Botanical Rarities

Inspiring myth, legend, fairy tale, and poetry...

Checklist for Botanical Rarities

Curated by Luise Poulton, 2003

Digital Exhibition produced by Lyuba Basin, 2020

Botanical Rarities

Botanical Rarities

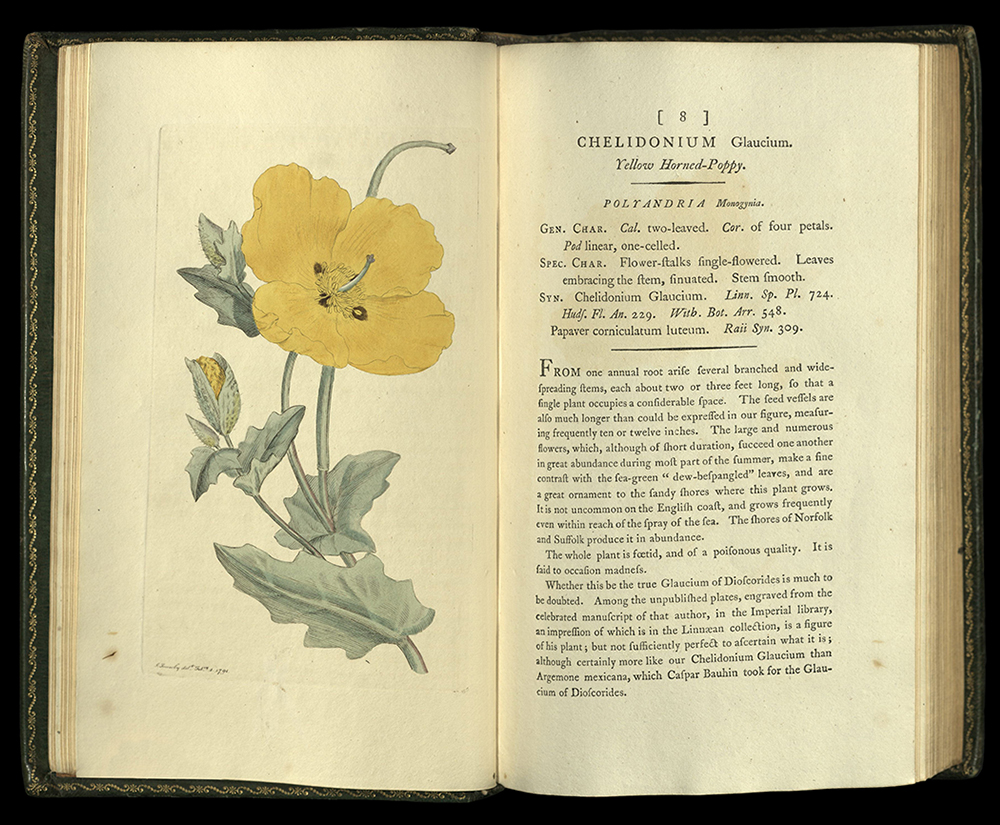

The first Mesopotamian writings on clay tablets included information about plants. Ancient pharmacopoeias recorded plants for medicinal uses. From Dioskorides’ work on pharmacology during the classical Greek period through the nineteenth century, plants and the study of plants, or botany, has intrigued and inspired humankind. The work of Dioskorides, which described more than five hundred plants, was the authority on plants in Western Europe for nearly sixteen centuries, although studies from the Arab world became known as early as the tenth century. New knowledge was gained from travelers, including Marco Polo; observations brought back from the Crusades; and later explorations into other hemispheres. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a system to identify the great variety of plant species began to be developed. From the beginnings of civilization plants have fed, clothed, sheltered, and healed. They have inspired myth, legend, fairy tale, and poetry. And they have always pleased the eye in the ground and between the covers of books.

Botany became a recognized field of study as early as the third century BCE. The Greek philosopher Aristotle studied plants, although nothing remains of his writings on them. Two works by his student Theophrastus have survived, however. Theophrastus discussed plant anatomy, classification, and medicinal uses. The focus on plants as medicine neither began nor ended with the ancient Greeks. The first pharmacopoeia prescribing medicine made from plants was written nearly three thousand years before Aristotle was born. The earliest civilizations of Sumer, Egypt, and China all left records of plants, their descriptions, and their various uses based on traditions begun long before the written word. Herbals were so popular in medieval and renaissance Europe that they were among the first books printed after the introduction of the printing press in 1450 and are intimately connected to the history of printing itself. The earliest printed illustrations were woodcuts copied from earlier manuscripts, whose illuminations had been, over a thousand years, codified into an orthodoxy that rarely mimicked nature. Exceptions to this, a slow move toward naturalism, began with the luxurious fifteenth century Books of Hours.

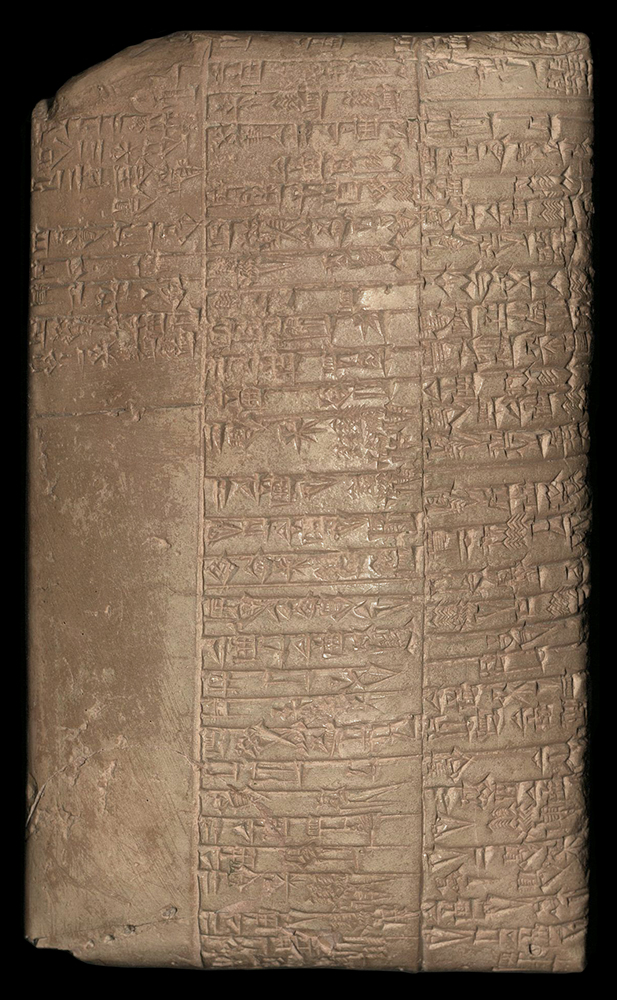

FACSIMILE PHARMACOPEIA

circa 2100 BCE

Writing began somewhere during the third and second millennia BCE in Sumer between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Mesopotamian writings included myths, epic tales, hymns, lamentations, proverbs, and fables. The Sumerians also recorded history; business and legal documents; mathematics; zoological, mineralogical, and botanical studies. The writings were inscribed on tablets made of clay taken from the banks of the rivers, mixed with straw, and formed into various shapes. A sharp stylus was used to press marks into the damp clay. The forms were then dried in the sun or baked in hot ovens.

This facsimile is of the oldest medical text in human recorded history, written sometime toward the end of the third millennium BCE by an unknown Sumerian physician. It is a collection of his prescriptions. Most of his medicines came from the botanical world. He used – among other things – myrtle, thyme, pears, figs, dates, seeds, roots, branches, barks, and gums. There is no mention of magic, incantations, gods, or demons.

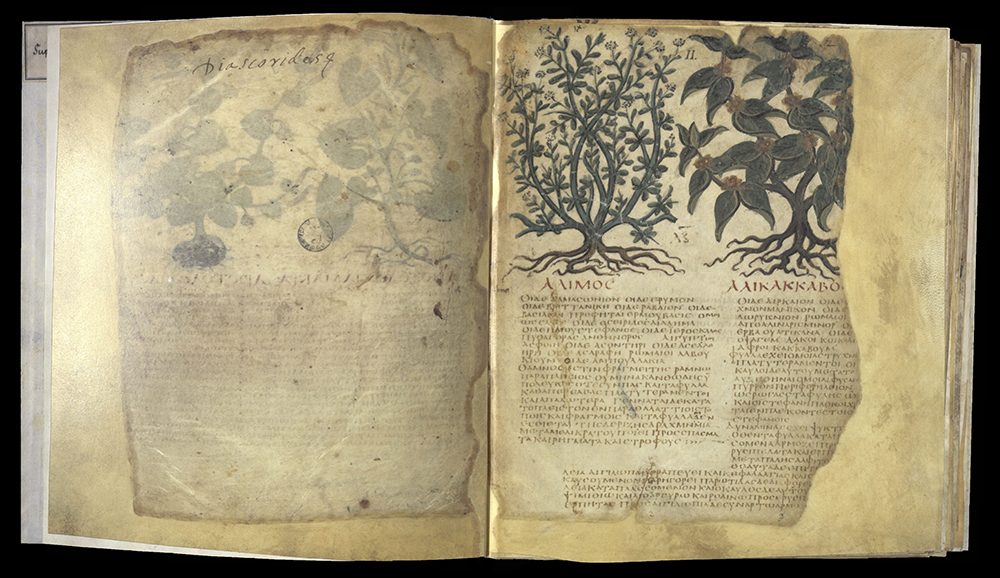

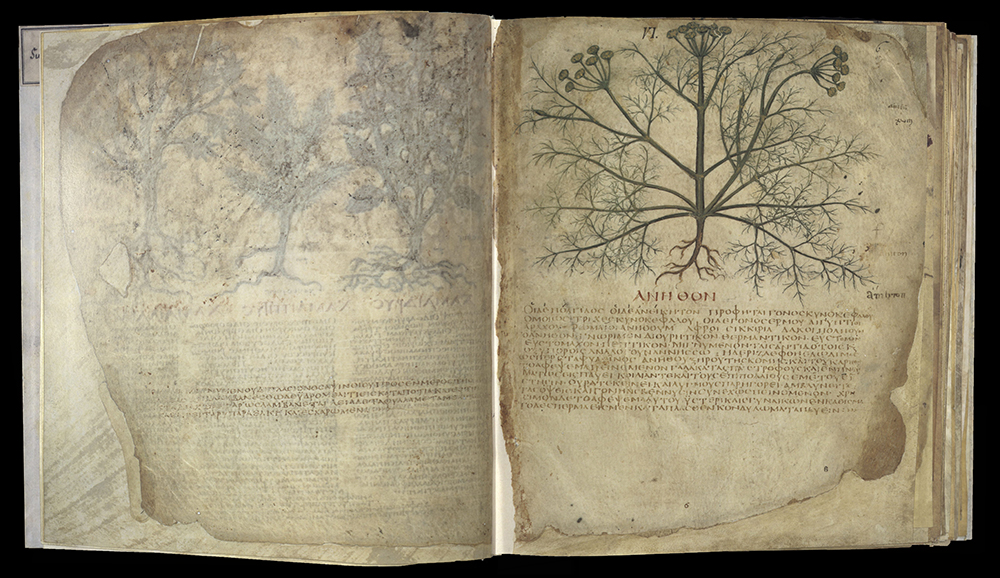

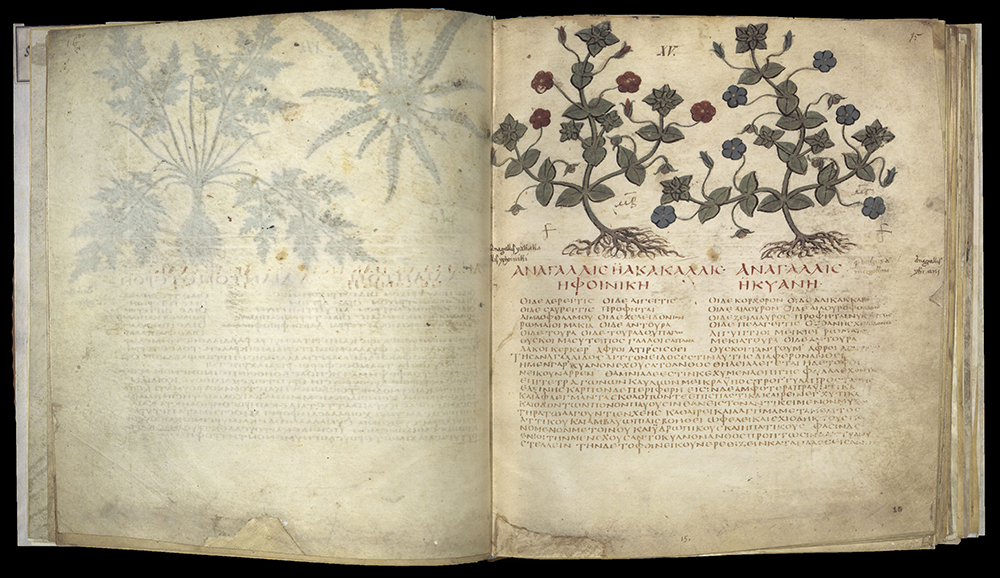

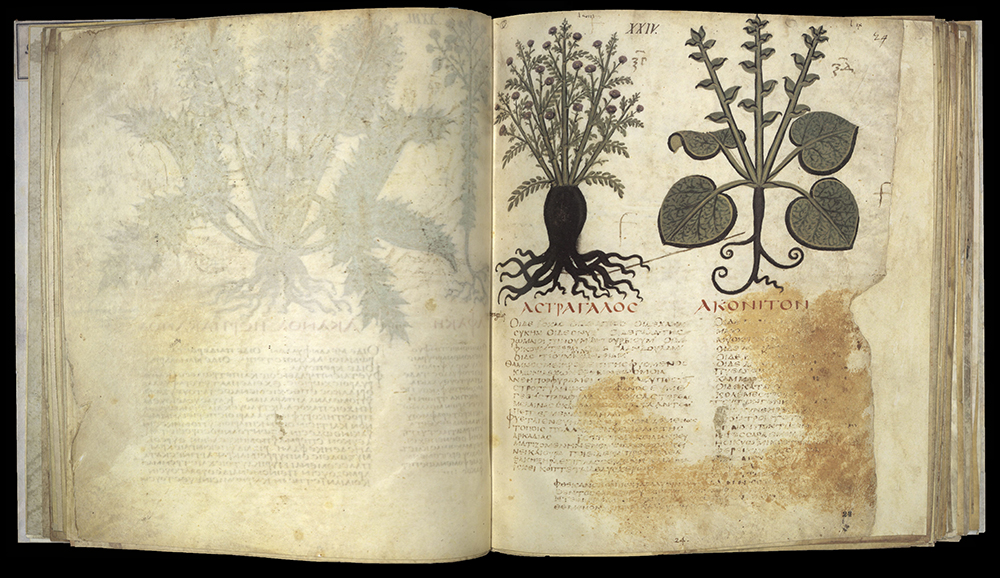

Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbos

Roma: Salerno, 1988

R126 D56 1988

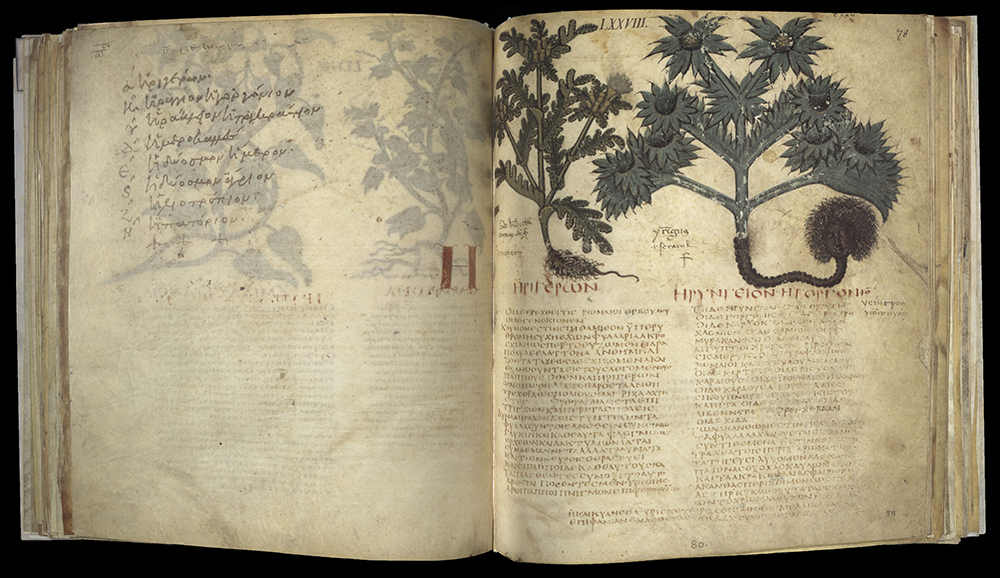

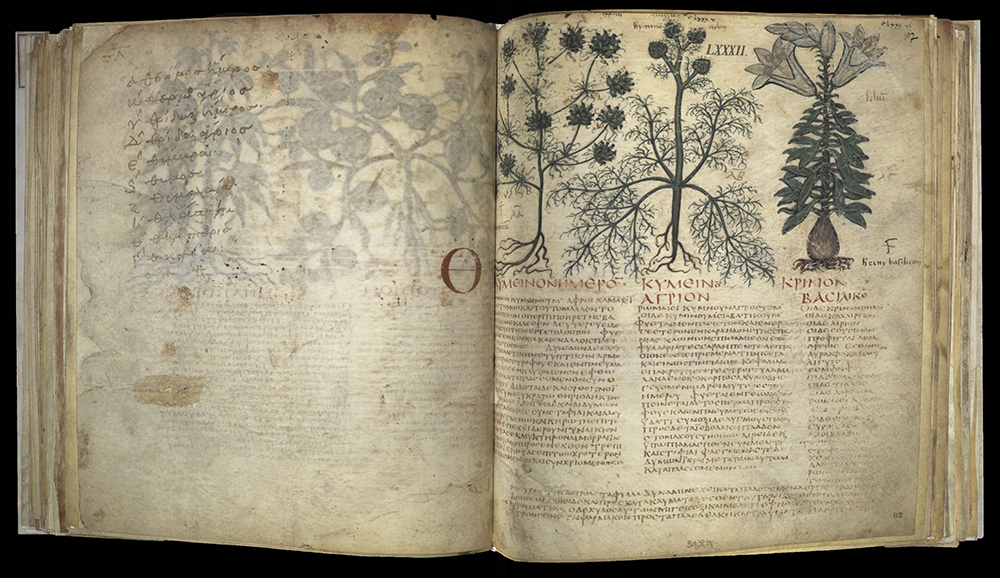

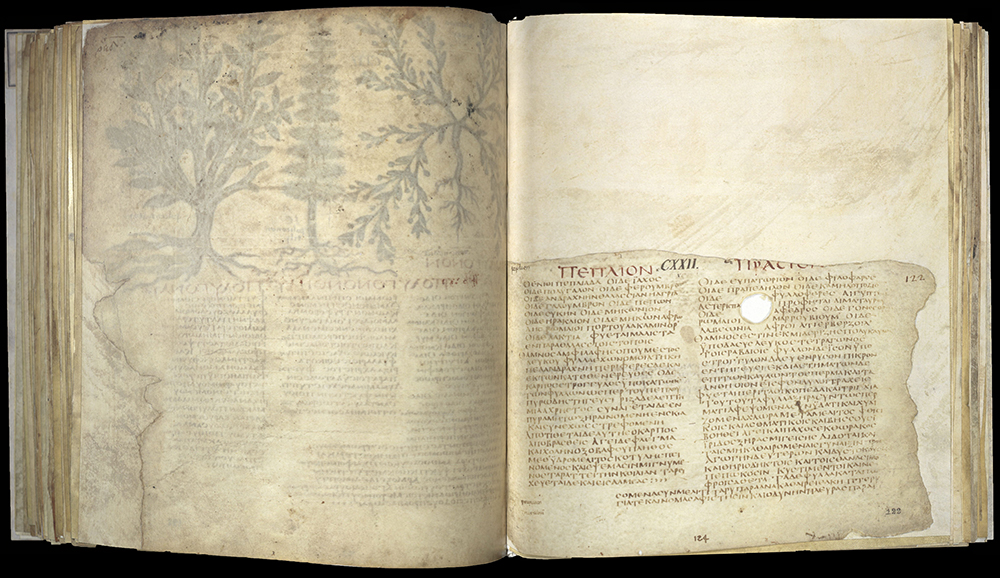

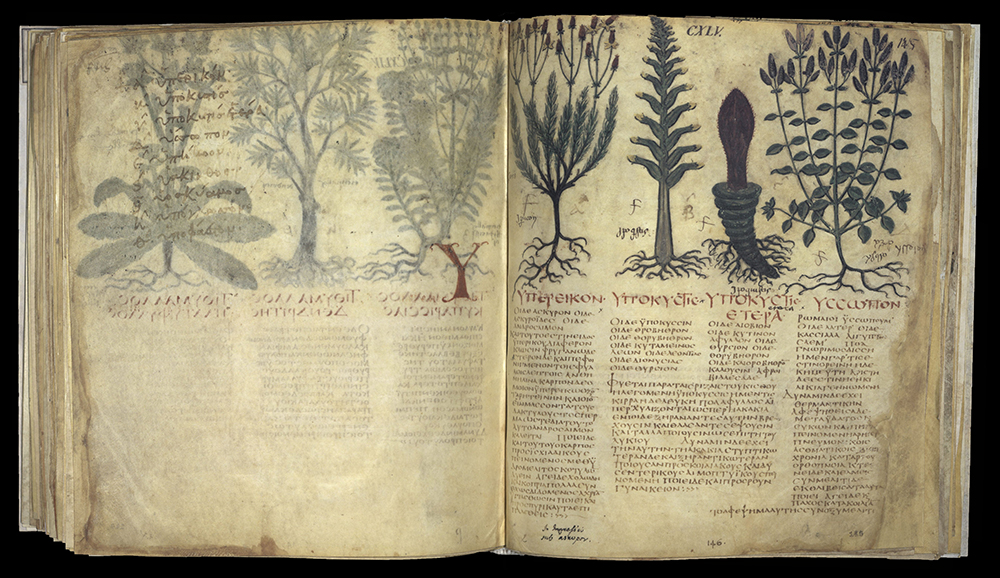

Probably produced in Italy in the seventh century, this herbal manual has more than four hundred illustrations. The manuscript is one of the oldest surviving in the tradition of Materia medica, a pharmacological treatise written by the Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides in the first century CE.

