Relationships of Textiles and Text

Virtual Lecture for Fiber Liber

Curated by Lyuba Basin, 2023

Digital exhibition produced by Lyuba Basin, 2023

Fiber // Liber : RELATIONSHIP OF TEXTILES & TEXT

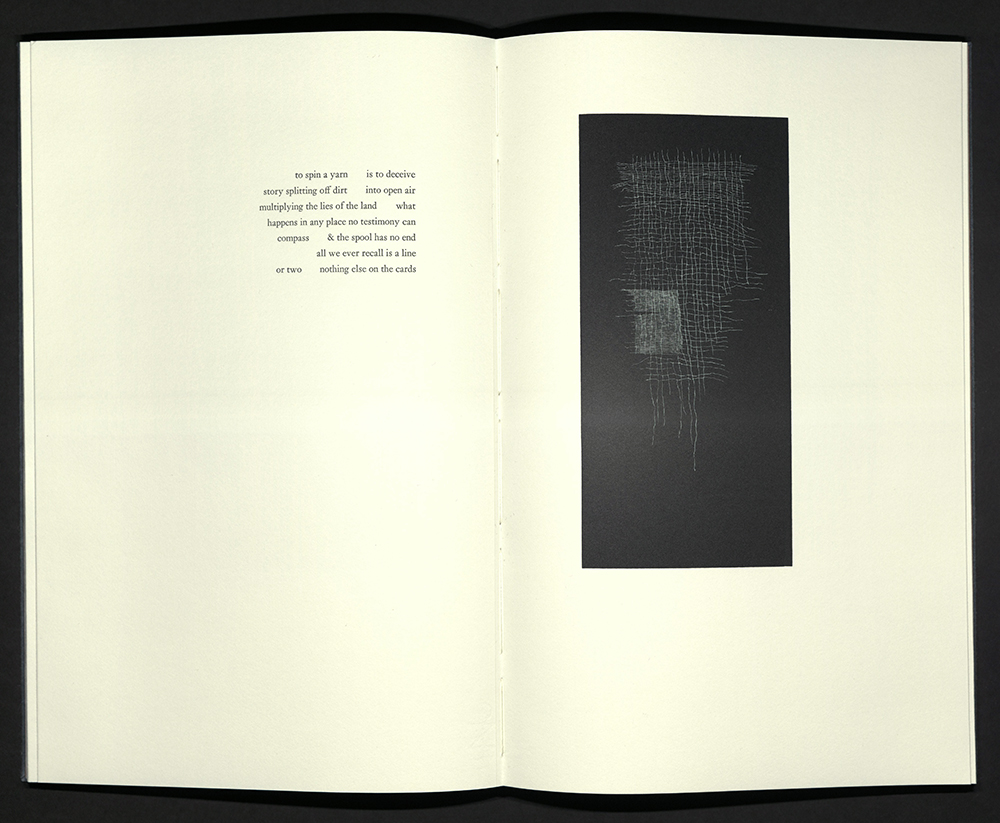

There is a clear etymological root between the words text and textile. We can trace it back to the Latin verb, texere — meaning to weave. The language of textiles provides us with certain figures of speech that bring a sense of materiality to writing. We weave a tale, spin a yarn, and piece together. There are stories that intertwine and threads that interlace. There are characters that get ensnared in a web of lies, there are ties that bind and relationships that fray. Material and immaterial. Textile and text.

Both have served as transmitters of cultural ideas. They have been linked to the sacred — to origin stories, prayers, songs, life cycles, mythmaking, and storytelling. Both are made from stems, roots, fibers, whether beaten or spun. In some cases, textile evolves into text, as the fabric that was once created by workers in a textile mill eventually becomes rags in a paper mill. Textile to text.

If we look closely, the book itself is nothing more than a form of fiber art. From paper to sewn binding to cloth covers, the book is the perfect example of the interwoven industry of textiles and text. Fiber Liber is a commentary that seeks to explore that relationship.

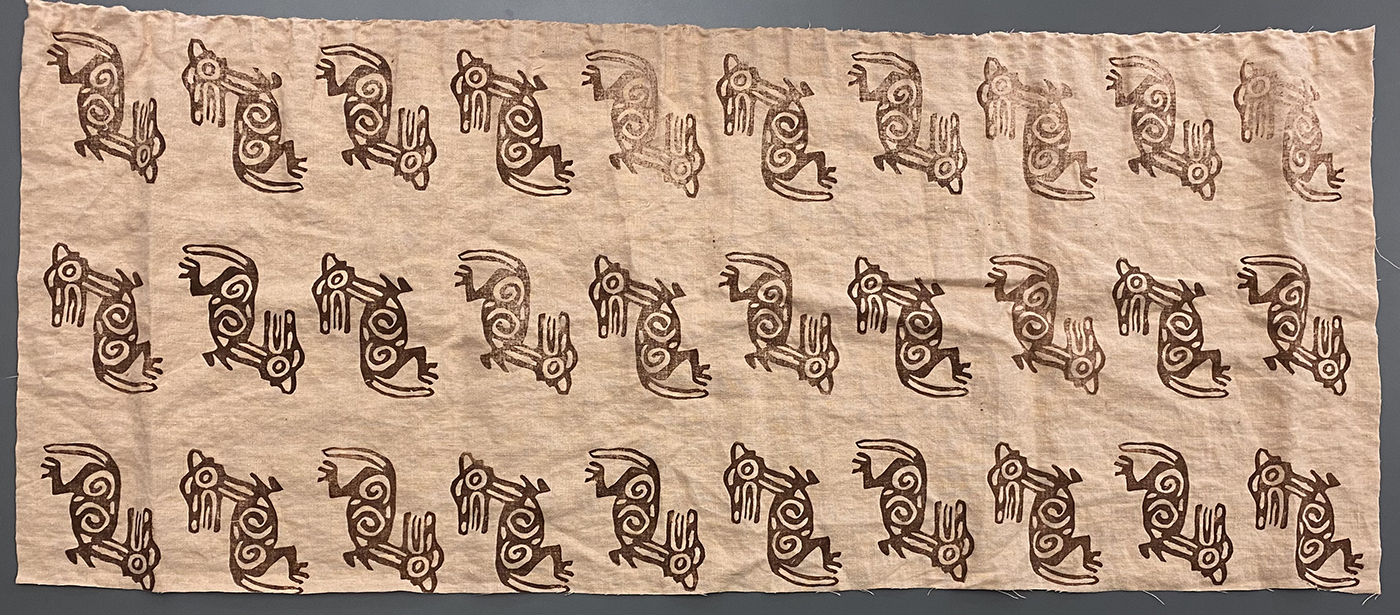

CLAY STAMP WITH JAGUAR DESIGN

Eighth century (realia)

NK9504 C53

Ceramic stamps were made in Central Mexico from the Early Formative period (ca. 1800-1200 B.C.) and continued into the early sixteenth century. It is assumed that the earliest examples of such objects functioned as ornamental devices used to decorate clothing, ceramic vessels, and even the body. They typically feature abstract geometric designs or stylized animal imagery, often in repeating patterns. Commonly found interred with human remains, these stamps were apparently valued as highly in death as they were in life.

The representation of jaguars in Mesoamerican cultures has a long history, with iconographic examples dating back to at least three thousand years. All major Mesoamerican civilizations prominently featured a jaguar god, and for many the jaguar was an important part of religious practice. For those who resided in or near the tropical jungle, the jaguar was well known and became incorporated into the lives of the inhabitants. The jaguar's formidable size, reputation as a predator, and its evolved capacities to survive in the jungle made it an animal to be revered. The Olmec and the Maya witnessed this animal's habits, adopting the jaguar as an authoritative and martial symbol, and incorporated the animal into their mythology, particularly that of the underworld.

This Mayan artifact was used for decorative stamping of fabrics and ceramics, and for printing on huun, or fig bark, paper. The ceramic stamp features a jaguar design, with spiraling lines defining its spots.

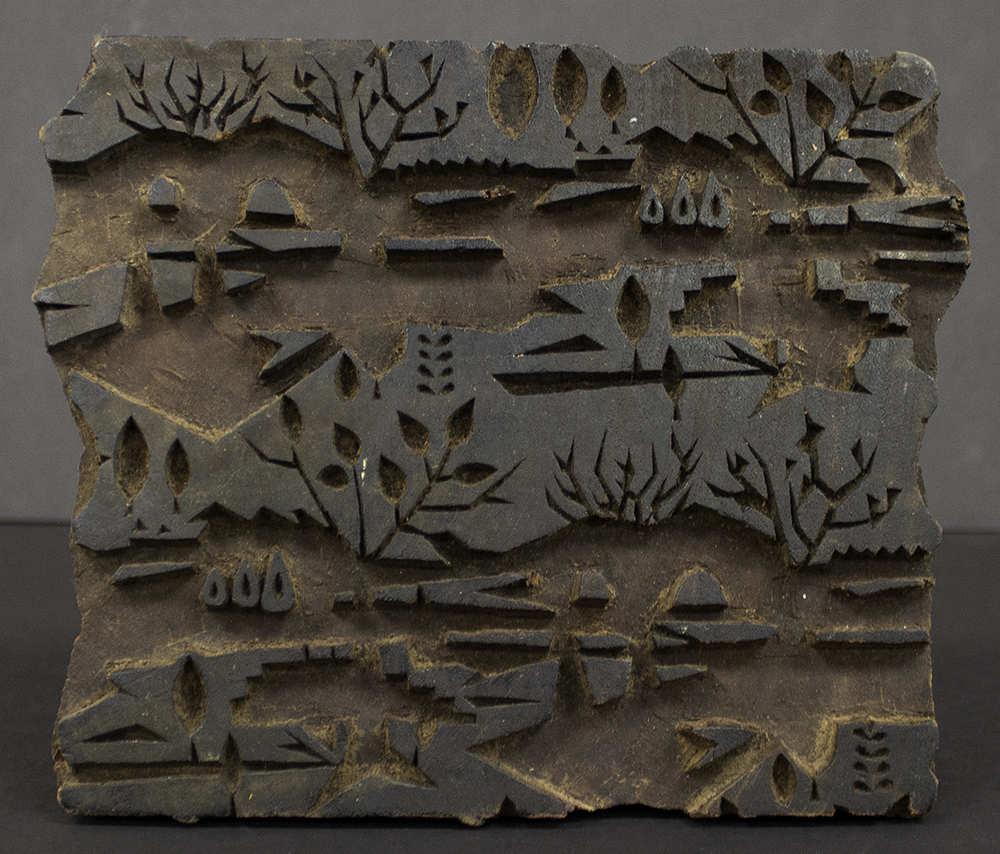

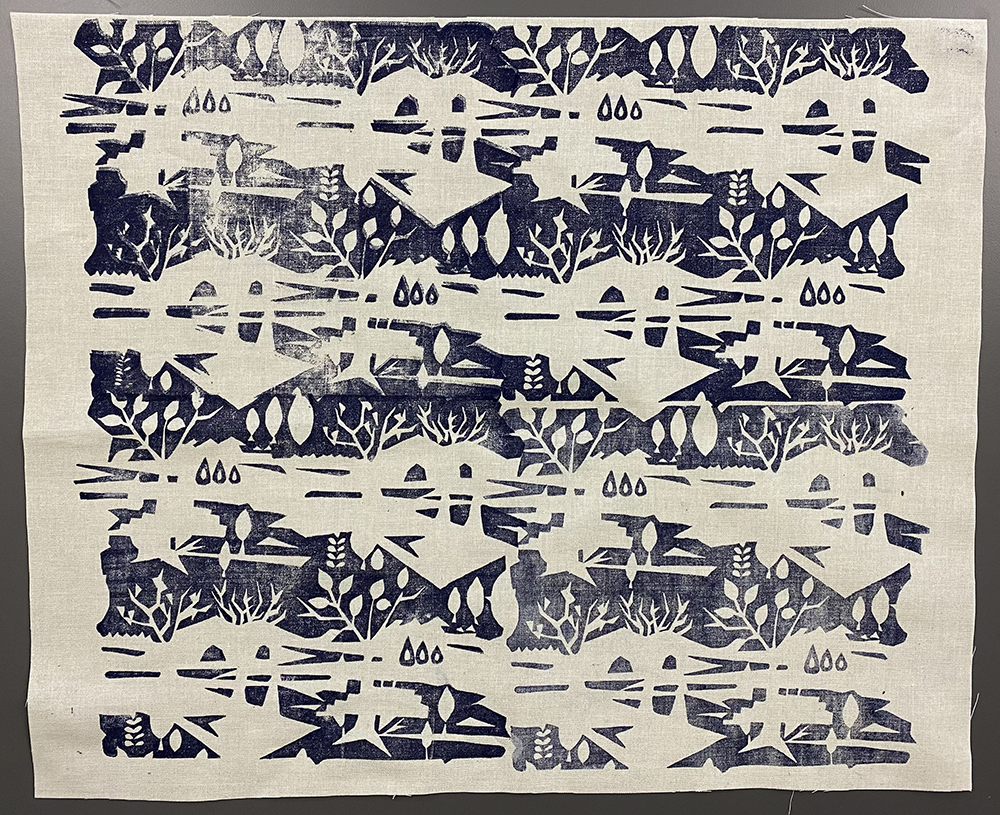

WOOD BLOCK FOR PRINTING CLOTH OR WALLPAPER

Nineteenth century (realia)

NK9504 W66

Woodblock printing on textiles is the process of printing patterns on various fabrics, usually of linen, cotton or silk, by means of carved wooden blocks. It is the earliest and slowest of all methods of textile printing. Despite being a slow process, woodblock printing is capable of yielding highly artistic results, some of which are unobtainable by any other method.

The origins of woodblock printing date back several thousand years, with early examples attributed to ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Museum specimens, however, establish the fact that pattern printing on textiles had become a developed industry in parts of Europe by the end of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth century. The first written reference to printed textiles in Europe can be found in Florentine trade regulations from the fifteenth century. In 1437, Italian painter Cennino Cennini published a treatise titled Il libro dell'arte, in which he describes the technique.

Wood used for textile printing may be made of box, lime, holly, sycamore, plane, or pear wood. Although they may vary in size considerably, they must always be at least two to three inches thick, otherwise they are liable to warping. The block, being planed smooth and perfectly flat, has the design drawn upon or transferred to it before it is readied to be carved out.

This nineteenth-century woodblock was received by the rare books collection with bindery equipment purchased from Colton and Nancy Storm in November 1977.

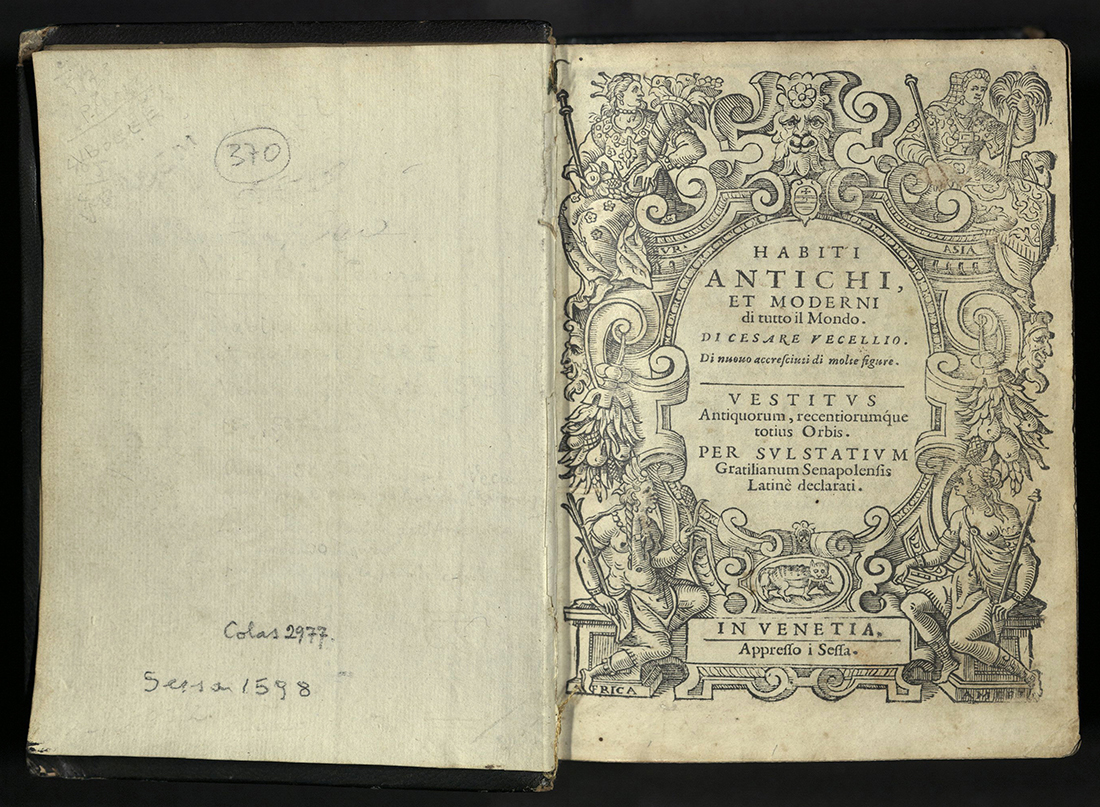

HABITI ANTICHI ET MODERNI DI TUTTO IL MUNDO

Cesare Vecellio (1521-1601)

