Public Sentiment

Checklist for "Public Sentiment"

Curated by Luise Poulton, 2010

Exhibition poster designed by David Wolske, 2010

Digital exhibition produced by Alison Elbrader, 2012

Format updated by Lyuba Basin, 2020

2011 marks the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the American Civil War (1861-1865). Slavery was the issue that brought the young country to war against itself. But before a shot was fired, the war was first fought on paper. For more than one hundred years before the advent of the war, British and Americans wrote impassioned treatises on the subject of slavery. Poetry, prose, fiction, and non-fiction appeared by well-known authors, politicians and travelers; by those not so well-known, and by those soon to become household names. Passionate writings, on both sides, were published in newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, and small, plain, inexpensive books. The eloquent, often rowdy, noise of the written word reached a crescendo just before the war began. The pen, however, proved less mighty than the sword. The American Civil War meant the end of slavery in this country. It was the deadliest war in United States history.

An essay is a translation of a prize-winning essay Thomas Clarkson wrote in Latin while studying at Cambridge. Clarkson argued that the slave trade was, “contrary to reason, justice, nature, the principle of law and government, the whole doctrine, in short, of natural religion, and the revealed voice of God.” In 1787, Clarkson, with Granville Sharp, William Wilberforce and others, formed the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade to lobby members of Parliament for the anti-slavery cause. Clarkson did field research, studying slave ships to gather evidence against slavery. The work of the committee helped achieve the passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807, ending British trade in slaves. Clarkson continued to be active in the British anti-slavery movement until 1833, when the Slavery Abolition Act was passed. He then turned his efforts toward slavery in the United States. Clarkson was a friend of William Wordsworth, who wrote of Clarkson on the occasion of the passage of the Slave Trade Act, “The blood-stained Writing is for ever torn;/And thou henceforth wilt have a good man’s calm,/A great man’s happiness; Thy zeal shall find/Repose at length, firm friend of human kind!”

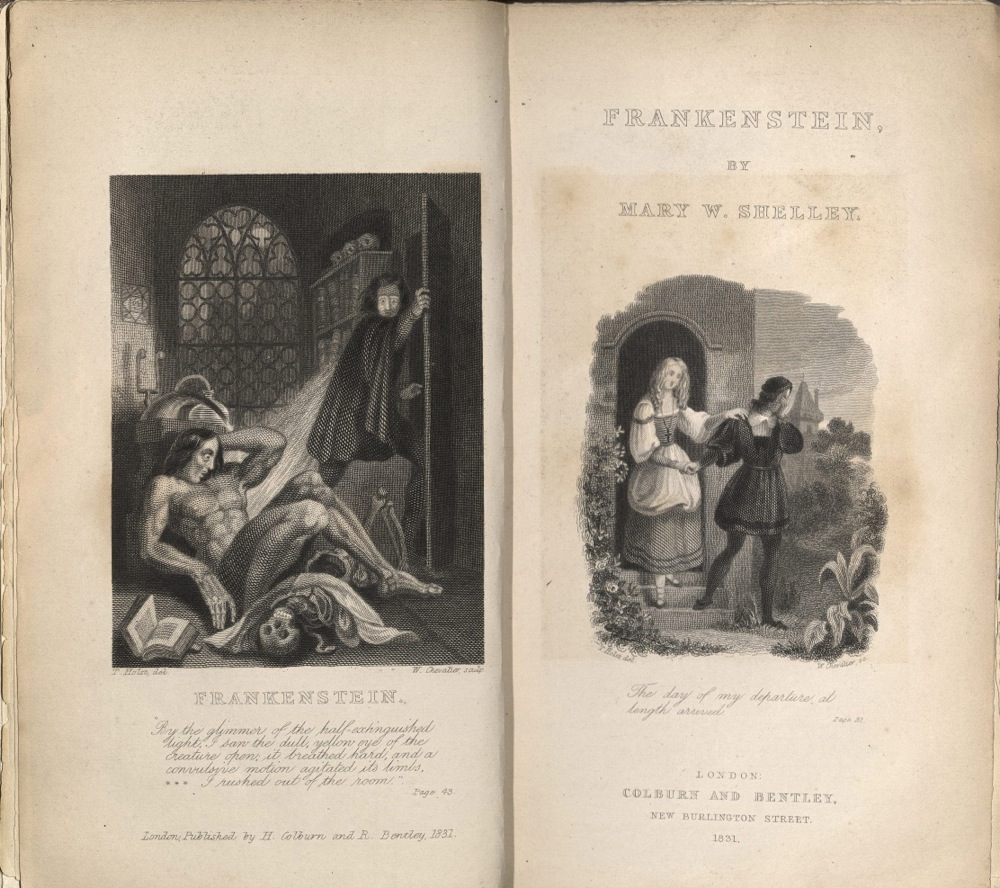

FRANKENSTEIN, OR, THE MODERN PROMETHEUS…

London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley…Bell and Bradfute, Edinburgh; and Cumin, Dublin, 1831

Ref., corrected, and illustrated/with a new introduction, by the author

PR5397 F7 1831

Frankenstein was first published anonymously in 1818 in an edition of five hundred copies of three volumes, a standard format of the time for novels. The first edition contained a preface written by Percy Bysshe Shelley and a dedication to Mary Shelley’s father, philosopher William Godwin. The novel had been rejected by Percy Bysshe Shelley’s publisher and by Lord Byron’s publisher. The second edition was released in 1823 as a two volume set with Mary Shelley’s name as author. The third printing was published in one volume as part of Bentley’s Standard Novels and also included other stories by Shelley. This edition included many revisions, although Shelley claimed in a new Introduction, that the revisions were “confined to such parts as are mere adjuncts to the story, leaving the core and substance of it untouched.” This is the first illustrated edition of Frankenstein. Engraved title-page and frontispiece illustrations engraved by W. Chevalier after T. [von] Holst. Each part has separate title-page and pagination. University of Utah copy gift of Eleanore Nichols.

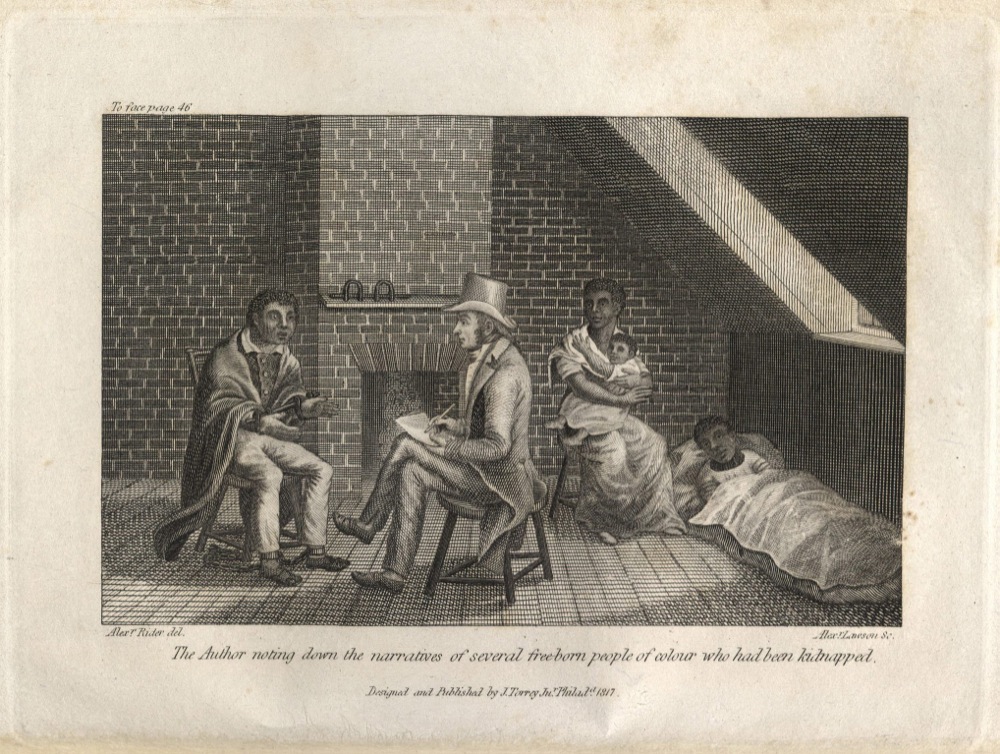

Philadelphia: Published by the author, John Bioren, printer, 1817

First edition

E446 T69

Philadelphia physician Jesse Torrey compiled interviews, narratives and first-hand observations for this illustrated book regarding the issue of slavery under the two-decades-old government of the United States. The text was compelling, but the engravings – depicting slave kidnappings, a profitable underground industry – made the subject more so. One engraving portrays Torrey, sitting in a cabin with a writing pad on his lap as an escaped slave talks to him. In the background a woman with babe in arms looks on.