Describing foliage, stems, and roots, Dioscorides emphasized the usefulness of plants. Dioscorides claimed to have traveled widely (possibly with Nero’s army) and admitted that his work was a compilation to which he had added his own observations. His work was used by the medieval world for centuries. It was translated into Latin in the sixth century and into Hebrew, Syriac, Farsi, and Arabic by the ninth century. It was an important work in the medical knowledge of the Islamic world.

De Materia medica remained the final authority on pharmacology for more than sixteen centuries. It was printed in Latin as early as 1478 and in Greek as early as 1499. Between 1555 and 1752 at least twelve editions in Spanish were printed, an equal number in Italian, three in French between 1553 and 1580, and in German in 1546, 1610, and 1614. The editions were printed with numerous annotations and commentaries.

FACSIMILE THERIAKA Y ALEXIPHARMAKA DE NICANDRO

Nicander of Colophon

Barcelona: Moleiro, 1997

QP941 N53 1997

This manuscript, produced in the tenth century during the Byzantine Renaissance, is a copy of the oldest Greek texts relating to toxicology. It is the only extant illuminated manuscript of Nicander’s poems. Doctor, poet, and grammarian, Nicander of Colophon lived in the second century BCE at the court of Atala III, King of Pergamum, and future home of Galen.

Theriaka deals with the bites of wild animals, poisonous snakes, and insects. The Alexipharmaka deals with other poisons of vegetable and mineral origin as well as the precautions to be taken and appropriate curative remedies. The formulas often consist of fifty to sixty substances. These substances were increased by Mithradites, who added opium and aromatic herbs. Later, Criton, Trajan’s doctor, added more to the formulas. Finally, Andromachus, Nero’s doctor, after making his own additions to the formulas, listed the seventy-one definitive substances in a poem in order to protect the formulas from any further alteration. The formulas were used well into the nineteenth century.