Venice: Appresso Gio. Bernardo Sessa, 1598 Second edition

GT509 V43 1598

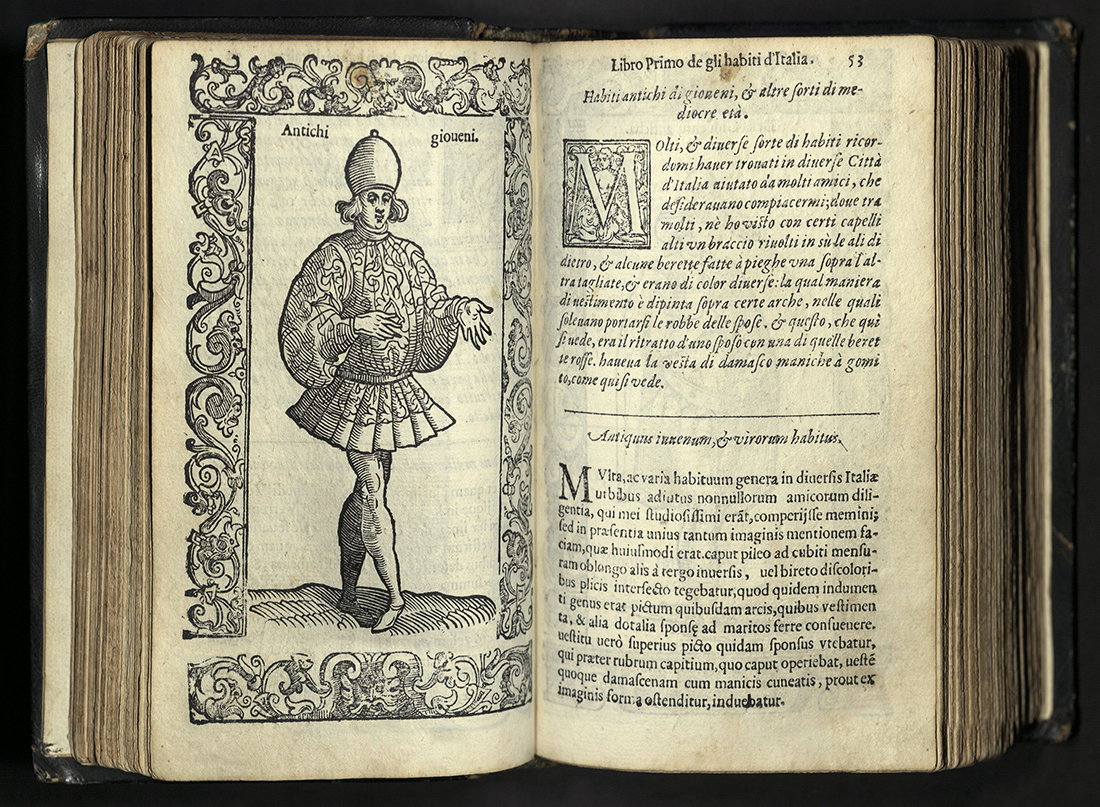

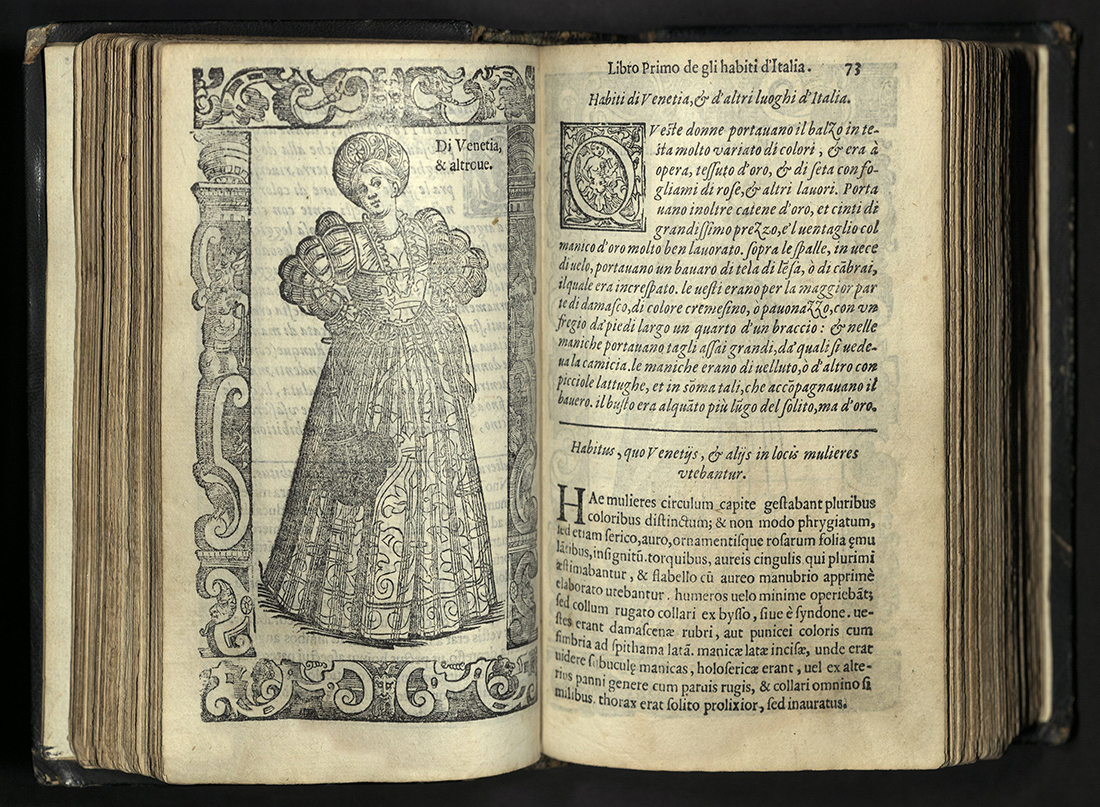

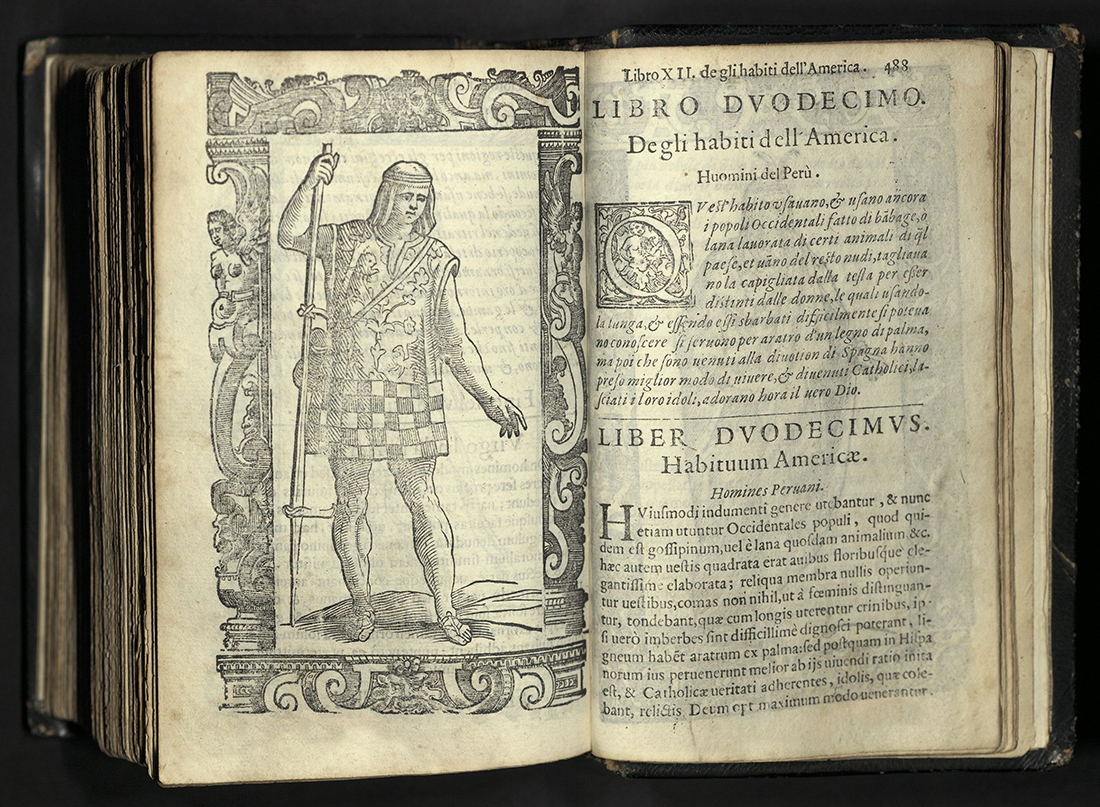

The sixteenth century saw the rise in popularity of the “costume” book. Between 1520 and 1610, more than two hundred collections of engravings, etchings, or woodcuts concerned with clothing or personal adornment had been published. These books reflected not only the great wealth of the mercantile classes, but also the enormous wave of travel and exploration in search of markets and raw materials. Pehaps the best known of all, and in many respects the apex of the century’s achievements, was that of Cesare Vecellio. The first edition of Vecellio’s costume book was printed by Damian Zenaro in Venice in 1590, with the title De gli Habiti Antichi et Moderni di Diverse Parti del Mundo. It was an immediate publishing sensation. For the first time, a book had brought together vivid descriptions and accurate depictions of world costume throughout history. Aimed, in part, at artists who might use it as a pattern book, its appeal soon proved to be more widespread. The book recognized that clothing was as much an identifier of rank as it was “fashion” — constantly changing, crossing borders, and transforming the way people lived.

In early-modern Europe, ethnographic curiosity was channeled into books on clothing. Clothing wasn’t merely an expression of personal style or an imitation of fast-changing fashion. Clothing marked gender, age, marital status, economic rank, and regional identity. Unlike today, individuals were not free to dress as they pleased. In Venice and other European cities, sumptuary laws controlled the fabrics, colors, and the cut of clothing in attempts to limit inequality among citizens. To dress was to be invested with a public identity, according to a system of fixed codes. In a largely pre-literate society, people learned to read the value of textiles and the meaning of their cut as signs of profession, wealth, social status, and geographical provenance.

The second edition of Vecellio’s costume book, Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il mondo, was printed in Venice by Giovanni Bernardo Sessa in 1598. In this edition, Vecellio omitted the majority of his introductory historical text and shortened his captions considerably, so that the illustrations now appeared on every verso page, with each facing recto occupied by a brief Italian text at the top, and a newly prepared Latin translation at the bottom. More importantly, the number of illustrations was increased to five hundred. The carefully drawn woodcuts show the costumes of the world known in Vecellio’s day: Italy, France, the Lowlands, Burgundy, Spain, Portugal, Scandinavia, the German lands, the Slavic lands, Hungary, the Balkans, the Aegean, North Africa, Arabia, Syria, Armenia, Persia, India, China, and the recently discovered New World, including indigenous tribes of Roanoke, Florida, Mexico, and Peru. The twenty images of American costume were derived from various travel accounts.

Derived from the Latin habitus, or aspect, the word "habiti" signified the ways in which apparel invested bodies with meaning through the quality of the fabric and the tradition and conventions attached to dress.

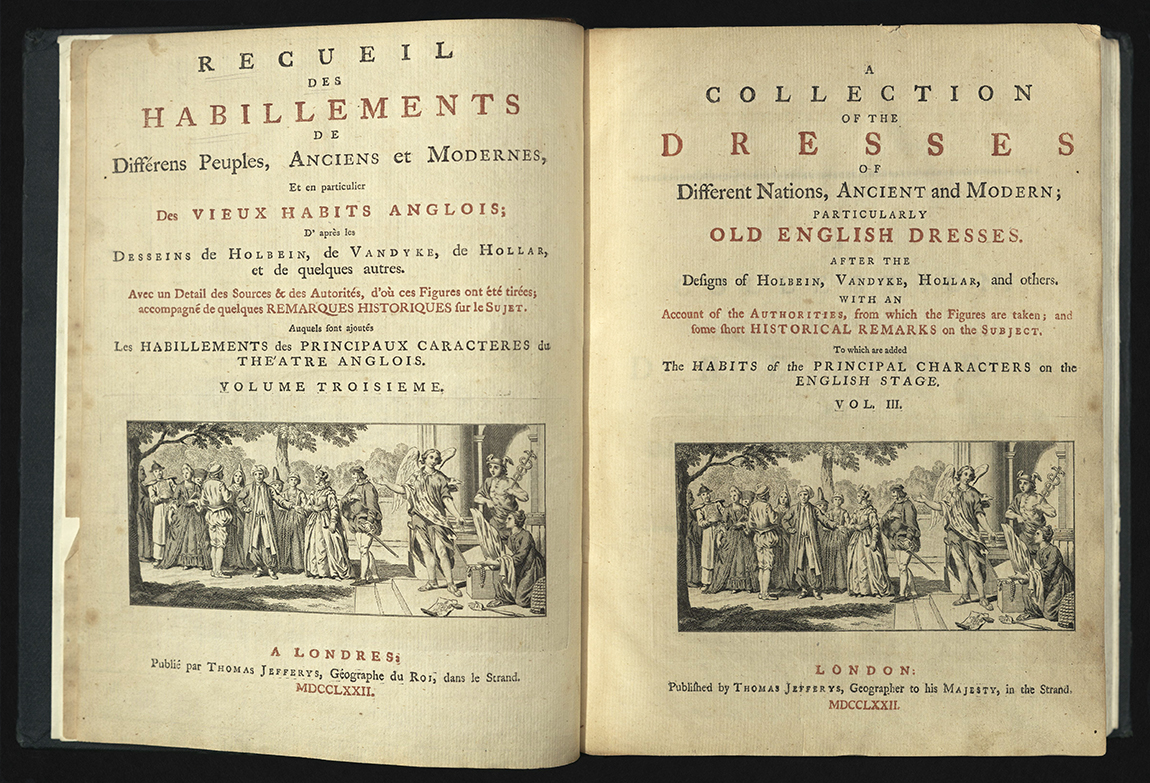

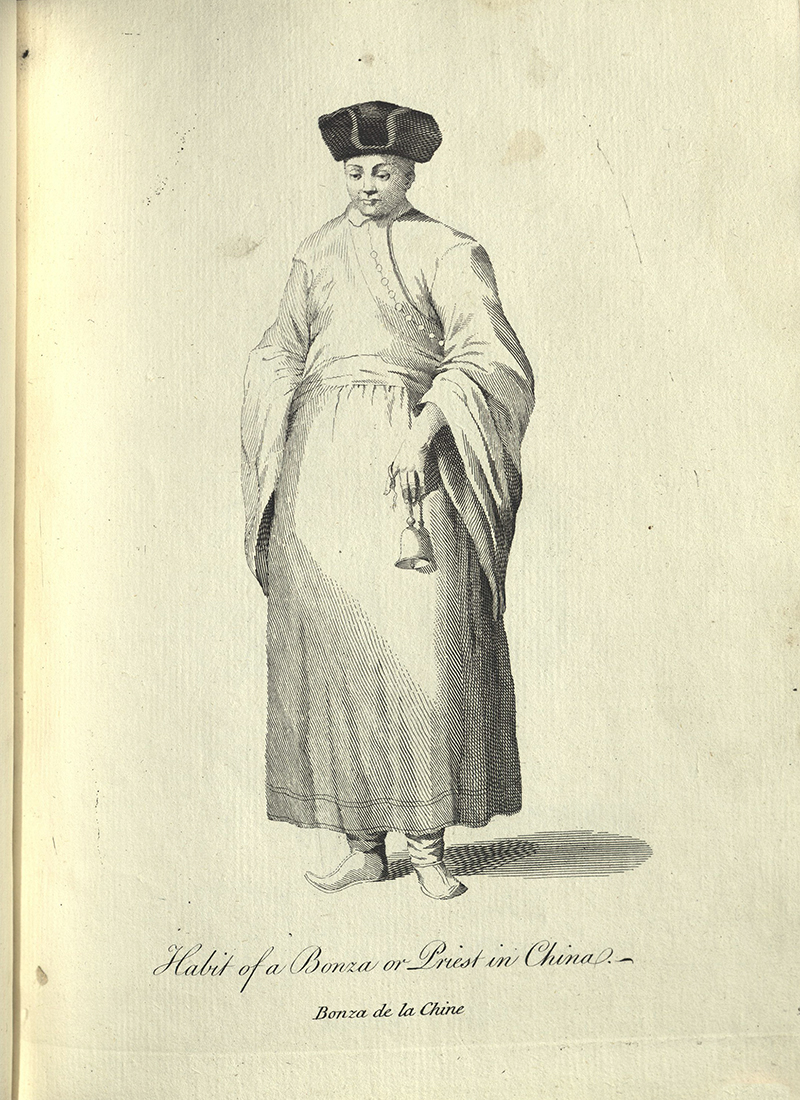

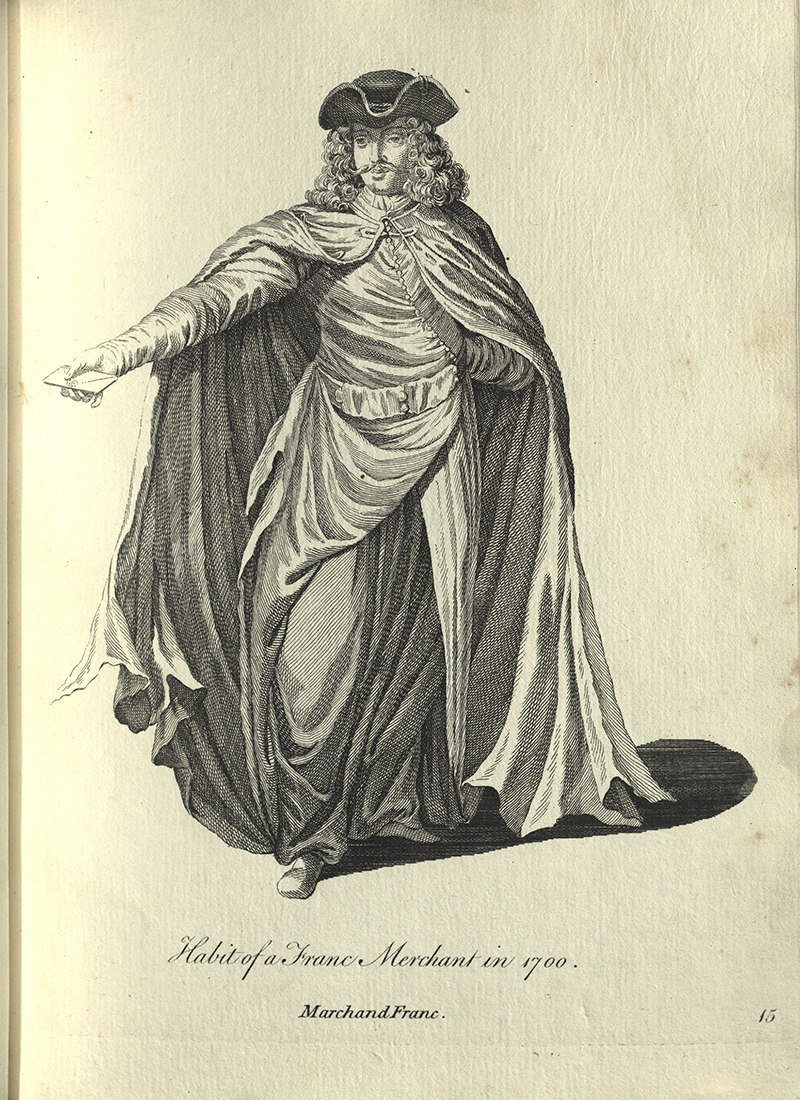

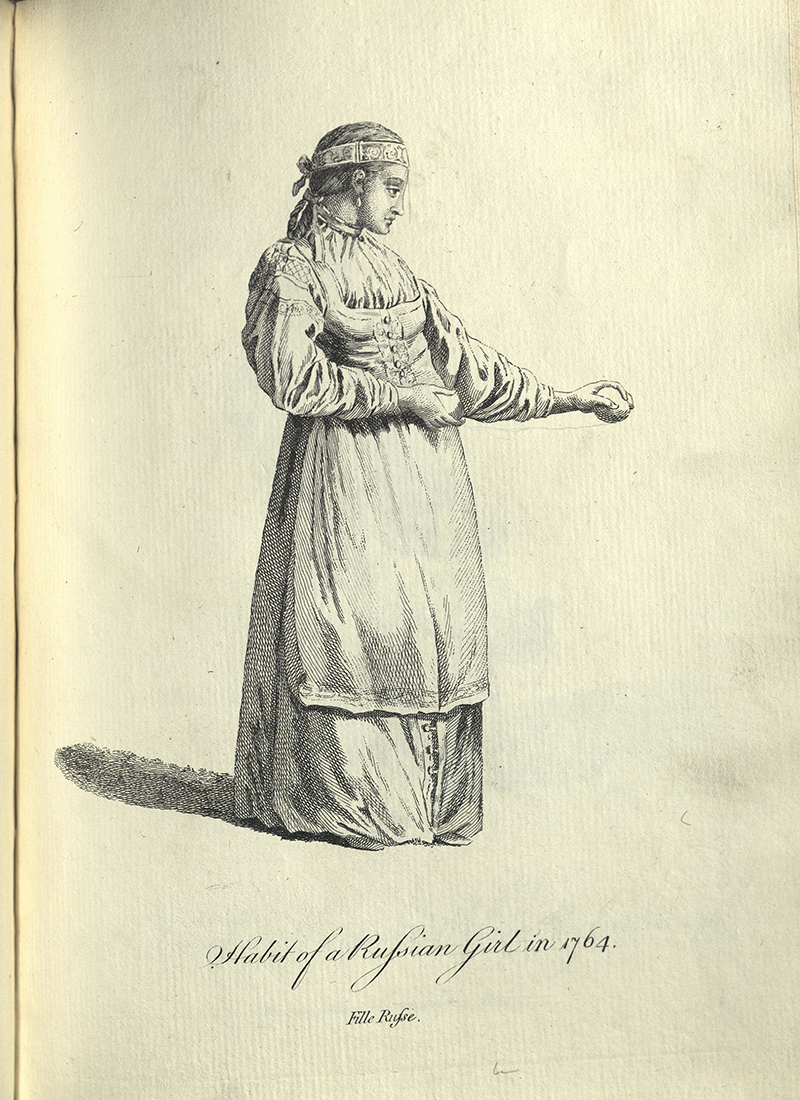

A COLLECTION OF THE DRESSES OF DIFFERENT NATIONS

London: Thomas Jeffreys, 1757-1772

GT513 C6

The costume book tradition continued well into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In addition to being visually enticing, they were also educational. In a sense, costume books are a form of ethnographic studies — used to understand cultures all across the world. It should not surprise us, then, that cartographers would excel at compiling the latest fashion trends.

Thomas Jefferys was a prolific map publisher, engraver, cartographer, and geographer to King Georges III. Based in London, Jefferys was apprenticed to Emanuel Bowen, a prominent mapmaker and engraver. Throughout his career, Jeffreys worked with several collaborations. His first atlas, The Small English Atlas, was published with Thomas Kitchen in 1748-1749. The following decade, he went on to publish several maps of North America.

Jeffrey’s costume book, A Collection of the Dresses of Different Nations, offers a comparative study of costumes from the Renaissance up to 1750, and features the designs of Hans Holbein, Anthony van Dyck, and Wenceslaus Hollar. The work also draws on several earlier publications. Among the books cited as sources are those by Charles de Ferriol, Johann Christoph Weigel, Athanius Kircher, Jean-Baptiste Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste Le Prince, Jean-Baptiste Chappe d'Auteroche, Filippo Bonanni, and Cesare Ripa.

Four volumes were issued between 1757-1772. Each volume introduces the plates with “A Description of the Habits” with text and plate captions printed in English and French. University of Utah rare books copy is volume 3.

MINUTES OF EVIDENCE... FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE HEALTH AND MORALS…

Great Britain Parliament, House of Lords

London: 1819

HD8039 T42 G75 1819

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Great Britain became the first country to industrialize. Because of this, it was also the first country where the nature of children’s work changed so dramatically that child labor was soon considered a social problem and a political issue. Children of poor and working-class families had worked for centuries prior to industrialization. The practice of putting children to work was first documented in the Medieval era where they performed a variety of tasks that were auxiliary to their parents, but critical to the family economy. While hours varied from trade to trade and family to family, children usually worked twelve hours per day, with time out for meals and tea. These hours, moreover, were not regular over the year or consistent from day-to-day. This form of child labor was not viewed by society as cruel or abusive but was accepted as necessary for the survival of the family and development of the child.

Once the first rural textile mills were built in 1769 and child apprentices were hired as primary workers, the connotation of “child labor” began to change. These child apprentices were paupers taken from orphanages and workhouses and were housed, clothed and fed but received no wages for their long day of work in the mill. Reformers called for child labor laws and, after considerable debate, Parliament took action and set up a Royal Commission of Inquiry into children’s employment. The three laws which most impacted the employment of children in the textile industry were the Cotton Factories Regulation Act of 1819, which set the minimum working age at nine and maximum working hours at twelve; the Regulation of Child Labor Law of 1833, which established paid inspectors to enforce the laws; and the Ten Hours Bill of 1847, which limited working hours to ten for children and women.

The British Parliamentary Report, published in 1819, concluded that children formed a substantial part of the labor force in the textile mills. They calculated that while only 4.5% of the cotton workers were under ten years old, 54.5% were under the age of nineteen — confirmation that the employment of children and youths was most pervasive in cotton textile factories.

Since the age of Louis XIV, Paris had been known as a fashionable place. By the turn of the twentieth century, however, it would become the “fashion capital” of the world. During the reign of Louis the XIV, the industry of luxury goods came increasingly under royal control. The French Royal Court, in turn, quickly became the arbiter of taste and style in Europe. While Louis XIV was hailed as a patron of fashion, he had little to do with its spread and proliferation. Rather, the rise of French fashion could be credited to the development of the “fashion press” in the early 1670s and the publications of Jean Donneau de Visé — a notable journalist, historian, playwright, publicist and founder of the literary, arts, and society gazette, Le Mercure Galant. Access to printed materials transformed the French fashion industry by marketing designs to a broad public outside the French court while also popularizing notions such as the fashion "seasons" and changing styles.

PROMENADE DE LONGCHAMP, OPTIQUE NO. 4

Paris: ca. 1810-1827

Z1033 T68 O68 1827

The Promenade de Longchamp was an annual social event which took place on the Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday of Holy Week every spring along the Champs-Élysées and through the Bois-de-Boulogne. The tour ended at the abbey of Longchamp, where the nuns sang the office of Tenebrae, a village four miles from Paris. A convent there, established in 1256, had long been a destination for religious pilgrims.

In the late seventeenth century, the pilgrimage became an unauthorized secular spectacle. The nun's choir was fortified with singers from the Paris Opera. The theater in Paris was closed during Lent, which made the Promenade one of the few ways in which high society could flaunt their new spring fashions. A procession of people in festive costume traveled on horseback, in carriages, and on foot. Wealthy citizens of Paris vied to have the most elaborate carriages and clothing, while the lower classes, including laborers, soldiers, and prostitutes, lined the route to gawk. Police turned out in force, to keep the parade participants safe. The Paris Archbishop de Beaumont tried to halt the parade by ordering the convent closed during Holy Week. The parade did not stop. Participants were there to see and be seen.