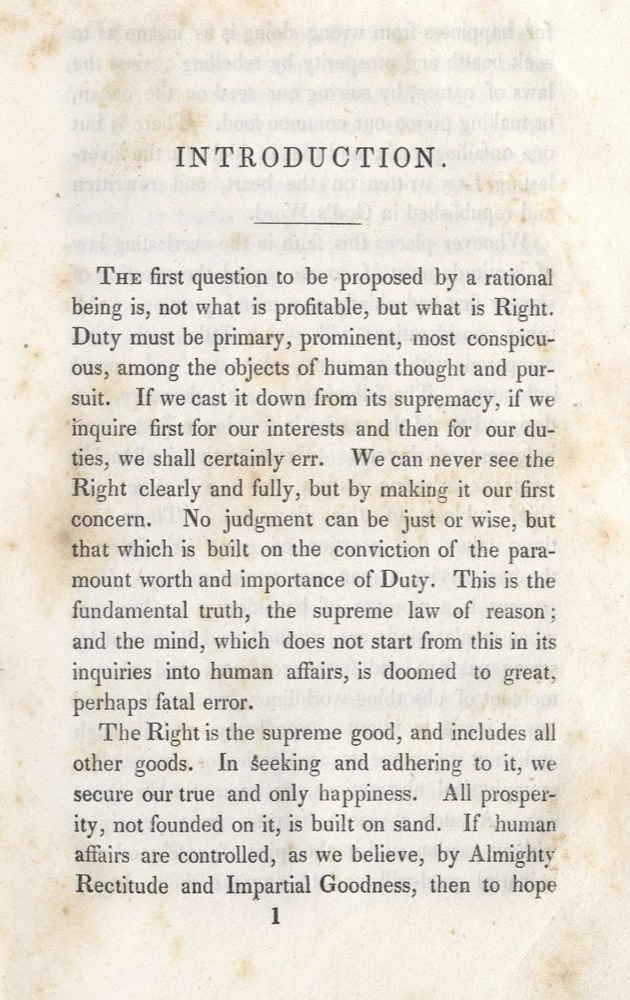

Harvard educated, William Channing was a leader in the Unitarian church and a strong influence on the New England transcendentalists. He was a keen admirer of the writings of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. He worked closely with education reformers such as Bronson Alcott and Horace Mann. In Slavery he argued that slavery was a moral corruption on slave and slave owner, but that, if freed, Africans would need supervision, to prevent their natural laziness. Former slave masters would fit the bill as overseers. His stance on the topic was so ambivalent, one wonders why he bothered. Anti-slavery friends and colleagues were dismayed at his moderation.

Boston: Russell, Shattuck and co., and J. H. Eastburn, 1835

First edition

E449 C4555

“But, says Dr. C. – alarmed, unquestionably, at the dangerous precipice to which he was tending – ‘government, indeed, has ordained Slavery, and to government the individual is in no case to offer resistance.’ Such a sentiment is fit only for a slave…Government is to be resisted by the sacred right of revolution and the inherent and original right of rebellion, in those extreme and dreadful emergencies which carry with them their own justification. If government, when without right and against moral principle and Christian duty, it subjects two millions of human beings to abject Slavery, whom God made free and intends, in his holy will, should continue to be free – if government may not, in such case, be resisted by them, all our sentiments of freedom are wrong – all reverence for our own revolution is folly – all respect for the liberty we enjoy is no more than idle pretension and senseless extravagance.”

John Greenleaf Whittier was a fan of Charles Dickens’ novels on the plight of the poor and oppressed. His first collection of poetry was published by Boston abolitionists. It contained several attacks on slavery, including “Clerical Oppressors,” assailing southern religious officials for using Christianity as a defense for slavery, and “Stanzas for the Times,” addressing the hypocrisy of the commitment to freedom by a government that upheld slavery. His first poem appeared in 1826 in the Newburyport Free Press, edited by William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison would go on to give Whittier several editorships of small weekly newspapers. In 1833, with the encouragement of Garrison, Whittier began publishing anti-slavery works, dedicating the next twenty years to the cause. Although Nathaniel Hawthorne dismissed Whittier’s work as “poor stuff,” Whittier was highly regarded in his day.

Philadelphia: Printed by Merrihew and Gunn, 1838

First edition

F158.8 B83 P4

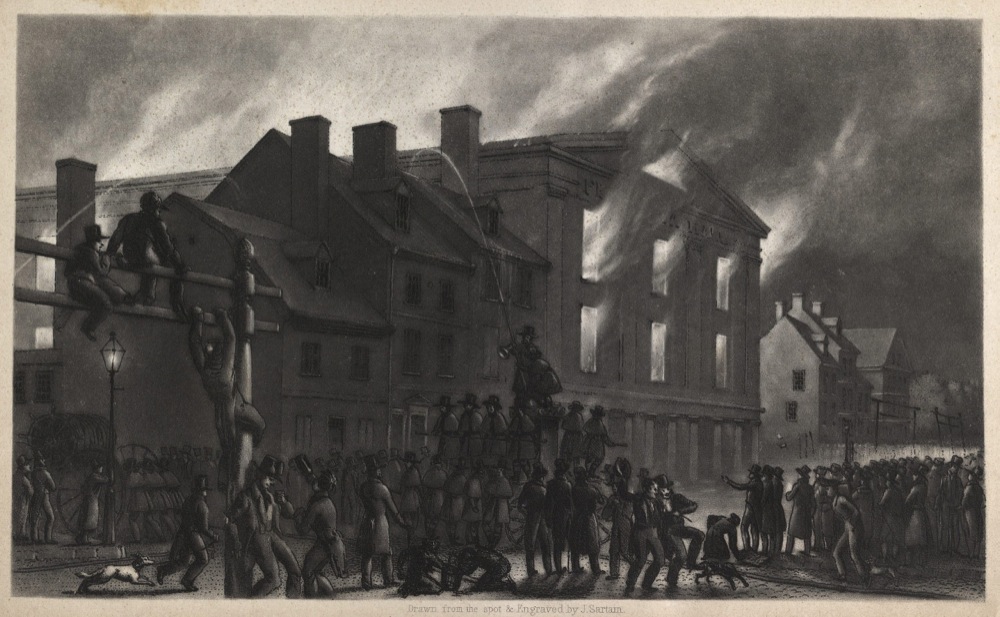

Attributed to Samuel Webb, this book has three plates – an illustration of Pennsylvania Hall, an illustration of the Hall in flames, and an illustration of the Hall after the fire. The Hall had been built from donations by members of the abolitionist community. However, its Board of Managers went out if its way to let it be known that the Hall was not only for the use of abolitionists. In its first two days, it was used as a meeting place for a women’s suffrage group. On the third day, it was used by the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, during which both women and freed slaves spoke. Women? Abolitionists? Women abolitionists? Freed slaves? The combination was apparently unacceptable to some. On the fourth night of the Hall’s existence, a mob surrounded it and set it on fire. Although a messenger was sent to the police for help, none was forthcoming. The topic of abolition was a particular point of contention with Philadelphian workers, who feared that their jobs would be in jeopardy when in competition with freed slaves.

Boston: J. Munroe and company, 1839

First edition

E449 C453

In this letter to a deacon in his church, William Channing attacked the institution of slavery but also the north’s compliance with the south in the existence of slavery in the United States. The pamphlet is a direct criticism of Henry Clay’s speech in the United States Senate on February 7, 1839. Channing lambasted Henry Clay for stating that slavery would remain in the United States forever. But he also compared slavery with war and contemplated his dread of civil war over the issue. A Virginian, Channing had a personal understanding of southern pride and the South’s willingness to fight in defense of states rights. In this way, he distanced himself from northern abolitionists, many of whom could not or would not believe that the anti-slavery struggle would result in war. He was attacked from both sides, but this pamphlet did much to prepare abolitionists for the long fight ahead. Remarks was so popular, it went through at eight printings in two years.

Emancipation was a response to Joseph John Gurney’s A Winter in the West Indies. Toward the end of his life, Channing became more direct in his anti-slavery admonitions. “…a people, upholding, or in any way giving countenance to slavery, contract guilt in proportion to the light which is thrown on the injustice and evils of the institution, and to the evidence of the benefits of Emancipation; and if so, then the weight of guilt on this nation is great, and increasing. Our fathers carried on slavery in much blindness. They lived and walked under the shadow of a dark and bloody past. But the darkness is gone….Slavery, from its birth to its last stage, is now brought to light. The wars, the sacked and burning villages, the kidnapping and murders of Africa, which begin this horrible history; the crowded hold, the chains, stench, suffocation, burning thirst, and agonies of the slave ship; the loathsome diseases and enormous waste of life in the middle passage; the wrongs and sufferings of the plantation, with its reign of terror and force, its unbridled lust, its violations of domestic rights and charities – these are all revealed. The crimes and woes of slavery come to us in moans and shrieks from the old world and the new, and from the ocean which divides them; and we are distinctly taught, that in no other calamity are such wrongs and miseries concentrated as in this… [T]o us, above all people, God has made known those eternal principles of freedom, justice and humanity, by which the full enormity of slavery may be comprehended. To shut our eyes against all this light; to shut our ears and hearts against these monitions of God, these pleadings of humanity; to stand forth, in this great conflict of good with evil, as the chief upholders of oppression; to array ourselves against the efforts of the Christian and civilized world for the extinction of this greatest wrong; to perpetuate it with obstinate madness where it exists, and to make new regions of the earth groan under its woes – this, surely, is a guilt which the justice of God cannot wink at, and on which insulted humanity, religion, and freedom call down fearful retribution.”