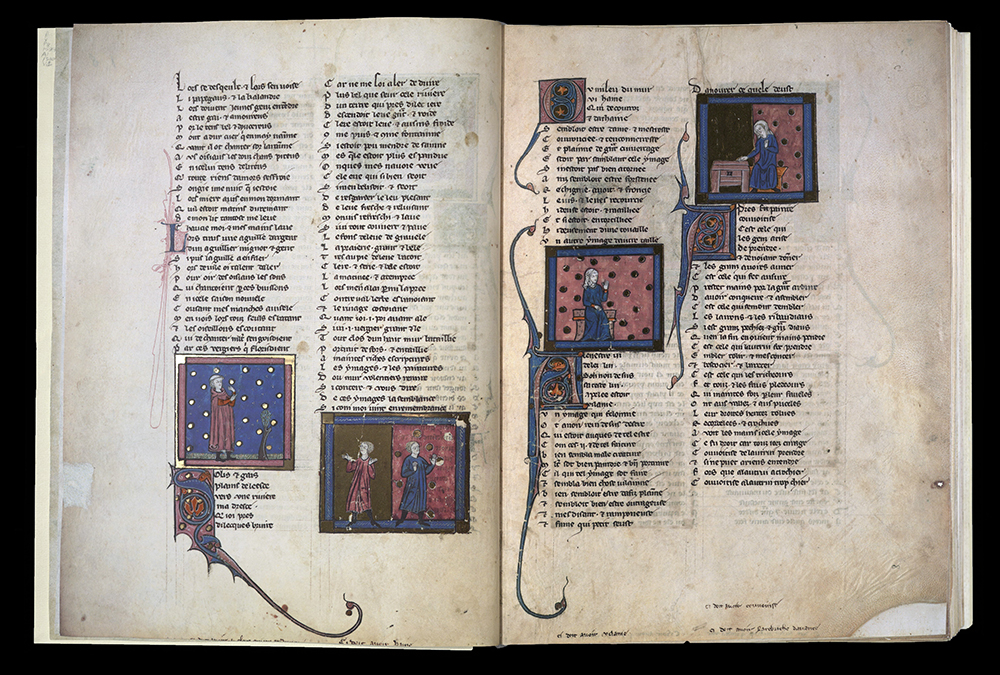

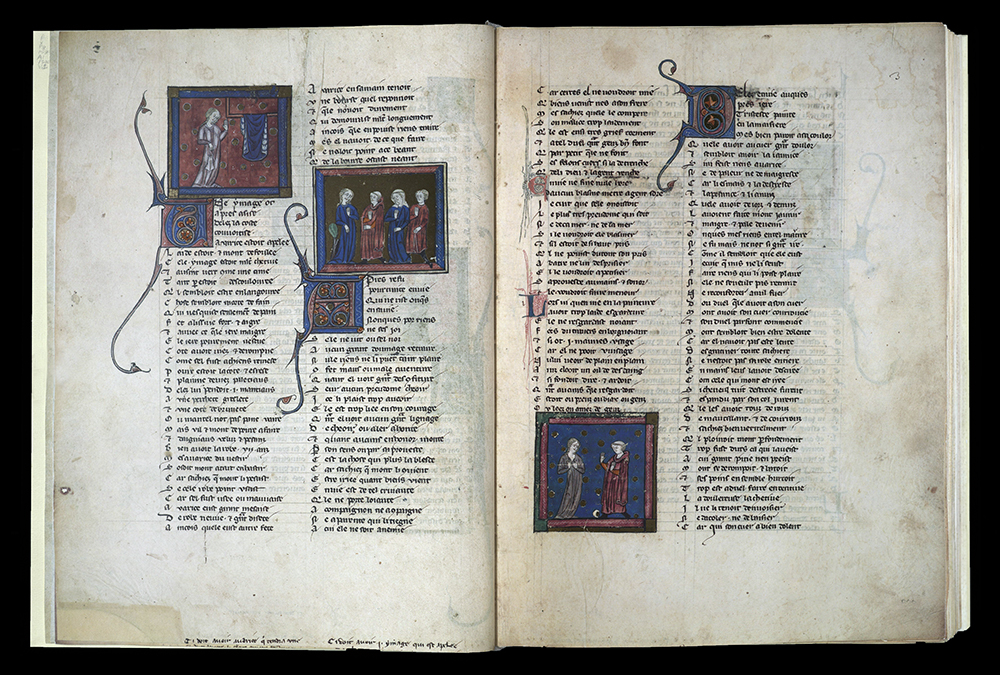

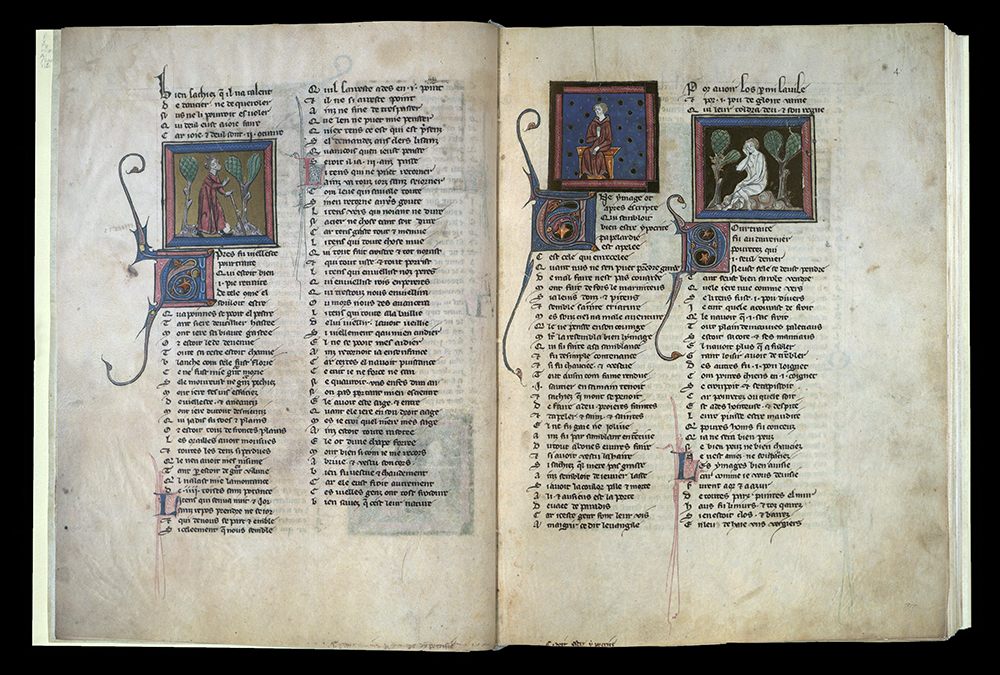

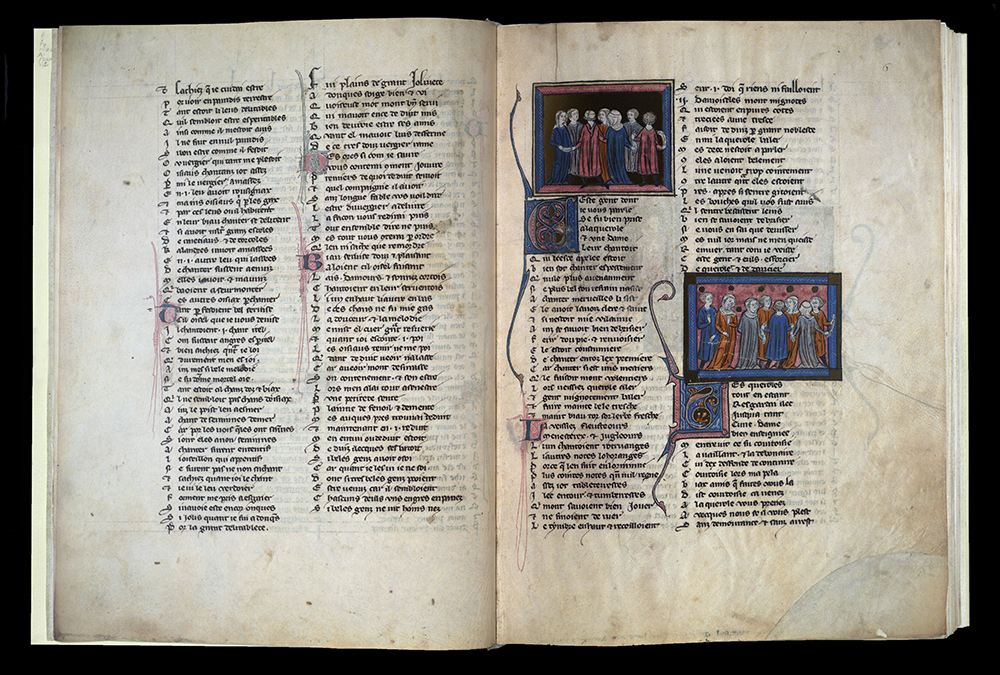

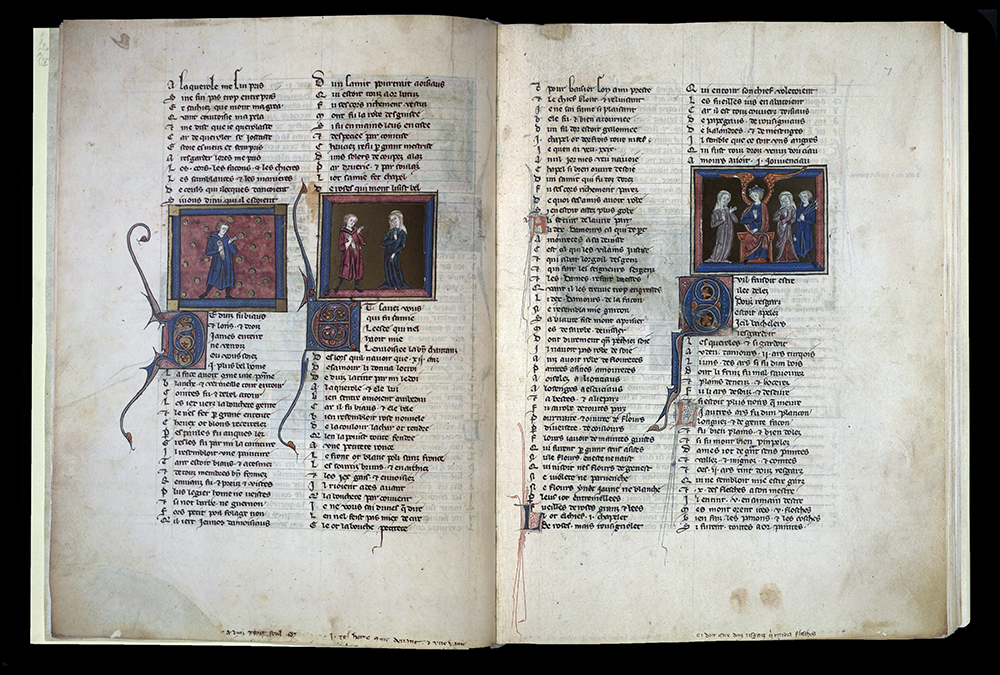

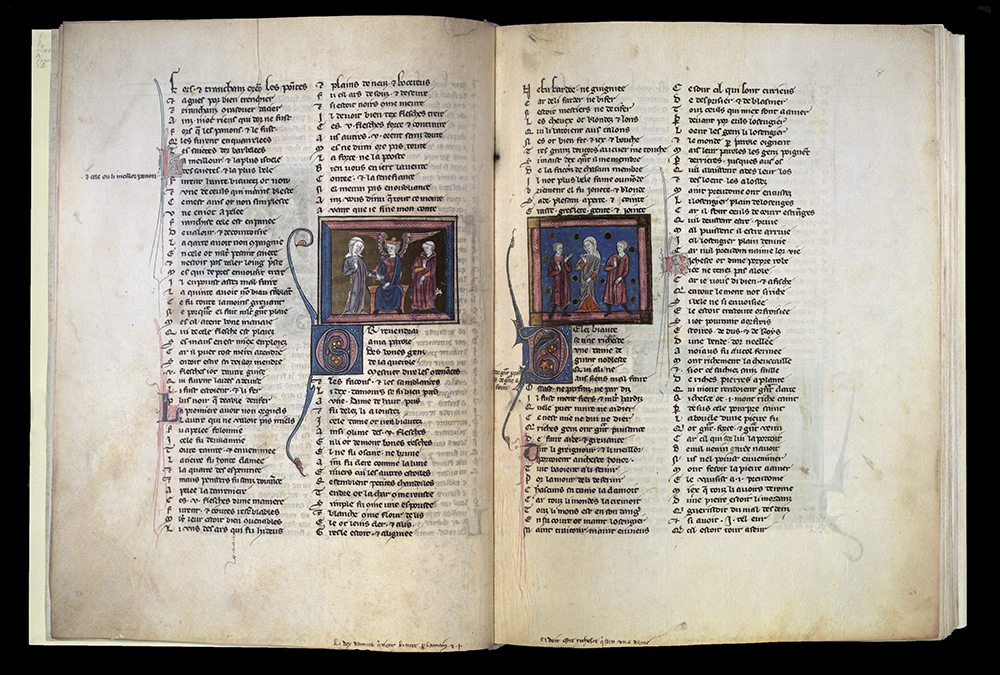

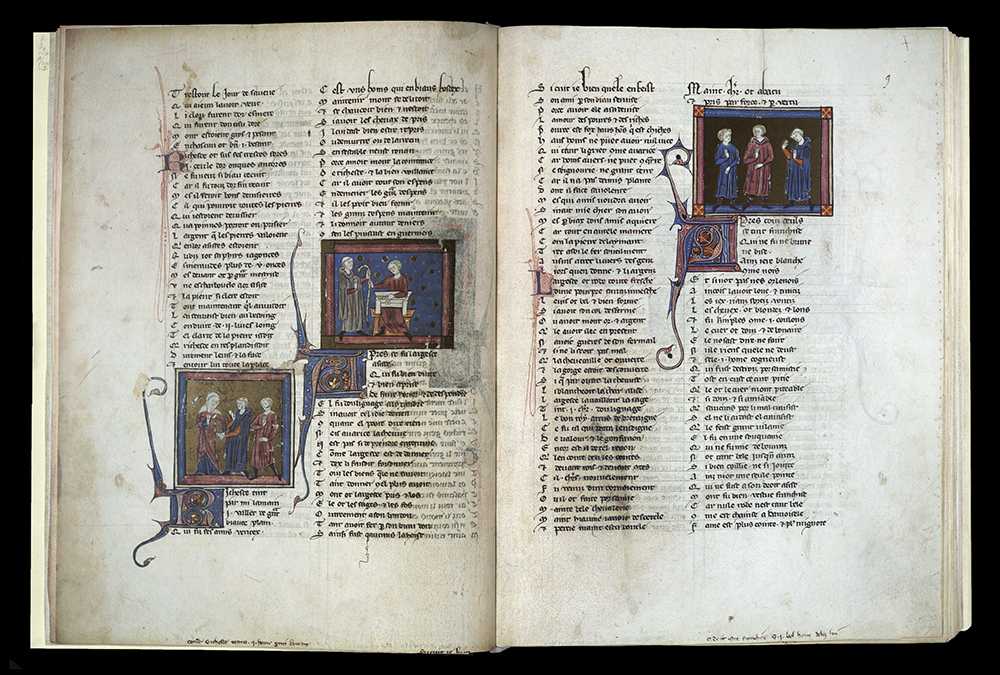

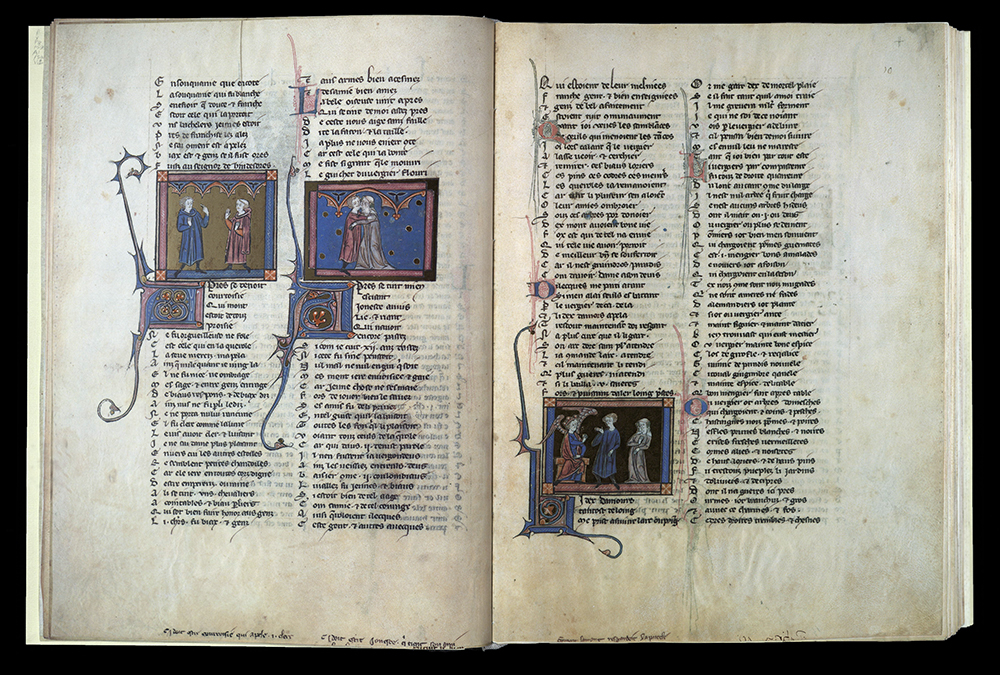

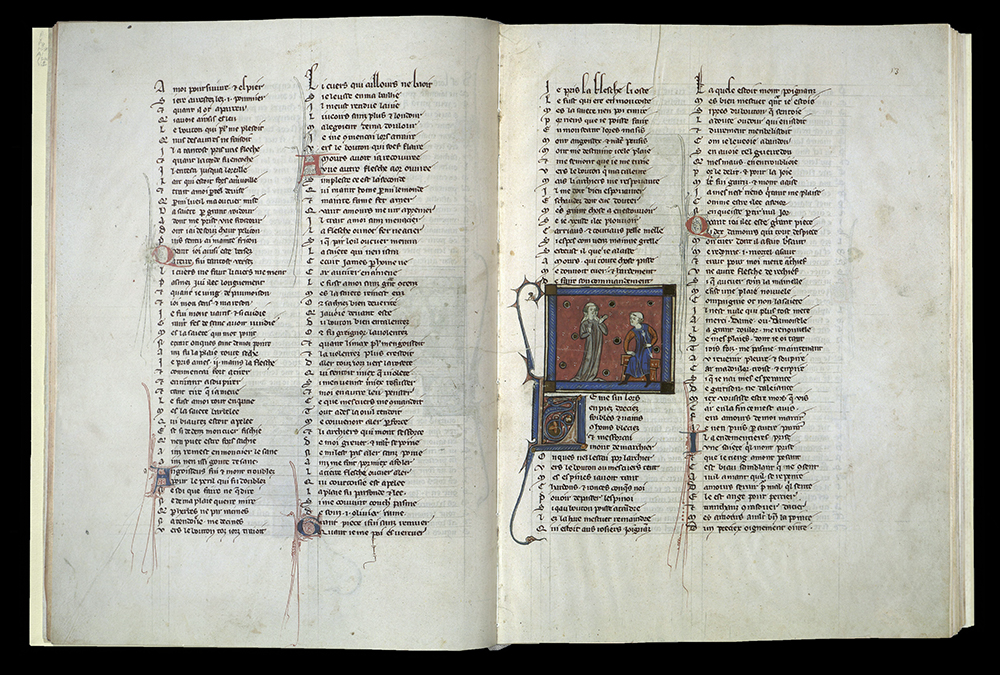

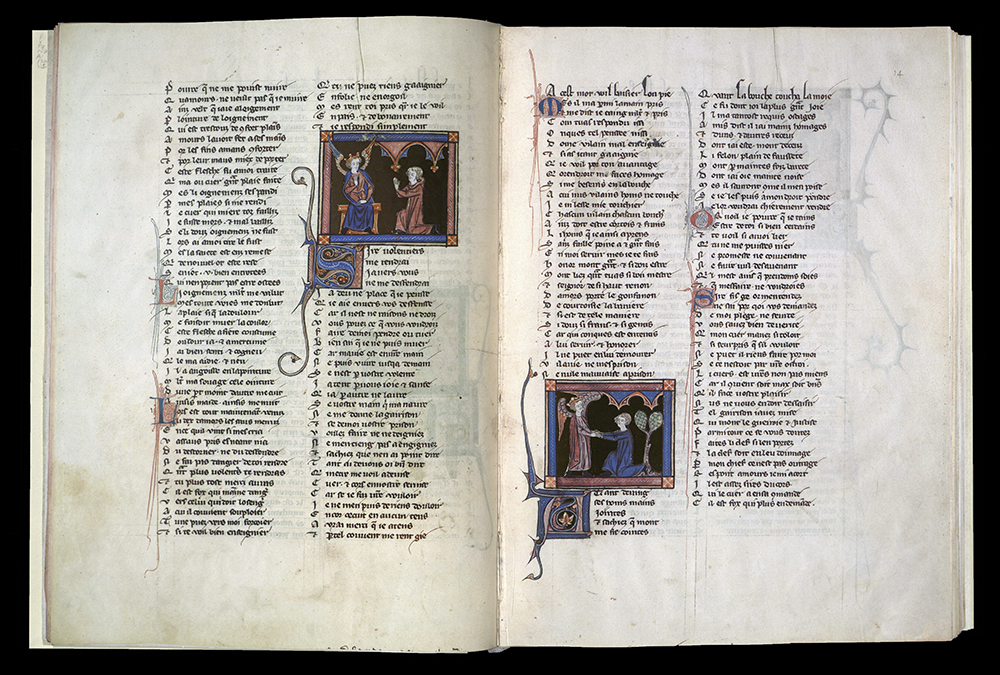

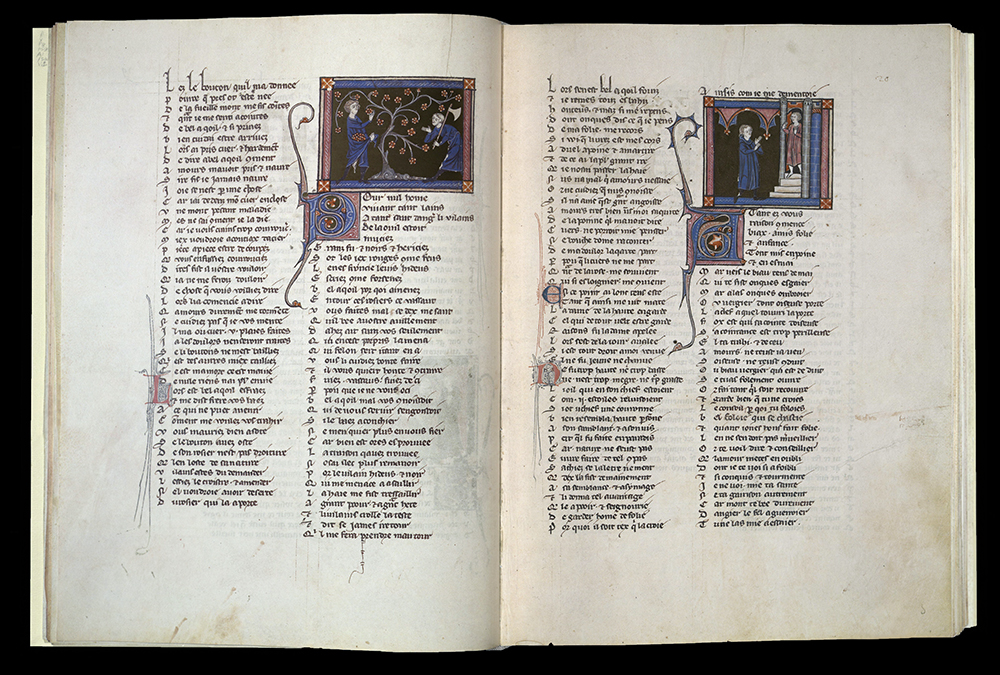

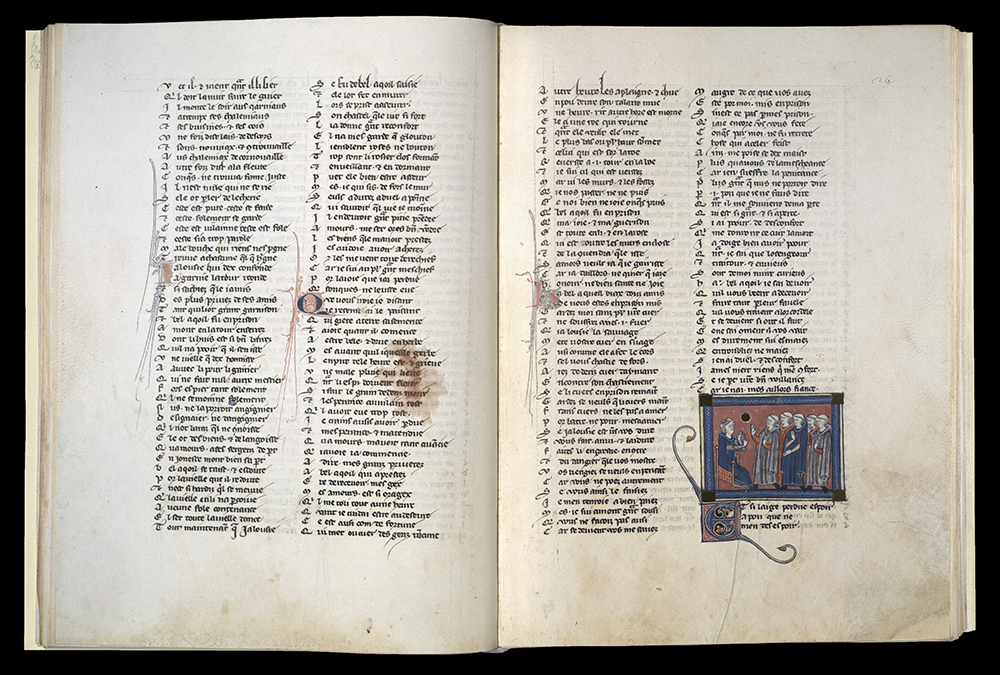

FACSIMILE DER ROSENROMAN DES BERHAUD D'ACHY

Guillaume de Lorris & Jean de Meun

Zürich: Belser Verlag, 1987

PQ1527 A1 1300a

Made in Paris around 1275, this is a copy of an allegorical poem composed by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun within an interval of more than forty years. In the dream vision of the first part, the principal character of the dreamer-narrator-lover sets off in a courtly quest for a rose.

Neither medicinal nor scientific, the symbolic use of one plant, the rose, for true love has lasted into the twenty-first century. Western and Eastern cultures from ancient times used gardens as settings for love stories and all the human foibles that might arise out of that most complex of emotions. The Romance of the Rose contains long descriptive lists of trees, spices, and other plants. The tale helped to fix traditional sensibilities about the beauties of Paradise, influencing the writings of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and others.

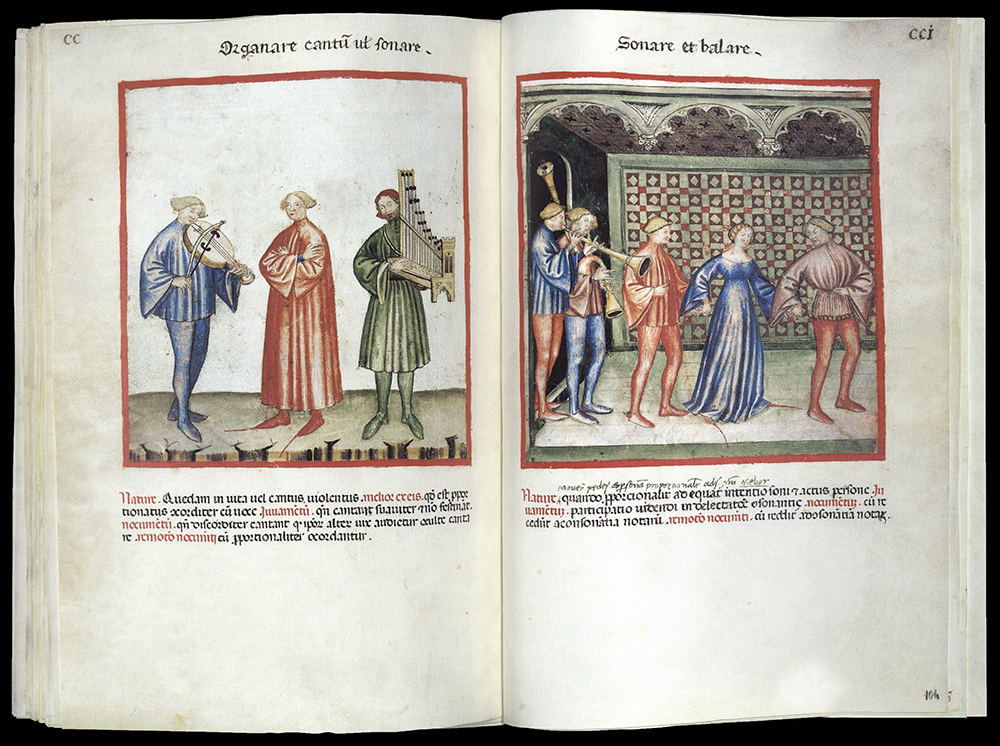

FACSIMILE THEATRUM SANITATIS : BIBLIOTECA CASANATENSE

Ububchasym of Baldach

Barcelona: M. Moleiro Editor, S.A., 1999

RS79 T46 1999

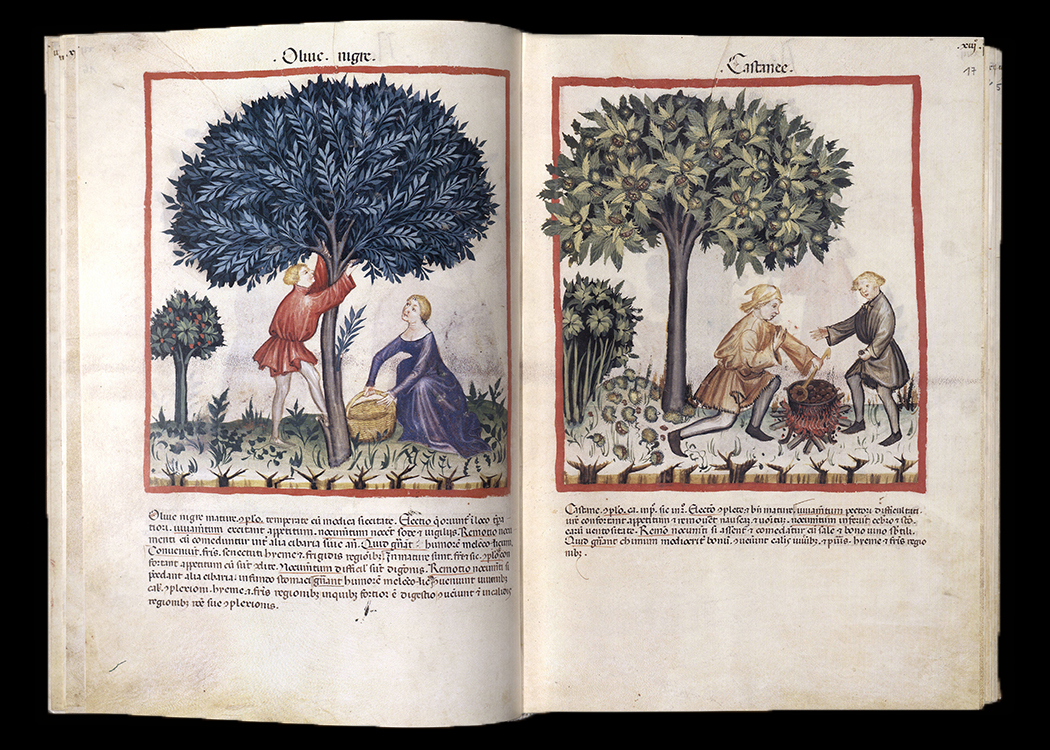

This handbook of health was written between 1052 and 1063 by the Arab Ububchasym of Baldach. Many of the concepts used in his writing were derived from earlier Greek, Roman, and Arabic medical treatises. This manuscript of the work was produced around 1375.

Good health depended upon six essential factors: climate, food and drink, movement and rest, sleep and wakefulness, happiness, pain and sadness. Ninety-nine plants are described with the therapeutic properties of each and the ailments that may be helped by them.

Two hundred and eight red-framed, nearly full-page illuminations illustrate the plants as well as scenes from daily life.

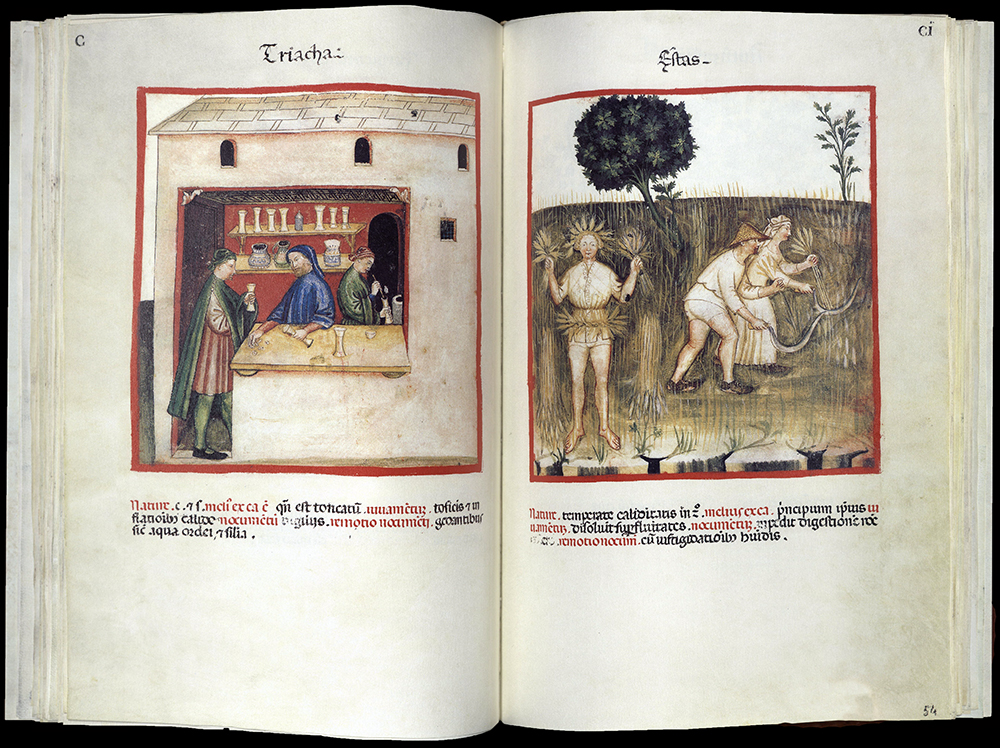

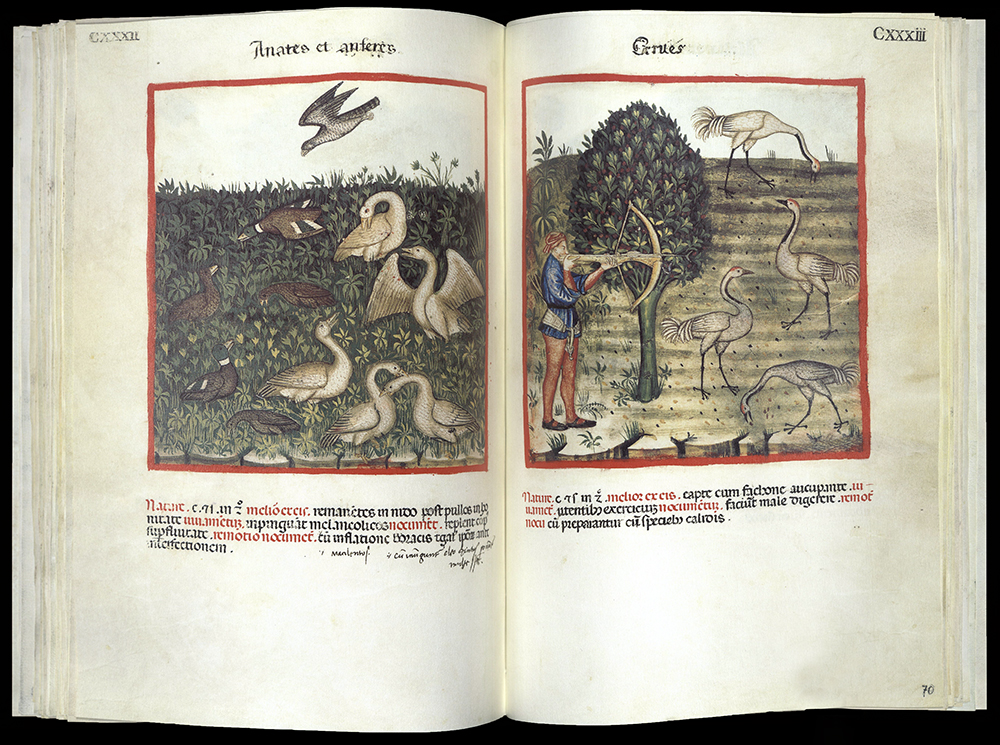

FACSIMILE TACUINUM SANITATIS IN MEDICINA

Ibn Butlan (d. 1066)

Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt, 1986

RS79 T335 1986

FACSIMILE TACUINUM SANITATIS / ENCHIRIDION VIRTUTUM EGETABLILIUM, ANIMALIUM, MINERALIUM ...

Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1984

RS79 T33 1984

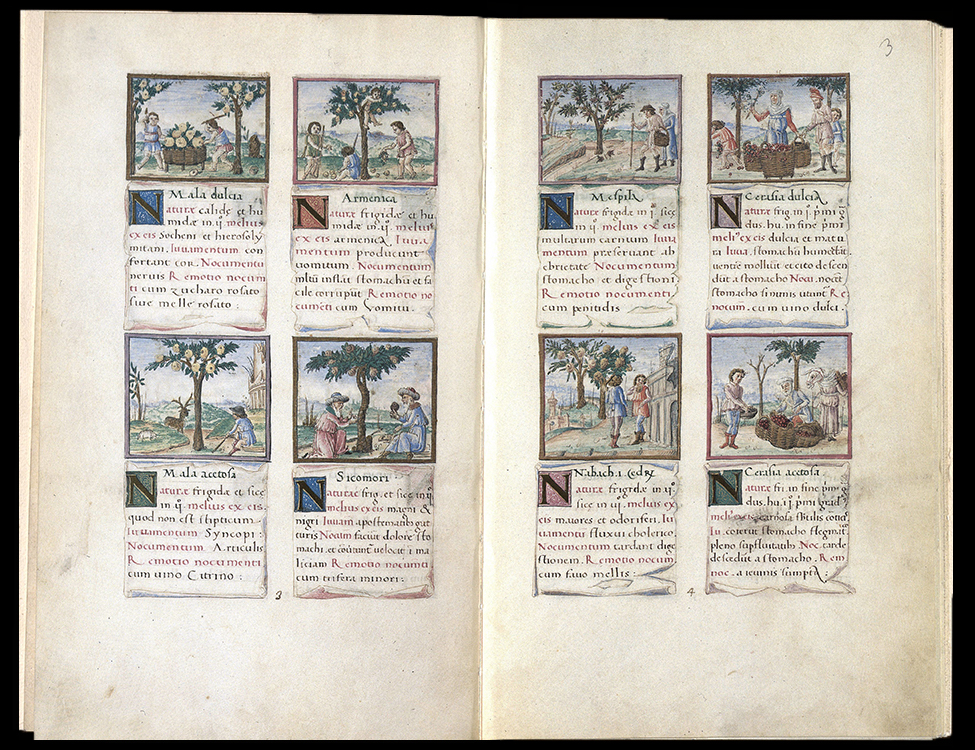

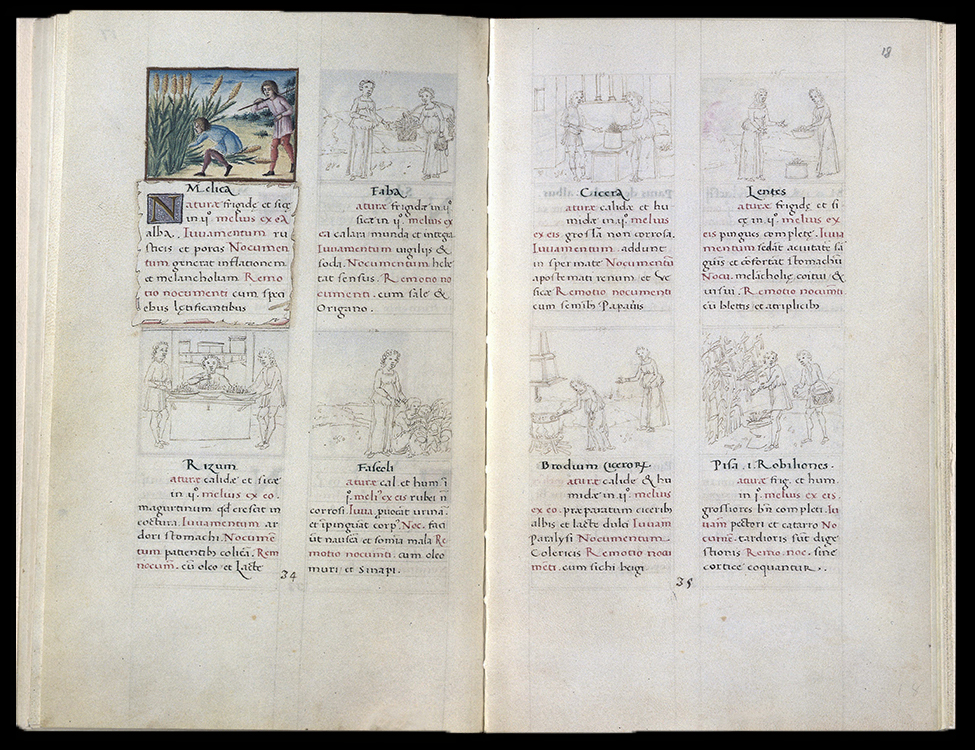

The text for these two copies of Tacuinum Sanitatus, produced nearly one hundred years apart, was based on the Taqwin al-sihhah of Ibn Butlan. Ibn Butlan, originally from Baghdad, visited Cairo about 1090, after which he went to Constantinople before settling at Antioch in Syria, where he became a Nestorian monk.

Derived from the classical herbal tradition, Tacuinum Sanitatus is a reference for the household management of health and healing. The Arab art and science of healing decisively influenced occidental medicine and enjoyed a long-lived and distinguished reputation. Tacuinum combines Arabic and western knowledge on many types of foods and plants with particular reference to their useful and harmful properties.

The Latin translation, which made the codex accessible to the educated of the medieval western world, was widely known. It was one of the most popular treatises on medicine during the late Middle Ages. Many copies survive.

The earlier copy exhibited here was produced in about 1390 for a woman of the upper aristocracy able to read, and afford, a lavishly illuminated book filled with over two hundred full-page miniatures.

The later copy, produced about 1490, is made up of eighty-two leaves, with four miniatures per page, a total of two hundred and ninety-four miniatures. The illumination of the drawings was never finished, giving modern day viewers some insight into the complexities of making an illustrated medieval manuscript.

FACSIMILE LIBROS DE LOS MEDICAMENTOS SIMPLES

Mattheus Platearius

Barcelona: M. Moleiro, 2000

RS81 P614 2000

Herbals were used heavily by physicians and apothecaries during the Middle Ages. This manuscript, produced about 1470, is a French translation of a popular Latin text, written by Mattheus Platearius, probably around 1130-50. Platearius, a teacher at the School of Salerno, the leading medical center of the early Middle Ages, attempted to address several problems that had arisen for physicians confused by names, effectiveness, and the administration of herbs. The title refers to the basic substances used in medicine, the “simples.” It describes pharmacological qualities and side effects of medicinal plants and other substances. For the next four hundred years it was used as a reference book to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of illness.

This copy was probably made for Louise of Savoy, wife of Charles of Angouleme and mother of Francois I. It is illuminated with one hundred and twenty-seven miniatures, eleven of which are intermingled within the text and the rest appended to the end of the book. The illuminations, framed in gold, include scenes from country life.

FACSIMILE LE LIVRE D'HEURES AUX FLEURS

Luzern: Faksimile Verlag, 1991

ND3363 B3 B29 1991

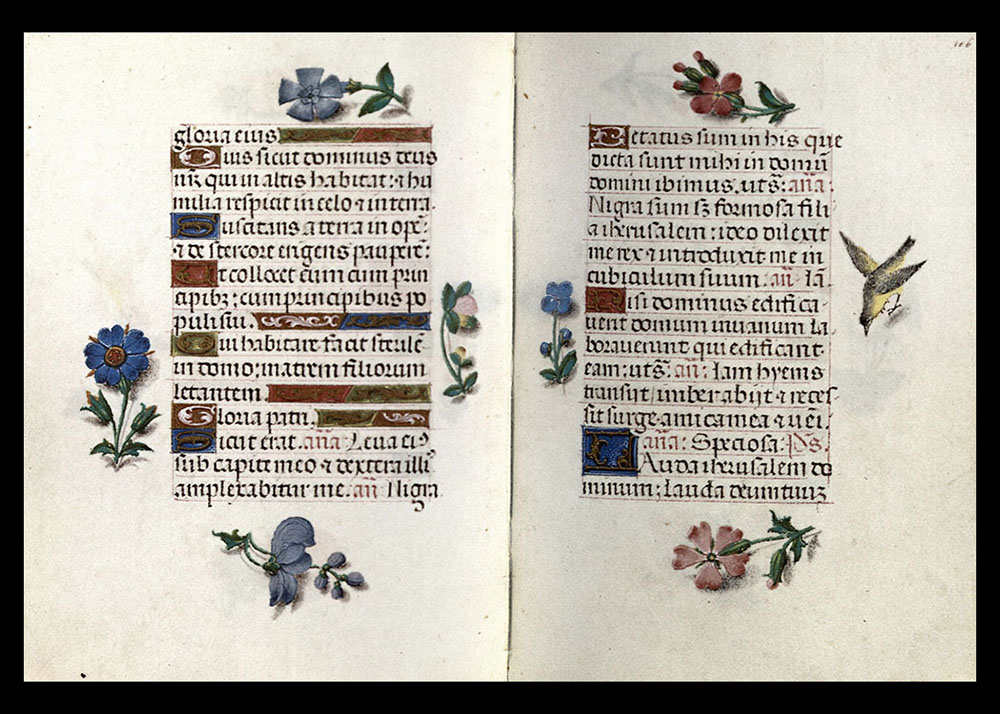

The Flowers Book of Hours, produced by Simon Bening in Flanders around 1516, is one of the most luxurious examples of the popular Book of Hours. A Book of Hours began with a calendar, followed by prayers, sections out of the four Gospels, psalms, and other aspects of religious devotion.

Bening distinguished this Book of Hours with loosely arranged decoration made up of flowers and birds framing the text on each page. Seventy miniatures placed throughout the book depict scenes from everyday life. The son of an illuminator, Simon Bening was one of the last great masters of his discipline.

Only twenty-six years after the Flowers Book of Hours was illuminated by Simon Bening around 1516, and fewer than one hundred years after the advent of printing, Leonhart Fuchs published his landmark botanical work in 1542. This was not an herbal in the medieval sense, but a biological study that relied on scientifically accurate illustrations. The growth of universities resulted in the attachment of herbal gardens to medical schools by the mid-sixteenth century. European travelers and explorers in the sixteenth century returned with new plants, a new appreciation of plants for their decorative as well as medicinal value, and a new stimulus to serious botanical studies. In seventeenth-century Europe the study of plants from all over the world continued to develop. Many botanicals were published, some studies of a general nature, others confined to specific types of plants. Books specifically for gardening were a byproduct of botanical studies. Over the centuries, the methods for reproducing illustrations developed also – enabling finer lines, greater detail, and accurate color. From medieval manuscript illuminations to woodcut and copperplate engravings, aquatints, mezzotints, and lithographs the beauty of nature made for beautiful books.

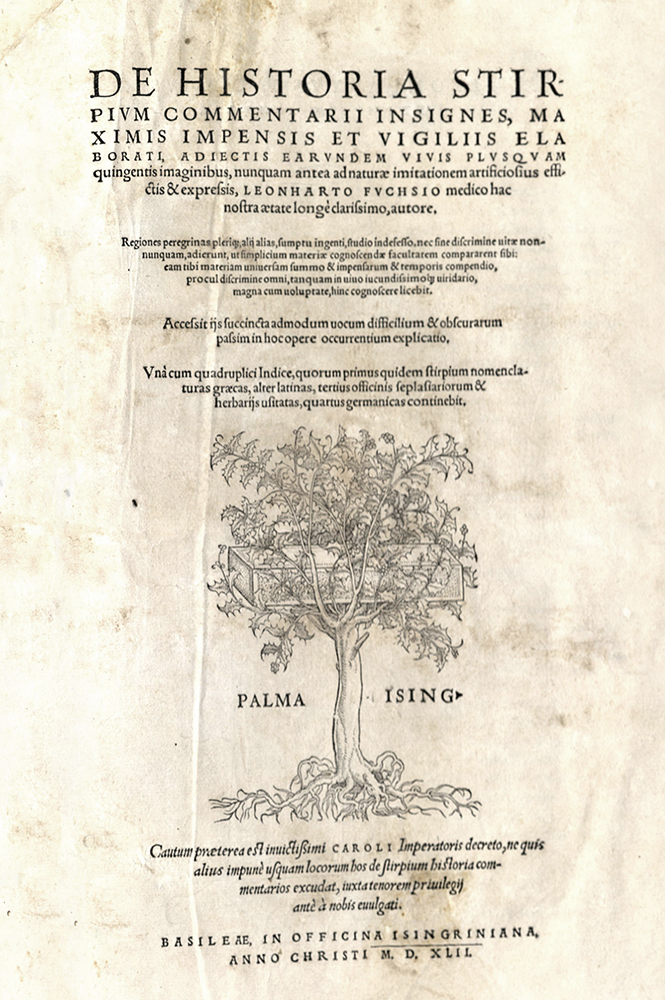

DE HISTORIA STIRPIVM COMMENTARII INSIGNES ...

Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566)

Basileae: In officina Isingriniana, 1542

First edition

QK41 F7 1542

Leonhart Fuchs established a new standard of scientific observation and accurate illustration with his De Historia Stirpium. In his dedicatory letter, Fuchs complained that only a handful of physicians had any real knowledge of plants. For information and plants, physicians relied on illiterate apothecaries, who, in turn, relied on the peasants who gathered the plants. It was as easy to mistakenly poison a patient as it was to cure him.

Five hundred remarkably detailed woodcuts represent the first published illustrations of American plants, including the pumpkin, the marigold, maize, potato, and tobacco – all native to Mexico and introduced into Europe as a consequence of the Columbian Encounter. Arranged according to the Greek alphabet, the plants were also identified in Latin and German. The localities, times of flowering, and uses were all addressed. Indices were compiled. Great care was taken to match descriptions with illustrations.

Leonhart Fuchs was a child genius, matriculating at Erfurt University at the age of twelve. He went on to take a degree in medicine at Ingolstadt. His medical work during an outbreak of plague in 1529 was outstanding and contributed to an already growing reputation. In his De Historia Stirpium he gave full recognition to his artists by praising them in his preface and publishing their portraits. This is probably the first book that contains not only the names, but also the portraits of its illustrators, the best in Basel at the time, and well worthy of this honor. Fuchs would be immortalized with the lovely genus Fuchsia.

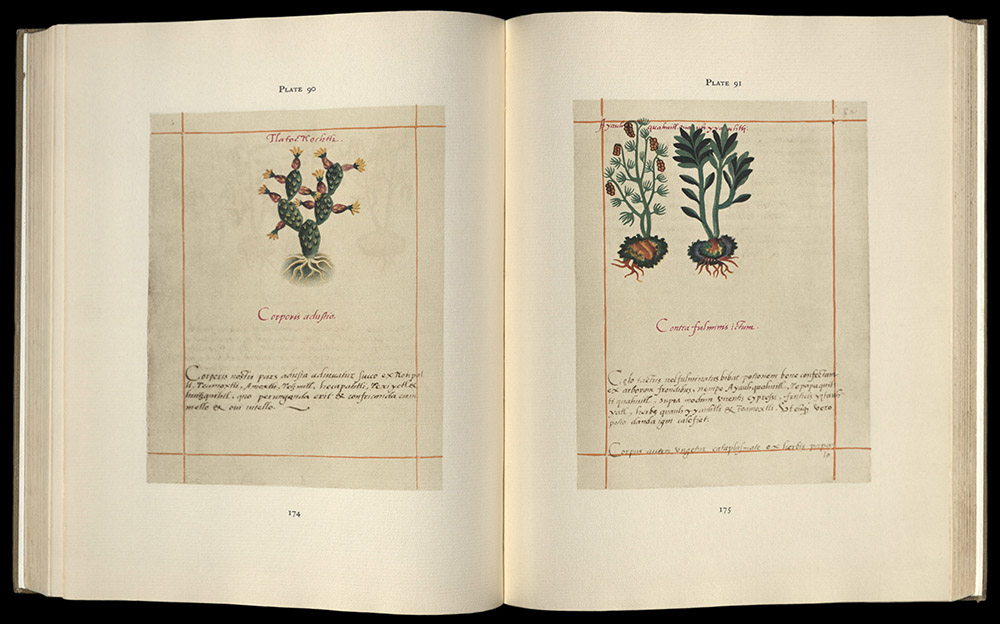

FACSIMILE BADIANUS MANUSCRIPT: CODEX BARBERINI ...

Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1940

First edition

RS169 C7 1552a

This illustrated herbal is the only medical text known to be the work of Aztec Indians, written by an Aztec physician (Martin de la Cruz) and translated into Latin by another Aztec, Juan Badia (Badianus), a scribe in the college of the Holy Cross. The book was presented to Phillip II, King of Spain, in 1552.

The one hundred and eighty-four brilliantly colored illustrations of native plants and trees are the earliest known of American botany, many of which retain their original Aztec names. The wide range of colors, still vivid after over four centuries, is a testimony to the sophisticated and artistic use of natural dyes by the Aztec. The manuscript documents Aztec medicine at the time of the Spanish Conquest, describing pharmacological treatment of diseases. Recipes for combinations of leaves, roots, and barks crushed in wine, mother’s milk, and other ingredients are listed for making plasters and poultices for ailments from boils and fever to joint pain. Cacao, or chocolate, is prescribed for treating fatigue.