In 1789, the Promenade was disrupted by an angry mob. The convent, by then wholly peripheral to the show, was closed by the Revolutionary government.

Napoleon revived the parade in the nineteenth century, in part as a way to bolster the fashion industry, but the later parades did not match the lush grandeur of those in the eighteenth century. Still, the parade contributed to later fashion phenomena. The American "Easter Parade" and the big, ostentatious hats of the Kentucky Derby can be traced back to the Promenade de Longchamp.

This early nineteenth century, concertina-style peepshow depicting the Promenade de Longchamp in Paris is etched on the front and back panes and contains four cut-out sections in-between, all hand-colored. The front panel has a circular viewing aperture. It is housed in its original marbled paper slip-case with engraved label.

The extravagant styles of the French Royal Court racked up enormous debts to keep up the pace of the changing styles. Such shopping sprees notably ruined the reputation of Marie Antoinette and were one of the many factors that led to the peasant’s revolt and the French Revolution. Despite the negative connotations, the textile industry was booming by the end of the eighteenth century and greatly influenced the gross domestic product rates in France. The spike in consumerism had been fueled by an overwhelming interest in high fashion, which often surpassed the boundaries of socio-economic class and rank. Particularly in Paris, women began purchasing knock-offs of luxury items customarily worn by the elite. These fashion accessories included watches, buttons, and belt buckles.

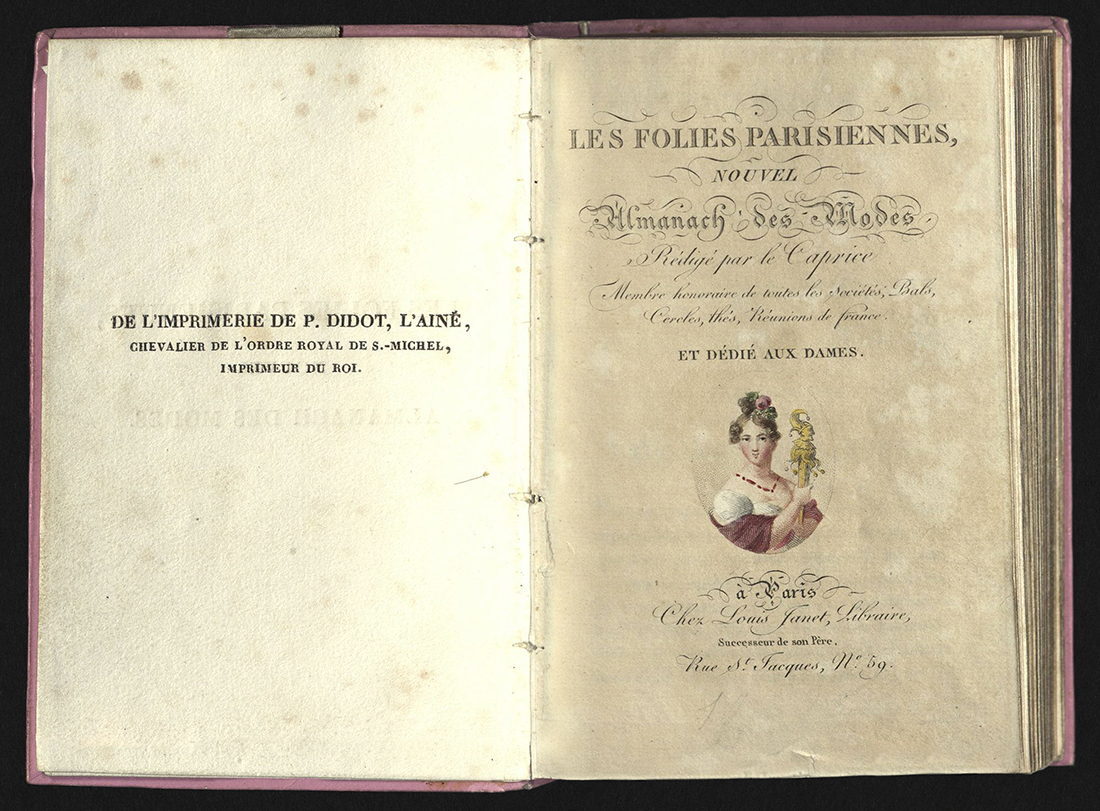

LES FOLIES PARISIENNES, NOUVEL ALMANACH DES MODES...

Caprice

Paris: Chez Louis Janet, 1823

GT871 F65 1823

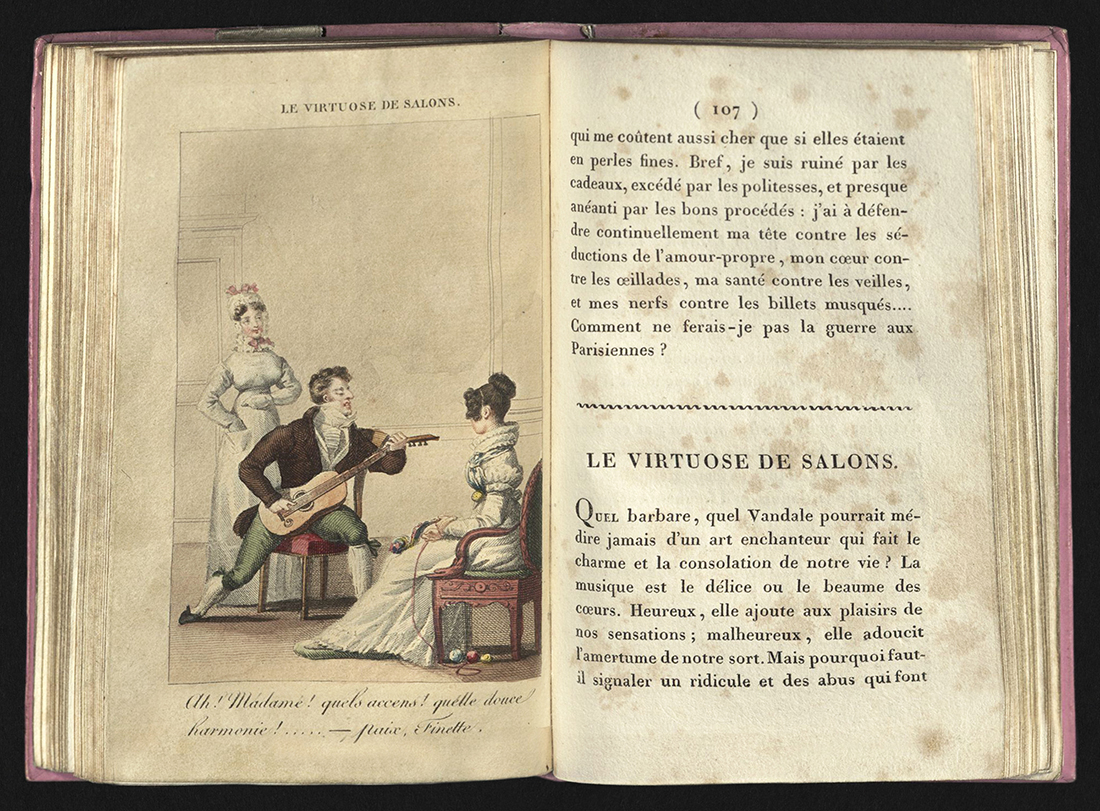

Written by Caprice, “honorary member of all Societies, Balls, Circles, Teas, Meetings of France...” this almanac, which was “dedicated to Ladies,” connects textiles to text with a collection of poems about material goods such as gloves and hats, as well as short essays on the art of wearing a tie, the corset, and court attire. With five colored illustrations, Les Folies Parisiennes is a rare satirical collection directly from the fashion capital.

Published by Louis Janet and printed by Pierre Didot, this book reveals the intersection of the book trade with the textile industry. Pierre Didot the Elder was among the third generation of a French publishing dynasty renowned for the impeccable beauty and quality of their books. The Didot firm embraced the highest standards of bookmaking, and its patrons included King Louis XVI and his brother, the future King Charles X. Pierre Didot’s good fortune during the French Revolution was exceptional, especially at a time when many such printers lost their presses, their homeland, or worse, their lives.

During and after the French Revolution, there was a distinguishable shift in fashion styles, particularly among the common and lower classes, a great many of whom had become radical and militant partisans in response to their poor quality of life. In opposition to the word “aristocrat” they called themselves the San-culottes, referring to their clothing and thus their lower-class status. Culottes were the fashionable silk knee-breeches worn by nobility and bourgeoisie. On the other hand, the working class were sans-culottes (without breeches) and wore pantaloons, or long trousers, instead. They rejected the powdered wigs and favored natural hair and informal styles.

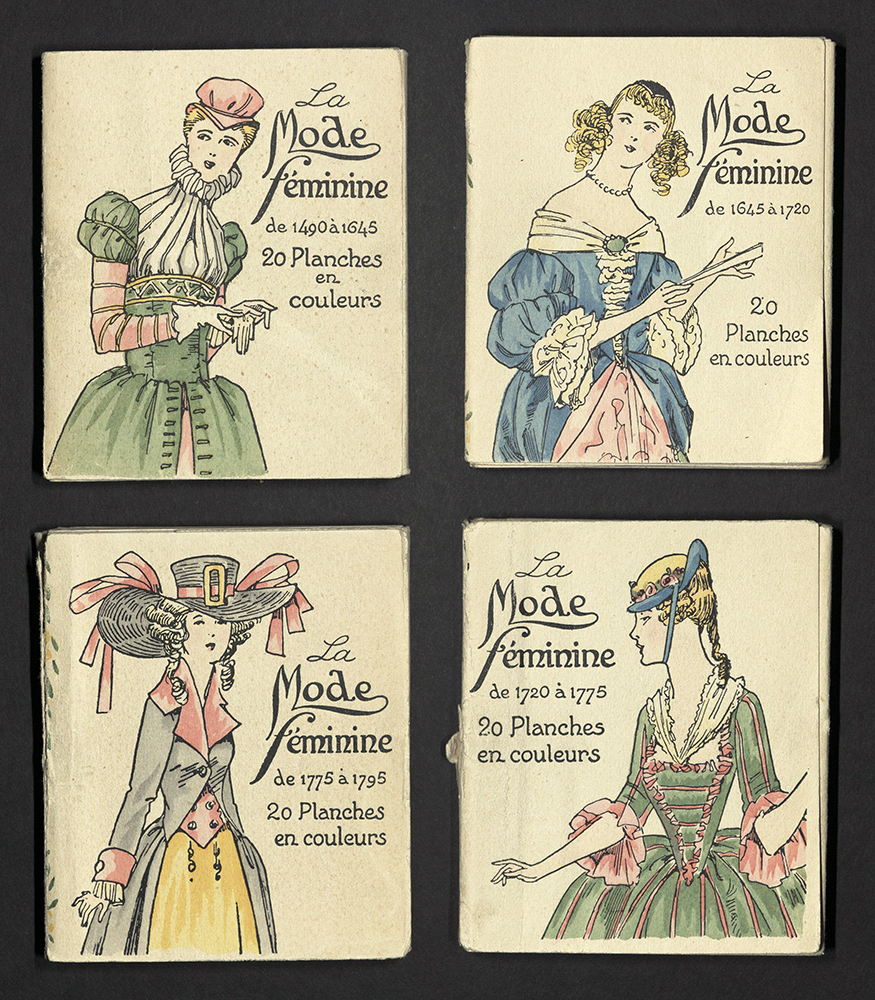

LA MODE FEMININE: DE 1490 A 1795

Paris: Editions Nilsson, [1920s]

GT1720 M69

An illustrated history of French fashion can be found in collection of four miniature books titled, La Mode Feminine. Each booklet features twenty hand-colored prints revealing the evolution and style of women’s clothing from 1490 to 1795. Printed by Editions Nilsson sometime in the 1920s, during the Belle époque, when Paris laid claim to its title of fashion capital.

Libraire Nilsson was a French publishing house founded in Paris in 1885 by Karl Nilsson and Per Lamm. The publishing house specialized in illustrated books, producing bound art albums, popular novels, and classics of world literature. For his illustrations, Nilsson called on artists such as René Binet, renowned for his Art Nouveau style.

WEAVING

Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852)

Circa 1880s

LB1542 F76 1880

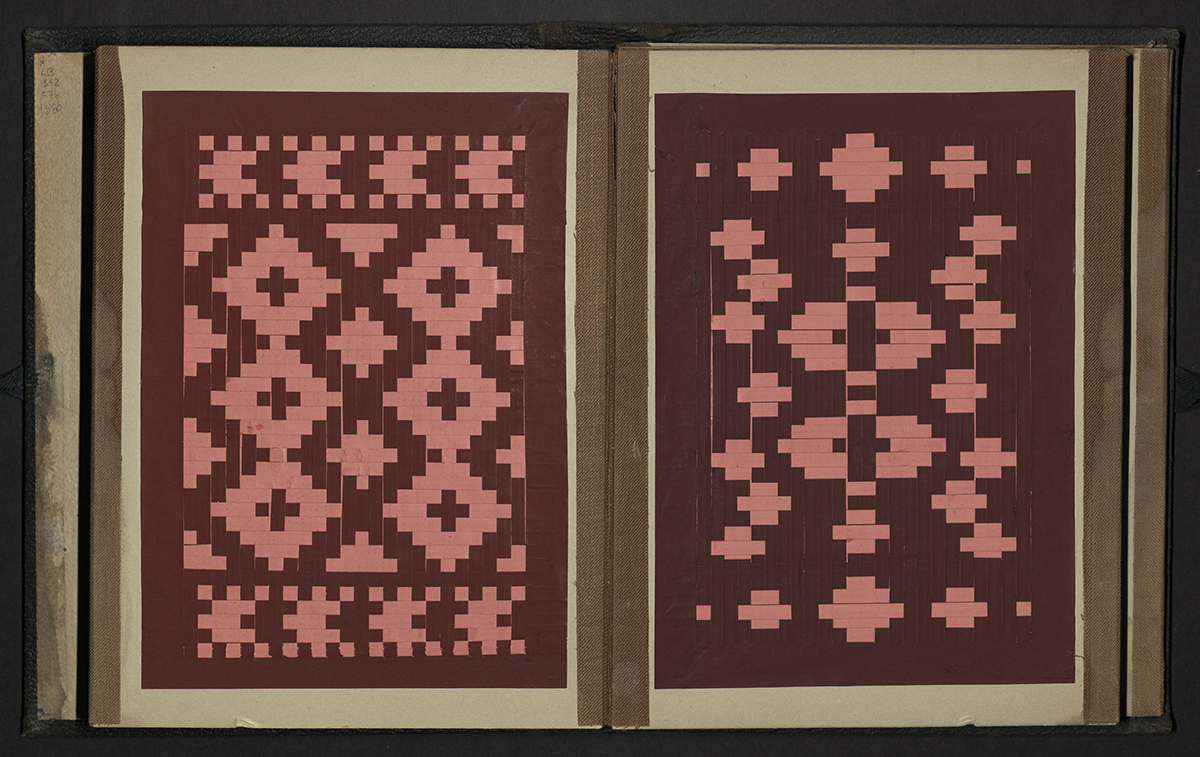

Friedrich Froebel, a German educator, is best known as the inventor of the kindergarten system. Froebel’s kindergarten was the most successful system for teaching children about art, design, mathematics, and the natural world. In the 1840s, he devised the idea of twenty occupational “gifts” for children, some of which included sets of blocks, stick work, rings, drawing exercises and paper weaving. Gift number 14 was "Paper Weaving." Many albums such as this were compiled in the nineteenth century as teaching aids for use in kindergartens in Europe and North America. With their intricate patterns, albums of this sort are seen by some as precursors to the abstract design movement in art of the twentieth century, recognized in the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mondrian, Braque, Le Corbusier, Albers, and R. Buckminster Fuller.

Produced around 1880, this book contains fifteen 7x5 pages of red and pink paper woven into various geometric patterns mounted on heavy cardboard leaves in an accordion-fold structure with cloth-lined gutter and outer margins. The book is housed in an original folding case of black cloth-covered boards ruled in blind with the world “Weaving” stamped in gilt on the front board, with black ties.

[SAMPLE BOOK]

TS1124 S35 1900z

Sewing samplers taught young girls and women the tactile pedagogy of stitches. The history of the sampler is thought to date back to the early modern period, but few examples remain. Interest in collecting needlework samplers has increased greatly in the last several decades, no longer seeing the work as nostalgic folk art, but a tool for understanding the past and investigating the social and cultural history of manufacturing and design.

Samplers often included embroidered sayings, maps, family trees, multiplication tables, calendars, poetry, prayer and hymns, as well as alphabets. By the period of the Centennial Exposition in 1876, the American sampler underwent dramatic changes. Rather than exemplars of embroidered cloth, punched-paper patterns for samples became available. These had the design already marked out on heavy paper, with holes punched for embroidery wool to slide through. They were sold in a variety of patriotic and sentimental motifs and phrases.

While older samplers were probably made by adult women, eighteenth and nineteenth century, were likely made by young girls — as samplers became less about keeping a working record of stitches and more about proof of a basic skill and part of their domestic education.

This sampler was owned by Hattie D. Squier, the great-granddaughter of Alexander Kirkpatrick, a minute-man of the American Revolutionary War, in the Somerset County, New Jersey Troops. The sampler was then passed down to her daughter, Edith, whose signature can also be found on the first page of the book. Edith Squier Mudgett was born on February 7, 1888 in Nebraska. She married Harry David Hines on April 21, 1920 in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Since the sampler was a direct personal link with past generations, often signed by grandmothers and great-grandmothers, it was much more likely to be kept than other material objects like cookware or furniture. Samplers were almost certain to be passed down in the family, and in the instances that they were given away, they were much more likely to be donated to museums, or libraries such as ours, to be kept as a historical record.

Looking at such training samples, one gets a sense of a sort of bilingualism — a fluency in the visual and the verbal, something sewn and something printed. A dual language that often only women could speak.

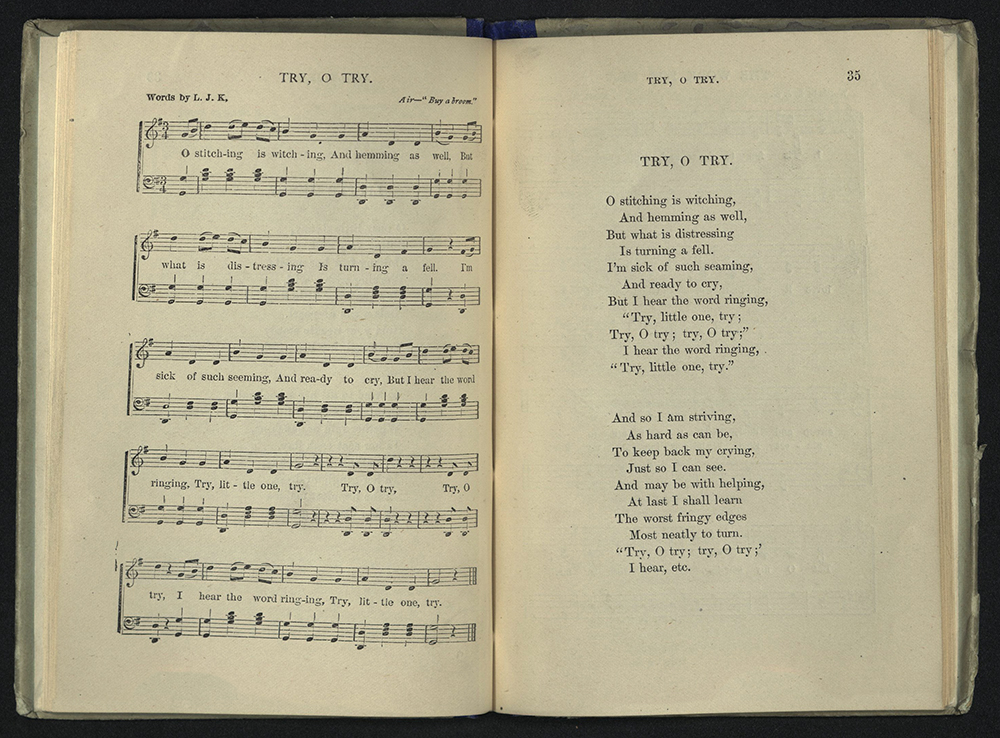

ILLUSTRATED SEWING PRIMER: WITH SONGS AND MUSIC

Louise J. Kirkwood

New York: Wynkoop & Hallenbeck Printers, 1881

TT710 K58 1881

The demand for textiles has gone hand-in-hand with historical technological innovations — from the spinning jenny, the cotton gin, the Jacquard machine and the factory system. In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution saw the development of new weaving machines at precisely the same time that changes in printing technology made books cheaper and more widely available.

By the late nineteenth century Industrial Schools had been established to better train the working classes in the numerous trades now operating in mass factories. The textile industry was one of those trades in which women and young girls were often recruited. The publication and wide circulation of “sewing primers” were seen as a way to encourage sewing skills in young girls. They included lessons and songs set to popular tunes, as well as other rules and suggestions “which will be of use in later life.”

In the introduction to this sewing primer, Louise J. Kirkwood argues, “If girls of but one grade — say from nine to twelve years — could be afforded the opportunity of becoming familiar with the use of the needle, it would be a telling step in the right direction, putting them in possession of a most valuable art, which would prove an armour of defense against temptation to idleness, which leads to want and so often crime. That this little book may give an impulse in the direction of this industrial pursuit is the desire of a practical worker.”

University of Utah rare books copy is from the John R. Park Library Collection.

