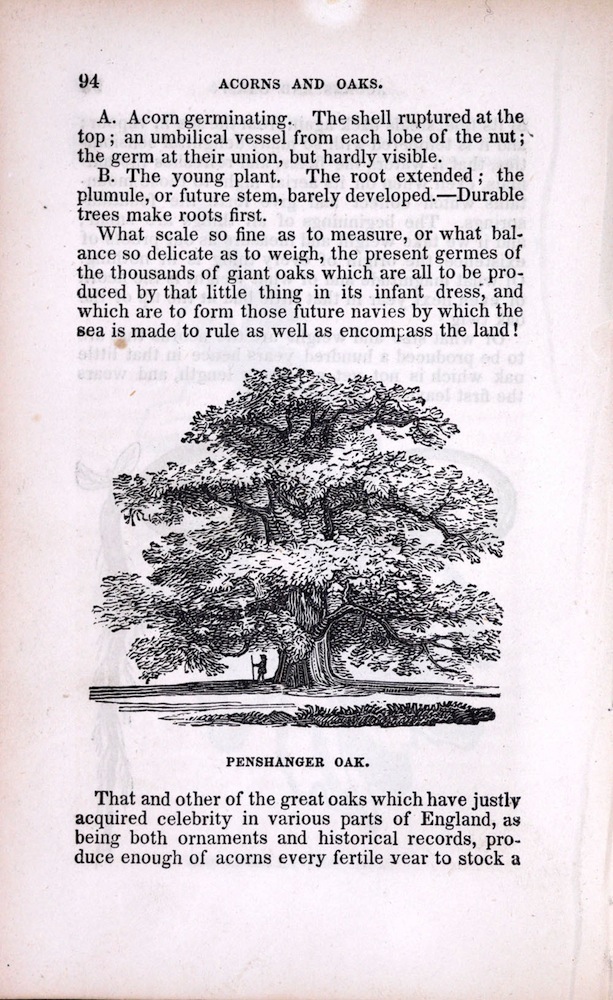

Robert Mudie was a newspaper editor and author, a self-taught artist and naturalist. His works, such as Popular Guide, were written for the layperson. Mudie’s writings were what the man-on-the-street would have been reading about the natural world just as Darwin began writing of his observations while on the H.M.S. Beagle. Mudie wrote that geophysical changes on the landscape, such as depleted forests or reclaimed marches, would effect climate which would then effect “wild production” and “the entire extinction of some of…both plants and animals…and the introduction of not varieties only, but species altogether new.” He further argued that, “it’s the general character only which descends by hereditary succession. When the young leaves the parent and becomes an independent being, it is controlled by circumstances, and must accommodate itself to them.” Reading this, the layperson would have been acquainted with some of what Darwin would soon put together in his coherent, well-argued and well-documented way.

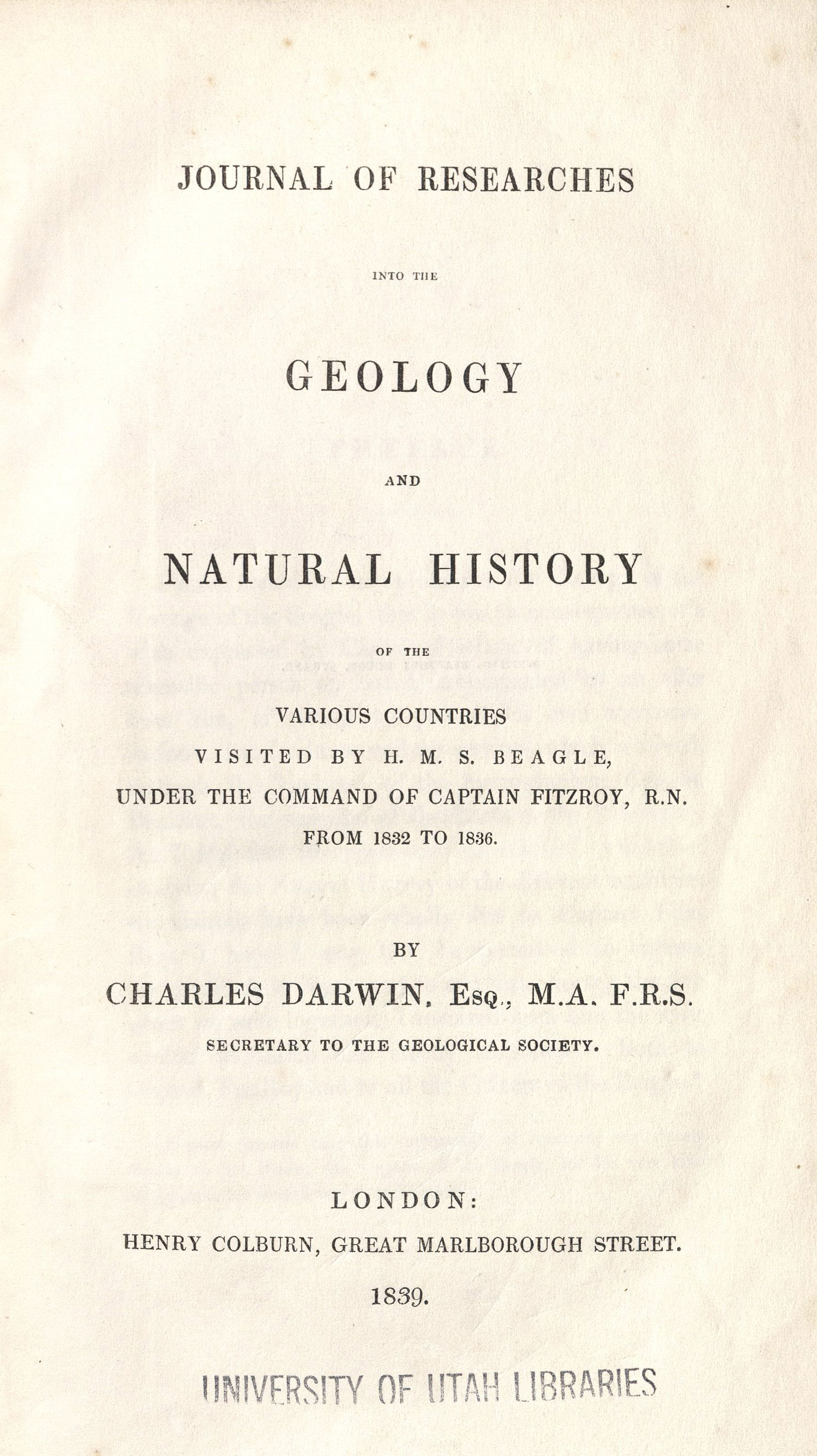

London: H. Colburn, 1839

First separate edition

QH11 D2 1839

Charles Darwin became a fellow of the Geological Society in January 1837. One year later he was elected secretary. He served, unpaid, as a naturalist on the H.M.S. Beagle during a British naval surveying voyage to South America in 1831. He became well-known for his diary of this voyage. First published as the third volume of Robert Fitzroy’s The Narrative of the Voyages of H.M. Ships Adventure and Beagle in 1839, it was published separately in the same year. The name of this work was changed four times during subsequent editions and is now known as “The Voyage of the Beagle.” In his diary, Darwin often mentions finding previously unknown species of plants and animals: “In my collections from these islands…there are twenty-six different species of land birds. With the exception of one, all probably are undescribed kinds, which inhabit this archipelago, and no other part of the world…”