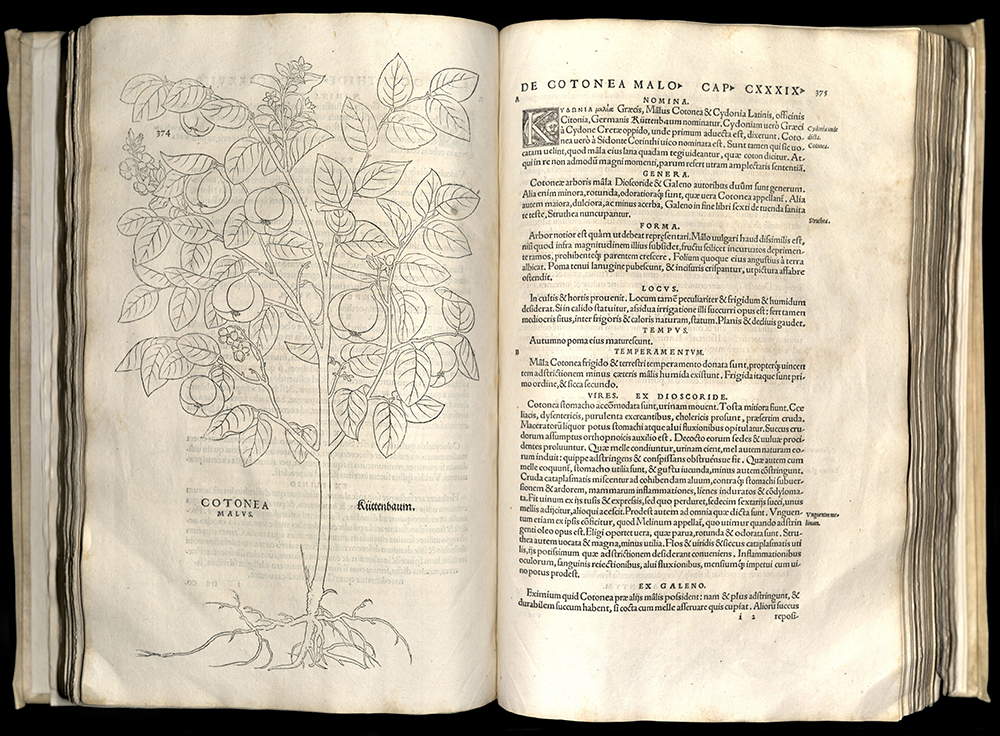

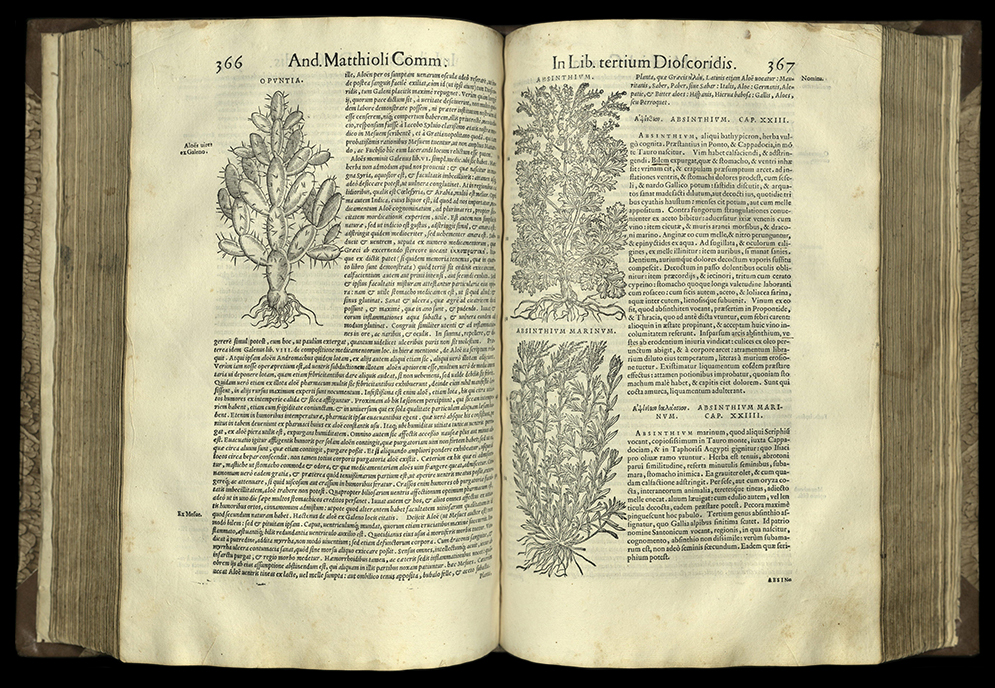

COMMENTARII SECVNDO AVCTI: IN LIBROS SEX PEDACII DIOSCORIDIS ANAZARBEI DE MEDICA MATERIA

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501-1577)

Venetiis: in officina Erasmiana, Vincentij Valgrisij, 1558

QK41 M3 1558

Pietro Mattioli, the son of a physician, became a physician himself after studying in Padua. He served in the court of Ferdinand I and then Maximilian II in Prague. This is the first edition of the Apologia and the second printing of Mattioli’s herbal, which became the standard book on medical botany for European physicians during the second half of the sixteenth century.

Mattioli tried to reconcile the writings of Dioscorides with the writings of Arab botanists and the new botanical discoveries coming from Asia and the Americas. The second printing was substantially revised and enlarged and includes the woodcuts used in the first printing as well as over one hundred new cuts based on the drawings of Giorgio Liberale.

New observations, descriptions of new plants, and its conception and execution as a practical scientific treatise quickly set this work apart from others in botanical literature. The printer of the first Latin edition and fourteen further editions claimed that he sold thirty-two thousand copies within his first early printings.

Printed in italic, Roman, and Greek types, with historiated woodcut initials, and a woodcut printer’s device, it is a sumptuously illustrated book. A contemporary reader glossed the text of this copy with citations to contemporary and classical sources like Hippocrates. A later owner scattered a few notes throughout and filled the final two leaves with pharmaceutical recipes in German.

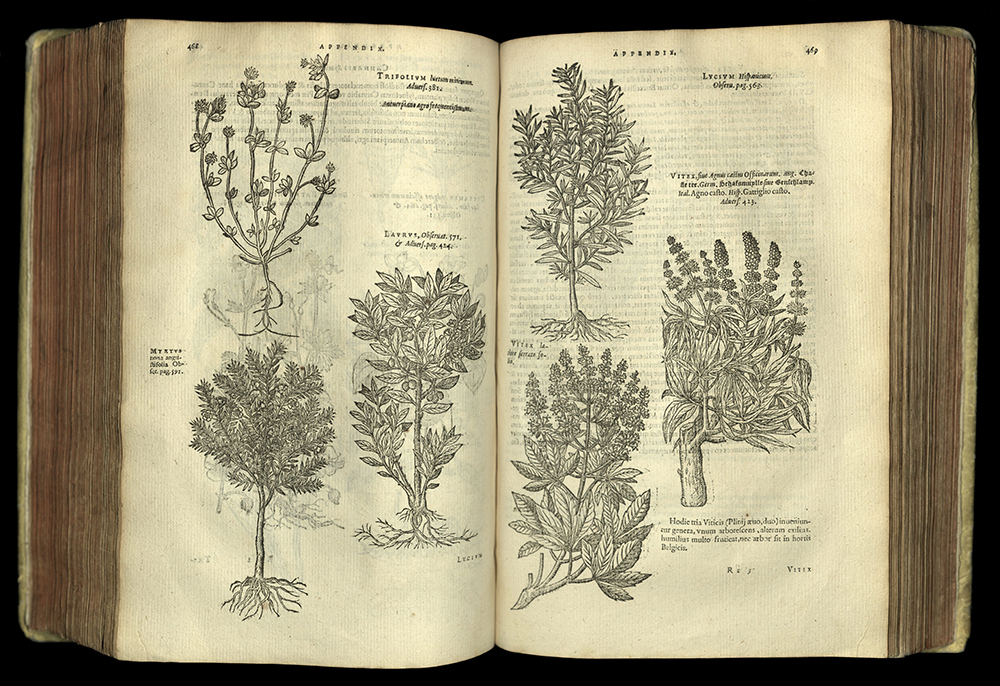

PLANTARUM, SEV STIRPIVM HISTORIA

Matthias de L’Obel (1538-1616)

C. Plantinum, 1576

QK41 L71

Originally printed and published by Thomas Purfoot in London in 1571 as Stirpium Observatones, a larger supplement to his joint work with Pietro Pena. The book was dedicated to Queen Elizabeth. Eight hundred copies were purchased from Purfoot by Christopher Plantin, the leading printer of the time, who provided new title pages and bound them with the author’s Plantarum, sev Stirpivm Historia. The plant Lobelia is named after Matthias L’Obel.

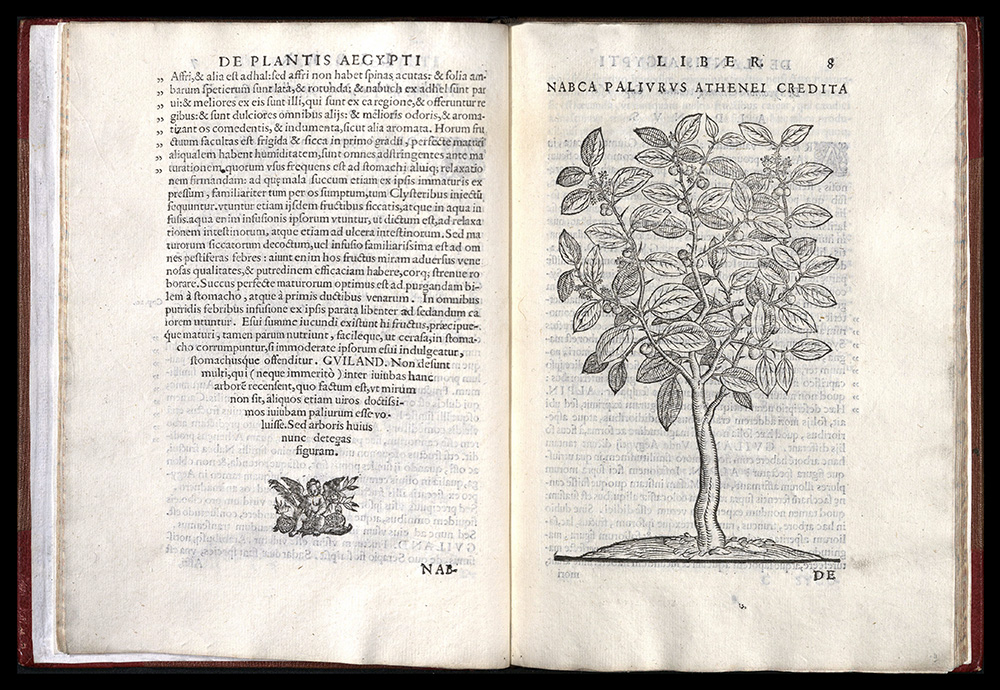

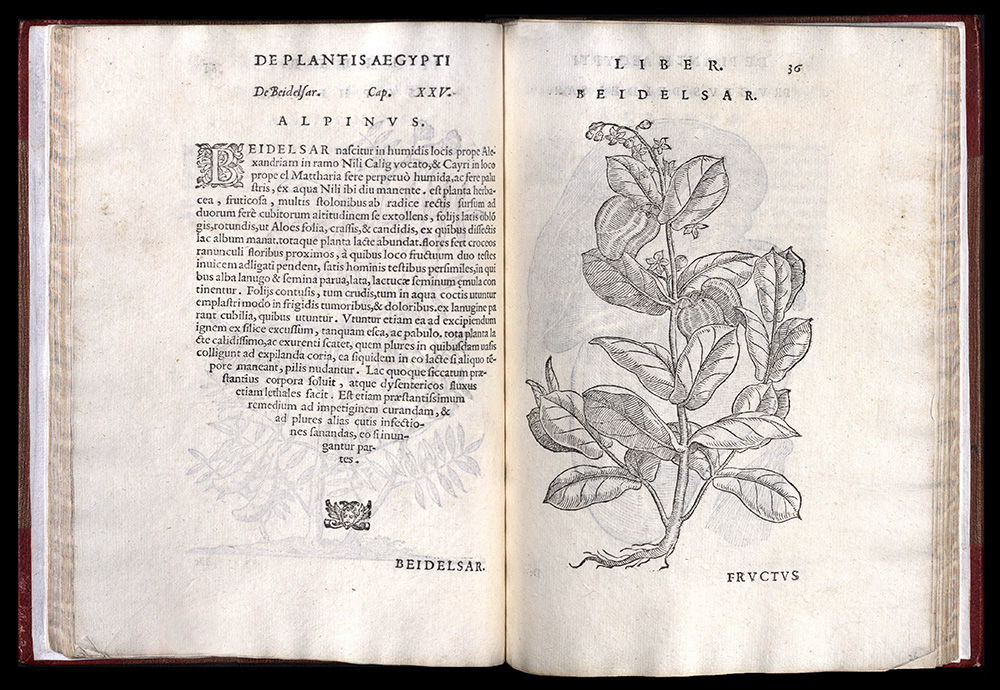

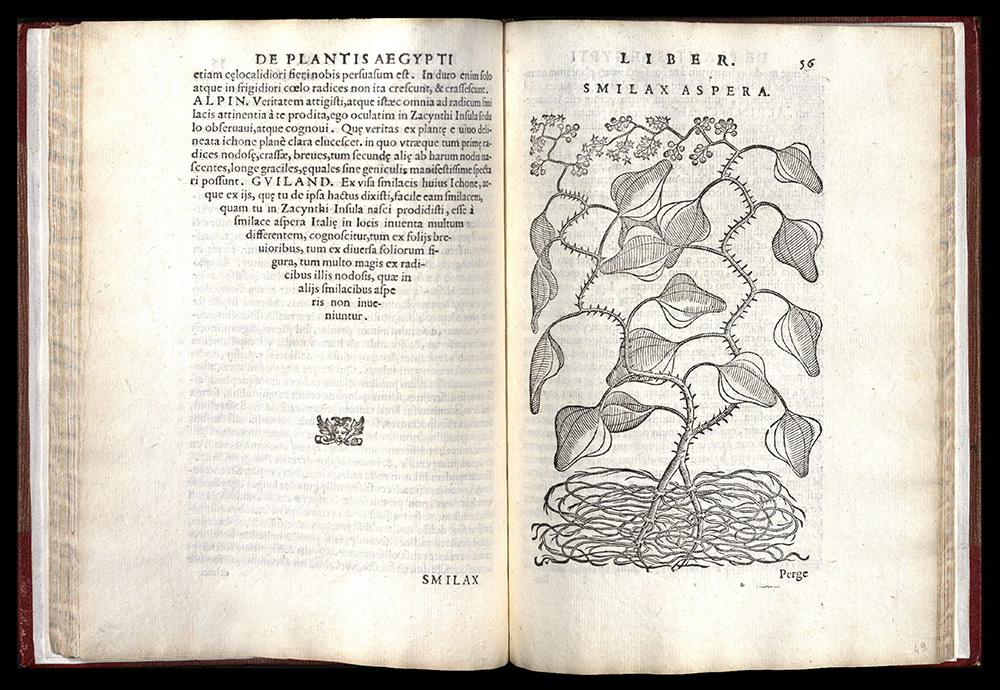

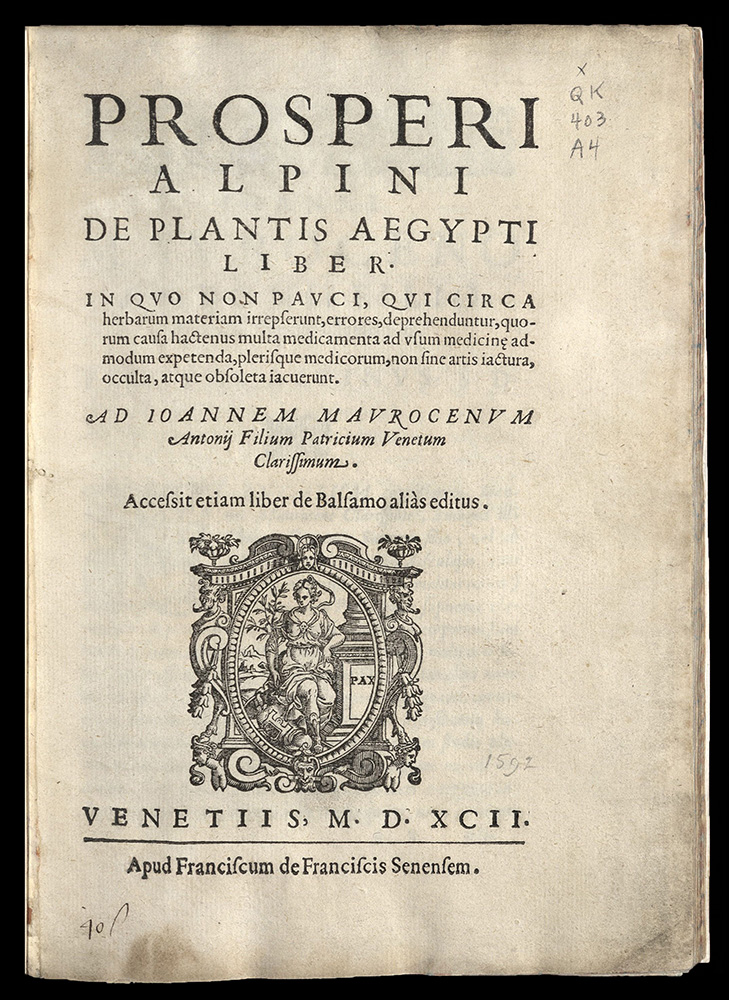

DE PLANTIS AEGYPTI LIBER

Prosper Alpini (1553-1617)

Venetiis: apud Franciscum de Franciscis Senensem, 1592

First edition

QK403 A4

Prosper Alpini, physician and botanist, was educated in Padua. For three years, beginning in 1580, he traveled through the Greek islands and Egypt. In 1593, he was appointed Chair of Botany at Padua. Alpini was the second European writer to mention the coffee plant in a printed book and the first to illustrate and describe it. His works were popular during his lifetime.

One of Alpini’s best-known books is De Plantis Aegypti Liber, a description written in dialogue form of fifty-seven plants found in Egypt and largely unknown in Europe. The woodcuts in this printing are more decorative than realistic.

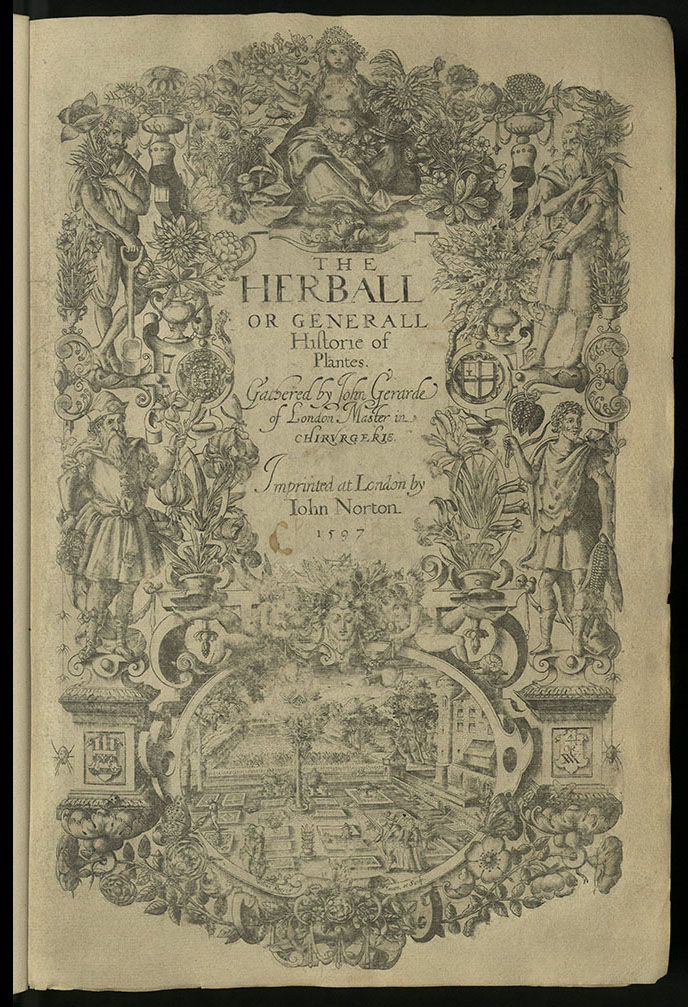

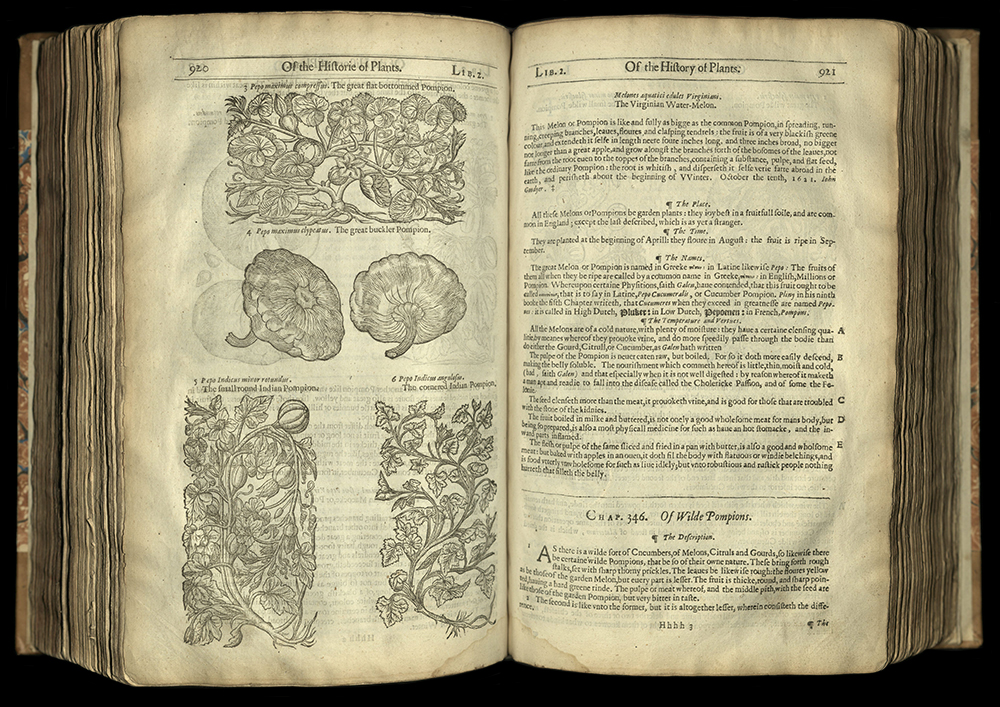

THE HERBALL OR, GENERALL HISTORIE OF PLANTES

John Gerard (1545-1612)

London: John Norton, 1597

QK41 G3

John Norton, Printer to Queen Elizabeth in Latin and Greek, was the first to establish a press at the college of Eton. Norton commissioned a Dr. Priest to translate into English a botanical work of Robert Dodoens. Priest died before his translation was completed. John Gerard was apprenticed as a barber-surgeon and was an ardent horticulturalist and a skilled herbalist. At Norton’s request, Gerard adopted Priest’s work, rearranged it according to L’Obel’s system, and dishonestly published it as his own. The book was a great financial success and went through several editions.