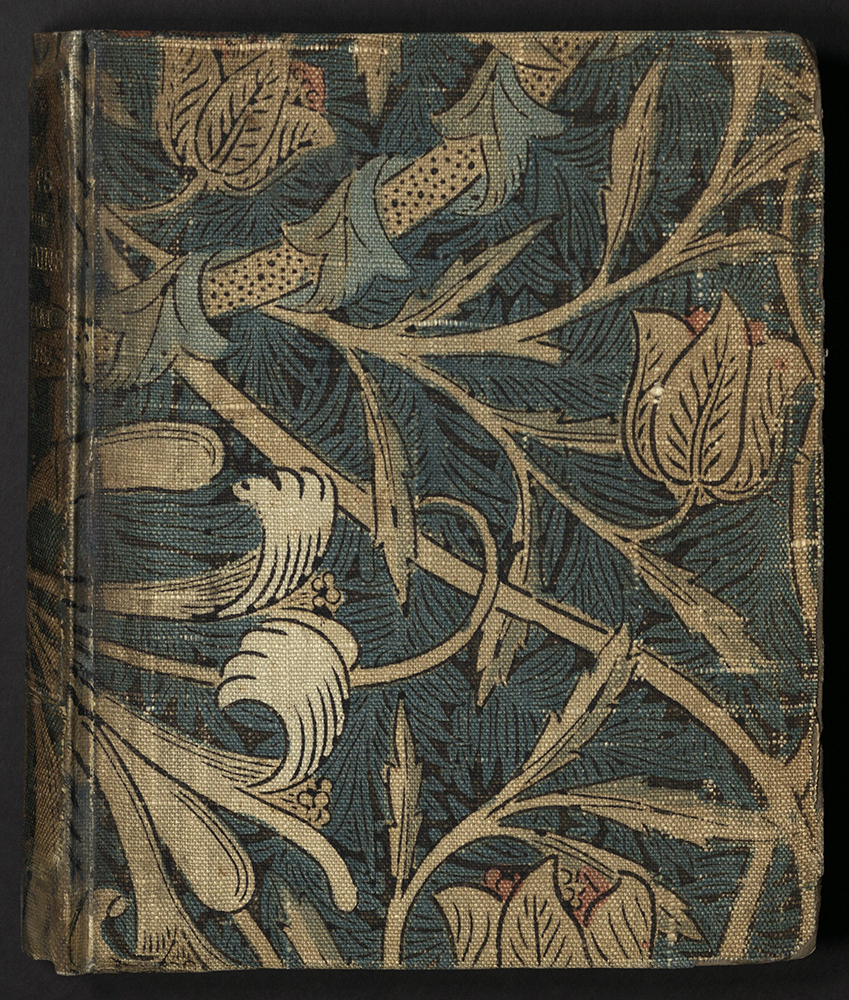

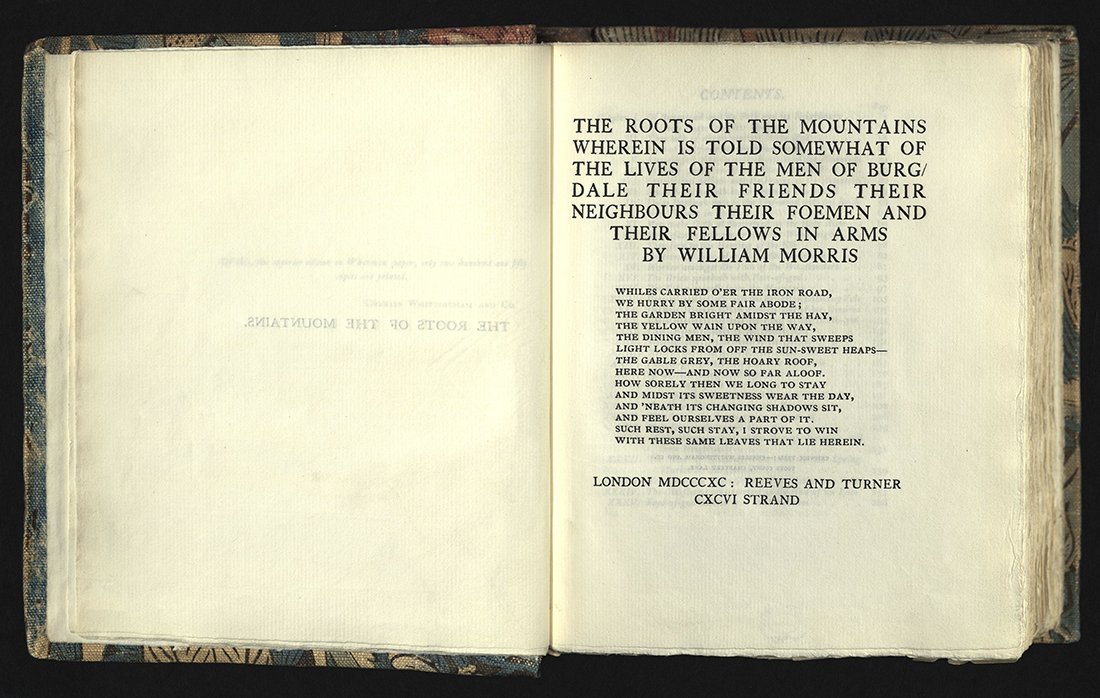

THE ROOTS OF THE MOUNTAINS

William Morris (1834-1896)

London: Reeves and Turner, 1890

PR5079 R65

Poet, designer, craftsman, and pioneer socialist William Morris led the nineteenth-century revival of the art and craft of making books. In 1891, at a time when cheap machine production dominated, Morris rented a cottage near Kelmscott House and set up three printing presses. Influenced by medieval illuminated manuscripts and the work of early printers, he designed and produced over fifty editions of works written by himself, Samuel Coleridge, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Alfred Tennyson, and others. Morris designed his own typefaces, had his own paper especially handmade using fifteenth century standards, and printed his books by hand. He returned to the woodcut for his illustrations. The books were beautiful. They were designed to be read slowly, to be treasured just as medieval manuscripts were.

Much of the impact of Morris’ books derives from the tactile sensation of superbly crafted paper and exceptionally black ink. Morris argued that it was the architecture of the printed page — word spacing, leading, and margin proportions – that made a book visually attractive. The best of designers that followed him understood his tenets of consistency and honesty and went on to revitalize the quality of book making both in limited editions and mass productions. Today, Morris is possibly best-known for his wallpaper and woven textile designs.

Binding fabric design by William Morris for Morris and Company, London. Unbleached linen upholstery fabric with hand-printed floral pattern in tan, white, crimson, pale blue and slate blue; front and rear covers without decoration; spine with gilt-stamped titling; buff endpapers; edges untrimmed. Printed by Chiswick Press, Charles Whittingham and Co., London on Whatman paper. Edition of two hundred and fifty copies.

TEXTILE DESIGN BOOK

Huddersfield [U.K.]: J. Broadbent & Co., [between 1900 and 1999]

TT715 T49 1900z

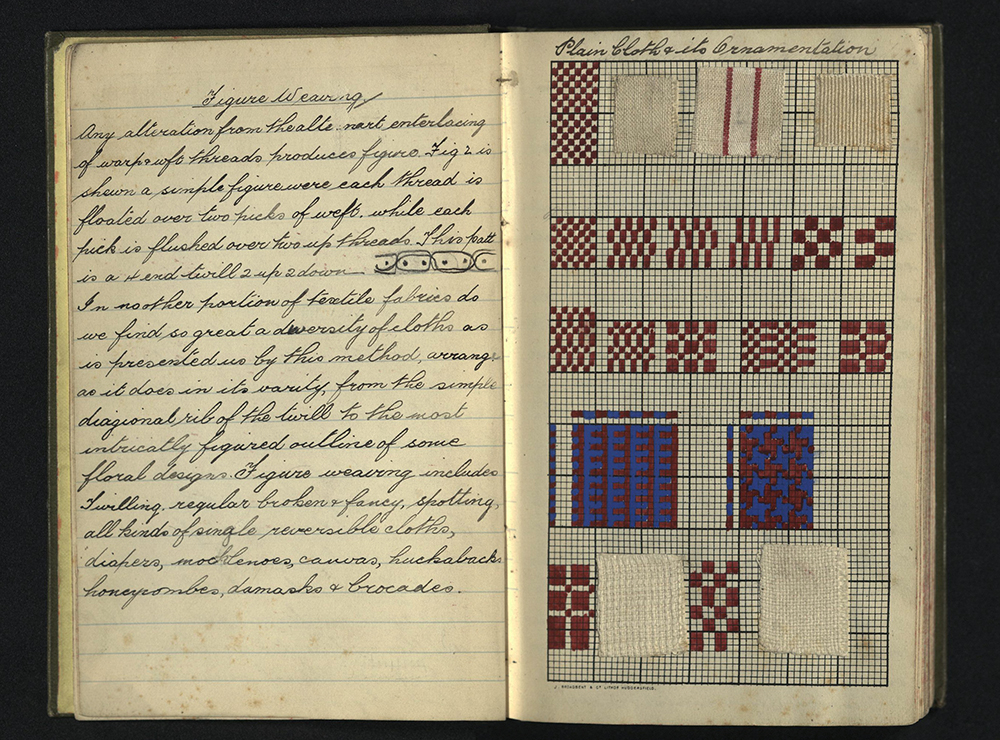

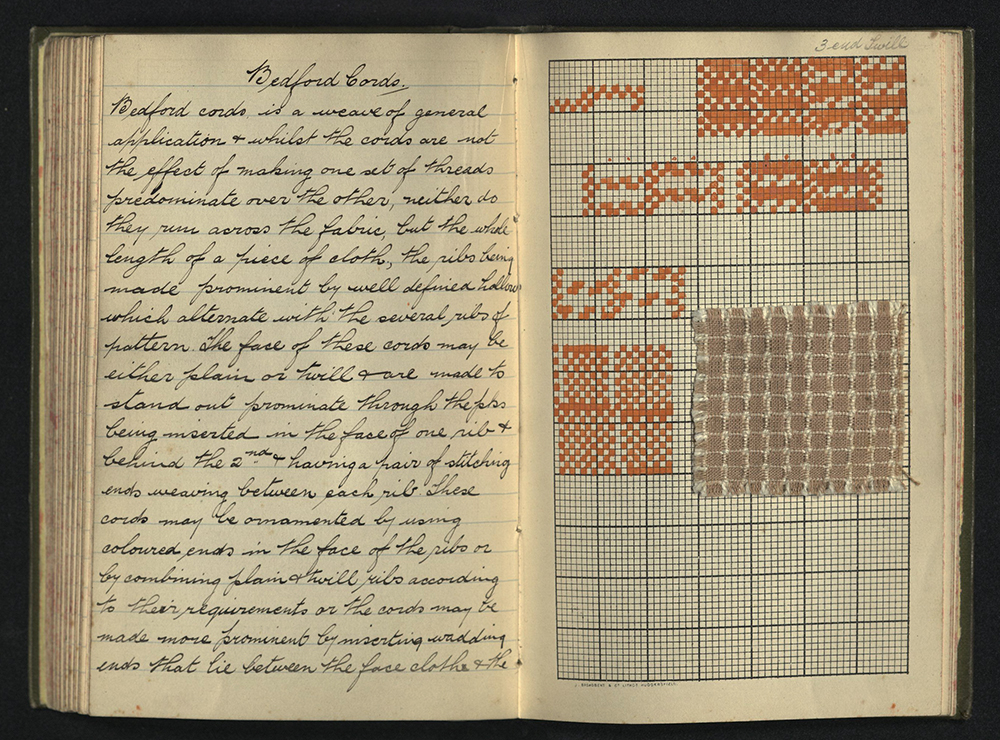

This personal textile design book was produced and sold by the J. Broadbent & Company printers. It contains ninety-six leaves of design paper, and is interleaved with ruled paper that can be used for notes. This particular design book is printed in what is called a “C pattern,” meaning the configuration of 8x8 squares. With this textile design book, we might envision a book of translations — the language of text and textile displayed on opposing pages.

On the right page, the language of textile, coded in eighty-four squares, with each square containing a grid. It is the ancient language of weaving, a technology considered by some to come from the Neolithic, if not Paleolithic, period. And on the left, the English translation, hand-written in black ink.

While there are many variations of weaving, the foundational aspect involves interlacement. That is, one set of yarns crossing over and under another set of yarns. At its most basic structure, there are two sets of yarns: one that runs along the entire stretch of the fabric, called the warp, and one that crosses back and forth as it interlaces, called the weft.

The illustrative diagram we see on the right page is a notational system called a draft and it represents the fabric. Draft notations were created and consulted by the weaver in order to better plan the work on the loom. Note the inherently binary nature of the diagram.

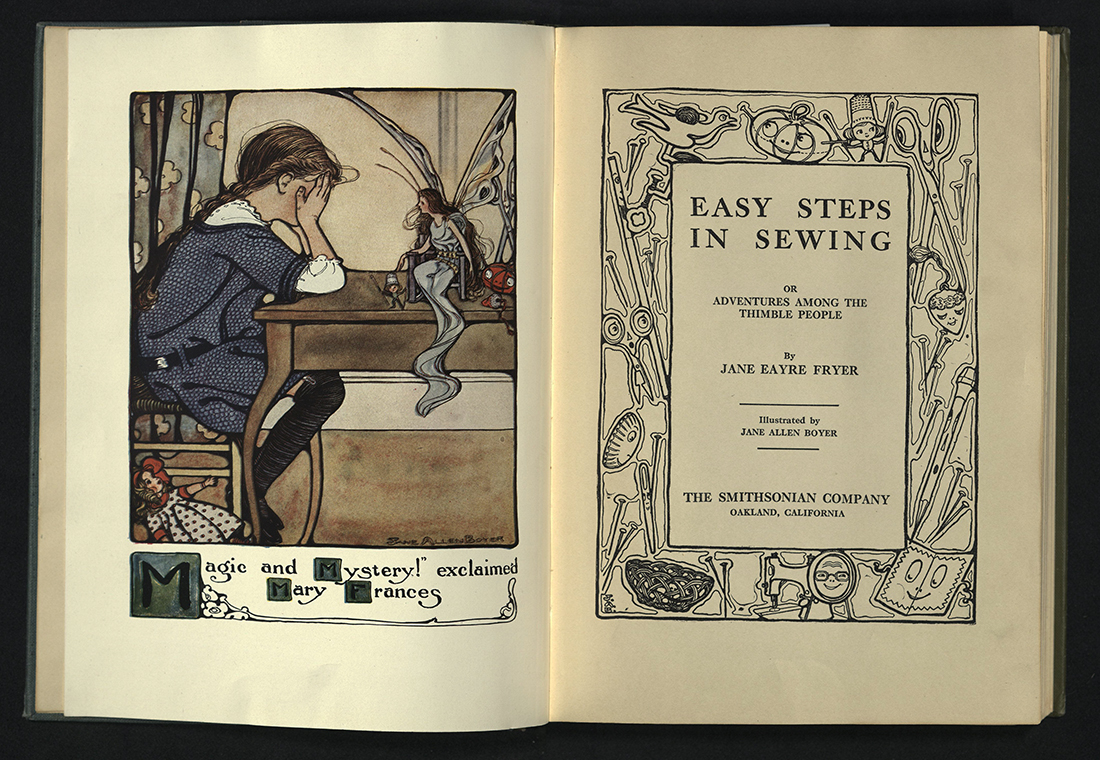

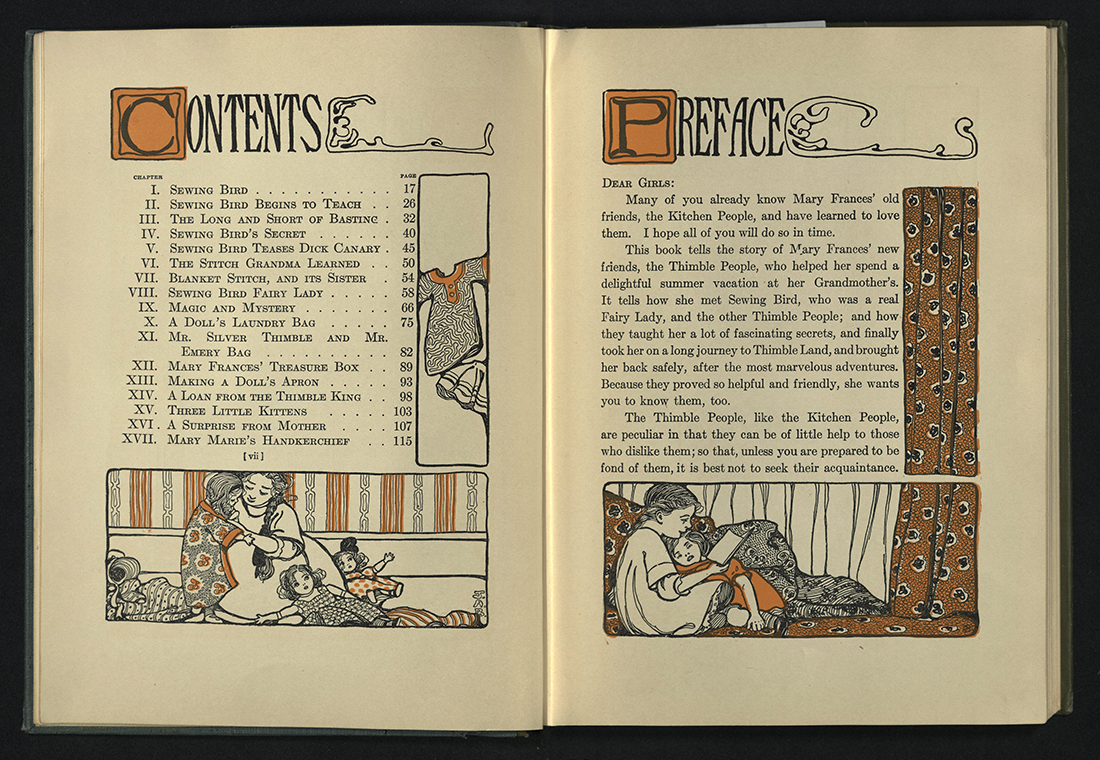

EASY STEPS IN SEWING; OR, ADVENTURES AMONG THE THIMBLE PEOPLE

Jane Eayre Fryer

Oakland, CA: The Smithsonian Company, [1928]

TT712 F7 1928a

The language of textiles was also translated and adapted for some of the youngest readers in the form of storybooks. In 1912, 36-year-old school teacher, Jane Eayre Fryer, published the first in a series of juvenile books designed to teach young girls fundamental domestic skills, combining fact and fancy for a complete course in Home-Economics. Like the sewing primers previously presented, Fryer wanted to teach useful things in an entertaining way, but unlike the primers, Fryer did so through while weaving a narrative about a young girl named Mary Frances.

But these were not mere storybooks, they were instruction books that followed the young Mary Frances as she learned domestic skills with the guidance of her fairy helpers, along with other characters such as the Kitchen People and the Thimble People. And as Mary learned the skills, so did the young readers of Fryer’s books.

In addition to Easy Steps in Sewing, Fryer also published six other volumes including: The Mary Frances Cook Book (1912); The Mary Frances Housekeeper (1914); The Mary Frances Garden Book (1915); The Mary Frances First Aid Book (1916); and The Mary Frances Knitting and Crocheting Book (1918).

TAILLEURS LENITIS

Paris: Tailleurs Lenitis, 1939

TT555 T35 1939

Prior to the 1830s, the word “tweed” was only ever used as a proper noun, referring to the Tweed river that flows through the Scottish Borders region. In the nineteenth century, the river became well known throughout the United Kingdom, and to an extent, Europe, due to its association with the famous writer, Sir Walter Scott. But the popularity of “tweed,” as we know it, is undoubtedly attributed to its life as a textile. The family of textiles that later became known as tweeds were initially sourced by merchants from Scottish Border regions. Though it might be assumed that the name was directly inspired by the local river, the term tweed likely derived from the Scottish words tweel or tweelds — a term that was used to denote any cloth in the twill weave, but most often applied to woolen fabrics.

For many decades, tweed remained a rugged textile worn by men participating in outdoor activities. However, after the First World War, shifting developments in economy, politics and the social climate provided an opportunity for tweeds to be incorporated into the women’s fashion market. Sportswear chic became the look of the inter-war era: clothing that not only expressed comfort, but also the possibility of action. These changing conceptions of femininity greatly impacted the design, production, and sale of tweeds to women in Europe and abroad. Among the French couturiers, notable designers such as Coco Chanel, played a crucial role in popularizing the tweed suit internationally. Following fishing trips with her then lover, the Duke of Westminster, Chanel began to introduce tweeds and other knitted Fair Isle designs into her fashion collections. The simplicity of men’s sporting apparel inspired Chanel’s garconne look. She wanted women to have the same level of comfort, function, and durability and decided to open a boutique in London where she sold tweed cardigan suits. Appealing to the contemporary woman, the versatile clothes of Chanel’s early collections became hugely popular and were copied across the globe.

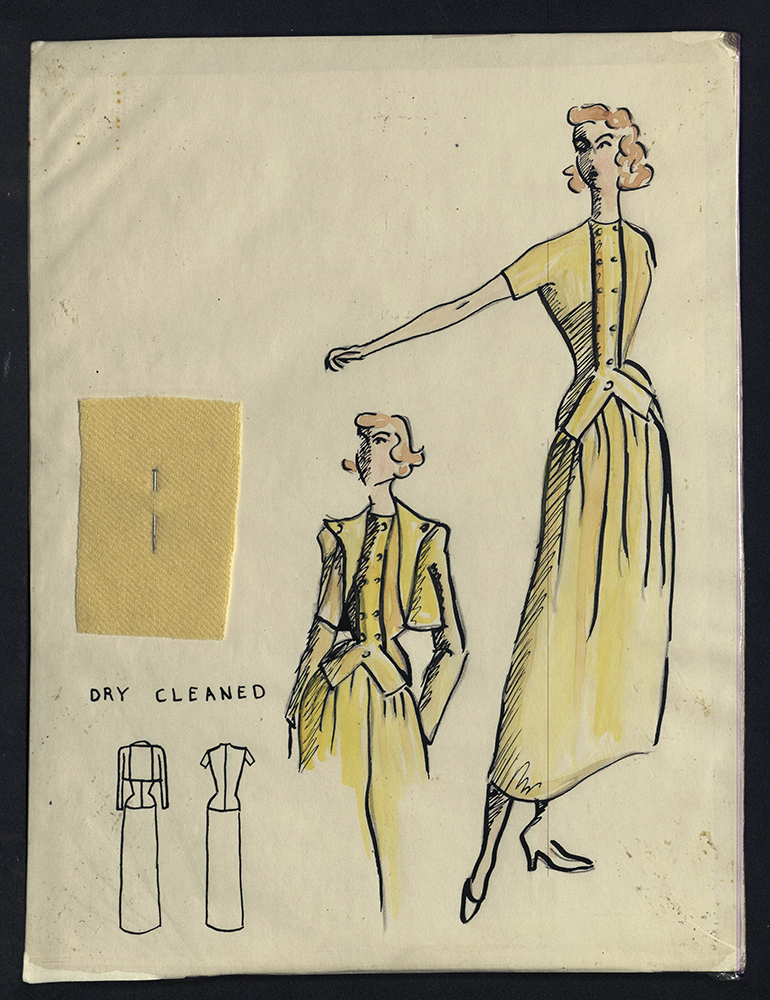

The popularity of the women’s tweed suit skyrocketed in the 1930s. “Sportswear” was no longer worn specifically for sporting activities, but could now be worn during luncheon parties in the country, or even shopping expeditions in the city. As in the words of one designer, “The clothes that sold best were those that were good for town and country.” The tweed suit was symbolic not only of an increased informality, but also of the social democratization of women’s fashion. As the thirties moved forward and Europe found itself on the brink of war once again, many of the couturiers shut their doors — some temporarily, and others for good. Despite all this, the tailored suit remained an ideal wartime outfit, due to its adaptability to different social contexts within the increasingly straitened times.