Zoology was first published as a five volume unbound book in nineteen parts as they were edited and printed between February 1838 and October 1843. The parts were written by various authors, directed and edited by Charles Darwin. Darwin also contributed items to the Mammals and the Birds sections. The text of the Fish and the Reptiles sections include many notes by Darwin. Part 3, “The Birds,” was written by John Gould (1804 – 1881). Gould was an English ornithologist. Darwin turned to Gould for help in identifying bird species collected during voyage of the Beagle. It was Gould who told Darwin that Galapagos finches were a separate species, providing Darwin with essential information leading to his development of the theory of evolution. Gould also provided the bird illustrations for Zoology.

New York: W. H. Colyer, 1846

Second American edition

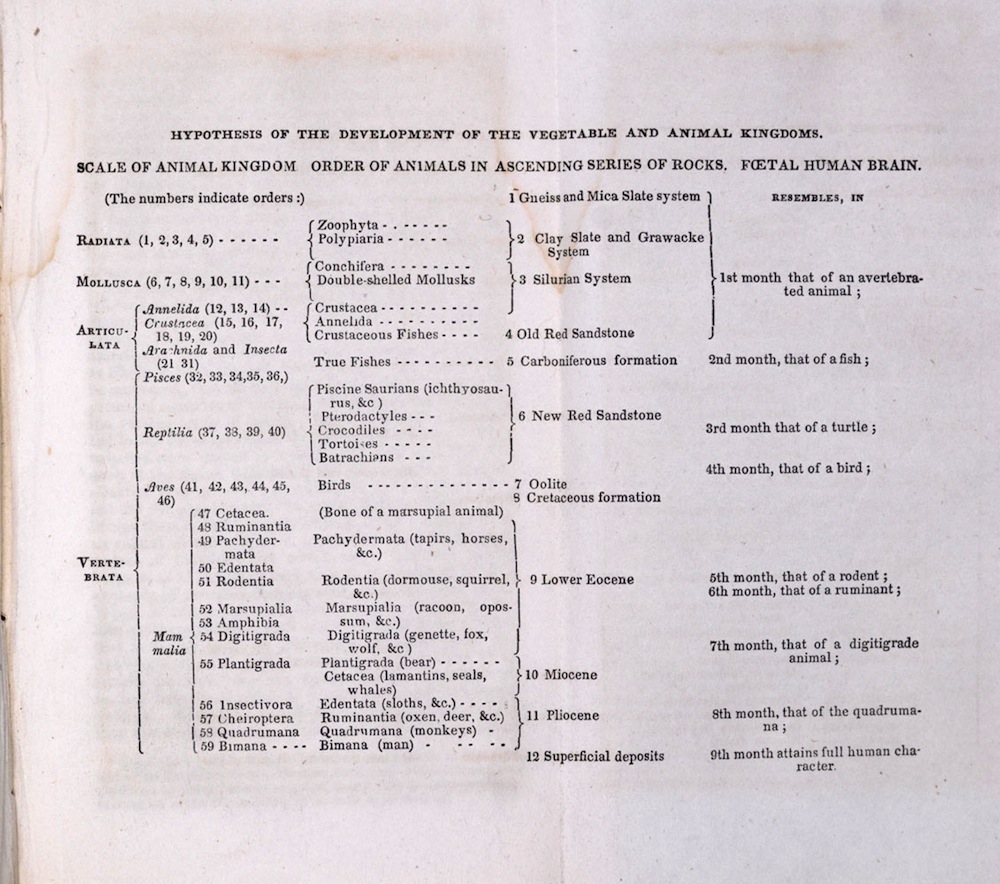

QH363 C4 1846

The first edition of Vestiges appeared in 1844 in London. More than twenty thousand copies were printed in various editions, including foreign editions, over the next sixteen years. The book caused a stir among naturalists of the day and the sensation it caused helped prepare the public for Darwin’s Origins in 1859. The at-first anonymous author placed evolutionary ideas amidst a broad history of the cosmos. Robert Chambers, an Edinburgh journalist, later revealed to be the author, declared that humans had arisen from monkeys and apes, as part of a progression of improving life-forms. The book became a Victorian best-seller – it quickly became the topic of conversation at soirees throughout Britain. The clergy hated the book and so, too, did many scientists of the day. It was not just bad theology, it was bad science. A review in the April 1845 issue of the North American Review said, “The writer has taken up almost every questionable fact and startling hypothesis, that have been promulgated by…pretenders in science… - he adopts them all, and makes them play an important part in his own magnificent theory, to the exclusion…of the well-credited facts and established doctrines of science.” Darwin’s reaction to Vestiges was mixed and cautionary. He, like other scientists, despaired of its speculation and factual carelessness. Another, younger biologist, Alfred Wallace, was far more receptive and would go on to formulate his own ideas toward theory of evolution. In the end, Darwin gave credit to both Wallace and “Mr. Vestiges” in his On the Origin of Species.

Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1850

Q171 H87 1850

Alexander von Humboldt studied geology in Frieberg under A.G. Werner, then recognized as one of the premier geologists in Europe. While in Frieberg, Humboldt met George Forester, the scientific illustrator who traveled with James Cook on his second voyage. The two hiked across Europe together. In 1792, Humboldt began work as a mines inspector. After the death of his mother he received a substantial inheritance, quit his job and headed to South America with a botanist, studying the flora, fauna and topography of the continent. In 1800 he mapped more than 1700 miles of the Orinco River. Humboldt returned to Europe and published, often at his own expense, many books about his findings. Charles Darwin described Humboldt as “the greatest scientific traveler who ever lived.”

Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & co., 1857

First edition, subscriber’s copy

GN23 N88 1857

Physician Josiah Nott is credited as the first to apply the insect vector theory to yellow fever, a serious health problem in his native South Carolina. He lost four of his own children to the illness. Nott is, however, perhaps better known for his theories on race. Types was his popular thesis on the polygenist theory; that is, the separate origins of races of humans. Based on the work of others writing at the time, Nott credited, in part, his personal observations in medicine as evidence. Nott used his theory to justify slavery, but also as a somewhat startling theological argument, saying that the human race must have descended from many different original pairs. Darwin cited this theory in The Descent of Man, later concluding that there was only one species of humans.