The Herball contains eighteen hundred woodcuts and gives a description of each plant and where it might be found, the origin of its name, its medicinal properties, and disposes of many superstitions connected with plants. Many plants from the American continents are described, including the potato, pictured for the first time in this book.

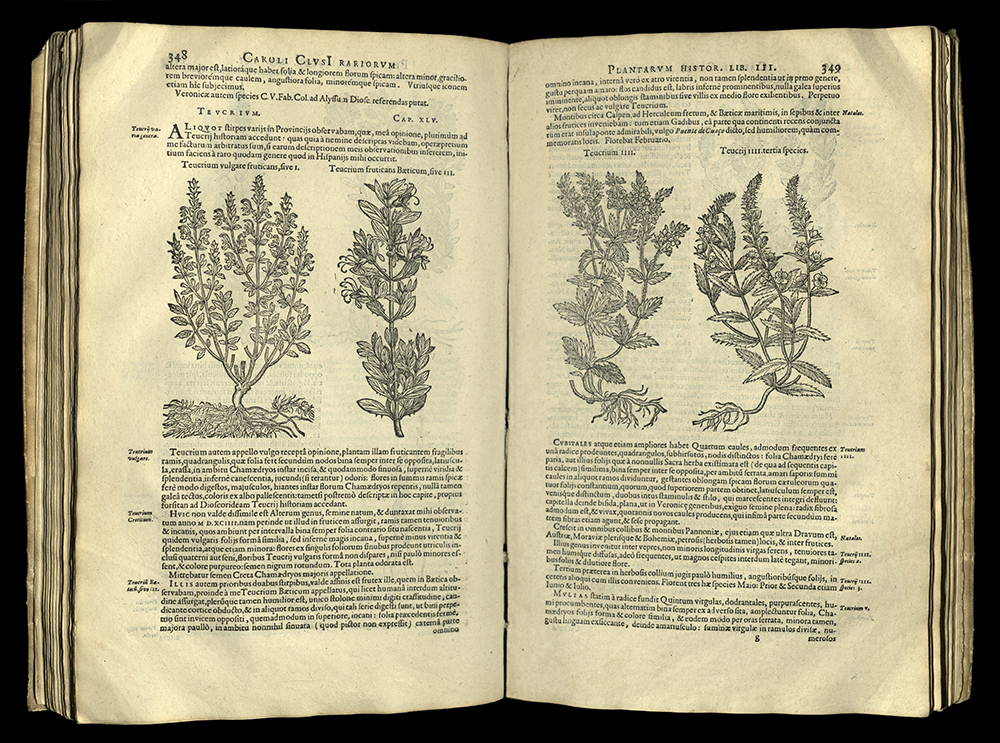

CAROLI CLVSI ATREBATIS ... RARIORVM PLANTARVM HISTORIA

Carolus Clusius (1526-1609)

Antwerp: ex officina Plantiniana apud Ionnam Moretum, 1601

First edition

QK41 L42

The work of Carolus Clusius (Charles de L’Ecluse) is considered the starting point for our modern knowledge of many genera. His work was highly practical. Although he added little to the field of classification, his descriptions remain valuable even today because of his genius for detecting the essential specific features of plants. This collection of his earlier works includes descriptions of plants he found in his travels in Spain and Vienna, where he studied specimens which had come from Constantinople.

One of the most notable plants included in this study is the Jacobean lily from Central America. A specimen was sent to Clusius by a Spanish physician. Clusius noted that it flowered for him in June 1594 and was “called in Mexico azcol xochitl.”

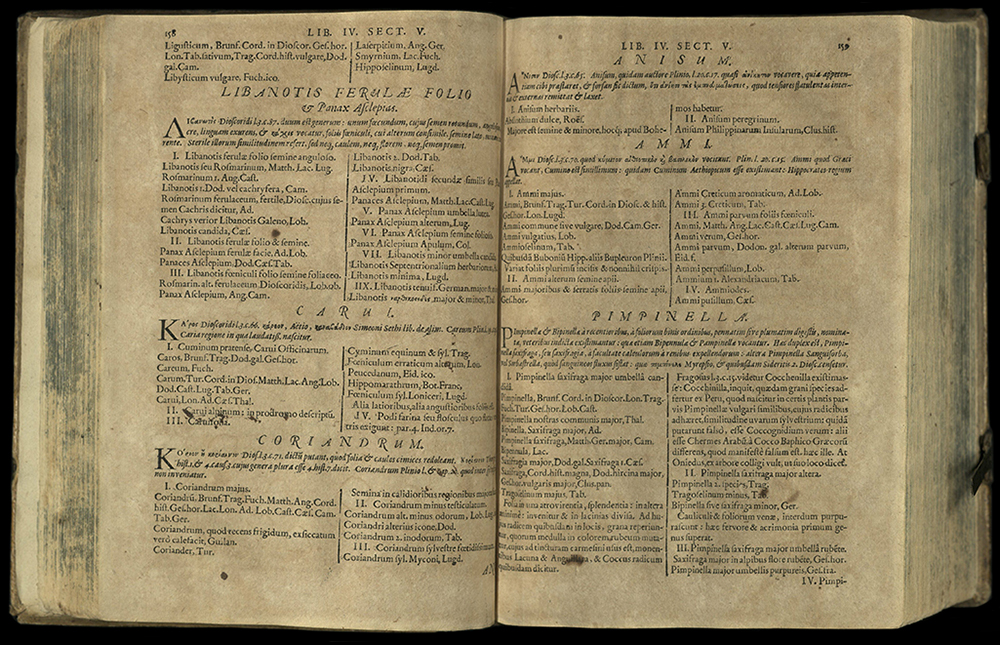

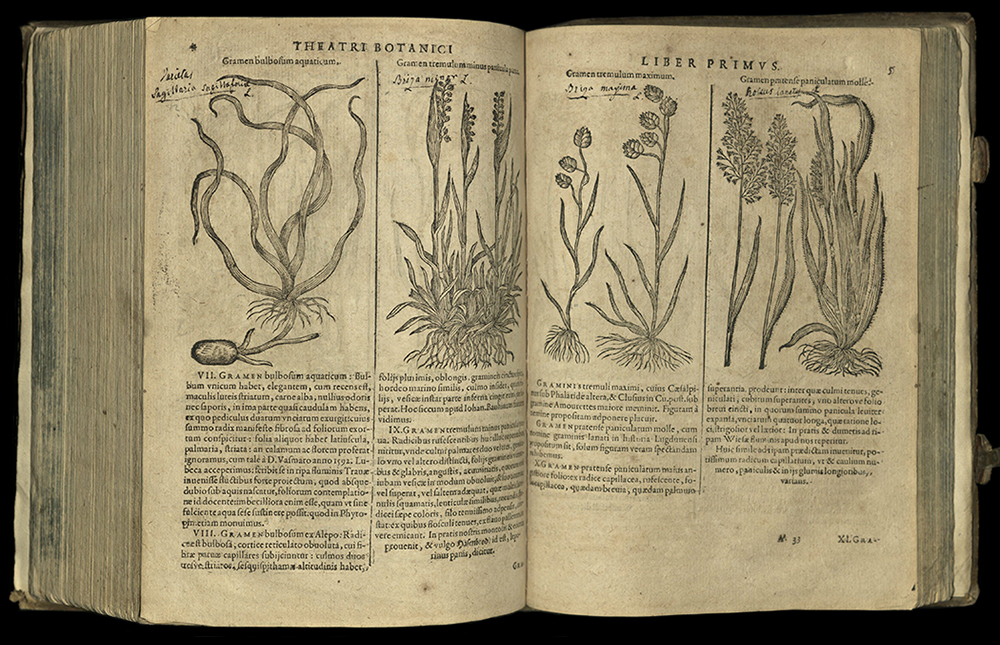

PINAX THEATRI BOTANICI

Caspar Bauhin (1560-1624)

Basileae Helvet., sumptibus et typis Ludovici Regis, 1623

First edition

QK41 B34

Caspar Bauhin, a Protestant refugee from France who settled in Switzerland, wrote this comprehensive concordance of all known plant names at a time when no standardized system of nomenclature had been established. His list was used for over one hundred years until it was replaced by the work of Linnaeus in 1753.

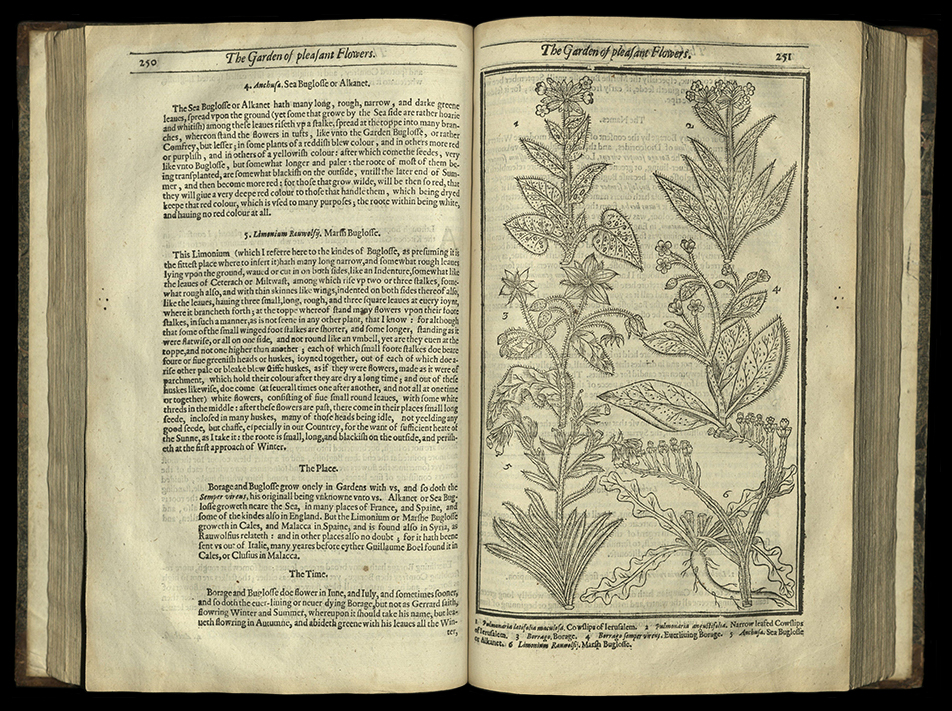

PARADISI IN SOLE PARADISUS TERRETRIS, OR AGARDEN OF ALL SORTS OF PLEASANT, FLOWERS ...

John Parkinson (1567-1650)

London: Printed by Hvmfrey Lownes and Robert Yovng at the signe of the Starre on Bread-street, 1629

First edition

SB97 P24 1629

John Parkinson was Apothecary to James I and, after the publication of Paradisi in 1629, was made Herbalist to Charles I.

Paradisi contains one hundred and nine rather undistinguished woodcuts of more than seven hundred plants. Still, it was and is highly regarded for its delightful text.

The title of this first and best-known work by John Parkinson is a pun on his name. The Latin is translated into English, “Park in sun’s earthly paradise.” Parkinson dedicated this book to Queen Henrietta Maria and termed it a “feminine work of flowers.”

The emphasis of Paradisi reflects the growing interest in ornamental gardens as contrasted to the use of plants solely for medicinal and culinary purposes.

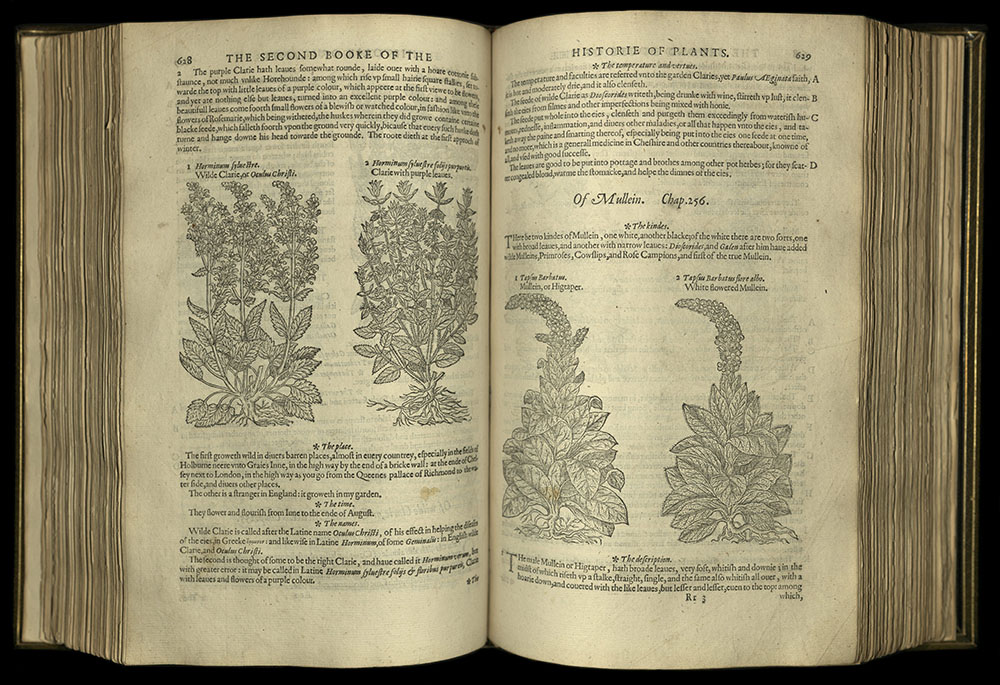

THE HERBAL, OR GENERALL HISTORIE OF PLANTES

John Gerard (1545-1612)

London: Printed by A. Islip, J. Norton & R. Whitakers, 1633

Second edition, very much enlarged and amended by Thomas Johnson

QK41 G3 1633

This work contains descriptions of more than twenty-eight hundred plants, most of which are depicted in woodcut illustrations first used by the publishing house of Christopher Plantin in Antwerp. The second edition reflected the great progress made in botany in the thirty-six years since the book was originally published. More than eight hundred species and seven hundred figures were added, along with numerous corrections. Thomas Johnson, editor of this edition, also corrected many errors, and improved upon the accuracy of the illustrations. Johnson himself was a well-known apothecary.

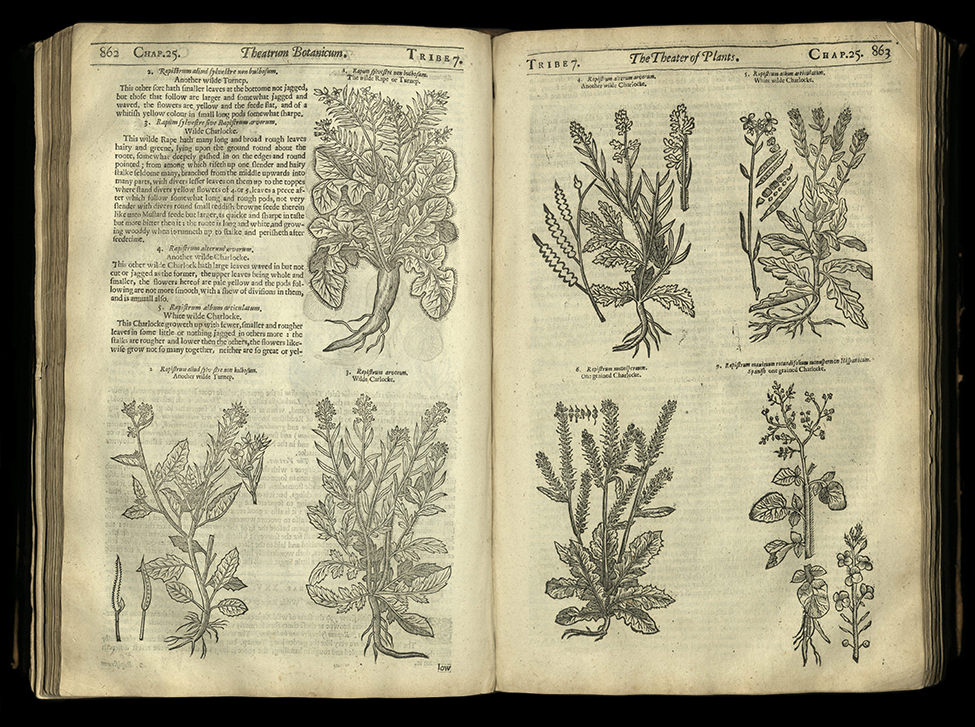

THEATRUM BOTANICVM

John Parkinson (1567-1650)

London: Printed by T. Cotes, 1640

First edition

QK41 P2

John Parkinson was well acquainted with Thomas Johnson, the editor and reviser of Gerard’s Herball. Theatrum is Parkinson’s second and major work, dedicated to Charles I. Parkinson borrowed from the work of many others, quoting them liberally, and adding his own knowledge gained from his study of medicinal plants.

Medieval plant lore still played a part in Parkinson’s writings. He included in this work, for instance, the legendary Vegetable Lamb – a plant topped with a woolly lamb.

Parkinson introduced seven new plants into England and was responsible for the first mention of thirty-three different native plants which had gone unnoticed by previous herbologists. He created an Edenic world in his Theatrum wherein he defined roles of masculinity and femininity by suggesting that plants have similar characteristics in the healing process. Although Parkinson classifies the plant life in his book by “Tribes,” his plant descriptions are quite scientific.

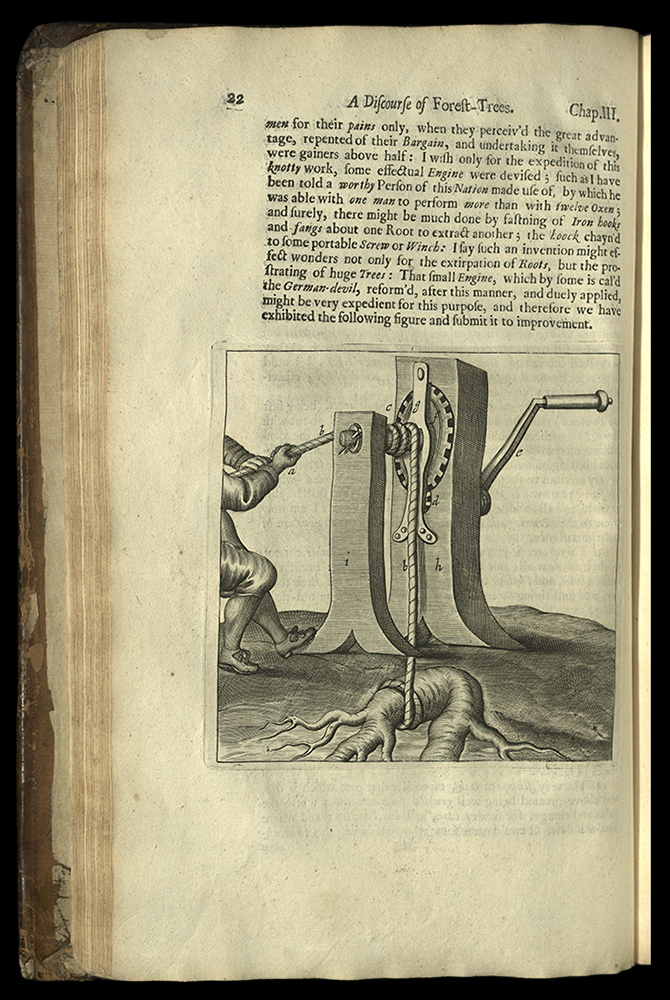

SYLVA, OR A DISCOURSE OF FOREST-TREES

John Evelyn (1620-1706)

London: Printed for J. Martyn, & J. Allestry, Printers to the Royal Society, 1670

Second edition much enlarged and improved

SD391 E93 1670

John Evelyn, the son of an English country gentleman, spent the years between 1643 and 1647 in France and Italy, and traveled abroad again for most of 1649-52. In 1652 he settled near Greenwich and began cultivating his garden. He developed a lifelong interest in the rarities of nature. He was one of the original Fellows of the Royal Society, and was its secretary in 1672-3. In later life, he became an expert in several fields, and published a number of minor works.