This sample catalog was created by Tailleurs Lénitis in Paris, 1939. The catalog includes forty-eight mounted samples of fabric, including wool, silk, and wool rayon blends. Each page features a large fashion illustration, at times accented in silver and adorned with colored borders and geometrical designs. Many of the illustrations feature the shoulder pads and tailored jackets of Elsa Schiaparelli’s distinctive designs, while the tailored skirts are reminiscent of Coco Chanel’s iconic two-piece women’s suit. Following the Second World War and its immediate aftermath, the tweed suit continued to have an ever more integral role in women’s wardrobes, primarily because of its adaptability and suitability for all day wear. Over the course of the next sixty years, the suit found its way into the wardrobes of style icons such as Jackie Kennedy, Princess Diana, and Brigitte Bardot. During the twentieth century, the tweed suit became more than a symbol of fashion, but a representation of the liberated woman.

FASHION DESIGN DRAWINGS

Richard-Gabriel Rummonds (b. 1931)

Twentieth century

TT506 R85 1950

Fashion and costume design drawings done by printer, Richard-Gabriel Rummonds. Box 1 includes his drawings from high school and box 2 his post-high school drawings.

Raised in California, Rummonds moved to New York to attend the School of Fine Arts at Syracuse University in 1949–1950. He later returned to California, with the intention of majoring in set and costume design and the University of California at Berkeley, but decided to major in English and Creative Writing instead. During this period he was on the staff of Occident, the student literary magazine, of which he became the editor for the Spring 1954 issue.

Rummonds began his own imprint, Plain Wrapper Press in 1966. His first book — a selection of his own poems — was printed in Quito, Ecuador. The following year, he printed a book of his short stories from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Between 1977 and 1996, Rummonds taught in the Graduate School of Library Service at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. He was the founding director of the MFA in the Book Arts Program. Subsequently, he offered workshops on printing on iron handpresses throughout the world as well as giving numerous lectures on fine printing.

HANDCRAFTED DOLLS IN VILLAGE DRESS

Jericho, Jordan: World Y.W.C.A Centre, Aqbat Jaber Refugee Camp

Twentieth century

This set of handcrafted dolls was made by women in the Aqabat Jaber Refugee Camp. The camp was established in 1948, three kilometers southwest of Jericho. Before the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, the number of registered refugees was 30,000, making Aqbat Jaber the largest camp in the West Bank. The original inhabitants came from nearly three hundred villages north of Haifa, as well as the Gaza and Hebron areas. Many of the refugees fled to Jordan during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war.

During the early 1970s, Tania Tamari Nasir began volunteering as an aid for refugee women in a Y.W.C.A located in the region. Nasir held a bachelor's degree in English Literature as well as a Fine Arts degree from Beirut College for Women (now called Lebanese-American University). Using her background in literature and art, Nasir was inspired to teach the refugee women craft and embroidery to help them make a living. With her guidance, they made embroidered goods, costuems of their country, and Nativity sets to sell the public. Nasir's experience was later published in a memoir titled My Silk Road. She is also the author of Spring is Here: Embroidered Flowers of the Palestinian Spring (2003); co-author of Palestinian Embroidery: Fallahi Cross-Stitch (1990); and has also translated the work of several prominent Arab writers.

The set includes the following figurines: “Bedouin Man” (black robe, white headdress); “Salt Woman” (black dress, basket); “Emaus Refugees” (woman with two children); “Jericho Woman” (blue dress, stick bundle on head); “Sheikh Darwish” (black robe, white tunic, headdress of green wool); “Bethlehem Woman” (black velvet dress with embroidered panels); “Jerusalem Woman” (purple dress with embroidery, basket); and “Hebronite Sheepherder” (pink and beige tunic, wool vest, gun).

Gift of Wilma Marcus from the estate of Mayor Louis Marcus, May 1984

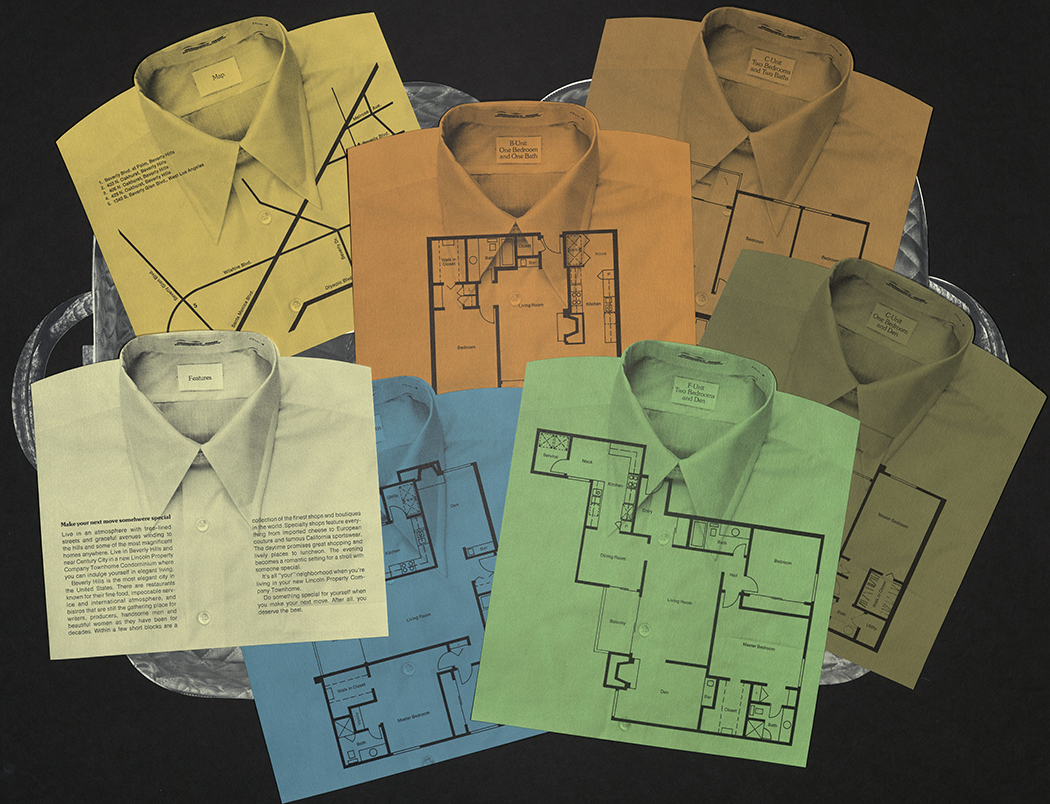

PAPER SAMPLES

Simpson Lee Paper Company

San Francisco, CA: Simpson Lee Paper Co., 1970s

TS1220 S54 1970z

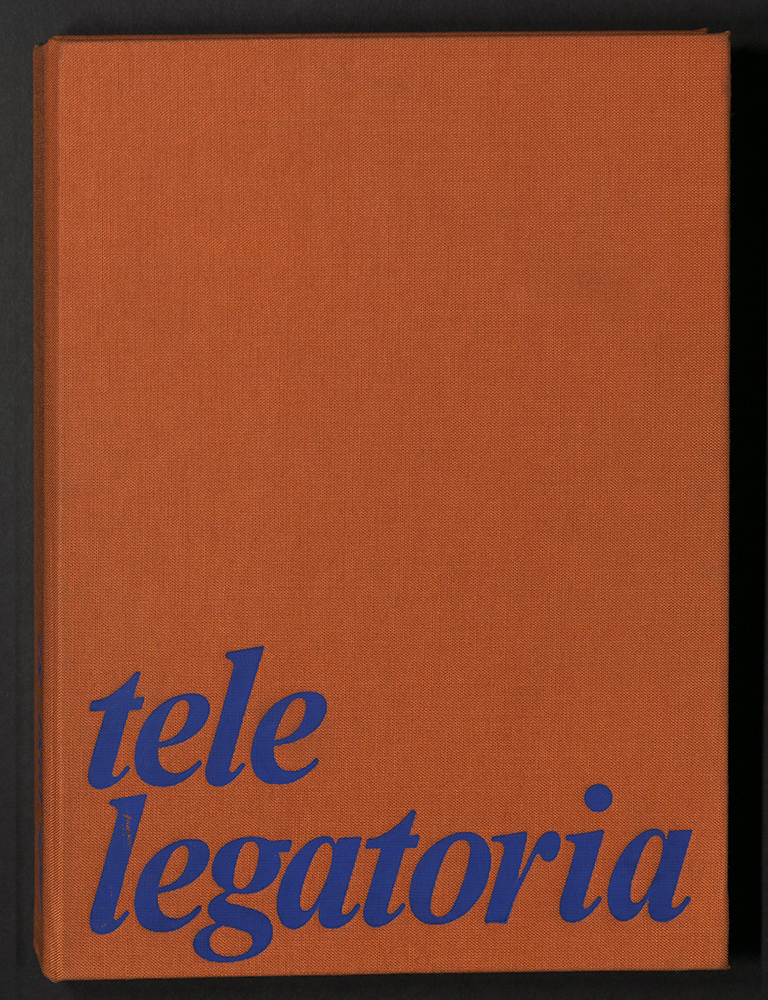

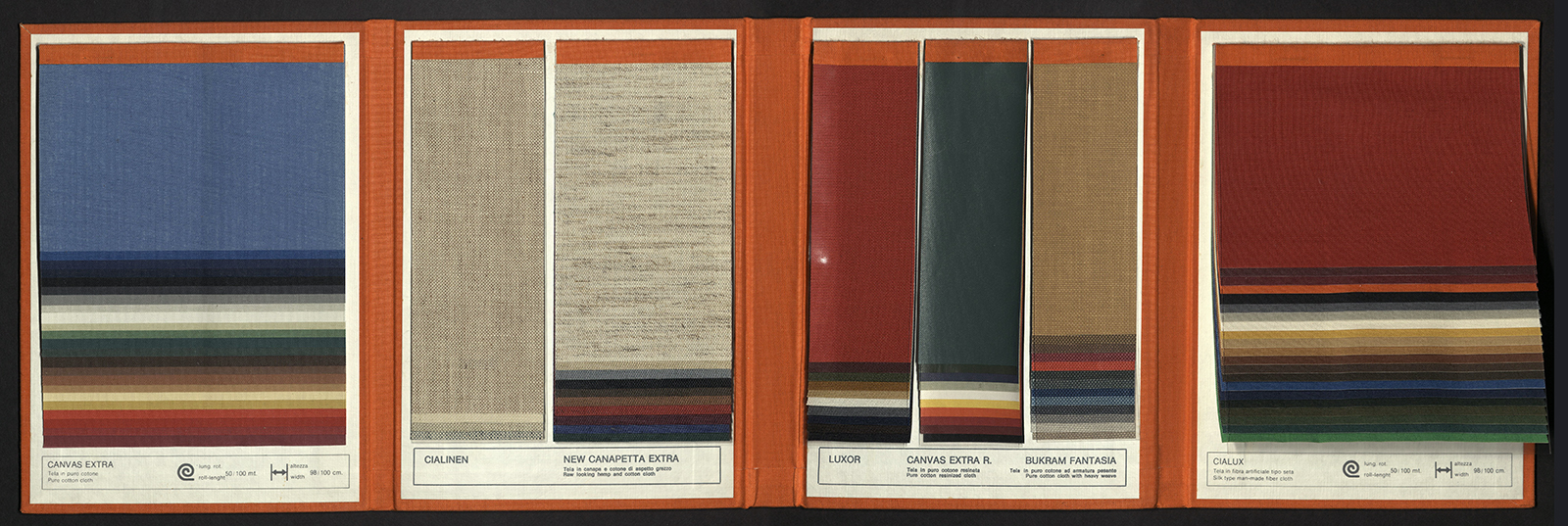

TELE LEGATORIA: TOILES POUR RELIURE (BOOKBINDING CLOTHS)

Manifattura del Seveso

Cusano, Milanino, Italy: Manifattura del Seveso, 1981

Z274 M35 1981

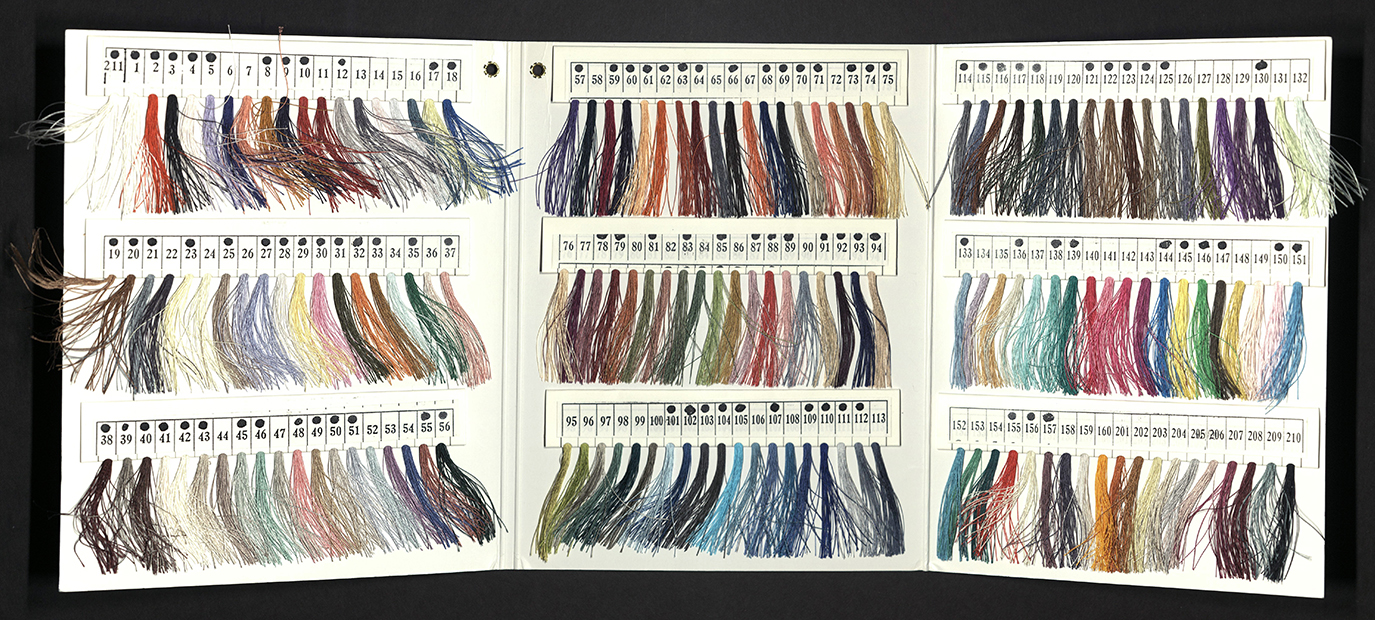

TIRE BRAND SILK THREAD: COLOR SAMPLES

Fujii Sen-I Co. Ltd.

Kirkland, WA: Fujii Sen-I Co. Ltd, 1990s

HD9929 T3 F8 1990z

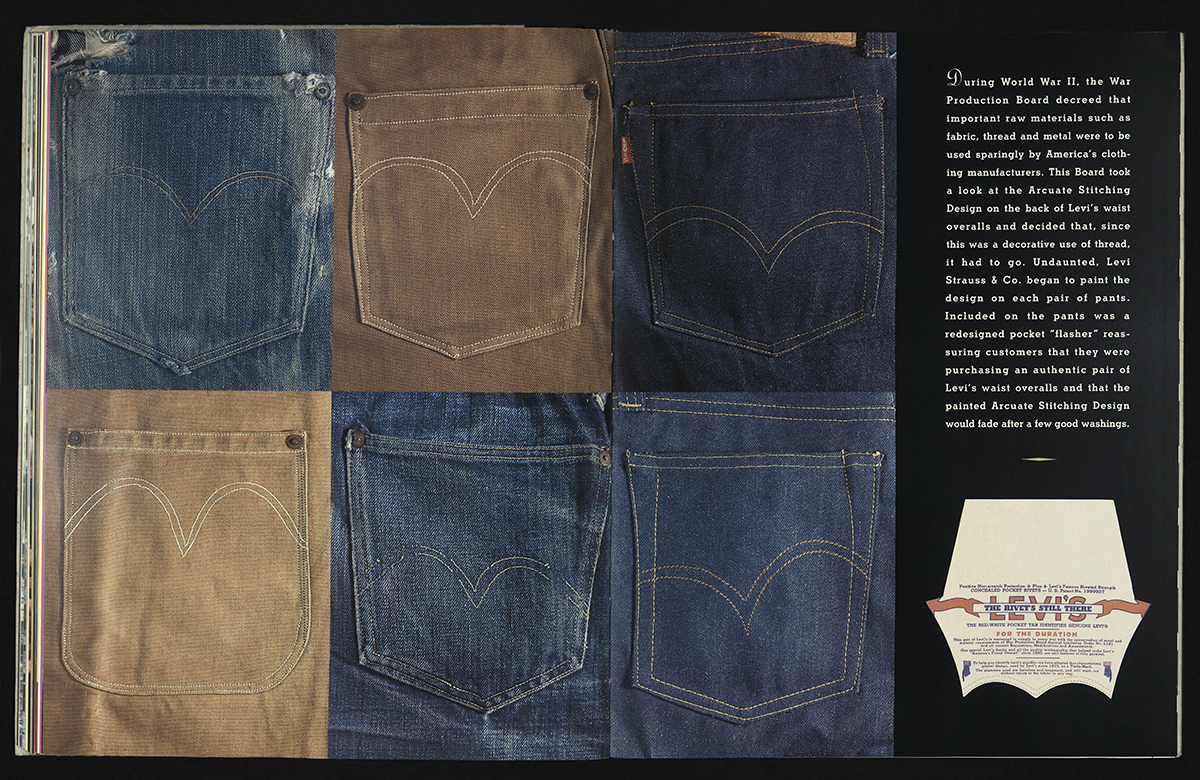

501: THIS IS A PAIR OF LEVI’S JEANS

Lynn Downey

San Francisco, CA: Levi Strauss & Co. Publishers, 1995

HD9940 U6 L454 1995

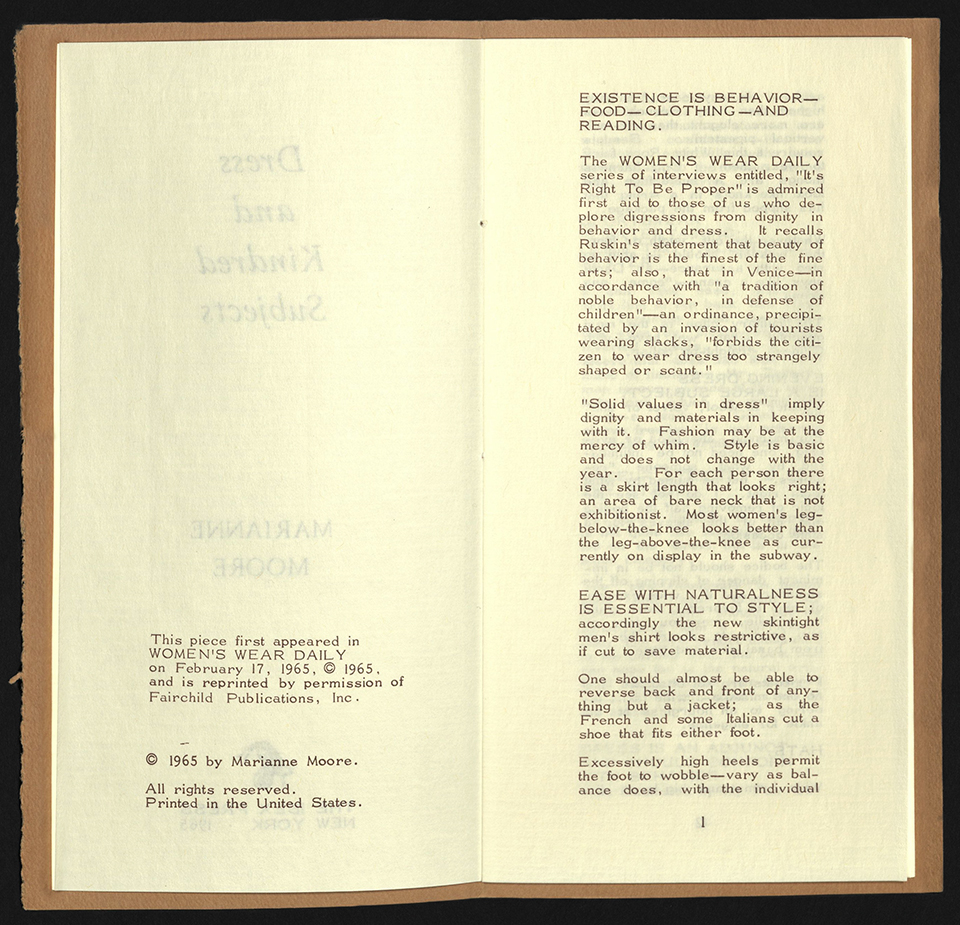

DRESS AND KINDRED SPIRITS

Marianne Moore (1887-1972)

New York, NY: Ibex Press, 1965

PS3525 O5616 D7 1965

Women’s Wear Daily was founded as an extension of the menswear journal Daily News Record in 1910. Founded by Edmund Fairchild, the fashion-forward publication quickly acquired notoriety among the New York clothing industry and was referred to as the “Bible of Fashion.” The trade journal provided information on changing trends and breaking news in the fashion, beauty, and retail industries to a demographic of readers consisting largely of retailers, designers, manufacturers, marketers, financiers, media executives, advertising agencies, socialites and trend makers. By the mid-century, Women’s Wear Daily turned its focus on the “human side of fashion” and began reporting on the social scene, meanwhile manufacturing a cult of celebrity around fashion designers.