New York: Press of M. Day, 1840

First American edition

F1611 G96 1840

Joseph Gurney, a wealthy English aristocrat, philanthropist and Quaker, made several trips to North America, campaigning against slavery. He met with Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky and in a series of letters tried to convince him of the abolitionist cause. Gurney had visited the West Indies (the Leeward Islands, Cuba, and, most extensively, Jamaica) in 1840. His letters contrasted the condition of slaves in the southern United States with the freed slaves of Jamaica. He argued the benefits of freedom in economic as well as moral terms. He described hard-working ex-slaves, who retained the moral, religious and political values of their former masters. He used these observations to defend the state of freedom as natural, one in which “every man finds his own just level.” He used religion as an appeal, writing that it “spreads under the banner of freedom,” and, further, that freedom brought “quietness, order and peace.” All of which he said he witnessed in the slavery-free West Indian colonies. The first English edition of this work was printed in the same year under the title, A Winter in the West Indies.

London: John Murray, 1840

First edition

F1611 G963 1840

“It was a touching sight, coupled as it was with the recollection of the cruelties which many of them had once suffered; now, without exception, they seemed respectable and happy…my companion delivered to them a written message sent from the venerable Thomas Clarkson, now in extreme old age, to the peasantry of Jamaica, expressing his Christian love and sympathy, and advising the continuance of that patient and orderly conduct by which they have hitherto been so remarkably characterized. The message was received with respect, and called forth a warm response.”

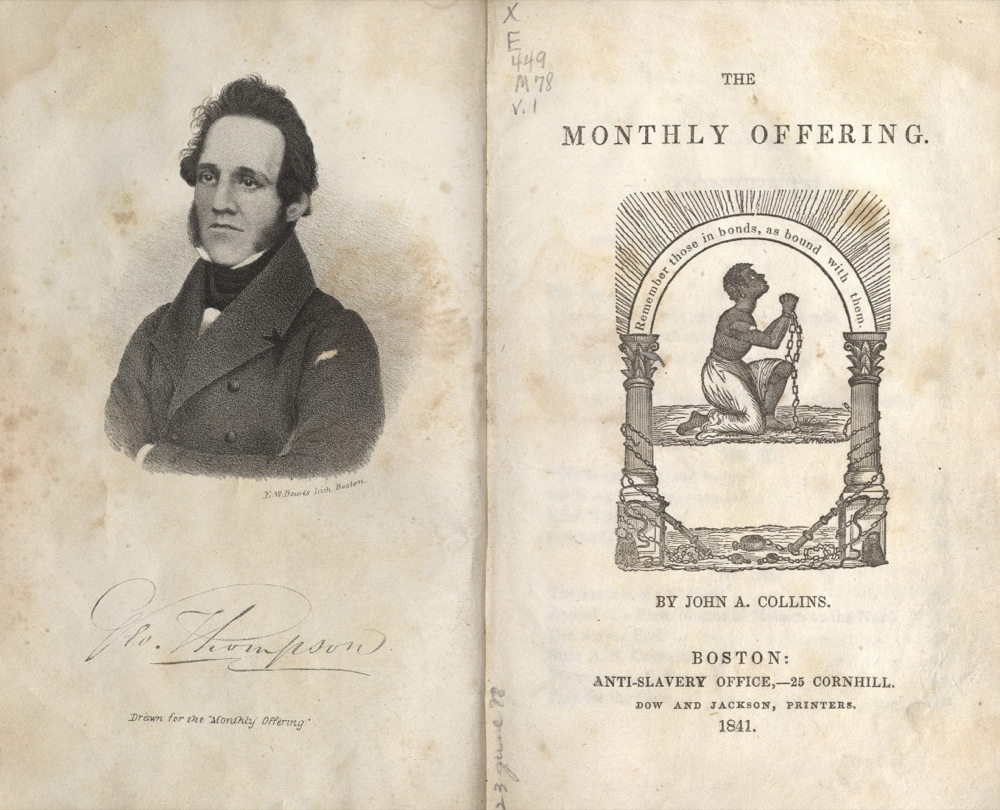

An abolitionist periodical published between July 1840 and December 1842, which included songs with music. No issues were published between March and August, 1841.

Boston: J. Munroe and company, 1844

First edition

E449 E54

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1844 speech, printed here, is one of the best of the anti-slavery speeches from the Transcendentalists. Until this speech, Emerson was not known for his public speaking. He accepted an invitation to speak to the Women’s Anti-Slavery Society on behalf of his wife, Lydian, a dedicated opponent of slavery. In this speech, Emerson forcefully proclaimed his support for abolition, revealing long-held private feelings on the subject. He gave the speech on the tenth anniversary of Britain’s emancipation of slaves in the West Indies, an act that had immense impact on the American abolitionists.

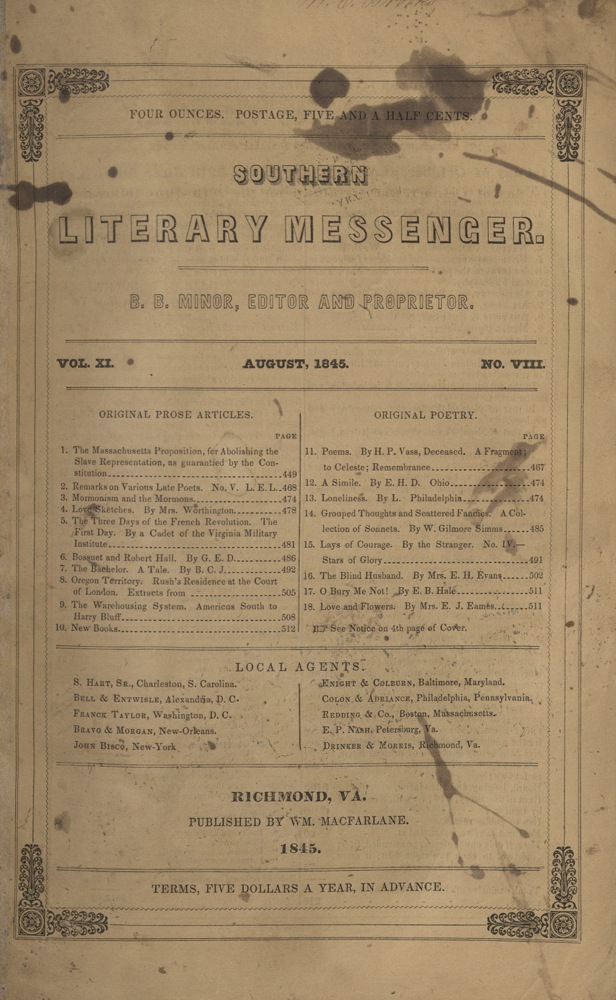

The Southern Literary Messenger was a periodical “devoted to Every Department of Literature and the Fine Arts.” Works included poetry, fiction, non-fiction, and reviews. Edgar Allen Poe served as a staff writer and critic for a short time in its early years. Most of its subscribers were northerners. By the 1850s, its tone had become decidedly political. George Frederick Holmes, a retired chair of classical languages at Richmond College in Virginia, wrote in an 1850 essay that, as Aristotle had said, the universality of slavery “proves the institution to be natural.” In an 1852 review, George Frederick Homes wrote of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “…unlike other works of the same type, its purpose is not amusement, but proselytism. The romance was formerly employed to divert the leisure, recreate the fancy, and quicken the sympathies of successive generation…never forgetting that its main object was to kindle and purify the imagination, while fanning into a livelier flame the slumbering charities of the human heart. But, in these late and evil days, the novel…has assumed to itself a more vulgar mission, incompatible with its essence and alien to its original design…mingling in the fumes…of political or polemical dissension…it has entered upon a sterner career…which requires us to question the visitant before admitting it to our confidence…” In another 1852 review, Harriett Beecher Stowe was assailed as having “volunteered officiously to intermeddle with things which concern her not – to libel and vilify a people from among whom have gone forth some of the noblest men that have adorned the race – to foment…unappeasable hatred between brethren of a common country, the joint heirs of that country’s glory – to sow…the seeds of strife and violence and all direful contentions.” By 1860, the editor had severed all ties with the northern literary establishment. The magazine’s northern readership decreased. In the war years, the magazine published battle accounts. The periodical stopped production in June 1864.

Boston: Press of T.R. Marvin, 1848

First edition

E420 W43 1848

“Now, if there has heretofore been such a North as I have described, a North strong in opinion and united in action against Slavery, if such a North has existed any where, it has existed ‘the Lord knows where,’ I do not. Why, on this very question of the admission of Texas, it may be said with truth, that the North let in Texas….Yes, had there not been votes from New England in favor of Texas, Texas would have been out to the day. Yes, if men from New England had been true, Texas would have been nothing but Texas still.”