Through the end of the seventeenth century, Sylva (first published in 1664) became the chief source of information on the cultivation of trees and the uses for the various kinds of timber. Evelyn, writing mainly for gentile landowners, expressed himself in decidedly undemocratic tones. His pompous writing style made it difficult even for specialized scientists to read.

Much of the material for Sylva was gathered from fellow Royal Society members, including John Winthrop, but many of the “facts” used in Evelyn’s work had been handed down by word of mouth. One biographer of Henry David Thoreau suggests that much of Thoreau’s conservation ethic derived from Evelyn’s writings on the subject.

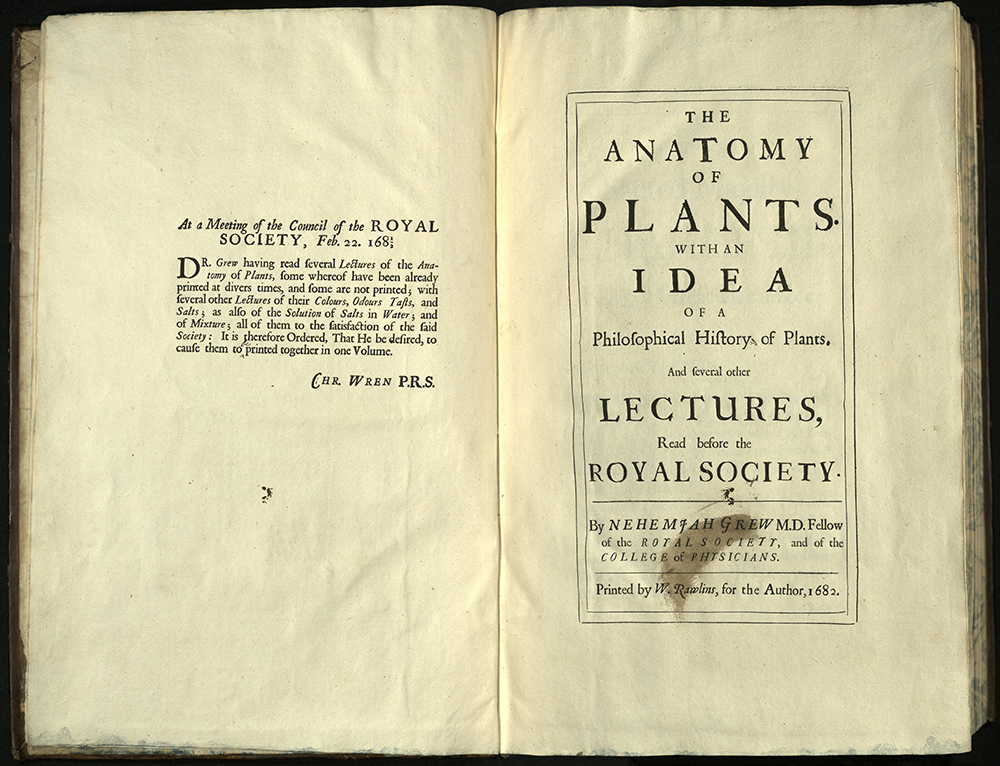

THE ANATOMY OF PLANTS WITH AN IDEA OF A PHILOSOPHICAL HISTORY OF PLANTS ...

Nehemiah Grew (1614-1712)

London: Printed by W. Rawlins for the Author, 1682

First edition

QK41 G82

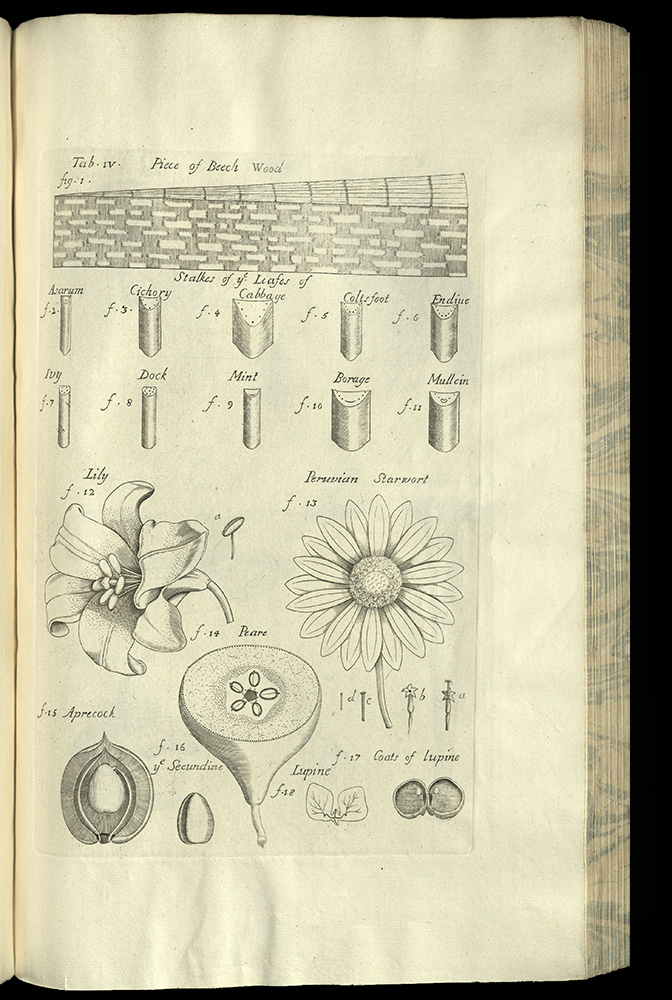

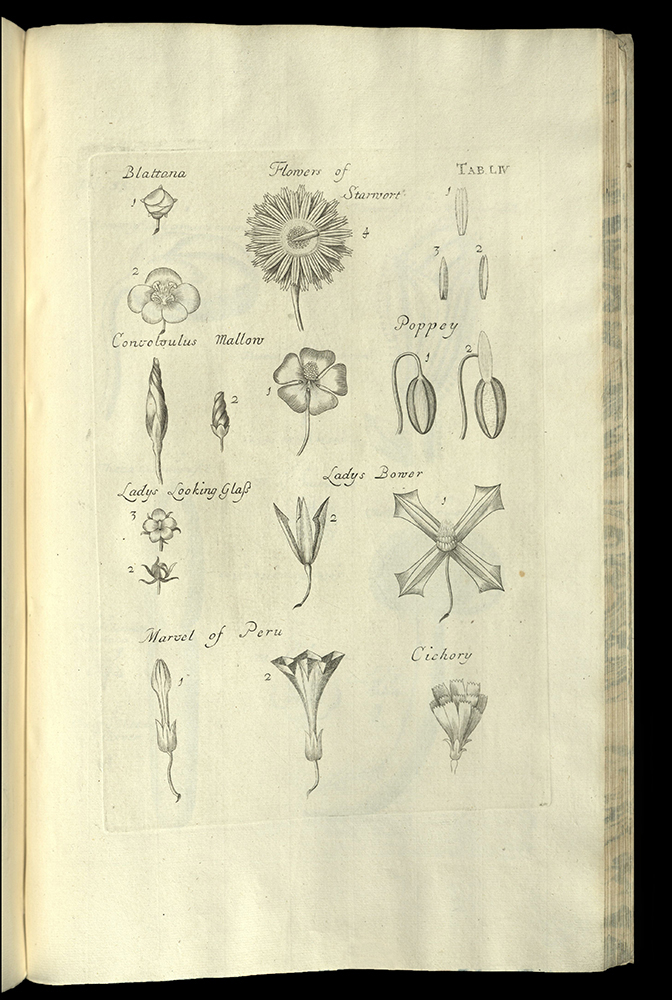

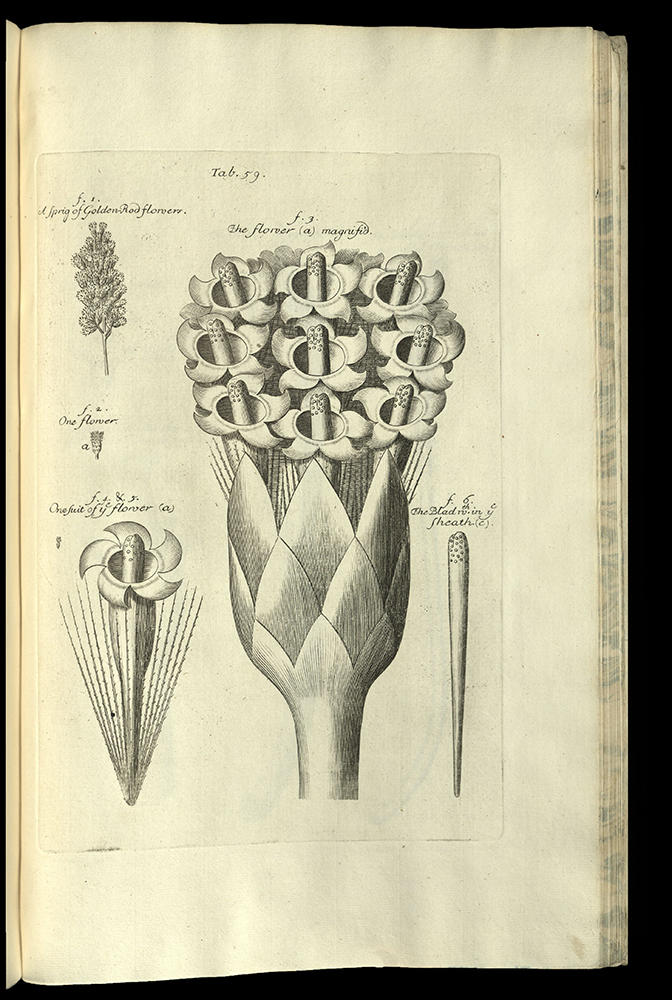

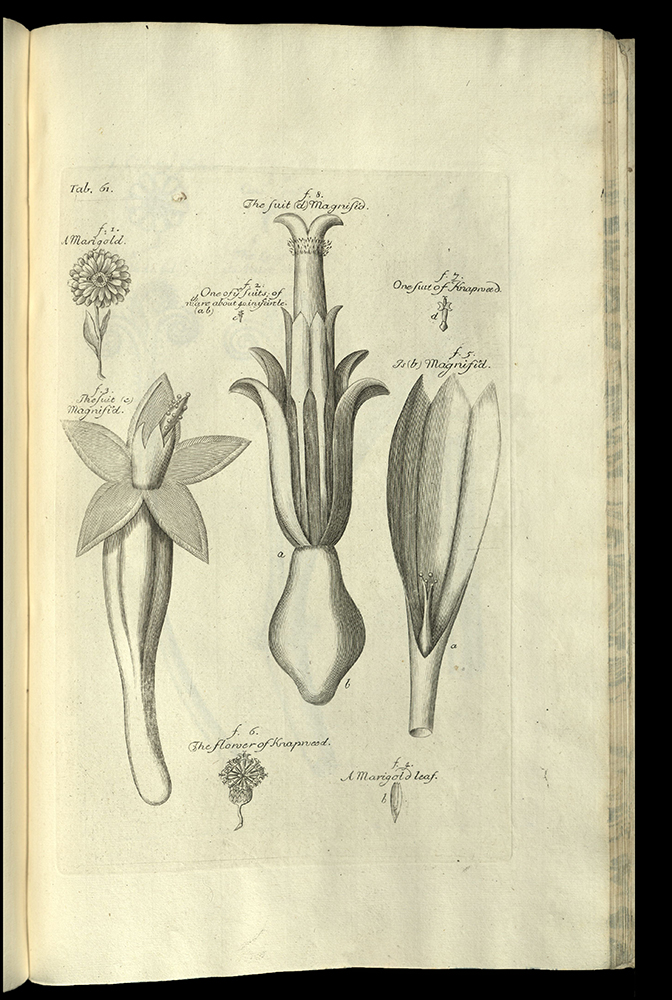

Nehemiah Grew’s work turned the anatomy and physiology of plants into a new science. This was the first book in which Robert Hooke’s newly invented microscope was used to examine plants. It is also probable that this is the first time that the reproduction of plants was described as sexual.

Anatomy contains eighty-one full page and four double-page engravings of plants. Linnaeus dedicated a genus of trees to Grew in appreciation of his work. Few important advances on the ideas of Grew would be made for nearly one hundred years.

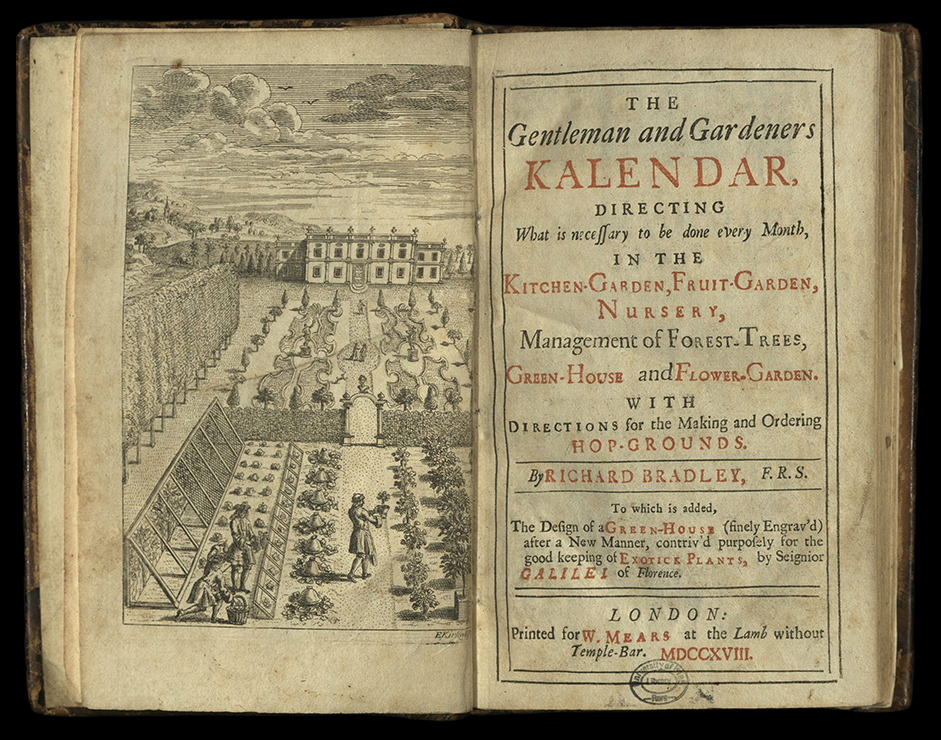

THE GENTLEMAN AND GARDENERS KALENDAR DIRECTING WHAT IS NECESSARY TO BE DONE EVERY MONTH ...

Richard Bradley (1688-1732)

London: Printed for W. Mears, 1718

SB453 B73

Bradley was the first professor of botany at Cambridge. He was a popular botanical and horticultural writer, but not particularly well thought of by his academic colleagues, some of whom suggested that Bradley obtained the Chair of Botany at Cambridge by fraud and lost it by idleness and incompetence.

INSTITUTIONES REI HERBARIAE

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708)

Parisiis: e Typographia Regio, 1719

Editio 3, appendicubus aucta ab Antonio de Juseeieu

QK41 T6 1719 vols. 1-3

First published in 1700, Tournefort’s definition of botany strayed little from that of ancient botanists. In the preface to his history of botany, Tournefort divides botany into two parts: the knowledge of plants, and the knowledge of the uses of them.

One dried specimen still rests on the corresponding page of this copy, left by an unknown reader.

THE GARDENER'S DICTIONARY ...

Philip Miller (1691-1771)

London: Printed for the author, 1733

Second edition

SB45 M6 1733

Philip Miller, gardener to the Apothecaries’ Society and a member of the Society of Gardeners, which had been founded around 1724 to protect the interests of nurserymen, was considered one of the great English gardeners of his time. Miller is thought to be the first person to recognize and report on pollination by insects.

A GENERAL NATURAL HISTORY …

John Hill (1714?-1775)

London: T. Osborne, 1748-52

First edition

QH15 H55 1748

Englishman John Hill is credited with introducing the Linnaean classification system to England. Sixteen uncolored plates of specimens illustrate his book.

Rare Books copy is signed by past owner Jules Remy, a noted French naturalist and explorer who wrote a history of the Mormons, published in 1860.