London: J. Murray, 1859

First edition

QH365 O2

After his return from his voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle, the significance of his observations led Darwin to revolutionary conclusions. Darwin was not the only scientist to advance the theory of evolution, but he spent twenty years working out its operation through the processes of natural selection before publishing this seminal work. The data he collected, the experiments he conducted, and the theories he proposed were all extremely influential in the disciplines of anthropology, zoology, geology, and ecology. The book caused a sensation, and the controversy over the mechanism of evolution continues unabated. His conclusions continue to be condemned, supported and debated one hundred and fifty years after this publication. Edition of one thousand two hundred and fifty copies. University of Utah's copy has author’s autograph mounted on title page.

New York: D. Appleton and company, 1860

First American edition

QH365 O2 1860a

Published in the United States one year after the London first edition, on the eve of the Civil War, one American reviewer wrote, “Is it too much to say that, in the good old times, opinions like these would have been strongly redolent of fagot and flame?” It was not until the 1870s that serious opposition to Darwin’s theories about natural selection began to mount in the United States. The argument against them was not scientific, but rather theological, much as it remains to this day.

London: J. Churchill, 1864

First edition

QL805 H98

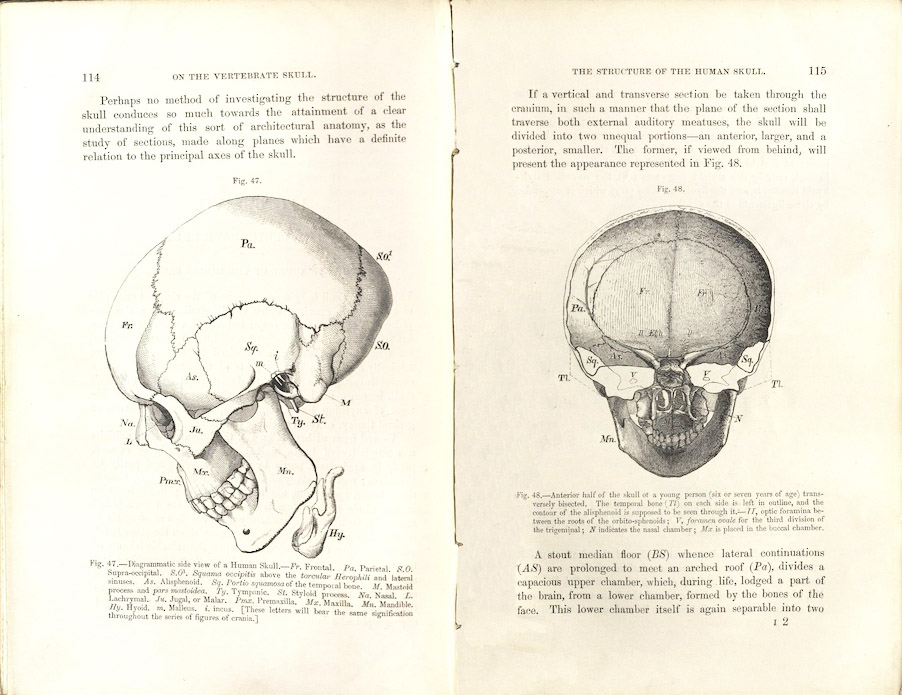

Thomas Huxley was well respected by his peers, in no small part, not in spite of, but because of his quick defense of Darwin. One contemporary reviewer of this work by Huxley wrote in North American Review January 1865, “He has faith in the doctrine of Transmutation of Species; and the instant Mr. Darwin’s book appeared, he published an earnest plea that it might have a fair and respectful hearing.”

London: R. Hardwicke, 1862

First edition

QH367 H982

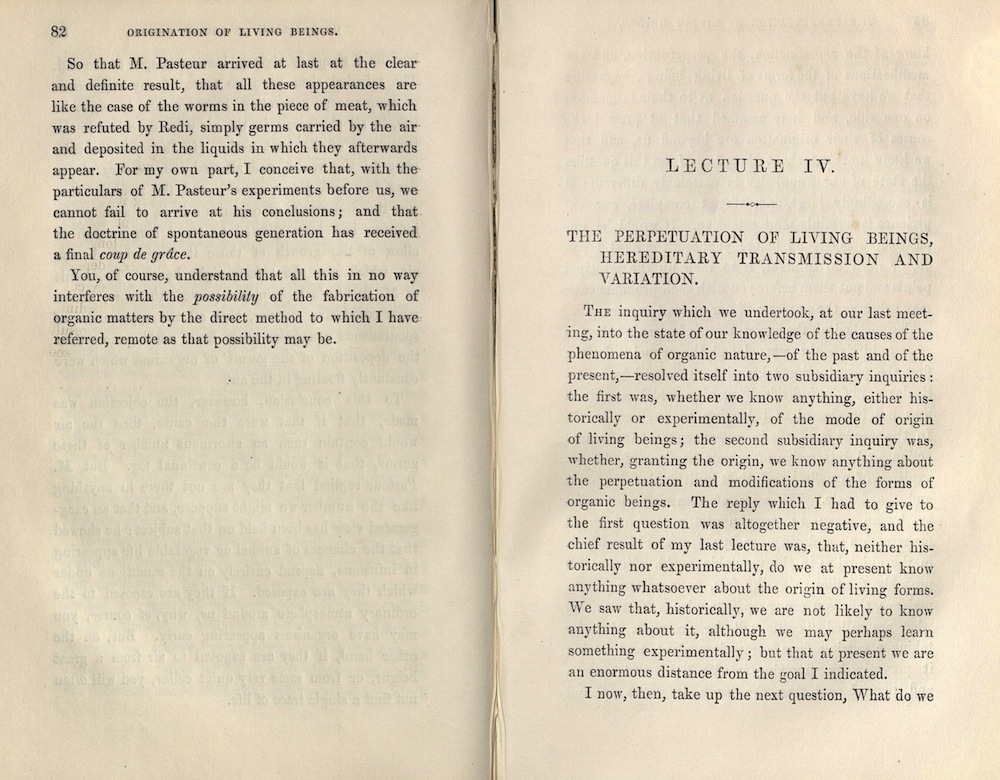

Scientist and philosopher Thomas Huxley became one of Darwin’s most immediate and vociferous defenders, publishing numerous articles and essays supporting Darwin’s theories on natural selection. Even so, Huxley differed with Darwin on some key points, namely Darwin’s slow, gradual evolution vs. Huxley’s belief in a sudden explosion of new species. Around 1855, Huxley began a series of lectures designed specifically for working-class men, calling them “People’s Lectures.” They were well attended and Huxley enjoyed speaking to these groups very much: “I want the working class to understand that Science and her ways are great facts for them – that physical virtue is the base of all other, and that they are to be clean and temperate and all the rest – not because fellows in black and white ties tell them so, but because there are plain and patent laws which they must obey ‘under penalties.’” The essays contained here were written for “working men.”