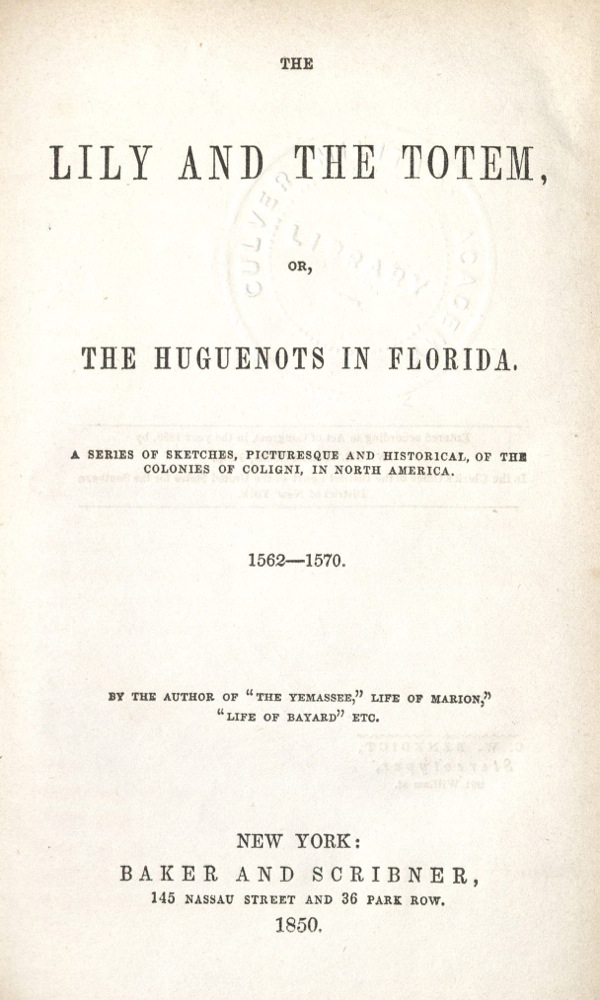

New York: Baker and Scribner, 1850

First edition

PS2848 L5 1850

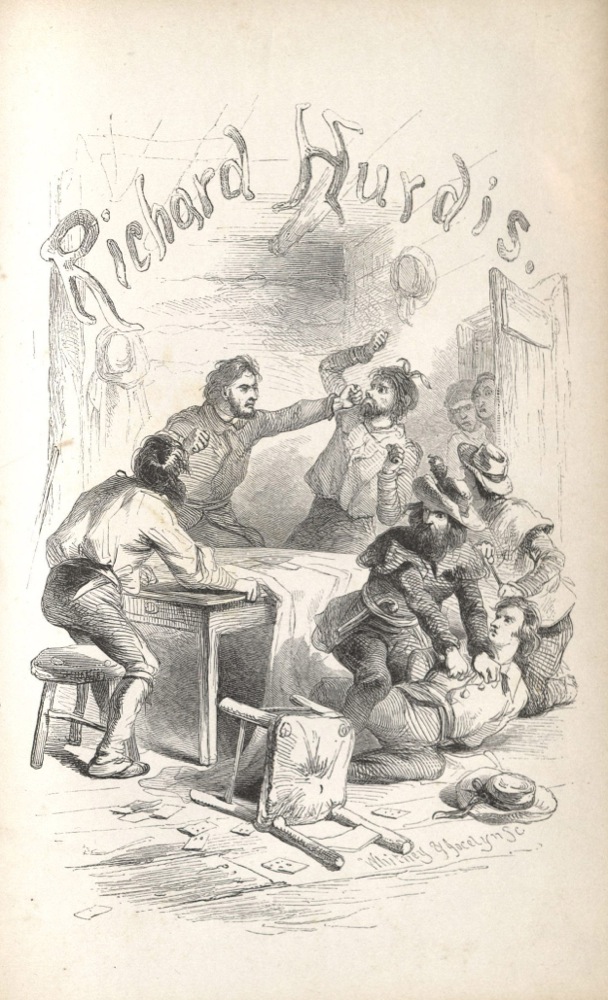

Edgar Allan Poe called William Gilmore Simms the best novelist in America. His novels of the south were very popular, his style compared to that of James Fenimore Cooper Today, he is remembered more for his opposition to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and his strong support for slavery. Educated as an attorney, Simms became a journalist, editor and part-owner of Charleston, South Carolina’s City Gazette. He abandoned this career when the paper folded in 1832.

Boston, MA: John P. Jewett & company. Jewett, Proctor & Worthington, 1852

First edition

PS2954 U5 E52a v.1-2

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was oil on the fires of the anti-slavery movement. On June 5, 1851, the first installment of Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared in the Washington anti-slavery paper, The National Era. At first there appeared to be little interest, but the story gained an ever-increasing audience as weekly installments followed. In book form it became a runaway sensation. In its first week of publication (March 20, 1852), ten thousand copies were sold. Within a year, three hundred thousand copies had been purchased. That the novel intensified the debate over the role of slavery is an understatement. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel gave the conflict an international audience. By 1860, Uncle Toms Cabin was in print in at least twenty languages. In southern states, Stowe became a hated woman. The novel has been described as exploding “like a bombshell,” its “social impact…on the United States…greater than that of any book before or since,” and “the book [that] precipitated the American Civil War.” Certainly no one expected that the long two-volume Uncle Tom’s Cabin, with the first African-American hero in American literature, and written by a woman, would become the most popular and influential novel in the United States of the nineteenth century.

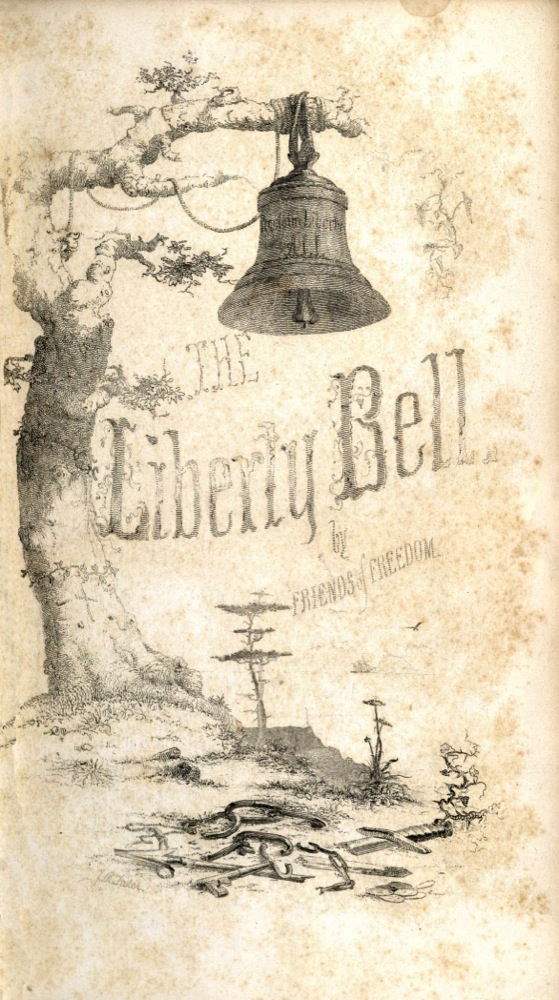

Boston: Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Fair, 1853

E449 L692 1853

Collections of prose and poetry such as this literary miscellany were very fashionable in the first half of the nineteenth century. Thousands were issued in the United States and, to a lesser extent Europe, during this period. Most of these so-called “gift-books” were neutral in tone, but others had a definite agenda. Organizations such as the Masons and the Sons of Temperance turned to these to promote their particular views. The Liberty Bell is one of seven anti-slavery gift-book publications distributed during this period and of those, the longest-lived. Published annually, it was edited by Marie Weston Chapman, to be sold or given away at the National Anti-Slavery Society, formed by Chapman and others. Chapman solicited material from well-known authors such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Russell Lowell. Elizabeth Barrett Browning contributed two pieces, both of which were published later in England. The authors donated their work. A later scholar criticized the literary standards of The Liberty Bell, describing it as “sentimental tales of horror.” The 1853 issue contains contributions by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Emily Dickinson’s confidant, and editor Marie Chapman.

A KEY TO UNCLE TOM’S CABIN; PRESENTING THE…

Boston: J.P. Jewett & co.; Cleveland, OH: Jewett, Proctor & Worthington;

London: Low and co., 1853

E449 S89592 1853

“To honor their weddings and funerals is, in some sort, acknowledging that they are human, and therefore they prize it. Hence we see the reason of the passionate attachment which often exists in a faithful slave to a good master. It is, in fact, a transfer of his identity to his master. A stern law and an unchristian public sentiment has taken away his birthright of humanity, erased his name from the catalogue of men, and made him an anomalous creature – neither man nor brute. When a kind master recognizes his humanity, and treats him as a humble companion and a friend, there is no end to the devotion and gratitude which he thus excites. He is to the slave a deliverer and a saviour from the curse which lies on his hapless race.”