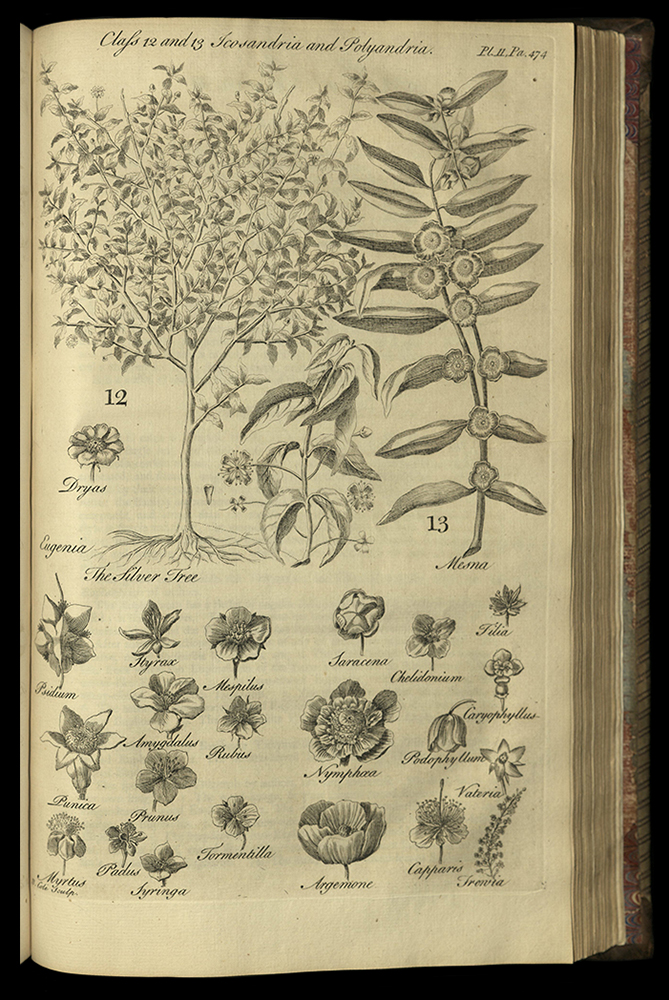

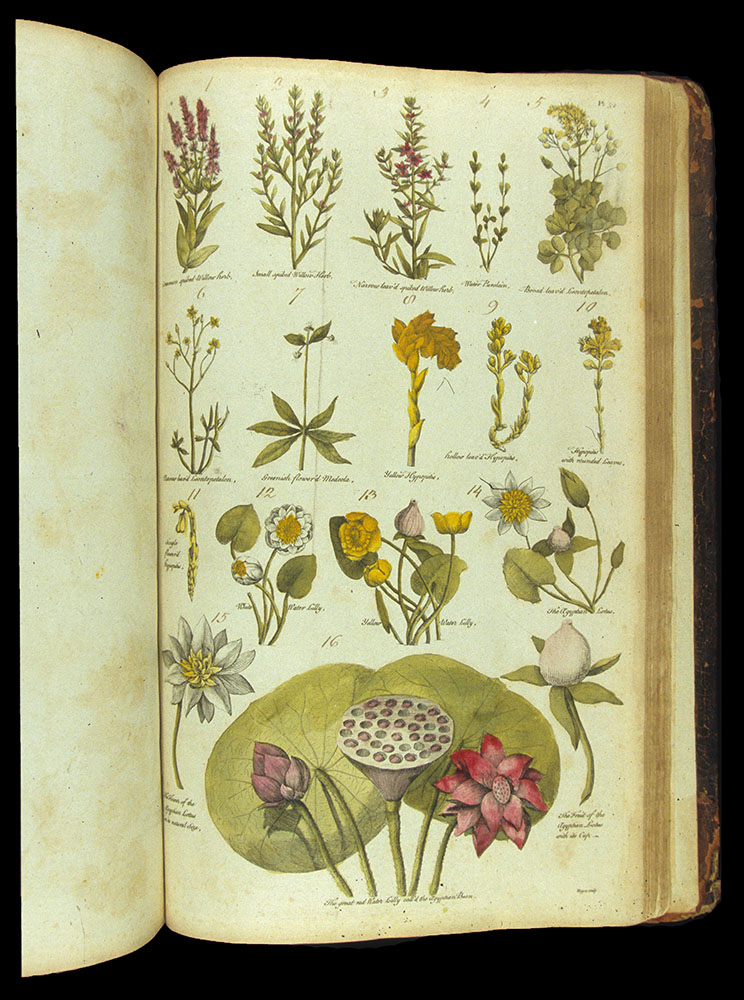

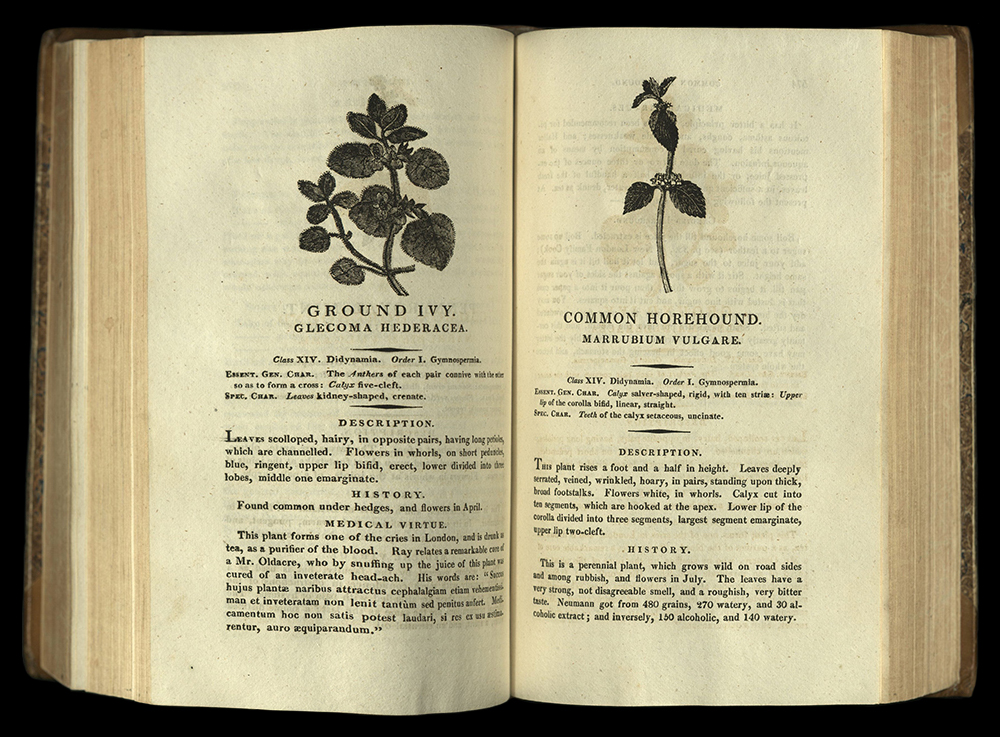

THE BRITISH HERBAL

John Hill (1714?-1775)

London: Printed for T. Osborne and J. Shipton, J. Hodges, J. Newbery, B. Collins, and S. Crowder and H. Woodgate, 1756

First edition

QK41 H6

Although John Hill was judged a quack by contemporaries, he made a great and lasting contribution in the area of botanical studies. An apothecary by trade, Hill’s initial interest in plants was utilitarian; he collected them for friends and used them to concoct herbal remedies. Hill undertook several large projects in plant classification, among them this work, a valuable taxonomic achievement useful to the scholarly botanist.

In The British Herbal, Hill described and gave the common use for some fifteen hundred plants of Great Britain and illustrated his text with seventy-five full-page copperplate engravings executed by several different artists.

The University of Utah copy is one of only a few known to have been colored. All seventy-five plates have had green watercolor applied. Fifty-two of the plates contain additional colors applied to at least some of the specimens on the page. Many of the plates are completely colored. All the coloring was done by hand.

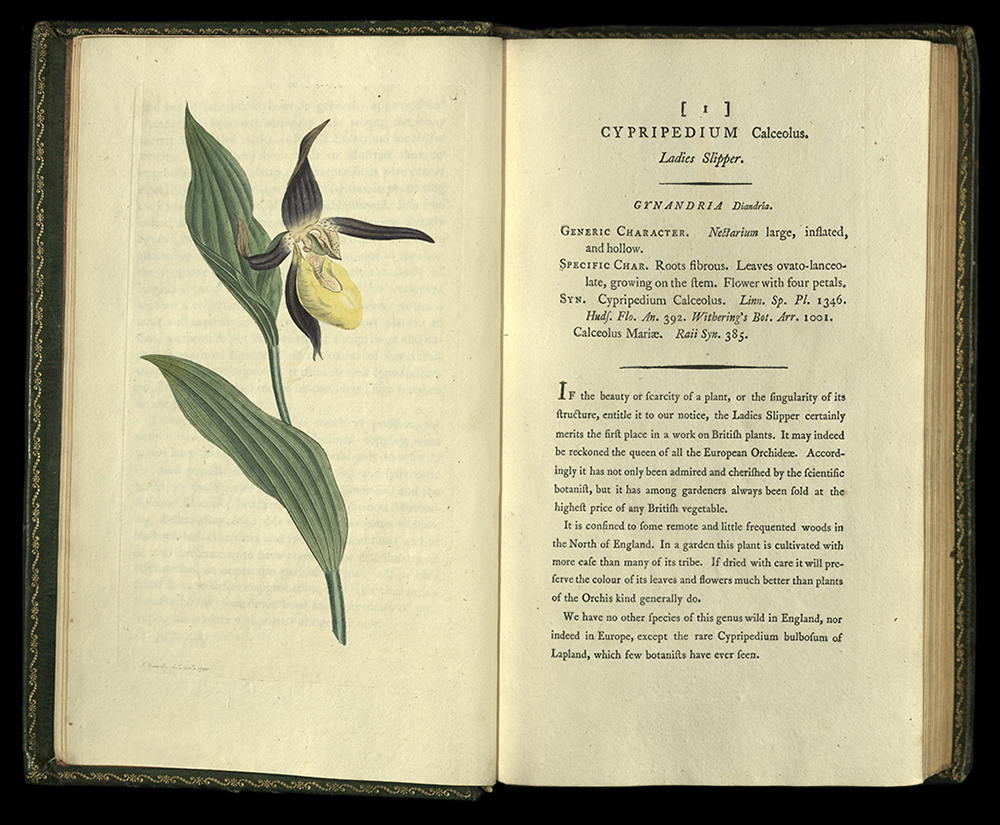

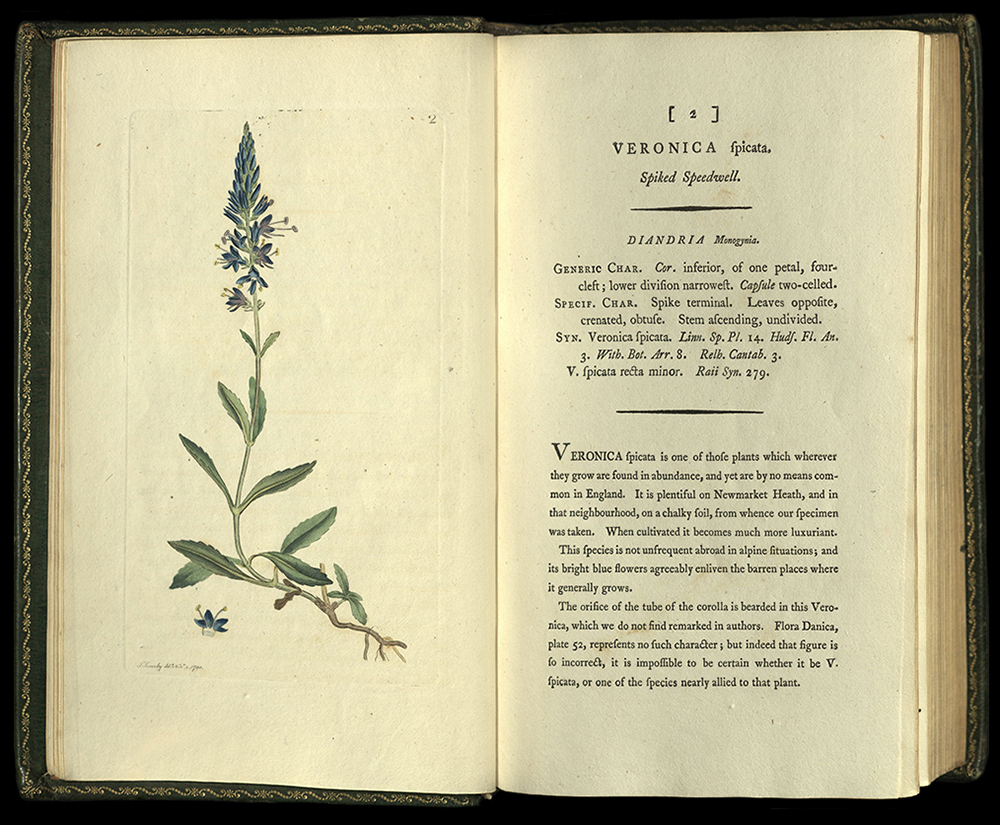

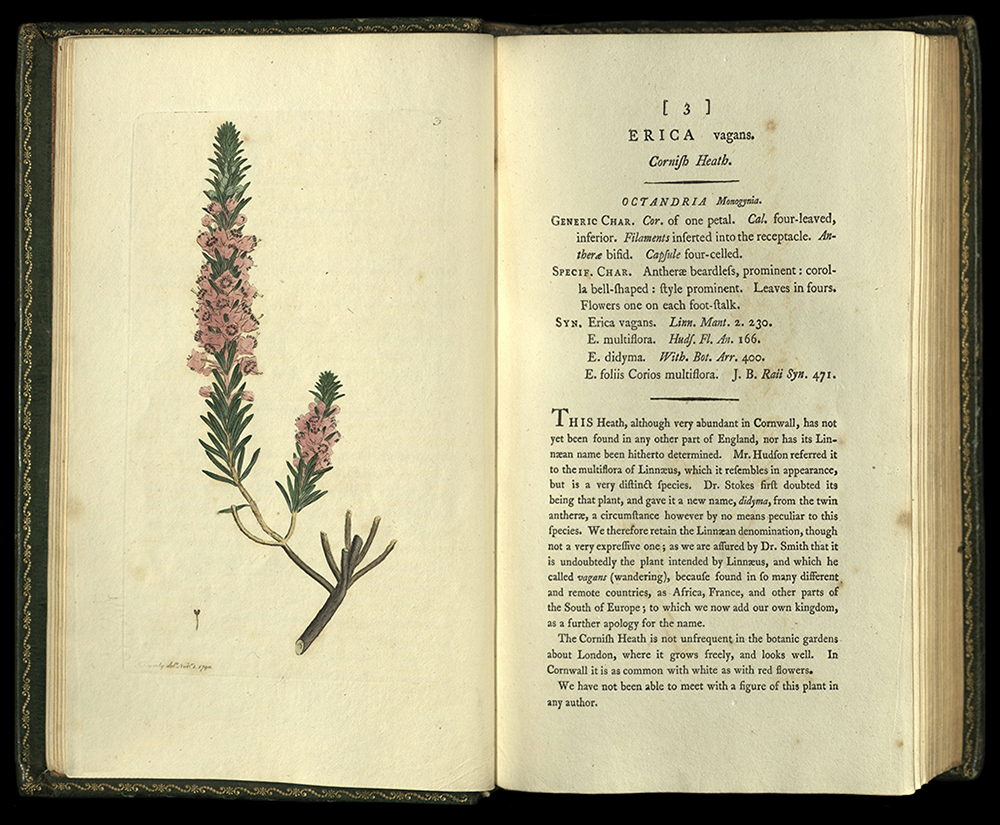

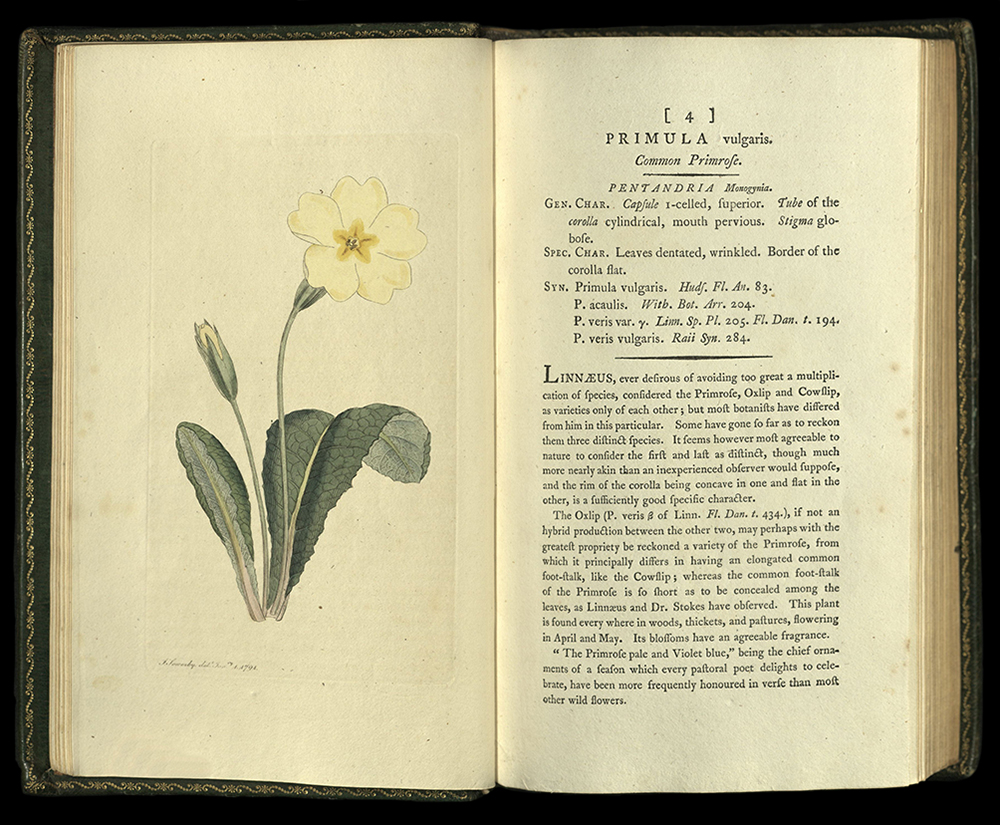

ENGLISH BOTANY ; OR, COLOURED FIGURS OF BRITISH PLANTS ...

James Sowerby (1757-1822)

London: Printed for the author by J. Davis, etc., 1790-1814

QK306 S73 vols. 1-36

James Sowerby studied painting at the Royal Academy in London. In 1790, he began publishing the first of his illustrated volumes of English botany, with the descriptions supplied by Sir James E. Smith. Issued in parts over the next twenty-three years, it was finished in 1814. The work is in thirty-six volumes with more than twenty-five hundred hand-colored plates.

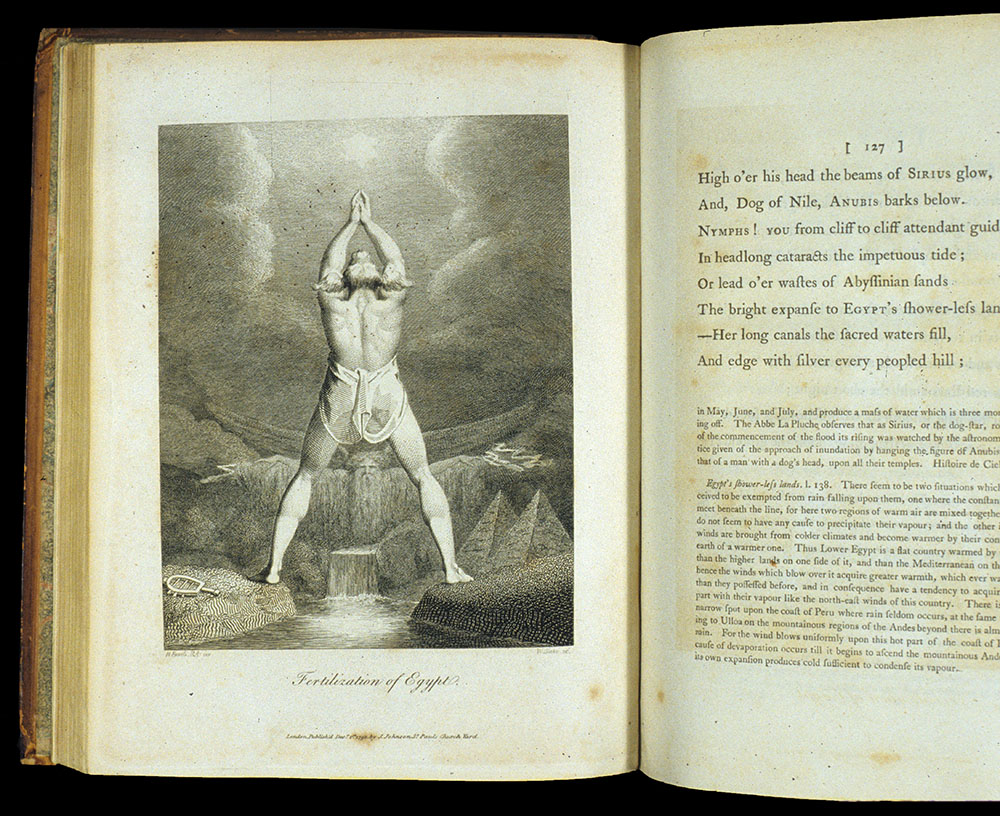

THE BOTANIC GARDEN

Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802)

London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1795

Third edition

PR3396 A7 1795 vols. 1 & 2

Erasmus Darwin was the grandfather of Charles Darwin. He was one of the leading intellectuals of eighteenth-century England, a respected physician, philosopher, botanist, naturalist, and inventor. He formed one of the first formal theories on evolution.

This long poem, The Botanic Garden, established Darwin as one of the leading English poets of his day – Coleridge called him “the first literary character of England.”

Some of the illustrations for this book were engraved by William Blake, after designs by Henri Fuselli.

FACSIMILE TEMPLE OF FLORA

Robert John Thornton (1786?-1837)

London: Collins, 1951

QK98 T5

This book is a fine example of Romanticism, full of richly colored, picturesque, and emotionally charged plates designed to appeal to an audience other than the scientist or even the gardener.

Robert Thornton had inherited a family fortune, leaving him time and energy to devote to an exotic and dramatic book production that he envisioned as superior to any other of its kind in scope, illustration, paper, and typography.

The great botanists of the day wholeheartedly approved of the project, among them Erasmus Darwin, whose poem The Botanic Garden certainly inspired the spirit of Thornton’s text. Thornton claimed that “Each scenery is appropriate to the subject,” and so, indeed, the symbolic and sumptuous backgrounds are – in a wild, sometimes amusing, and broadly sentimental way. In the end, the project depleted Thornton’s significant fortune.

Facsimile designed by Ruari Mclean. Color and collotype plates printed by Van Leer of Amsterdam. The text is set in Monotype Perpetua and printed by Meyer of Wormerveer on Van Gelder mould-made paper. The binding was produced at the London Craft Bindery of W.H. Smith and Sons. All but two of the plates were reproduced from the original copy held in Eton College.

The Rare Books copy once belonged to Estelle Doheny, the great book collector.

A NEW FAMILY HERBAL

Robert John Thornton (1786?-1837)

London: R. Phillips, 1810

QK99 A1 T56

As a young child, Robert Thornton kept his own garden. So enamored was he of the subject, that even as he was struggling with the publication his great Temple of Flora, and losing the family fortune while doing so, he continued to study and write about the plants he loved.

This comparatively modest work was illustrated by drawings engraved on wood by Thomas Bewick, considered one of the finest and most innovative wood engravers of the nineteenth century.