Demonstrating her own interest in fashion, American poet Marianne Moore contributed an essay to the February 1965 issue of Women’s Wear Daily titled “Dress and Kindred Subjects.” The essay was reprinted by the Ibex Press in an edition of 100 copies. Cover drawing done by Laurence Scott. University of Utah copy is numbered ‘R’.

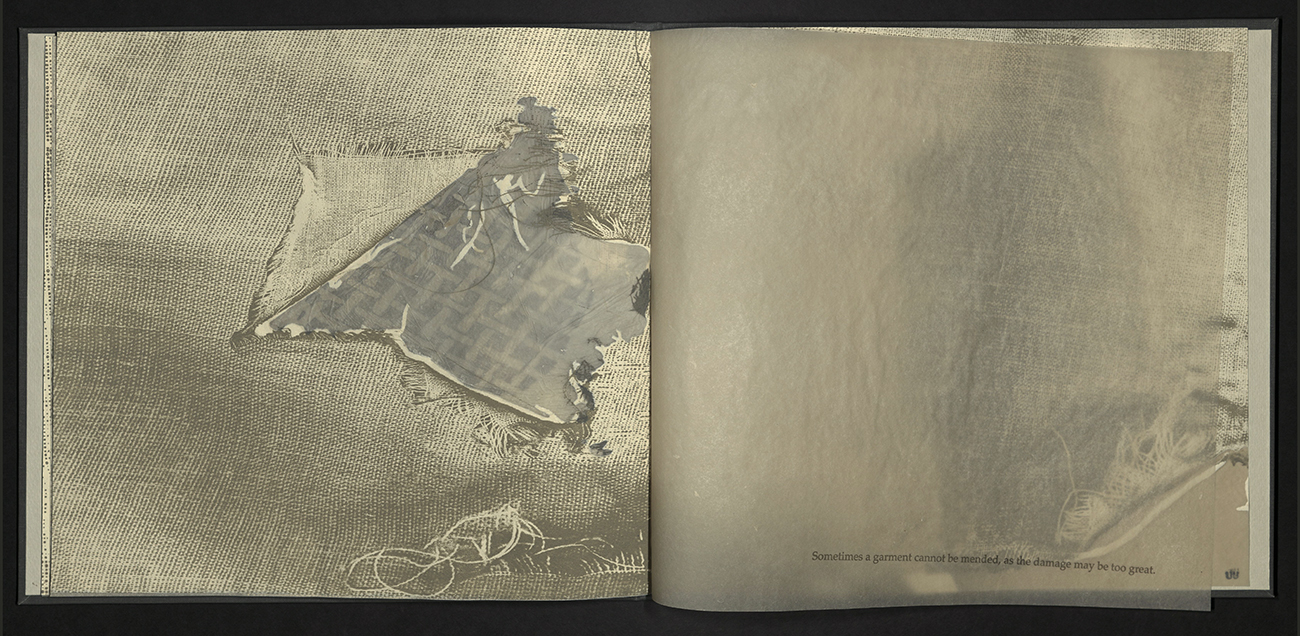

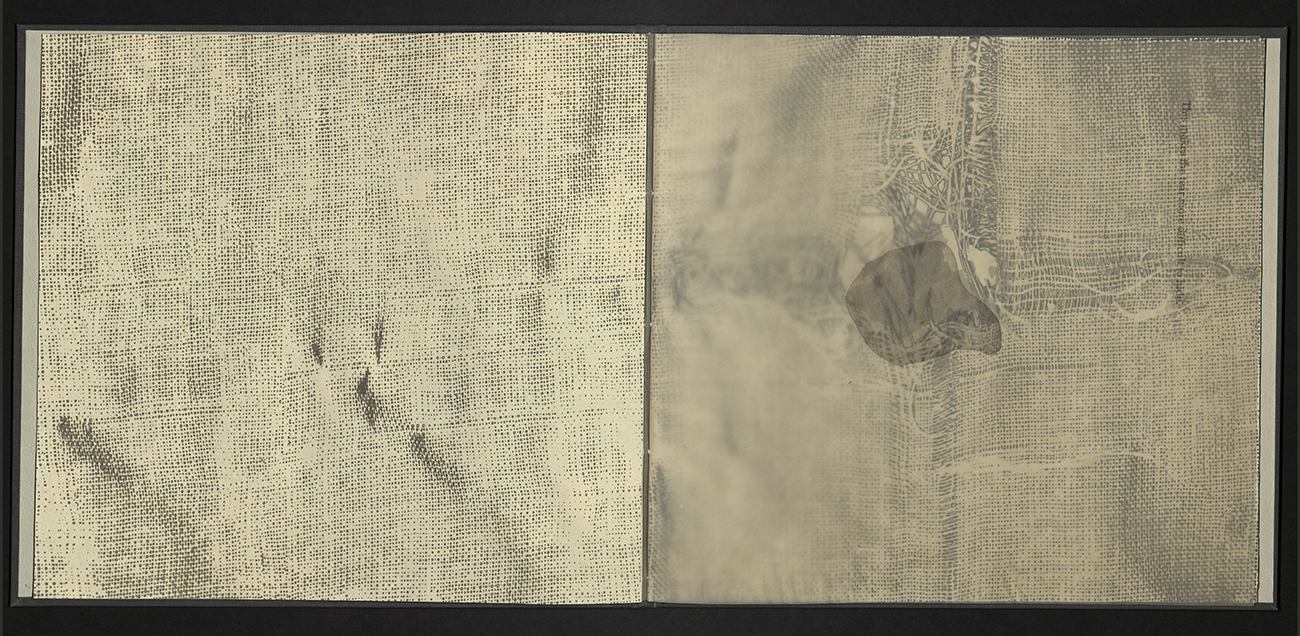

THE WARDROBE

Teresa Pankartz

Chicago, IL: Artists Book Works, 1988

N7433.4 P26 W27 1988

While we may no longer perpetuate the stereotypes of domestic work being solely women’s work, there is still an undeniable connection between textiles, female writing, and the shared experience of women. During the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s, second-wave feminists gained new interest in family textiles, collecting quilts and samplers, and trying to learn traditional textile arts. In searching for missing records and hidden histories, they saw in textiles a unique form of female writing that implicitly chronicled the lives and labors of their mothers and grandmothers before them.

Teresa Pankratz dedicates her book, The Wardrobe, to her mother “whose closets bulge with story.” Designed to resemble a wardrobe of clothes, interlaced with illustrations and text. Pankratz muses on the differences and similarities between her mothers wardrobe and her own, with each page highlighting an article of clothing that is intrinsically linked to a specific memory or event. Text and illustrations folded accordion style in a mahogany box designed to resemble a wardrobe. Edition of five copies. University of Utah rare books copy is no. 3.

LOOM

Carol June Barton

Bethesda, MD: Carol June Barton, 1989

N7433.4 B376 L66 1989

Carol Barton is a book artist, paper engineer, curator, and educator. She is the proprietor of Popular Kinetics Press and has published several editions of artist books. She may be best known for her series of interactive workbooks, The Pocket Paper Engineer. Fueled by her interest in book arts, Barton embarked on a two-year study of movable and pop-up books. She traveled to libraries and collections across the United States where she discovered a wide variety of books utilizing sculptural formats and uncommon engineering techniques. As she began to better understand the materials and methods used in the construction of these books, Barton began compiling ideas for the production of her own editions of artist books.

One result of her research was that Barton is credited with reestablishing the tunnel book as a book structure. In Loom, the reader travels through a series of Persian rugs while, landscapes and space to reveal an image of the world. An anonymous quote, translated from Persian greets the reader at the end, “No one yet hath unravelled a knot from the skein of the universe. And each who came and essayed the same but made the tangle worse.”

Loom was assisted by Katherine Barrow, Linda Couvillion, Gayle Garrett, Ann Kalmbach, Judy McCarthy, Douglas Olds, Michael Sediman, Esther K Smith, and Brad Freeman of Pyramid Atlantic. With Funds from Maryland State Arts Council. Edition of six hundred copies. University of Utah rare books copy is number 562.

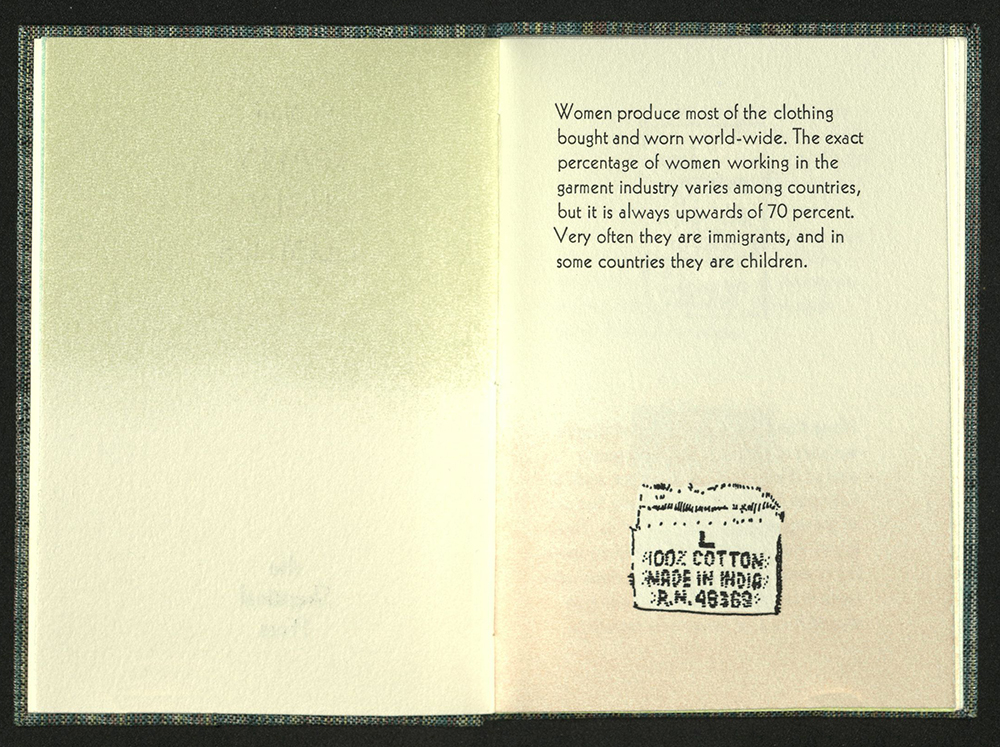

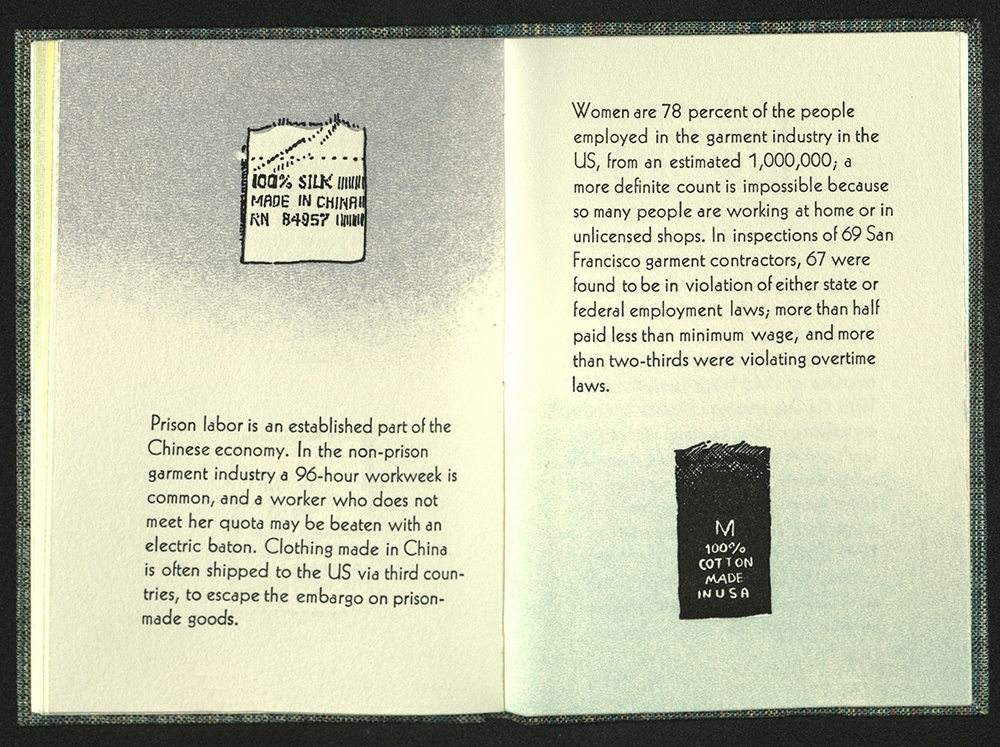

SOME REALLY UGLY CLOTHES

[New Haven, CT]: Skeptical Press, [1996]

HD2337 S64 1996

Clothing is not only a testament of our past, it is also the outwardly expression of who we are. It is a reflection of our personalities, a connection to unique cultures and communities, and sometimes even a declaration of our political beliefs. We wear our heart on our sleeves, as they say, and sometimes we wear some really ugly clothes.

From the American textile workers’ strikes of the early twentienth centuries, to the contemporary inhumane conditions of textile workers in factories here and abroad, and the major environmental impacts resulting from synthetic waste and water use — the textile industry has been and continues to be controversial.

In 1996, the Skeptical Press of New Haven, Connecticut produced this little booklet to raise awareness about the ugly facts of fashion. Accompanied by images of clothing tags, the book digs deep into the serious issues of sweatshop labor, using excerpts from articles written in major publications like The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and South China Morning Post, to name a few. The twenty—one unnumbered pages include information such as the following,

"Women produce most of the clothing bought and worn world-wide. The exact percentage of women working in the garment industry varies among countries, but it is always upwards of 70 percent. Very often they are immigrants, and in some countries they are children."

"Hong Kong is the world’s third biggest supplier of clothing, but many goods marked Made in Hong Kong are made in China or Thailand. Thai industry has one of the worst safety records in Asia. There are an estimated 40 million children working in various jobs in Thailand; those who work in factories have often been purchased from rural parents by recruiters."

While the information provided is truly ugly, the book ends on a reflective note, providing a list of all the articles of clothing the author owns: 4 pairs of jeans; 6 sweaters; 4 skirts; 3 dresses; 7 blouses; 2 jackets; 2 pairs of slacks; 16 Tshirts; 1 turtleneck; plus various socks, tights and underwear. The final statement, “Okay these are my clothes, but I don’t know what to do about it."

Printed with Kabel light type on Rives Heavyweight paper. Bound in striped cloth covers, with paper spine label. Edition of thirty-five copies. University of Utah rare books copy is no. 235.

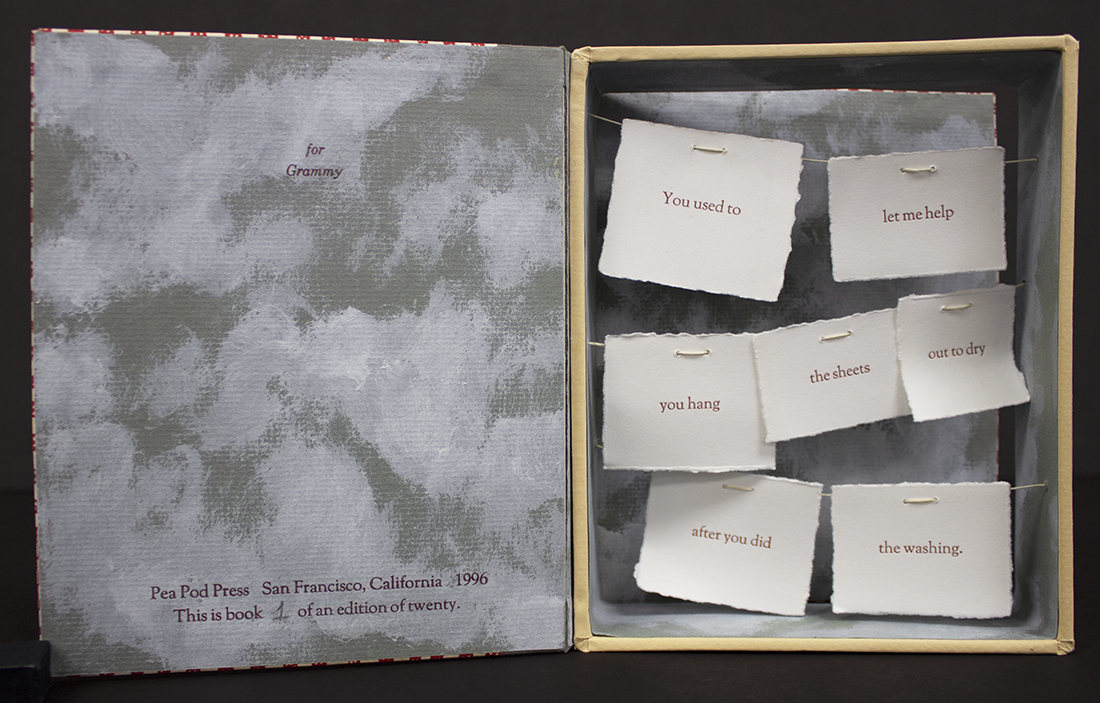

HANGING LAUNDRY

Emily Payne

San Francisco, CA: Pea Pod Press, 1996

N7433.4.P39 H35 1996

Poetry printed on torn paper suspended from string inside a box. Printing, hand painting, cover linoleum cut and book construction by Emily Payne.

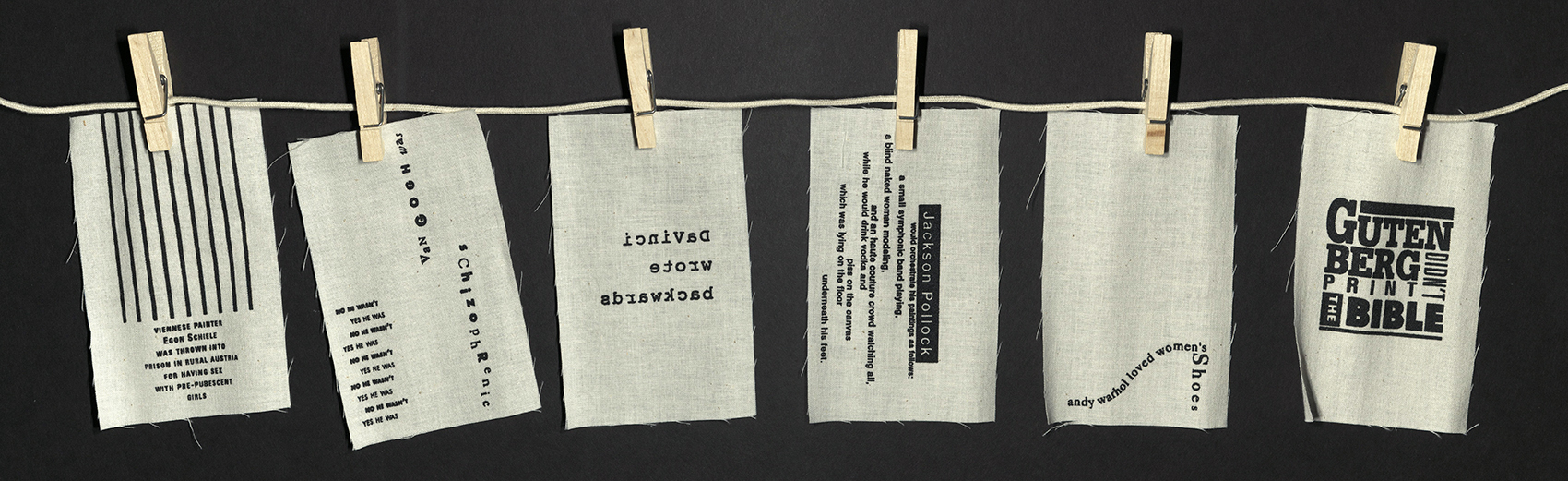

ON THE LINE

Linda Johnson and Kristy Lewis

Lafayette, IN: L. Johnson, K. Lewis, 1997

N7433.4 J66 O5 1997

On the Line is a collaborative project created by Linda Johnson and Kristy Lewis for 1997 show titled Van Gogh’s Ear and Other Art Stories. Johnson and Lewis collected stories, rumors, little known facts and folktales about well-known artists. They searched for “the kind of scoop that usually doesn’t find it’s way into history books.”

Most of these stories have been related through a message-making process known as “word of mouth” giving them a certain less than tangible quality. The collection of stories became content for an artists’ book, through which these juicy tidbits of information are passed on to others. The book was designed so that the viewer has to interact with the piece in a symbolic way of hanging out the dirty laundry. To further perpetuate this process of person-to-person rumoring, the Johnson and Lewis requested that their initial contacts pass a copy of the project to another artist, art patron, art historian, or anyone else whom they considered to be “in the know” on such gossip.

This limited-edition bookwork was supported in part with public funds from the Women’s Studio Workshop and the New York State Council on the Arts. Contributors include Robert Brinkerhoff, Harvey Kaner, Jim Walker, Jacob Livshultz, Maria Rougal, and Alexsandra Sukhoy. Printed on 100% cotton muslin in an edition of one hundred and twenty-five copies. University of Utah rare books copy is number 86.