Auburn: Alden, Beardsley, Rochester, Wanzer, Beardsley, 1854

Second series

E449 G851 1854

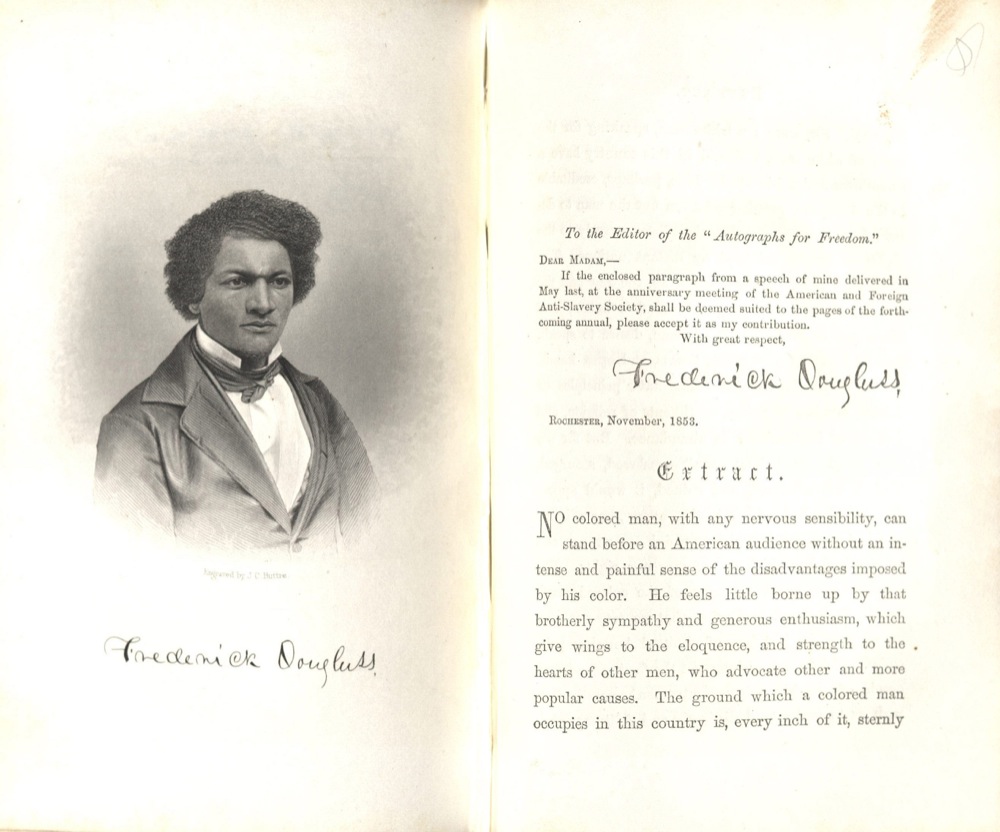

A collection of facsimile-signed articles, poems, and other writings by men and women prominent in the anti-slavery movement, published to assist Frederick Douglass in raising funds for his newspaper. One contribution is by James Monroe Whitfield, born into a free black family in New Hampshire in 1822. In a poem, he wrote, “How long, O gracious God! How long/Shall power lord it over right?” Other contributors include Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Horace Greeley, Harriett Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. In the preface to this second series (the first was published in 1853), editor Julia Griffiths wrote “…we greet thankfully those who have contributed of the wealth of their genius; the strength of their convictions; the ripeness of their judgment; their earnestness of purpose; the generous sympathies…ere the chains of the Slave shall be broken, and this country redeemed from the sin and the curse of Slavery.”

Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s life was spent actively agitating in the anti-slavery movement. He was a crusader for women’s rights and was one of the most influential voices of his time in the debate over women’s role in the public sphere. He is best known as Emily Dickinson’s confidant and literary advisor, corresponding with her for nearly twenty-five years. This is Higginson’s passionate sermon encouraging the people of Massachusetts to disobey the Fugitive Slave Law. He had been injured about ten days earlier trying to free a fugitive slave from U.S. Marshals who were returning the slave to the South. During the Civil War, Higginson served as a colonel in the first colored regiment of the Federal Army, fighting in the South Carolina and Florida campaigns.

Boston: J.P. Jewett; New York: Sheldon, Lamport & Blakeman, 1854

Third edition

E449 H641 1854

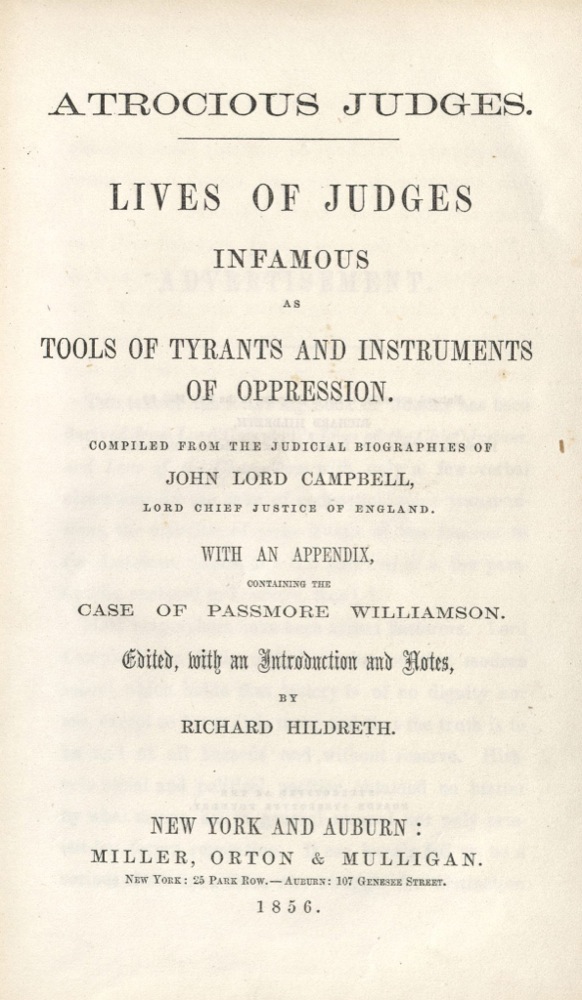

In 1834 Richard Hildreth visited the south for health reasons and there, particularly in Florida, saw examples of slavery that led him to write The Slave, in 1836, considered the first anti-slavery novel written by an American. In 1840 he published Despotism in America, in which he wrote of the harmful effects that slavery had on the economic and political development of the southern states. Despostism was well-received in abolitionist circles, remaining in print for more than twenty years, read by women such as Hildreth’s friend Marie Chapman and men who would become officers in the Union army. Between 1857 and 1860, Hildreth worked for the New-York Tribune and anonymously contributed several anti-slavery tracts for the newly-formed Republican Party.

First published in 1838, this novel of American expansion west into frontier territory was one of nearly two dozen novels William Gilmore Simms wrote about the American south. Considered one of the best writers of his day, Simms was also an admired historian. He wrote popular biographies of Revolutionary War heroes such as Nathaniel Greene. Simms responded to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in remarkable time, publishing an anti-Tom novel only months after the publication of Stowe’s blockbuster. Simms portrayed the white master and his wife as the benevolent caretakers of child-like Africans.

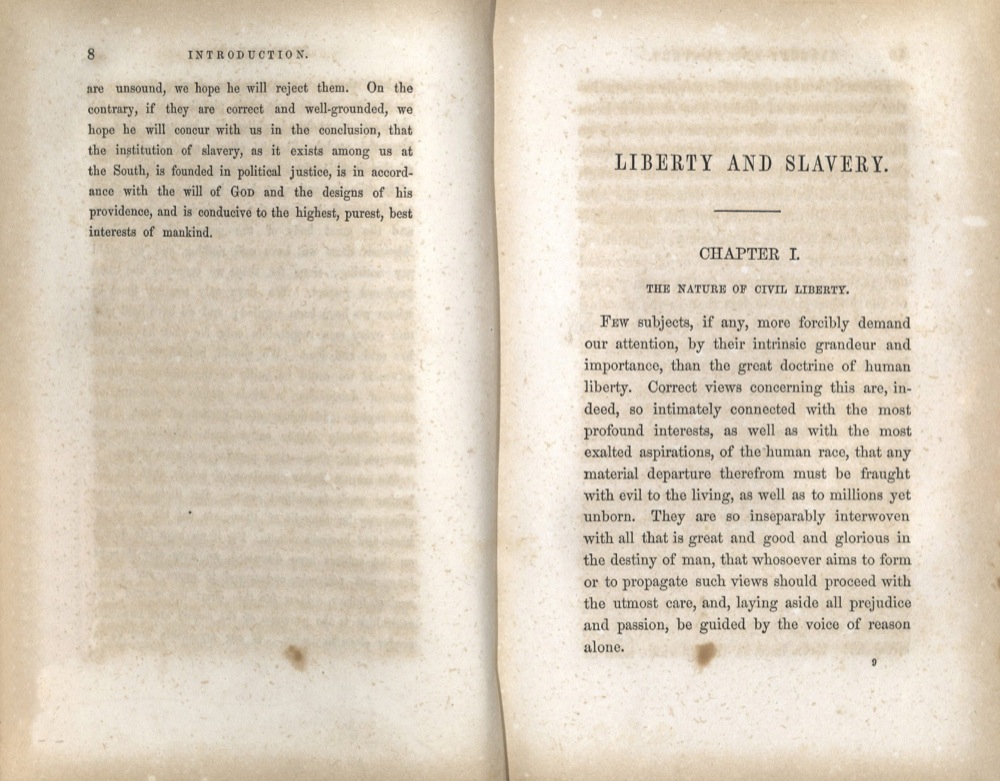

A fellow cadet of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee at West Point, Albert Bledsoe was an educator, attorney, clergyman, mathematician and defender of slavery and southern secession. His public championship of the south began with the publication of this work as a professor of mathematics at the University of Virginia. In it, he denied the existence of natural rights. Because slaves, like children, had no experience with freedom, the law should abridge a slave’s right to it. He argued that the Bible sanctioned slavery. Slavery, wrote Bledsoe, an institution recognized virtually everywhere in the ancient world, was part of scripture, old and new. Bledsoe cited both testaments on this point, in unrelenting detail.

New York and Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1856

First edition

KD7286 J8 C36 1856

Richard Hildreth added his own accounts to this collection to highlight judiciary abuses in support of slavery. American judges in both federal and state courts briskly enforced the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. In one instance, Hildreth wrote of the court vs. Passmore Williamson. Williamson was an abolitionist from Pennsylvania. While working for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, he helped a fugitive slave and her two children escape from their master while traveling. Williamson directed the “escape” using force. For his part in the debacle, Williamson was convicted of contempt of court by Pennsylvania District Court judge John Kane and served time in prison. The northern press spread the story throughout the country.