London, Edinburgh: Williams and Norgate, 1863

First edition

QH368 H96

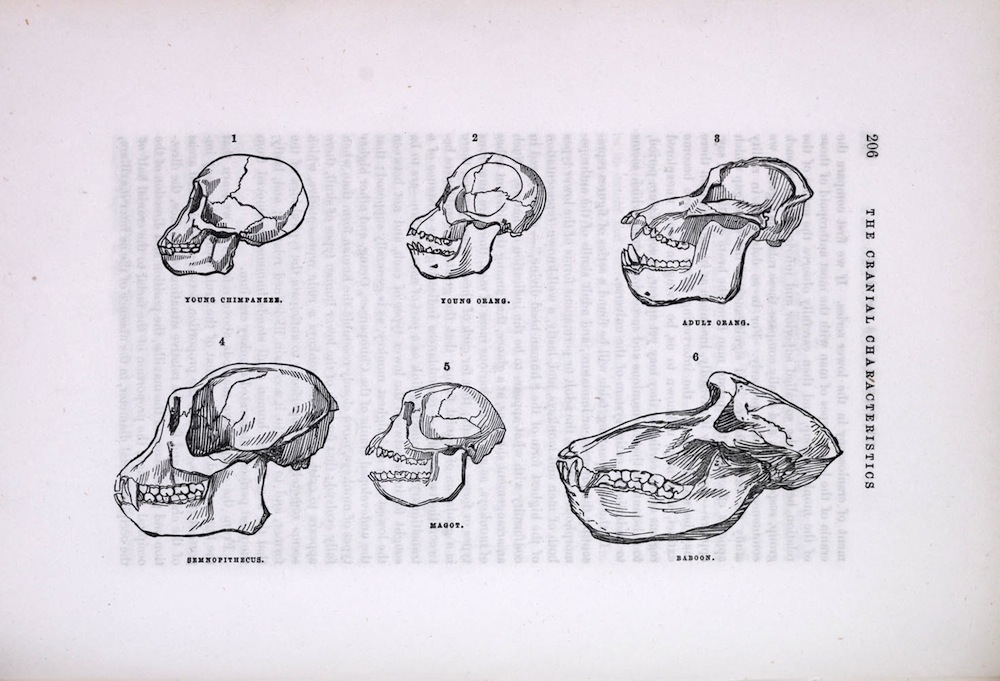

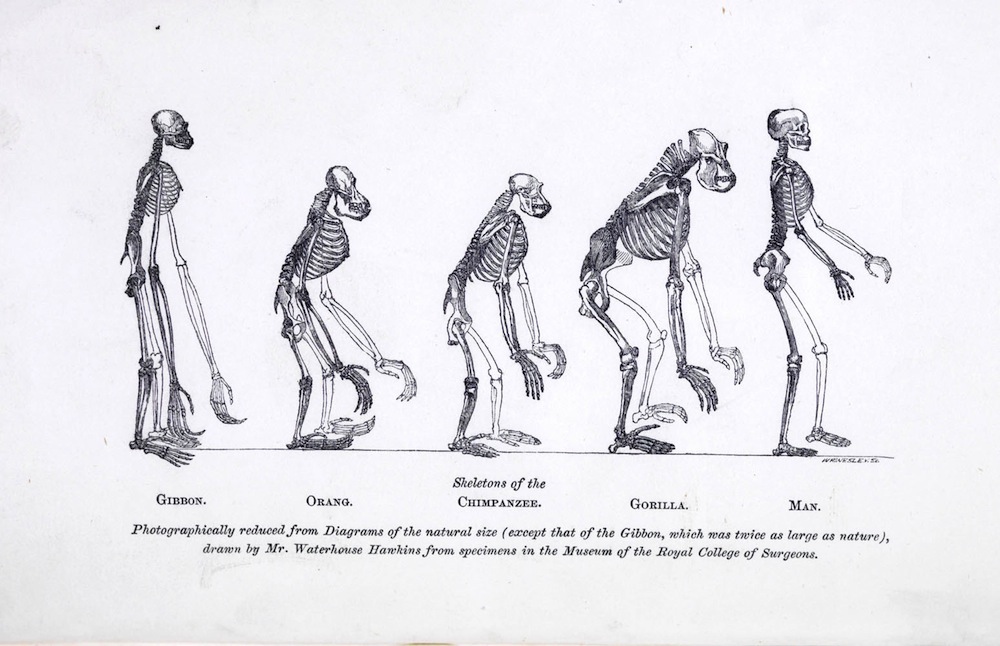

Thomas Huxley jumped at the chance to defend Darwin. In a letter regarding the publication of Origin of Species, dated November 23, 1859, he wrote, “As for your doctrines I am prepared to go to the Stake if requisite. . . I trust you will not allow yourself to be in any way disgusted or annoyed by the considerable abuse & misrepresentation which unless I greatly mistake is in store for you. . . And as to the curs which will bark and yelp – you must recollect that some of your friends at any rate are endowed with an amount of combativeness which (though you have often & justly rebuked it) may stand you in good stead – I am sharpening up my claws and beak in readiness.” Huxley expanded on Darwin’s theories. He wrote that the visible characteristics of man differed less from the more sophisticated apes than did the latter from the lower members of the same order of primates. Evidence was Huxley’s most important work, offering the first synthesis of the anatomical and embryological evidence of human evolution. The frontispiece is an illustration comparing the skeletons of various apes to that of man.

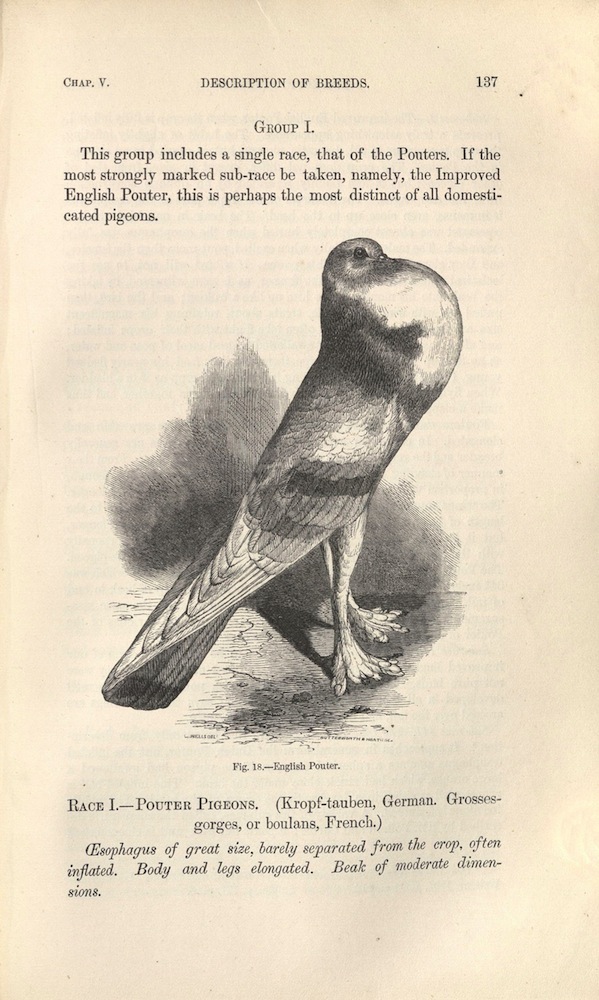

Variation includes, along with Darwin’s study of variation in pigeons and plants, his provisional theory of “pangenesis,” an attempt to explore the causes of variant forms beyond their survival or selection.