MODERN (LAUNDRY) PRODUCTION

Susan Johanknecht

London: Gefn Press & Paupers Productions, 2001

PS3560 U26 M6 2001

The text for Modern (Laundry) Production was derived from three sources. The first two, titled Modern Laundry Production (1945) and Industrial Psychology and the Laundry Trade (1947) describe the processes and machinery which structure the operators lives. The third, an article titled “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism for the 1980s” was published in volume 15 of The Socialist Review. Susan Johanknecht’s artist’s book carries with it her interest in innovative writing practices which use existing “working” languages. The imagery is based on early twentieth—century time and motion studies, which divided up and recorded “cycles” of work with the view to standardization and increased production — a visual documentation of work, where the body and machine become linked as cyborgs. The concertina structure smoothly turns from front to back, guiding the reader into performing their own repetitive loop.

Text in 12pt Gill Sans and Gill Sans Italic, title in 18pt Gill Sans Bold Italic, printed offset litho in dark blue by Michael Taylor at Paupers Press, London. Sheets glued and accordion folded, housed in a brown card slipcase rubber stamped with the title in white ink. 150 copies co-published with Paupers Publications, London 2001.

Because we do not typically see the production of textiles, we often forget that they are, in most cases, made by human hands. The same could be said about books. Yes, books are now produced by mechanical robots by the thousands all over the world. But at one point in time, the entire process was done by hand.

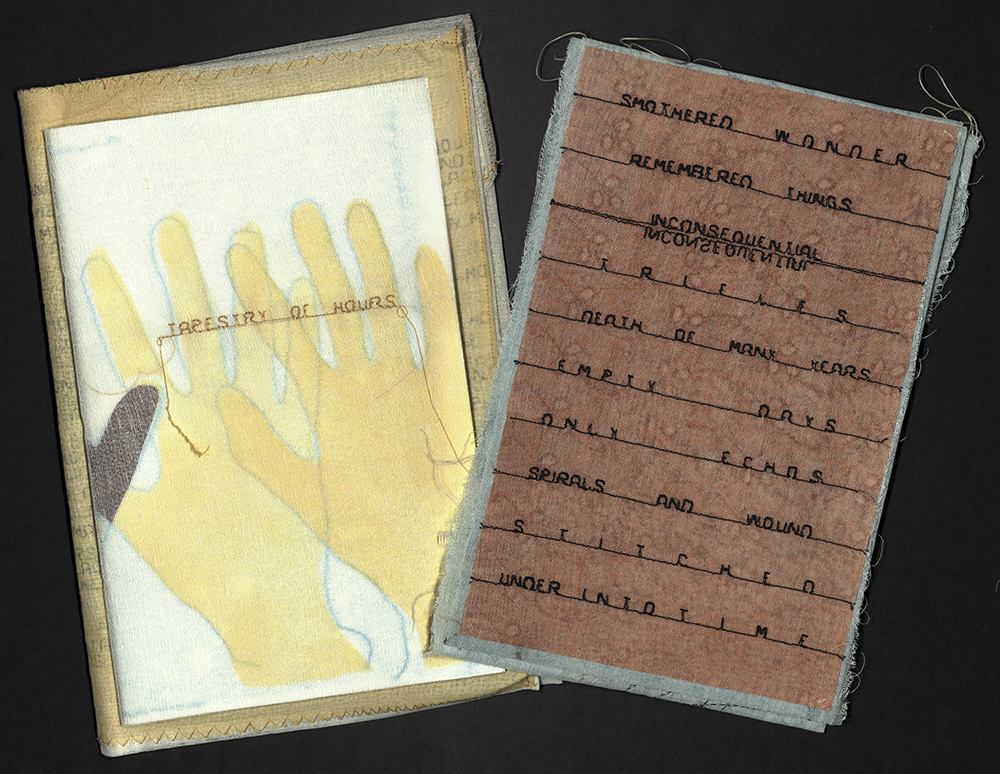

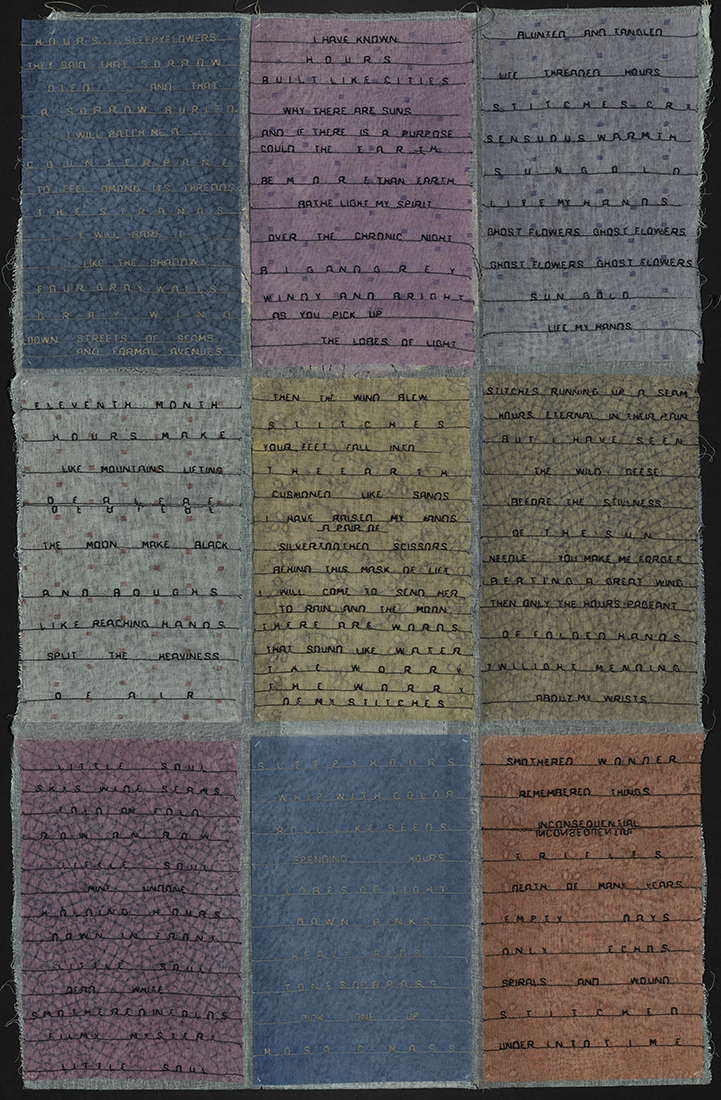

Our familiarity with the book has made us blind to the intricate details of the paper, the binding, and architectural structure. When we look at the book we only ever see the text, not the textiles. Artist Claire Van Vliet seeks to redirect our attention to those details by experimenting with the book’s form and structure in innovative ways. She is, perhaps, best known for her weaving techniques, interlocking the binding with colorful strips of paper and thread.

Claire Van Vliet is an artist, illustrator, typographer and founder of the Janus Press, named after the Roman god of beginnings and transitions — a perfect metaphor for the kinds of books she creates. For Van Vliet,

"… To read a book is an act of opening — we open it and are open to what is inside — we expect to receive from a book... All the physical components of a book can act as facilitators for the essence of the text. They can engage the senses and widen the comprehension of the text — ideally, without interfering in any way. Reading a book is a dialogue, and the more the reader is encouraged to bring to the act of reading, the better it is for the author."

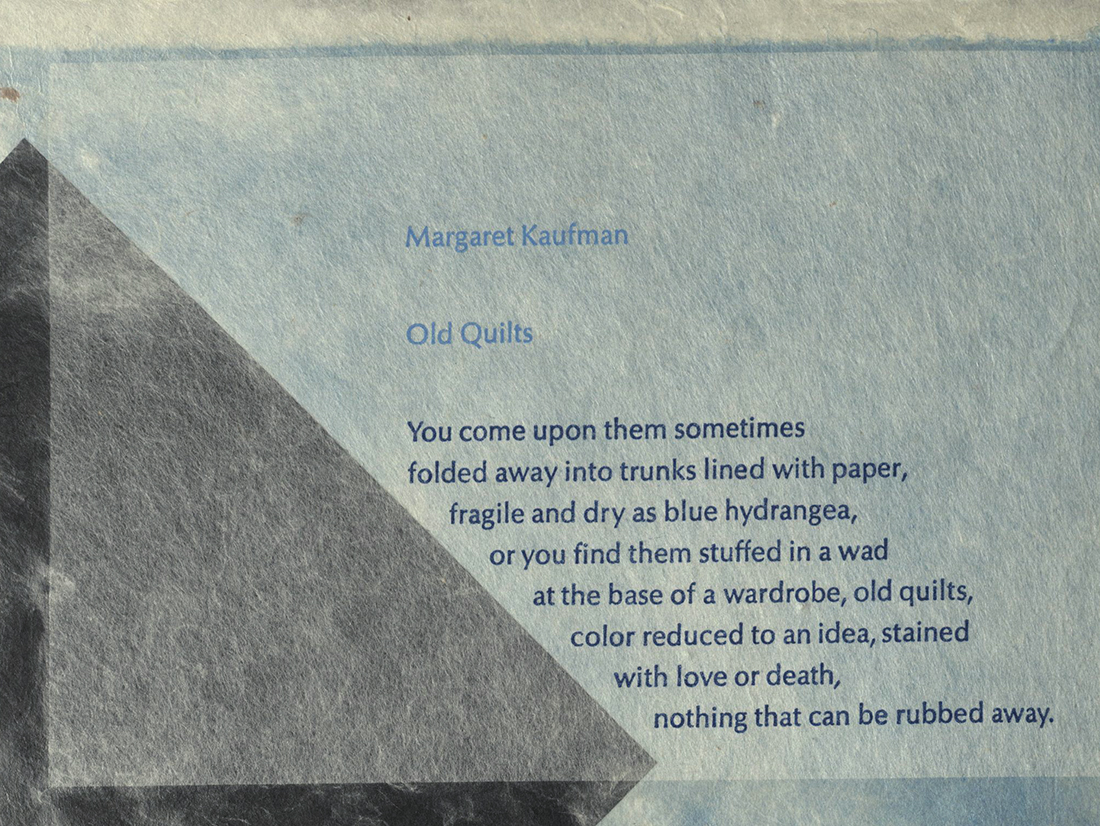

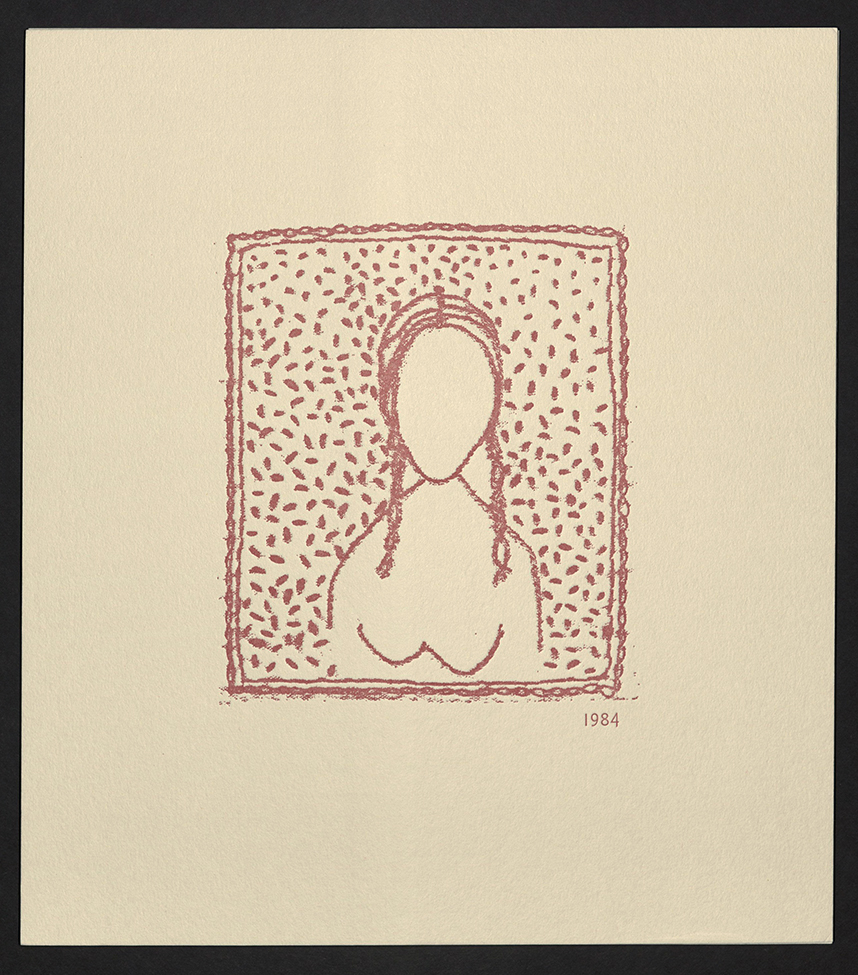

OLD QUILTS

Margaret Kaufman

Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Center for Book Arts; West Burke, VT: Janus Press, 1989

Z232.5 J36 K378 1989

Handset in 10 and 12 pt. Optima. Printed dry in three blues on Tenjugo inclusion in “quilt” of Japanese lace papers and kozo and gampi papers handmade by Amanda Degener. Set by Michael Tarachow at Pentagram Press, Minneapolis. Designed by Claire Van Vliet and made with Amanda Degener and Barb Schubring at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts and Cave Studio. Edition of one hundred and forty copies, numbered.

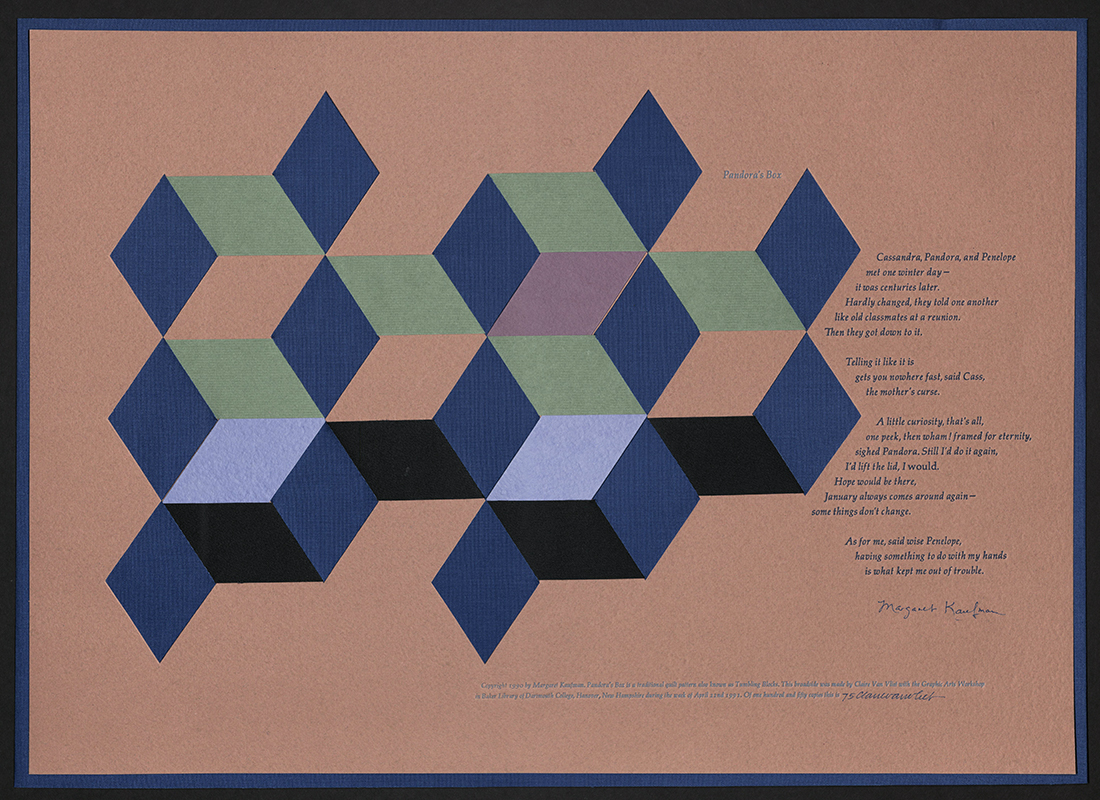

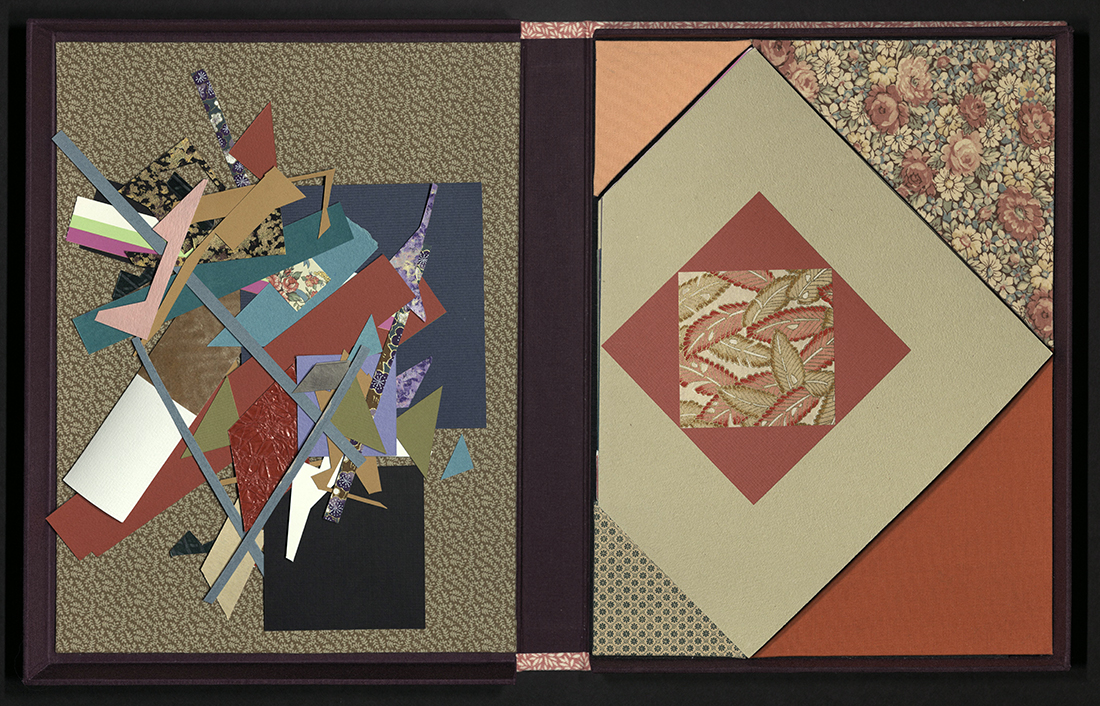

PANDORA'S BOX

Margaret Kaufman

Hanover, NH: Graphic Arts Workshop, Baker Library, Dartmouth College, 1991

Z232.5 J36 K379 1991

Handset in 18 pt Palatino italic, colophon in 10 pt. Printed damp on Barcham Green India paper. Embedded quilt pattern of tumbling blocks woven of paper and cloth. Printed with assistance from Stephanie Westnedge who completed the embedded image at Janus Press.

BEAUTY IN USE

Sandra McPherson

Newark, VT: Janus Press, 1997

Z232.5 J36 M35 1997

Thirteen poems inspired by African-American Quilts. The twenty quilt square pages are two-sided patterns constructed with interlocking and woven pieces of paper collected over a period of five years. Many of the papers were made especially for this project at the press and by different papermakers. Chiyogami, paste, marbled, and printed papers are included. The binding concertina of Twinrocker abaca is a book structure invented specifically for this project by Claire Van Vliet and, in the spirit of the interlocked quilt squares, is non-adhesive. The tray case is covered with three different cottons. Accompanied by a bag of small pieces of paper left over from the construction of the book. Edition of one hundred and fifty copies, signed by the participants.

DEEP IN THE TERRITORY

Margaret Kaufman

Newark, VT: Janus Press, 1998

Z232.5 J36 K373 1998

Deep in the Territory is the third in a series of quilt books written by poet Margaret Kaufman and created by Van Vliet and the Janus Press. The thirteen quilts, accompanied by Kaufman’s poems, are built from interlocking strips and shapes of paper to form double-sided squares, with the two sides varying radically in most instances, both in hue and in format. Most amazingly, the complex book has no binding — in that there is no thread or glue holding it together. The text and quilt papers are folded, cut and woven into tight patterns that hold all on their own.

Kaufman’s poems, including the titular “Deep in the Territory,” were inspired by plainswomen’s quilts. A collector of such quilts, Kaufman closely observes the artifact and stitches together the poem, which then combines with Van Vliet’s interplay of materials — text and textile.

Included with the book is a bag of paper scraps, which Van Vliet explained, “just seemed too nice to throw away.”

Thirteen quilts, opposite thirteen poems, are built from interlocking strips and shapes of various handmade and machine-made papers to form double-sided squares. Included is a bag of paper scraps. Letterpress printed. Binding structure and design by Claire Van Vliet. Housed in a cloth-covered clamshell box. Edition of one hundred and twenty copies. University of Utah rare books copy is signed to the Marriott Library by Claire Van Vliet and initialed by the poet.

AUNT SALLIE'S LAMENT

Margaret Kaufman

Newark, VT: Janus Press, 2004

N7433.4 V37 A8 2004

Book design by Claire Van Vliet. Each page is a different combination of colors and geometric shapes resembling quilt blocks. Issued in box. Edition of one hundred and twenty copies, signed by the poet and artist.