Boston: Benjamin H. Greene, 1856

First edition

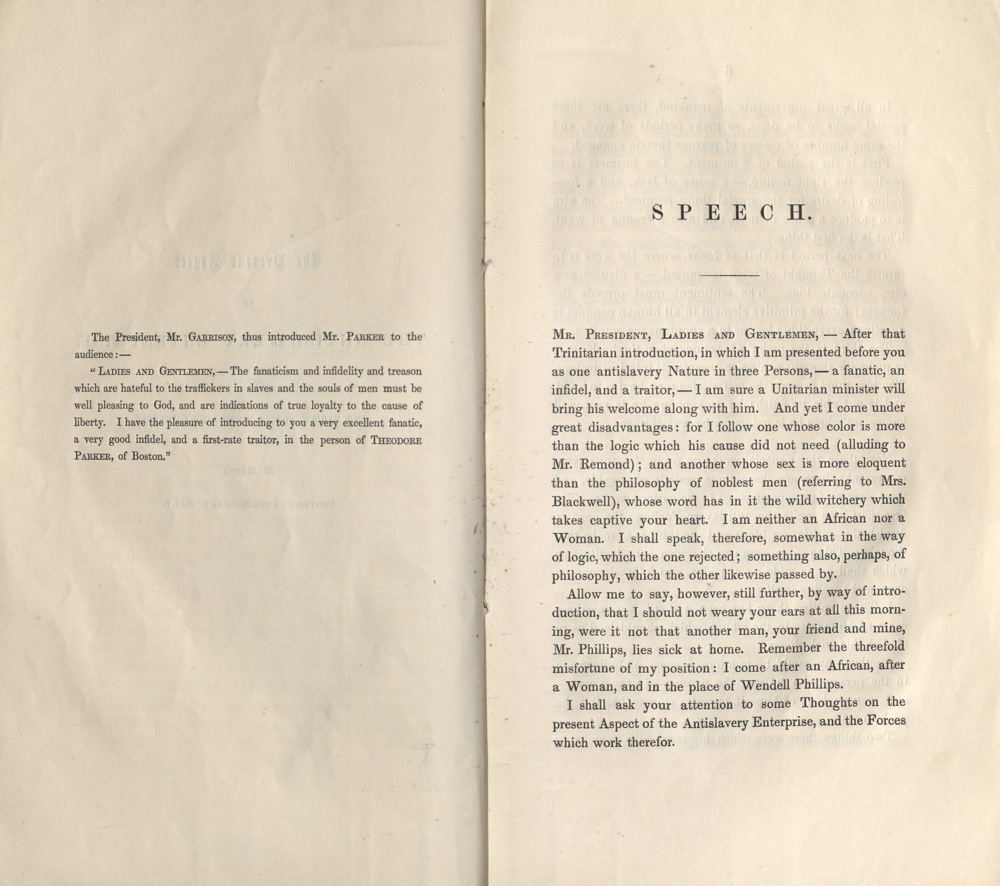

E449 P29

Unitarian preacher, lecturer, writer, reformer and abolitionist, Theodore Parker pronounced slavery as the greatest obstacle to democracy. He led the Boston opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. His actions set him apart from other Boston Unitarian ministers, who refused to oppose the legislation and supported it as a necessary concession in order to save the Union. He joined a clandestine committee that helped finance and arm John Brown’s attempt at a slave insurrection in Virginia.

Boston: J.P. Jewett; Cleveland, OH: H.P.B Jewett, 1858

E444 H52 1858

Josiah Henson, a slave, escaped to Canada in 1830 and founded a settlement there for other fugitive slaves. His autobiography, first printed in 1849, received little attention at the time. In 1853, Harriet Beecher Stowe mentioned it in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She wrote the introduction to this expanded 1858 edition. Stowe suggested that she used Josiah Henson as an inspiration for the title character of her bestseller. The book was reprinted in 1876 and 1878.

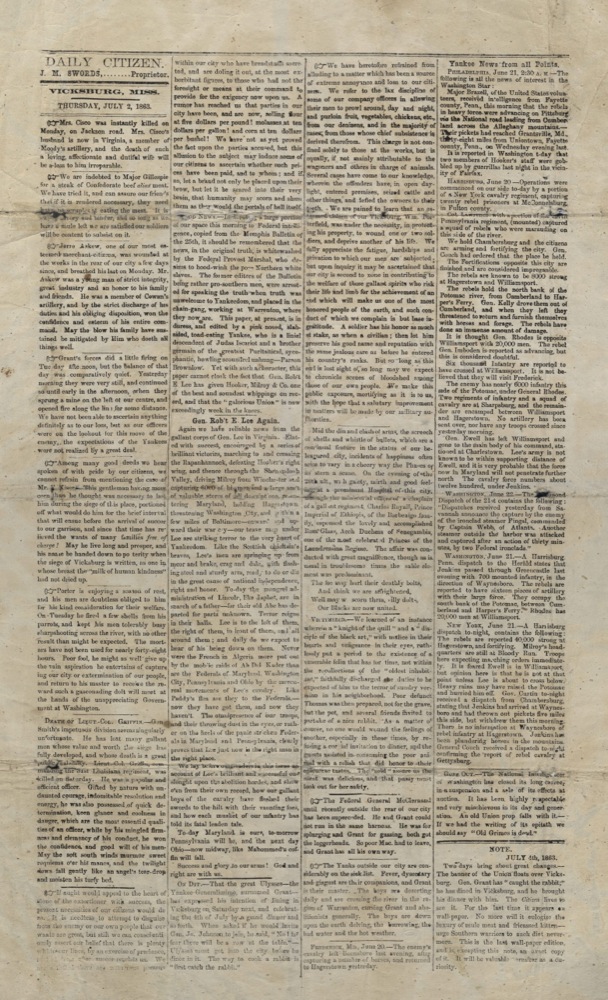

DAILY CITIZEN

Vicksburg, MI: J.M. Swords, 1859

AN2 M48 D35 1864: July 4

The Daily Citizen, printed in Vicksburg, Mississippi beginning in 1859 ceased publication in 1864. Wartime is always disruptive, not the least for printers. In the midst of the American Civil War issues of this newspaper were printed on the back of wallpaper between June 18th and July 2, 1863. This particular issue has a note on it dated July 4th, 1863 saying “For last time it appears on wall-paper.” The issue was bought by an Iowa soldier, who carried it to Chickamauga, where he was killed. It was returned to his family with other personal effects after his death and remained with the family until 1959 when it was given by descendant Bertha Goodrich Holbrook of Price, Utah to Dr. Floyd O’Neill. Ms. Holbrook, a school teacher, had been given the paper by her father who, in turn, had received it from a relative. Bertha Holbrook lived and taught in Carbon County, Utah for many years. She was a graduate of Drake University and had a lively interest in history. After many spirited discussions about American history, she gave the item to Dr. O’Neill, her neighbor, as a reminder of their mutual interests and friendship. University of Utah copy gift of Dr. Floyd O’Neill, 2003.

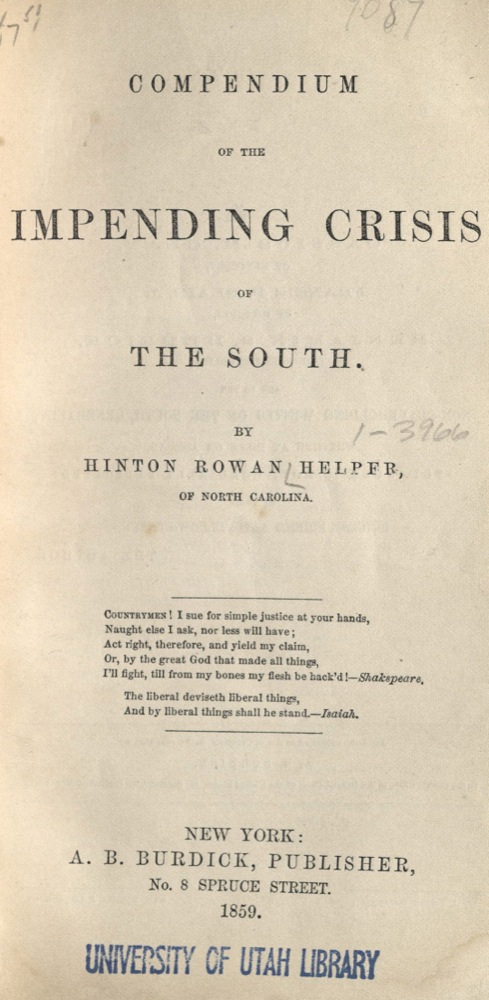

New York: A.B. Burdick, 1859

First edition

E449 H481 1859

Hinton Rowan Helper was born in North Carolina, the son of a small slave-owning farmer. In 1857, he published The Impending Crisis of the South, an analysis of the economic downfalls of the institution of slavery for the south. For his argument, Helper used statistics – there was nothing sentimental about it. He did not address the conditions of slavery upon slaves, but rather argued that slavery hurt the economic prospects of non-slaveholders and was an impediment to economic growth in the south. Helper wrote on behalf of the majority of southern whites, oppressed, he contended, by a small but politically dominant slave-owning aristocracy. In 1857, the book was barely noticed. In 1859 it was printed in this abridged form and was latched onto by northern abolitionists. Between 1857 and 1861, 150,000 copies were printed. The Republican Party distributed it as campaign literature in 1860. In the south, distribution and possession of the work was banned, seized copies were burned.