London: J. Murray, 1871

First edition, first issue

QH365 D2 1871

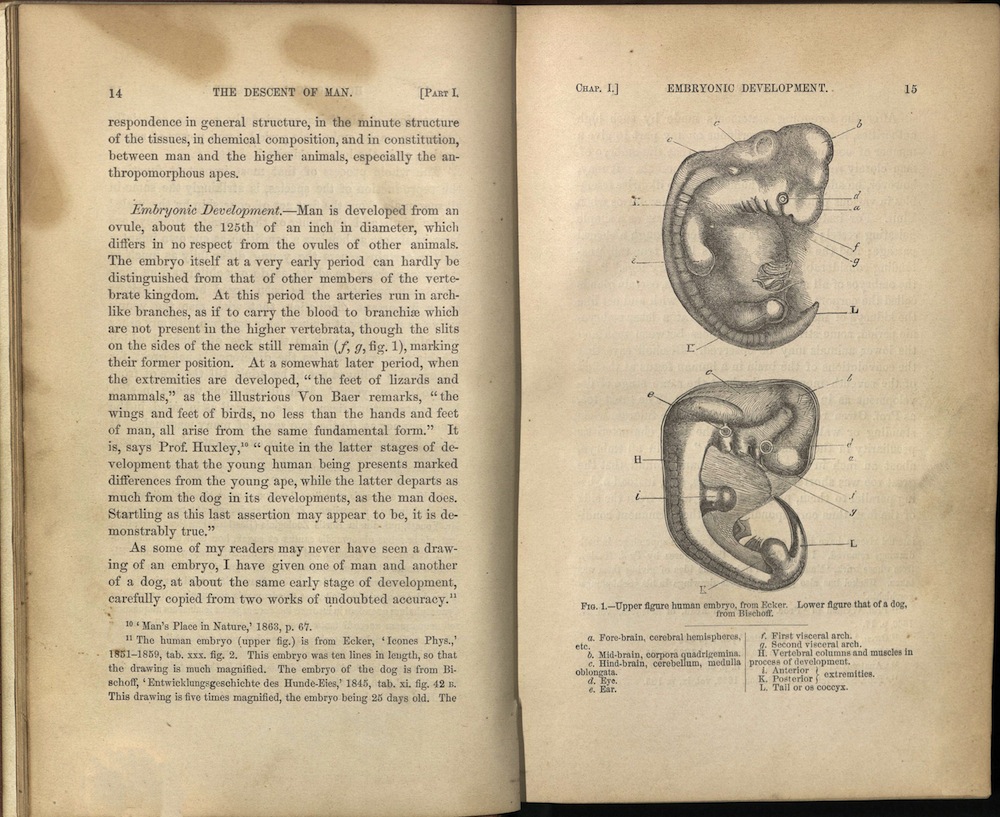

“Man still bears…the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.” In Descent Darwin used the word ‘evolution’ (vol. 1, p. 2) for the first time. Darwin reflected on whether humans, like other species, are descended from a pre-existing form and considered the means of homo sapien development. More than a decade after the publication of Origin of Species, Darwin applied his theory of natural selection to the emergence of the human species. He had the benefit of debates that were already under way, and he included these discussions in his theory.

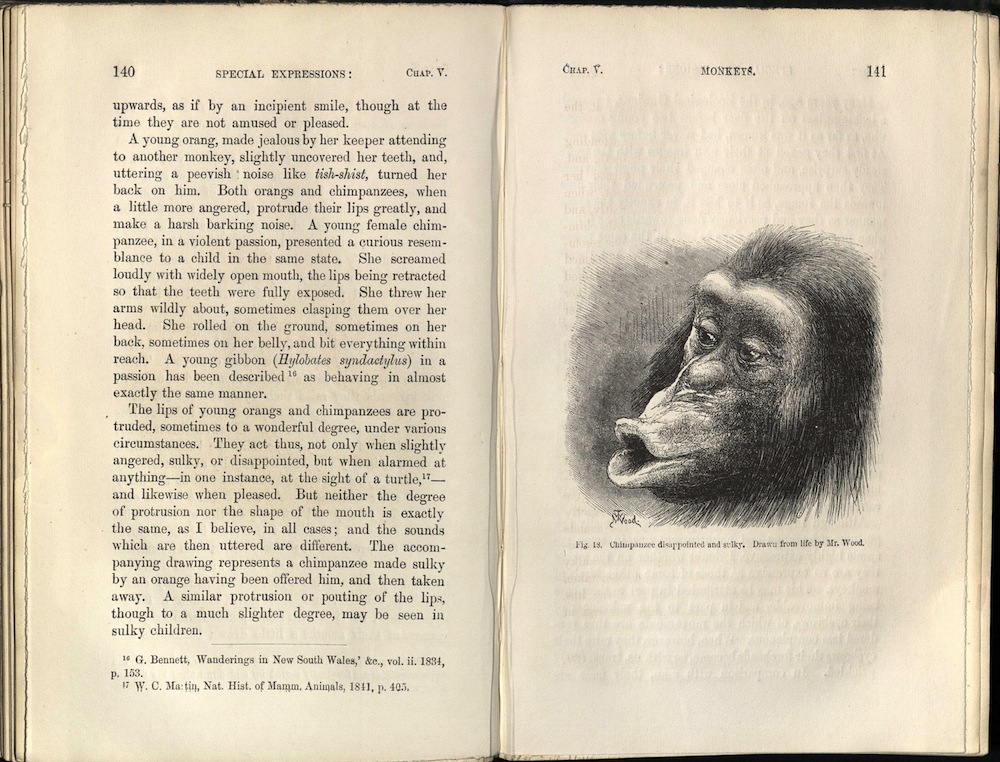

In Descent, Darwin presented examples supporting his contention that humans and animals shared cognitive attributes like wonder, curiosity, long-term memory, the ability to focus, the ability to imitate the behavior of others, and the ability to reason. Darwin wrote Expression to refute current speculation that human ability to manifest emotion through a wide variety of facial expressions indicated a species separated from evolutionary concepts. The book was based upon and included a pamphlet Darwin wrote on the topic in 1867. Darwin had done no research on the subject, but included the thinking of many of his peers in his denial of the theory. Edition of seven thousand copies.