“I believe the most that the people – the voters – of this country desire, in reference to the question of slavery, is, to know, from an authentic source, what the framers of the Constitution meant to do with it; what relation they meant the government should hold to the institution, if any; and that, knowing this, regardless of the selfishness and fanaticism of politicians, north or south, east or west, they will steadily pursue the path marked out by their fathers, and perpetuate the principles of Constitutional liberty with every energy and effort in their power…It is not I who speak, but rather the voice of the immortal dead, a voice from the tombs of those great spirits, who, through the perils of war and revolution, established a government, the freest and the happiest on earth, and bequeathed it to us. Let us heed their admonitions, emulate their virtues, and profit by their examples.”

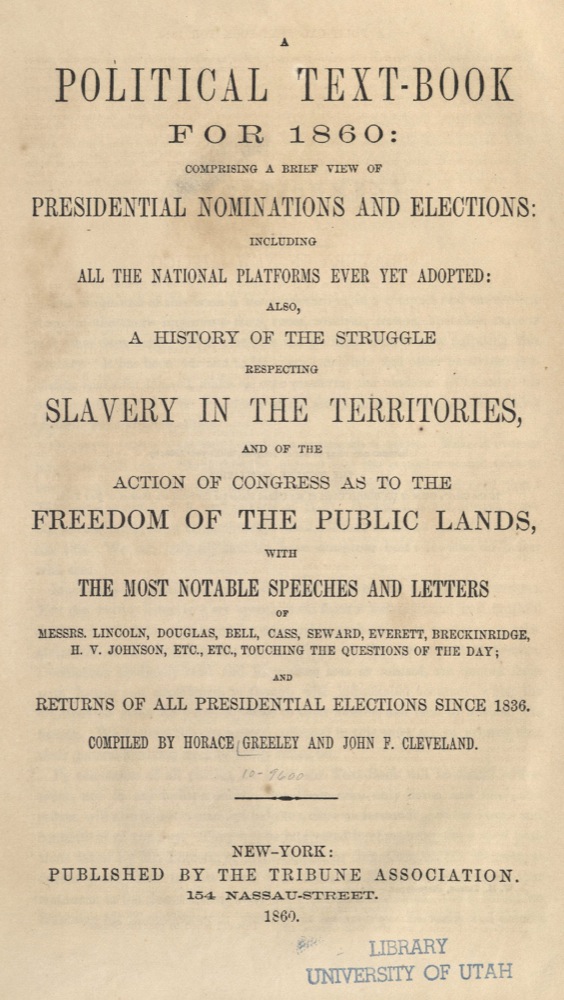

New-York: Tribune Association, 1860

First edition

E440 G79 1860

Horace Greeley, born in New Hampshire, apprenticed as a printer in Vermont and then worked as a journeyman printer in Pennsylvania and New York. He began his publishing career in 1833 with the Morning Post. He published the New Yorker between 1834 and 1841. He founded the influential New-York Tribune in 1841, remaining editor until his death. The paper would quickly become the most widely circulated daily in the country, particularly in the north. He served the Whig party as a representative from 1848 to 1849 and as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1860. In 1861, he ran an unsuccessful candidacy for Senator. After the Civil War he advocated universal amnesty and, in 1867, offered bail for Jefferson Davis. Even so, Greeley and his paper were strong opponents of slavery before and throughout the war. The paper and Greeley were instrumental in keeping the issue of slavery part of public dialogue.

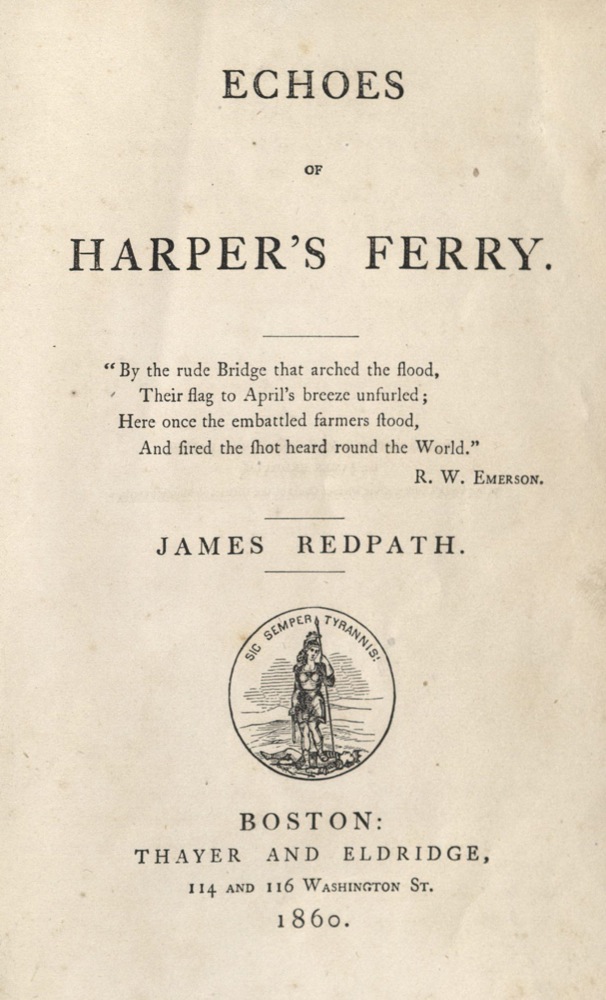

Born in England, James Redpath moved with his family to Michigan in 1849. His desire to become a printer was superseded by his reformist activities. He spent his life fighting for abolition, civil rights, Irish rights, and suffrage. Redpath began his career writing impassioned anti-slavery tracts under the pseudonym, “Berwick.” At the age of nineteen he was discovered by Horace Greeley, who convinced him to move to New York and write for the New-York Tribune. Redpath visited the south three times between 1854 and 1857, each trip solidifying his stance against slavery. Redpath supported John Brown at a time when most abolitionists did not support Brown’s ideas or activities. He wrote several tracts defending Brown. This commemorative collection of anti-slavery articles and poems for Brown, edited by Redpath, included contributions from Henry Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Louisa May Alcott, at the request of Redpath, contributed “With a Rose, That Bloomed on the Day of John Brown’s Martyrdom,” previously published in an issue of the Liberator: “Then blossomed forth a grander flower/In the wilderness of wrong./Untouched by slavery’s bitter frost,/A soul devout and strong.”

HARPER’S WEEKLY, A JOURNAL OF CIVILIZATION

New York City, New York

Volume 5

February 2, 1861

February 2, 1861

AP2 H32 v.5 1861

“The Dream of a Secessionist. Washington and Valley Forge.”

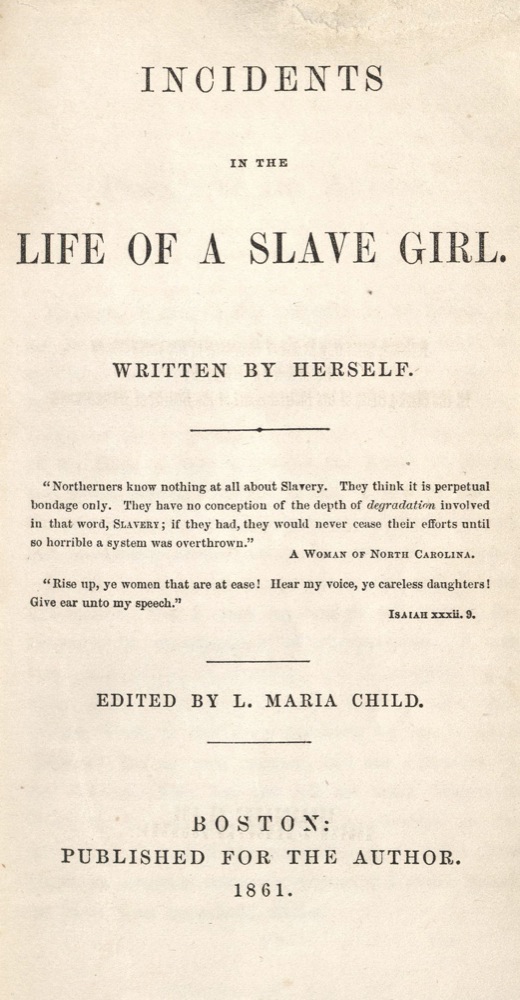

Boston: Published for the author, 1861

First edition

E444 J17 A3 1861

A slave in North Carolina, Harriet Jacobs escaped from her third master. In 1842, she made her way to New York, where she became a nanny and joined the anti-slavery movement. She wrote this memoir under the pseudonym "Linda Brent." Jacobs began writing her story in the 1850s. The style and structure is very much like that of nineteenth century sentimental novels. Parts of the work were published in serial form in Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune. The brutal and sexual nature of the events described was deemed too shocking for newspaper readership and the serialization was stopped. The complete work was published in book form in 1861, after some struggle to find a publisher. As an attempt to legitimize (and market) the book, Harriet Beecher Stowe was asked to write the preface. She turned down this request. Nevertheless, the memoir was well-received and quickly used, as were many other slave narratives, as documentation for the anti-slavery movement. However, the authorship was questioned. Many suggested that the entire story was a fabrication, published only to support abolition. Harriet Jacobs, however, was a real person and later research has proved that at least most of her story was factual.