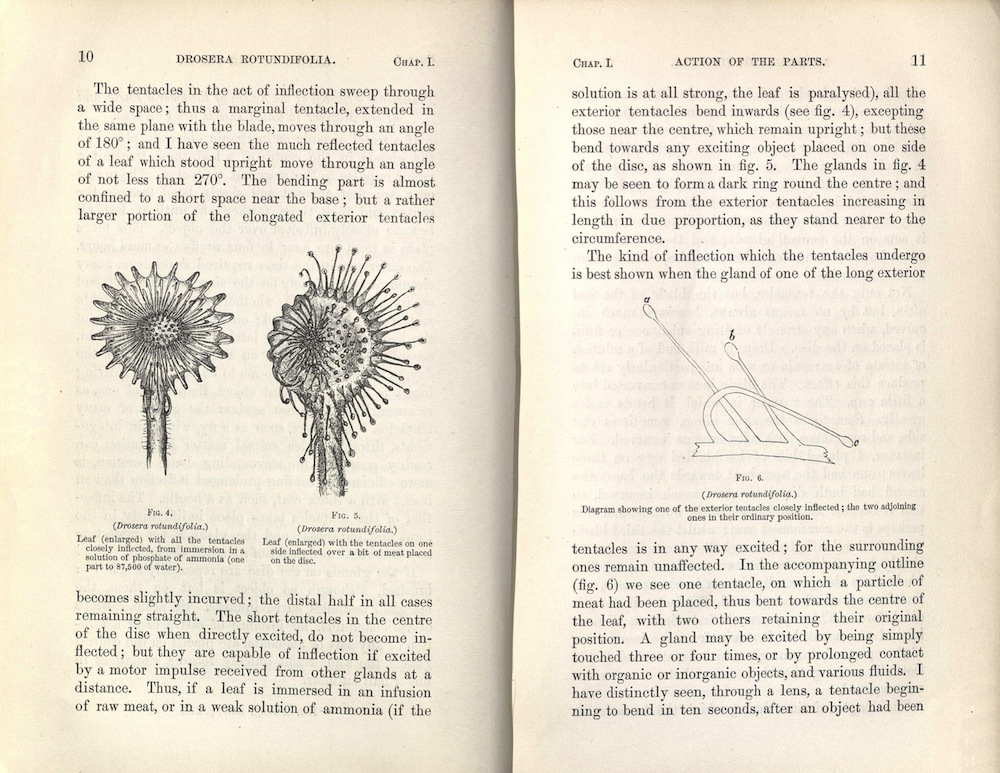

In this study of the adaptations of plants to impoverished conditions, Darwin described the assimilations for survival purposes, in some cases, as “murderous propensities.” Darwin drew figures 7 and 8, while his sons produced the rest of the drawings. The book was published in a standard binding without inserted advertisements, announcing a print run of three thousand, twenty-seven hundred of which were sold to the book trade. The book was not printed again in Darwin’s lifetime. University of Utah copy inscribed on title-page “From the Author.”

London: J. Murray, 1876

First edition

QK926 D23

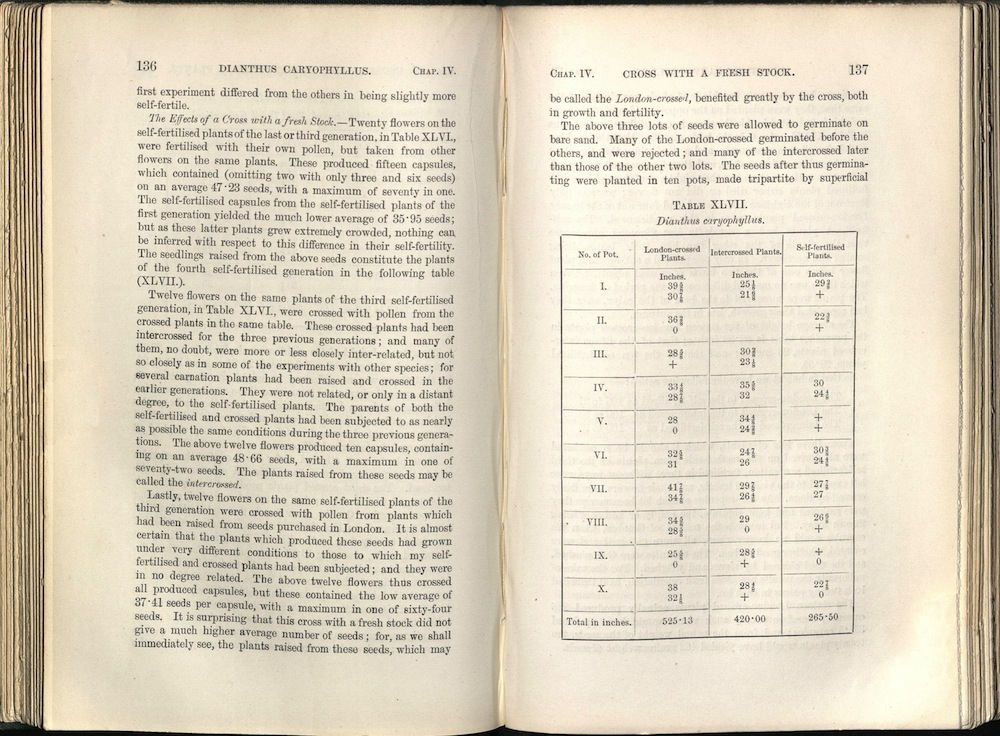

Effects is a highly technical and detailed study of natural systems that favored cross-fertilization and the advantages of those mechanisms. Darwin wrote, “…the results…explain, as I believe, the endless and wonderful contrivances for the transportal of pollen from one plant to another of the same species.” Fifteen hundred copies sold in less than two months.

New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1876

First edition

QH367 G77 1876

Asa Gray, a respected American botanist, corresponded with Charles Darwin regarding his study of plant distribution, helping Darwin with the theories elaborated upon in On the Origin of Species. He was a staunch supporter of Darwin in America. His collection of essays, Darwiniana was very influential. In these essays, Gray suggested that Darwinian evolution and the tenets of Protestant Christianity were not mutually exclusive. Gray wrote, “the most puzzling things of all to the old-school teleologists are the principia of the Darwinian.” Gray said that he was convinced that the present species were not special creations, but rather derived from previously existing species.

London: John Murray, 1877

First edition

QK926 D215

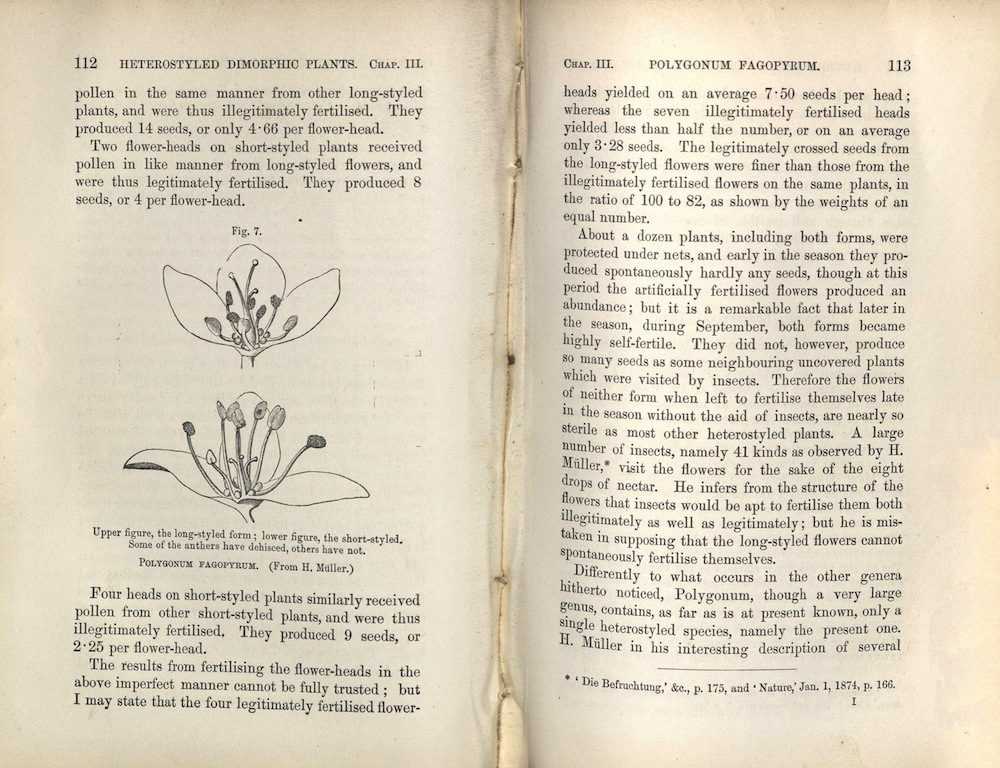

Much of the content of Different Forms had been published already in the Journal of the Linnean Society of London and other journals. Like The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilisation, the work was too technical to draw a large readership. The first edition was a print run of twelve hundred and fifty copies. Only two thousand copies were sold in Darwin’s lifetime. Sales, however, meant nothing to Darwin’s own enthusiasm in the minutiae of his work. In his autobiography, Darwin wrote of this study, “no little discovery of mine ever gave me so much pleasure as the making out the meaning of heterostyled flowers.”

London: John Murray, 1880

First edition

QK771 D22 1880

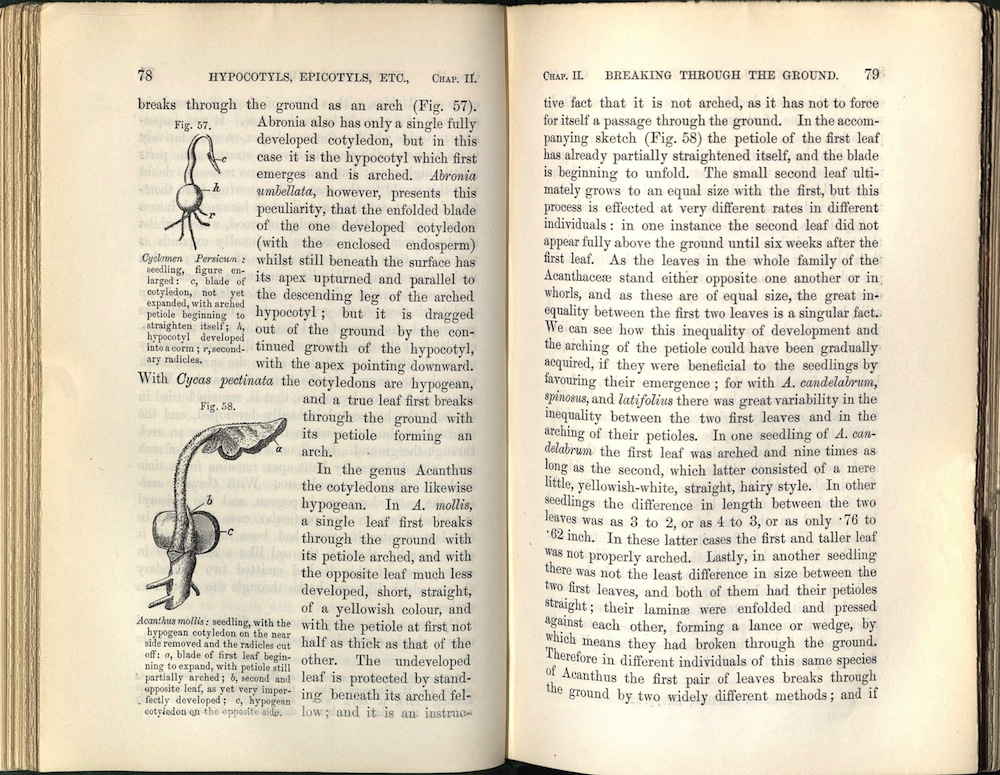

This study on phototropism in plants is a continuation of Darwin’s work on climbing plants. Darwin’s son, Francis, contributed to the experiments for this book and helped write it. The book sold fewer copies than any of Darwin’s other books, with a first issue of only fifteen hundred, although the two further issues printed before 1882 consisted of a thousand copies more each.