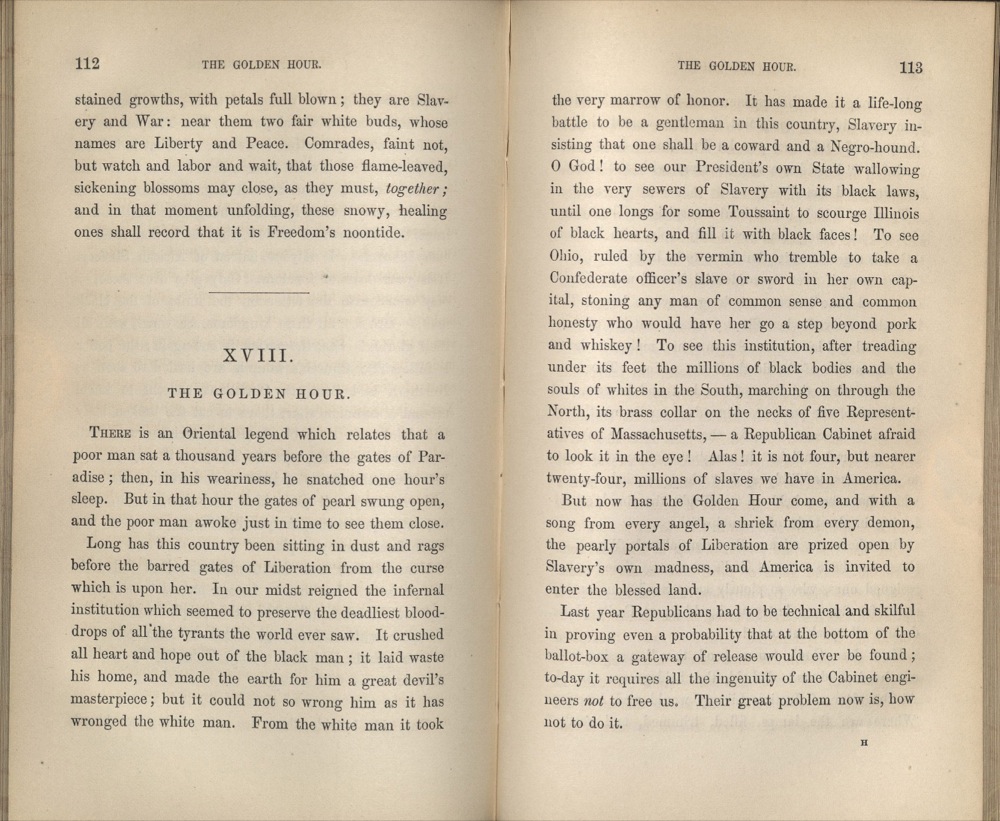

Son of a long established, wealthy Virginia family, Moncure Conway’s opposition to slavery derived from his mother’s influence and from boyhood observation. His father and brothers were staunchly pro-slavery. In 1852, while attending Harvard Divinity School, he met and came under the influence of Ralph Waldo Emerson. The two would remain lifelong friends. Conway also befriended Henry Thoreau, Bronson Alcott, Theodore Parker, and other abolitionists. However, his advocacy of a peaceful separation of northern and southern states as a solution to the slavery problem lost him credibility within abolitionist circles. The Golden Hour was the second in as many years of two passionate pleas for emancipation. In it, addressing President Abraham Lincoln directly, Conway argued that emancipation would cripple the Confederacy’s war effort and hasten peace.

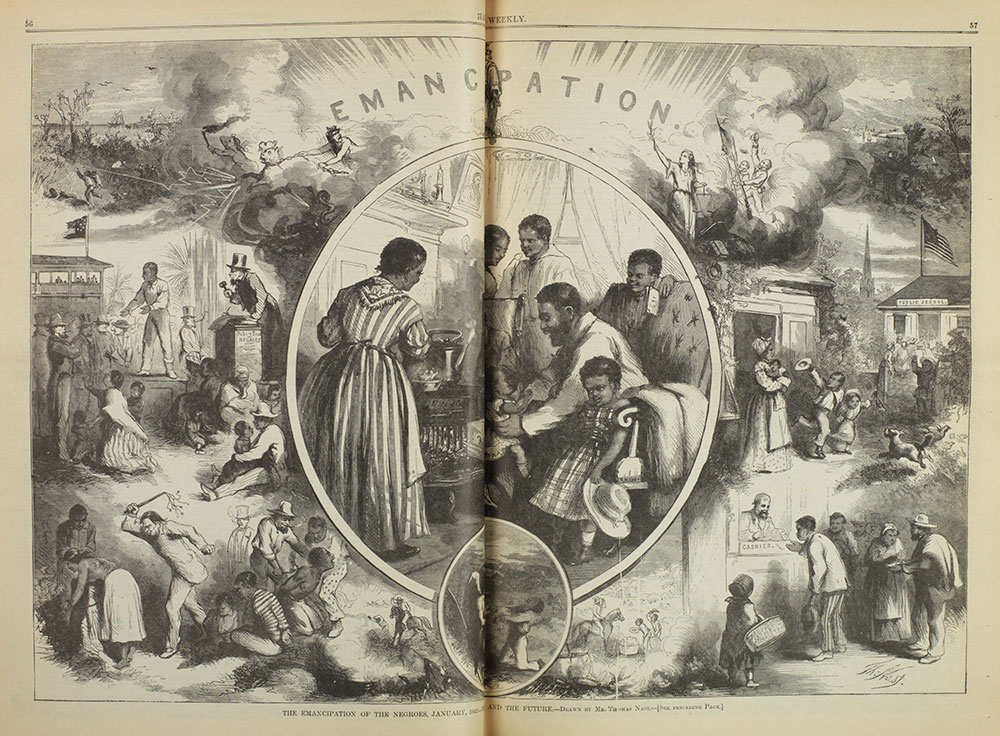

HARPER’S WEEKLY, A JOURNAL OF CIVILIZATION

New York City, New York

Volume 7

January 24, 1863

January 24, 1863

AP2 H32 v.7 1863

“The Emancipation of the Negroes, January, 1863 – The Past and the Future.”

Charles Wells Russell was a prominent Virginian Confederate politician. After the war he wrote, “Then, while he lingered yet a little longer, conversation turned upon the desolation of Virginia and the suffering of her people. A large portion of the State was already ravaged and devastated. The flower of her youth and manhood had been cut down by thousands. From the first to the last hour of the war the blood of the State flowed in torrents, and in all her borders it seemed that nothing could stand erect under the incessant storm of war but her unconquerable spirit.” Thirty percent of all Southern white males aged 18–40 died in the American Civil War. Ten percent of all Northern males aged 20- 45 died. University of Utah copy is from the personal library of President John R. Park, a gift to the University.

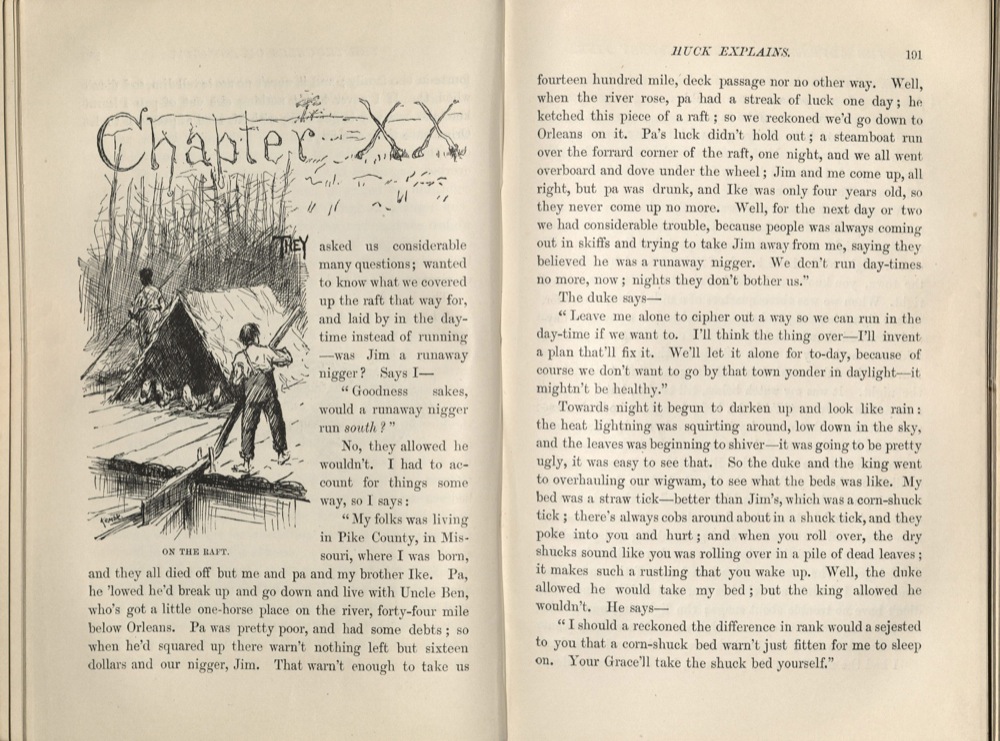

London: Chatto & Windus, 1884

First English edition

PS1305 A1 1884

When it was published, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was derided by critics for, among other things, immorality, coarseness, and profanity. The story is still banned by libraries and schools in the United States. Nonetheless, it is one of the defining novels of American literature. Ernest Hemingway said of it, “All modern literature comes from [it]. It’s the best book we’ve had…There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.” In it, Samuel Clemons took a scathing view of slavery and cast a satirical eye over the antebellum south. It was published in England a few months before the American edition was published. Publisher’s advertisements in the back of this copy are dated October 1884. This copy is thread-sewn, one of two states of gatherings for the first English edition. University of Utah copy bound in original gilt-and black-stamped red pictorial cloth.