London: Macmillan, 1880

First edition

QH85 W18 1880

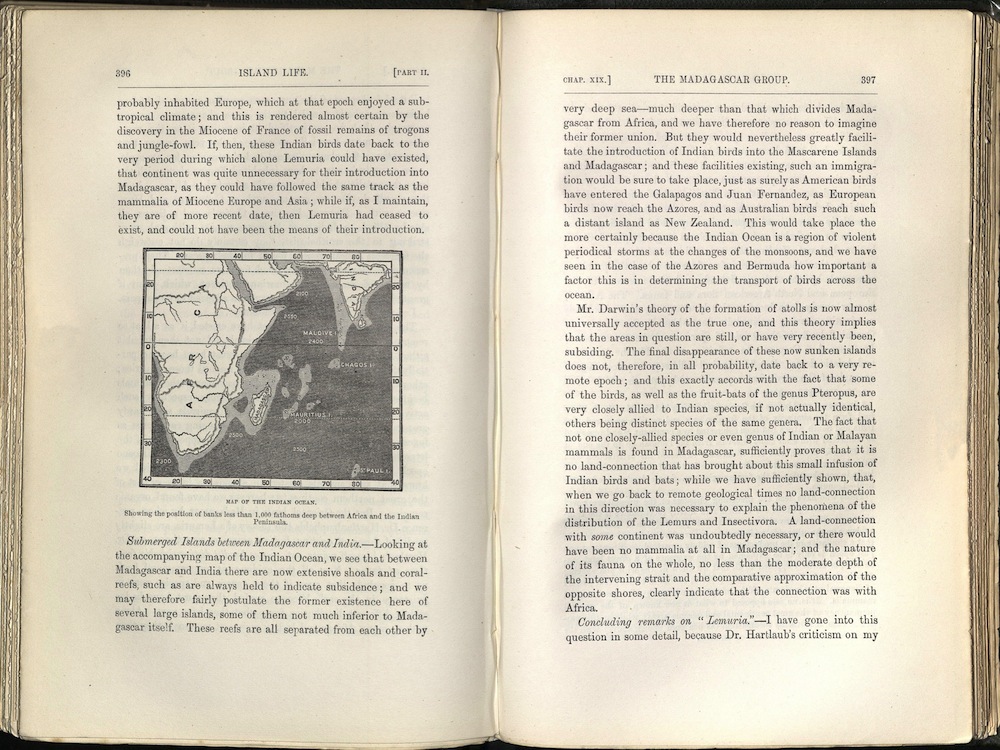

Alfred Russel Wallace corresponded with Charles Darwin for many years. Wallace first contacted Darwin while living in what is now Indonesia, collecting biological specimens and sending them home to England. Wallace, in his travels and studies, had come to a theory of evolution much like the theory that Darwin had been carefully developing for decades. Wallace described his theory as a “struggle for existence.” When Vestiges was first published, Wallace was particularly receptive to many of its ideas regarding the natural world. Vestiges inspired Wallace to collect his own evidence “with a view to the theory of the origin of species.” By 1848 he had saved enough money from his wages as a railroad surveyor to sail for the Amazon. As Wallace began collecting specimens he considered the distribution of species and whether geographic barriers, such as a mountain range or a river, could be a key to their formation. Returning to England in 1852, Wallace’s ship caught fire and sank. His drawings, notes, journals, and specimens were all destroyed. Wallace immediately began another collecting trip in the islands of Southeast Asia. In 1856, he published his first paper on evolution, focusing on the island distribution of closely related species. Darwin encouraged Wallace but cautioned him to work slowly and publish carefully. In 1858, recovering from malaria, Wallace wrote to Darwin, “It occurred to me to ask the question, Why do some die and some live?...it suddenly flashed upon me…in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain – that is, the fittest would survive.” Of his many publications, Island Life is considered Wallace’s finest thinking and writing, treating the causes and influences of glacial processes, and the nature of insular biota.

London: John Murray, 1881

First edition

QL394 D3 1881

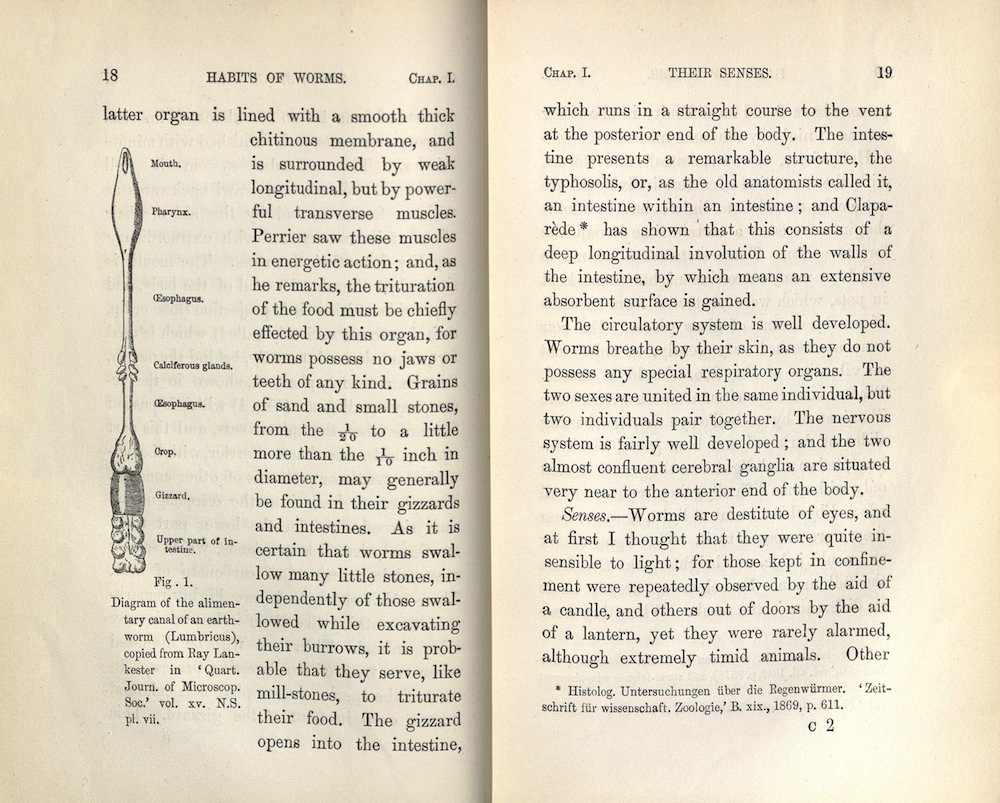

Darwin never lost his early interest in geology. For thirty years, Darwin dug in fields behind his house that had been undisturbed by man for years. He found that substances that had been on the surface of the ground were buried inches beneath the grass. He hypothesized that activity of earthworms was the reason for the upheaval. He used a flat stone, or, as he called it, a “wormstone” to measure the movement of soil due to earthworms. For Darwin, this movement had important implications. A small force, over thousands or millions of years, could have significant impact on the geology of the earth. This book was immensely popular, selling six thousand copies within one year and thirteen thousand before the turn of the century. It sold faster than Origin had.

London, New York: Macmillan and Co., 1889

First edition

QH366 W2 1889

Alfred Wallace remained a staunch defender of Charles Darwin. In Darwinism he used data that he gathered on a trip to America to explain and defend the science of natural selection. He proposed that natural selection could drive reproductive isolation, a hypothesis that became known as the "Wallace Effect." Wallace had discussed this theory with Darwin as early as 1868. The ideas presented in this book are still being researched today. It was by far one of the best summaries of the state of Darwinism in the nineteenth century, but it also stated Wallace’s own theories on evolution and how his theories differed from those of Darwin. University of Utah copy inscribed “July – 1889 J.C.F. Grumbine. Grumbine was the British author of several books on the occult, including Christianity and Evolution.

EVOLUTION : THE MODERN SYNTHESIS

New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1943

First American edition

QH366 H85 1942

The twentieth century ushered in a period of prolific research in genetics. Julian Huxley’s book on the subject of evolution as synthesis received rave reviews. The American Naturalist called it “the outstanding evolutionary treatise of the decade, perhaps of the century.” In Evolution Huxley coined the phrases “evolutionary synthesis” and “modern synthesis.” Modern synthesis connected Darwin’s conclusions about natural selection with Gregor Mendel’s study of genetics. Julian Huxley was the grandson of Thomas Huxley. University of Utah copy gift of Joyce Ogburn.