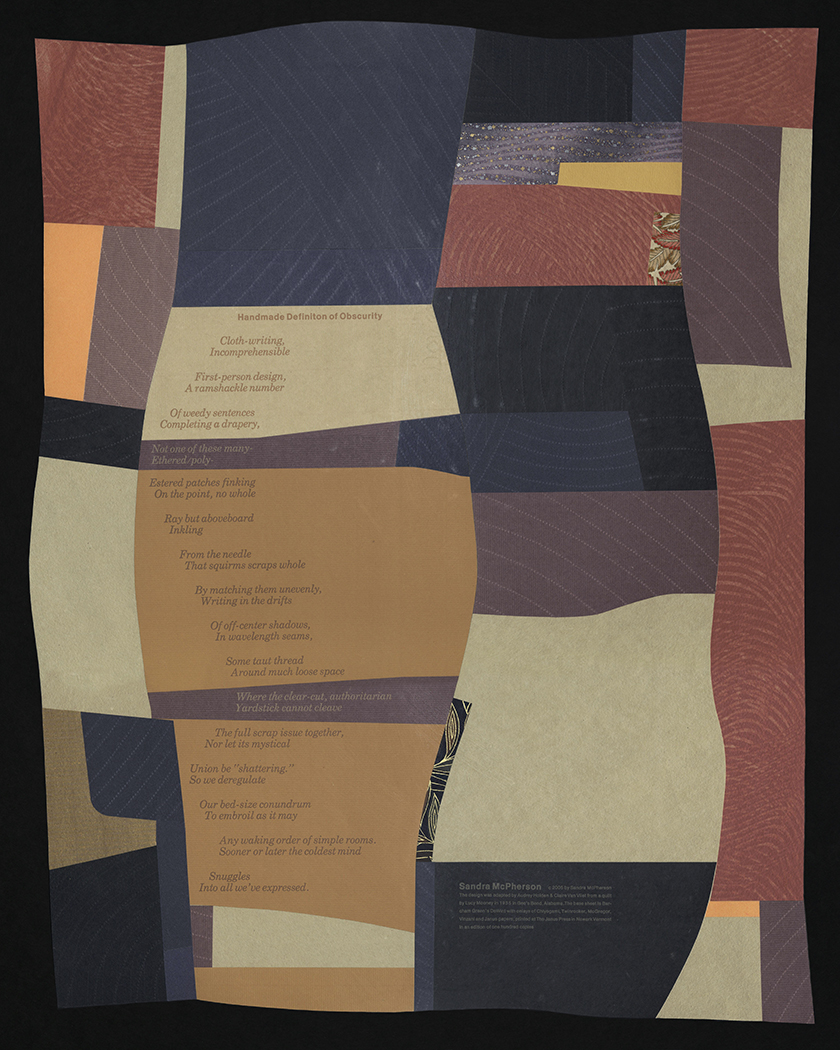

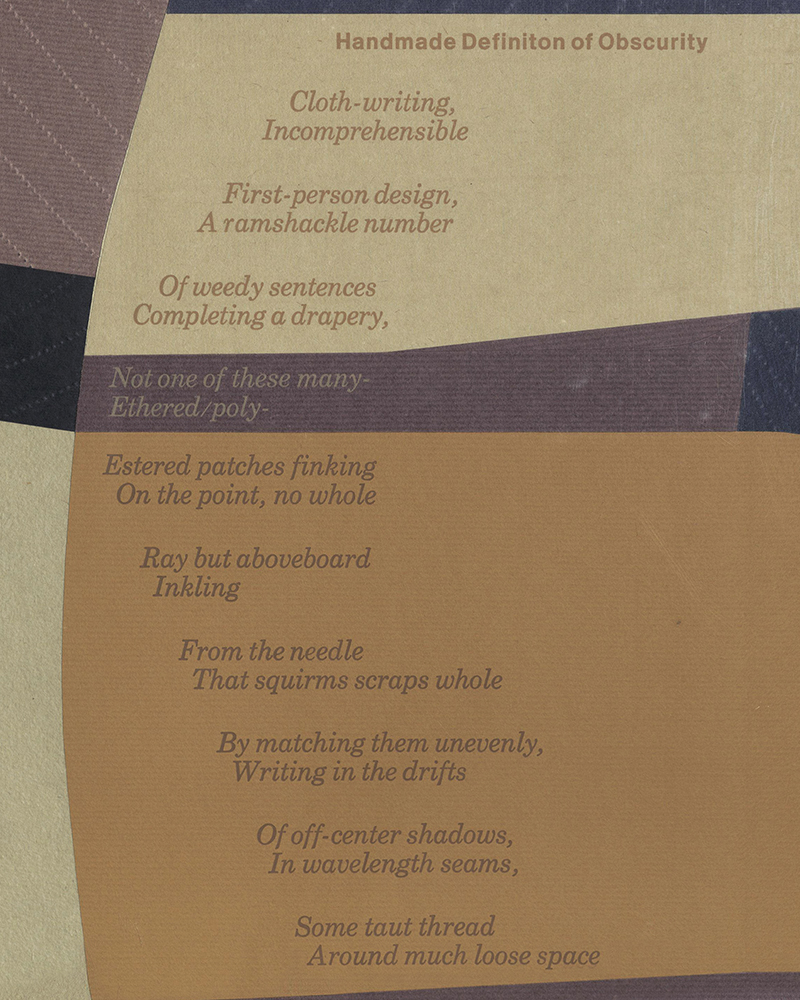

HANDMADE DEFINITION OF OBSCURITY

Sandra McPherson

Newark, VT: Janus Press, 2005

PS3563 A326 H36 2005

Broadside poem. Titles handset in 16 pt Helvetica Medium, text in 18 pt Century Schoolbook italic by Tamar Schuman, colophon in 10 pt Helvetica. Printed dry in ochres on calendered Barcham Green Dover and McGregor—Vinzini ochre and mauve papers collaged onto Barcham Green DeWint paper in an interwove design using colored, paste, and papers patterned with a tailor's roulette, including Japanese Chiyogami. Twinrocker black abaca, and Janus dark blue, black, orange, yellow. Assembled with assistance from Audrey Holden and Andrew Miller-Brown. Edition of 100 copies from Janus Press catalogue. Wonderful poem and elaborate even by Janus Press standards broadside in a quilt design.

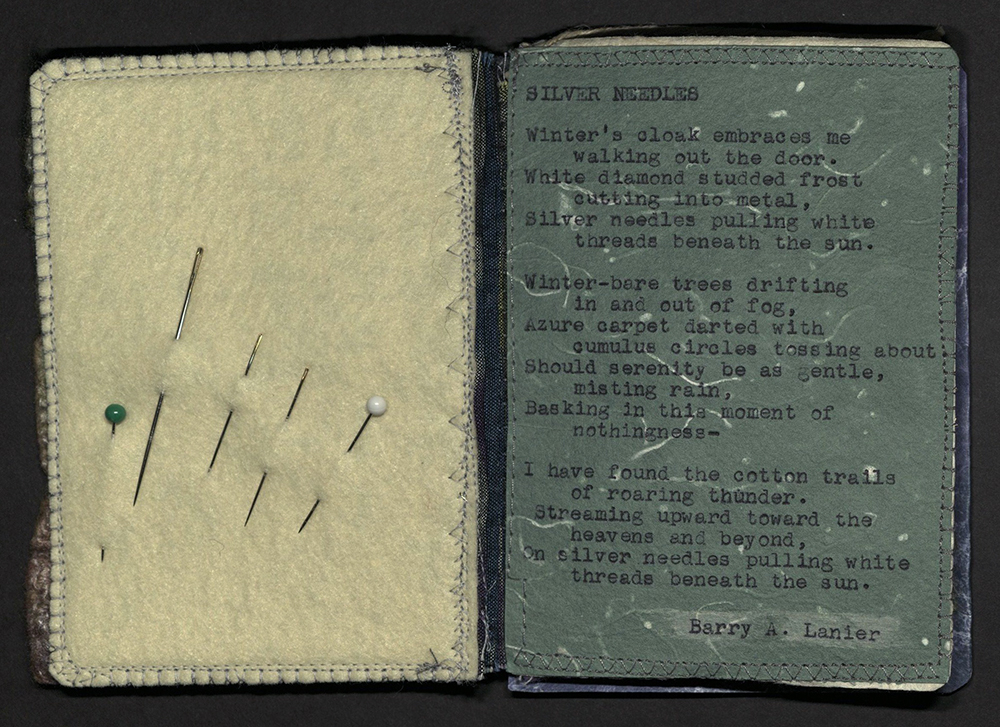

SILVER NEEDLES

Barry A. Lanier

[between 2000 and 2009]

PS3612 A584 S55 2000z

Scraps of paper or cloth can be sentimental. You may hold on to all of them, vowing to find a way or a reason to repurpose them later. Using repurposed cloth, many sewers create specialty needlebooks, decorated with patchwork pieces of different fabrics and sometimes embroidered with designs. These soft, small, portable books not only safely keep your sharp needles in place they can also be reminders of past projects and containers for even smaller scraps.

This needlebook does, in fact, contain needles and pins. But within its patchwork we also find a poem, titled “Silver Needles” and all at once, text and textile become self—referential. Although the poem is not about sewing, it uses the language of textile to weave the imagery of the sky on a winter’s day.

Winter's cloak embraces me walking out the door.

White diamond studded frost cutting into metal,

Silver needles pulling white threads beneath the sun.

Winter-bare trees drifting in and out of fog,

Azure carpet darted with cumulus circles tossing about.

Should serenity be as gentle, misting rain,

Basking in this moment of nature and nothingness —

I have found the cotton trails of roaring thunder.

Streaming upward toward the heavens and beyond,

On silver needles pulling white threads beneath the sun.

Little is known about the history of this little needlebook. Where it came from, when it was made. As for the Georgia poet, Barry Lanier, it is said that he once admitted, when asked about his poetry, “I have no special ambition, other than to give back hopefully a portion of what has been freely given to me, and should my written words help just one person, then my efforts have been a success.”

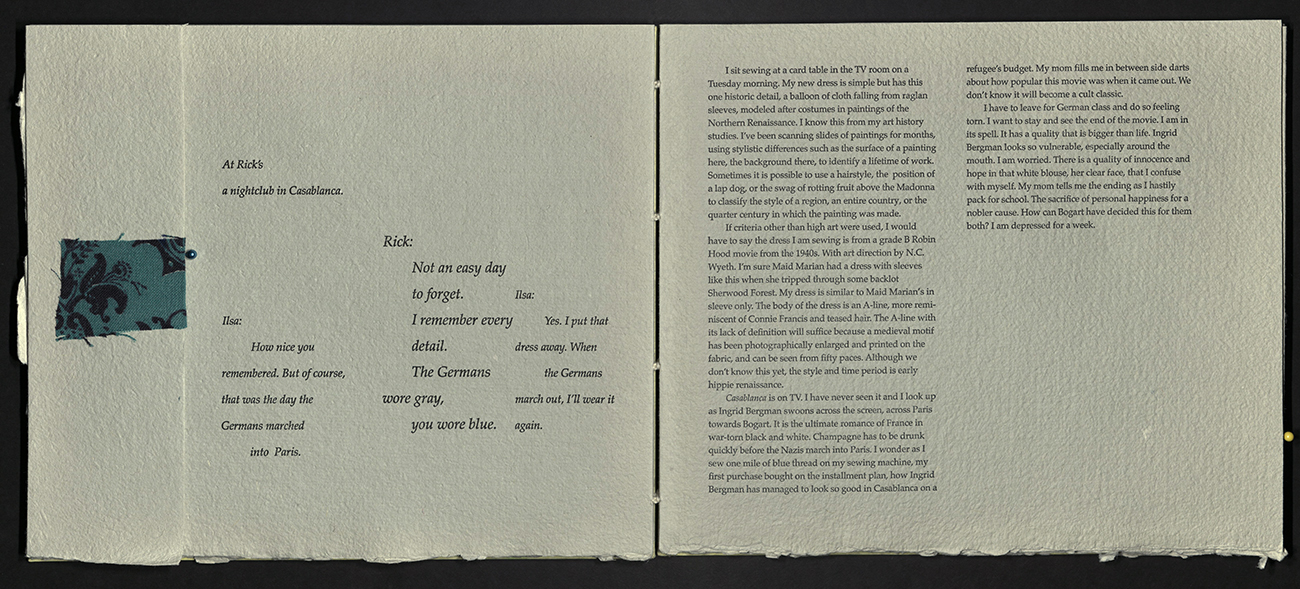

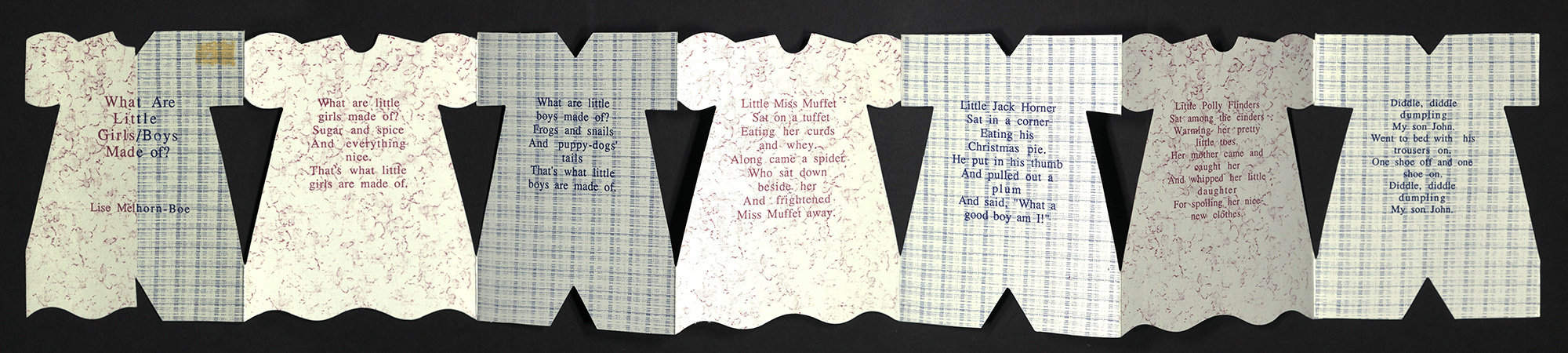

REDRESSING THE SIXTIES: (ART) LESSONS A LA MODE

Susan Elizabeth King

Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Women in the Arts, [2001]

N7433.4 K5 R43 2001

Like the books we read and the outfits we wear, scraps are more than capable of telling a story. Just ask artist Susan E. King. In her book, Redressing the Sixties: (Art) Lessons a la mode, King uses scraps from her collection of vintage clothing to weave the narrative of her journey as an artist — from her beginnings in 1965 as an art student in the United Kingdom to a thirty year stint in Los Angeles, and back again. Somewhere along the way, King became a founding member of the legendary non-profit community art center known as the Women’s Building in Los Angeles. In addition, she headed the Women’s Graphic Workshop and became internationally known for her artist books.

Growing up in Lexington, Kentucky, Susan King was shaped by a family of Southern storytellers, including mothers who prowled antique malls and grandmothers who sewed and tatted lace. In a whimsical recollection of the influences on her life related to clothing and fashion, Redressing the Sixties can be considered part memoir and part cultural artifact, combining original prose pieces with selected texts, plus a variety of fabric samples to adorn the pages. It begins,

“I started the sixties with the requisite wardrobe of wool pleated skirts and matching Shetland sweaters. Jackie had glamorized Mamie’s matronly outfits of the fifties, but we were still expected to wear gloves and hats to church. As the decade began, the wildest I got was a Madras shift with sandals. If worn with the right accessories, I could almost look beat. Like one of the beat girls in a Life magazine photo. It was what I most wanted to be.”

Created for and supported by the Library Fellows of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Fabric swatches are pieces of clothing from the collection of the artists. Paper made by David Carruthers and Company at St. Armand Papeterie, Montreal. The typeface is Palatino. Covers are paste papers made at the press over boards. Sewn in signatures in a non-adhesive binding with visible sewing structure. Edition of one hundred and twenty-five copies, plus artist’s proofs. University of Utah rare books copy is no. 52, signed by the author/artist.

KIMONO / KOSODE

Carol Schwartzott

Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2001

N7433.4 S384 K55 2001

As with Redressing the Sixties, Carol Schwartzott’s Kimono / Kosode was published in 2001 by the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and while the former uses descriptions of clothing to drive the plot, the latter imitates the garment through the form and structure of the book itself.

Bound with a piano hinge binding design and Japanese chiyogami papers, Kimono / Kosode reveals the history of the distinct Japanese garment while simultaneously alluding to the act of wrapping and unwrapping the material around the body of the book — with a cut-out of the iconic t-shaped design highlighting decorative textiles represented by the differents papers of each page.

The first real indication of the kimono’s importance in Japanese culture occurs during the Heian period between 794-1185 AD. It was during this earliest period of artistic enlightenment that a mastery of poetry, calligraphy, and music, along with elegance in dress became essential aspects of court life.

Women were the first to wear kimono style garments. The court lady’s rule of dress was called the kasane—gi, where multiple layers of unlined robes, usually twelve to twenty, were worn over the other. Since the inside of the elbow and the nape of the neck were considered erotic and sensual, each gossamer layer created a complex beauty at the collar and sleeve opening, where the colors of all were visible. A woman usually wore her court dress for several days at a time, not removing it even to sleep.

Kosode means “a thing for wearing.” It is an old name for a form of dress that is now usually called kimono. The cultural aspects of the kosode evolving as kimono also came about because of the increasing influence of women, and this, along with the changeover from a noble ruling class to the samurai and their beliefs, placed more emphasis on simple clothing. As kimono design evolved, the concept was to achieve the original beauty of many robes creating a complex surface design on one single layer of fabric.

With each period in history, the kosode evolved, adapting its design and decorative elements to current style and availability of materials. Stitched or embroidered with silk and metallic threads, patterned with paste-resist foils and stencils, shiburi dyed and ikat warped, printed, or silk-screened, the kosode has many different faces, each showing us a different time and place in the history of Japan.

Created for and supported by the Library Fellows of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Designed and bound by the author. Printed on Blacks Corner Letterpress. Bound in archival boards, Japanese chiyogami papers with a piano hinge binding design by Hedi Kyle.

ONE WOMAN'S SEWING BEE

Linda K. Smith

[United States]: Linda K. Smith, [2002]

N7433.4 S6417 O6 2002

According to Nancy Bradfield, author of Costume in Detail, “The inside of a dress is often as interesting as the outside, and at times more complicated, and to understand a dress fully, a knowledge of the inside is essential.”

Linda K. Smith takes this notion of “the inside” and applies it to herself, creating a collection of descriptive essays about pieces of clothing that she, the “one woman” of The One Woman’s Sewing Bee would like to sew. Her essays are coupled with examples of clothing practices and beliefs, along with some secrets of clothing, all discovered in her readings on the subject. Vignettes of personal narratives make up the third strand of the text, exploring both the universal and personal in the ordinary and basic structure of clothing. Smith views the book as her version of how we weave threads of our lives into a whole.

The three strands of short and historical and personal essays which make up this textually and structurally entwined book are accompanied by hand-stitched paper, bead decorations, and pin-hole patterns made by threadless sewing machine needle perforations. The narrative includes musings on the vest, the everyday dress, the courting dress, the special dress, the fantasy dress, the buttons, the glove, the shoe, and the mended piece.

Laser printed using Quark Express in Hoefler Text with Hoefler Text Ornaments. Hand-stitched paper and bead decorations and pin-hole patterns (from threadless sewing machine needle perforations) adorn the pages. The papers are Esse white; grey, straw-embedded Ogura Chine; gold-on-grey Yuken; and Reversible Unryu/Kozo Momigami all within a Coptic binding of layered Japanese papers. Edition of twenty-five copies. University of Utah rare books copy is no. 3.

QUIPU

Catherine Mutz

San Francisco, CA: Protean Press, 2004

F3429.3 Q6 M87 2004

Designed, printed, and bound by Terry Horrigan. Text typeface is 13 pt. Poliphilus and Blado. Paper is bianco Fabriano Ingres. The etching was drawn and engraved in plexiglass by Terry Horrigan, printed, and then folded in a style known as the “Turkish map” fold. Bound in Lokta fiber paper from Nepal. Ann Miller developed calligraphic letters and elements. Edition of forty copies. University of Utah copy is no. 31.

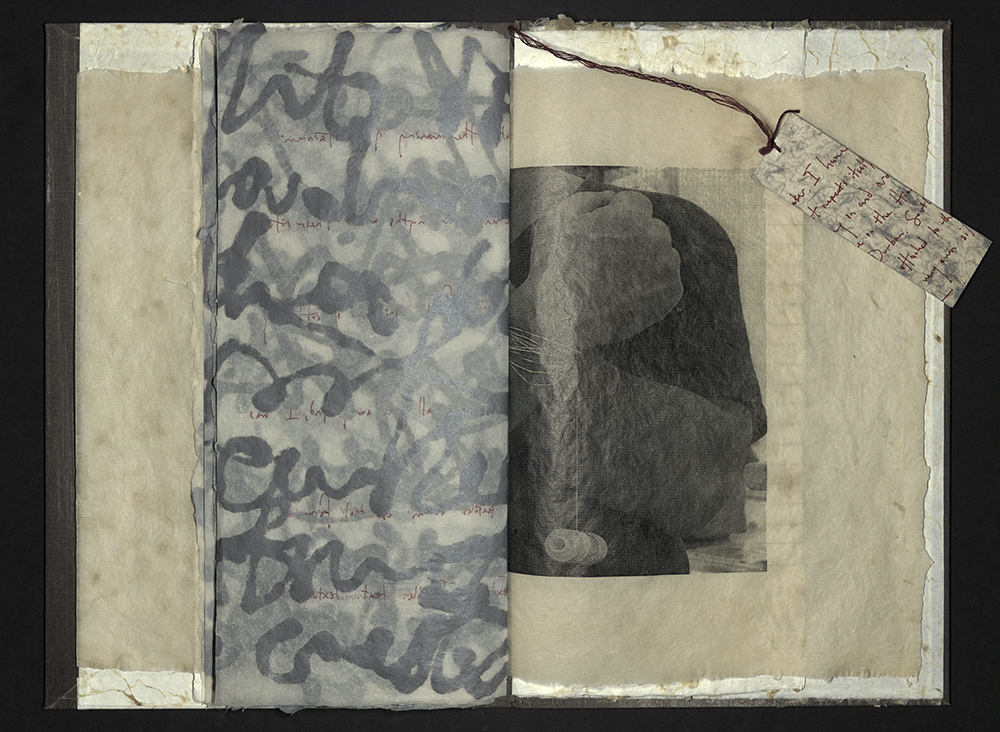

CLEW

Robin Ami Silverberg

New York, NY: Dobbin Books, 2004

N7433.4 S548 C5 2004

The guiding thread, as it were, for this selection of books has been a focus on textiles, whether explicitly or implicitly. This next book uses this notion of a guiding thread, or clew to reflect on the deeper meaning of the marriage tree located on the grounds of a Hindu temple in South Africa, and the ritual of young women wrapping the tree with silk threads as a prayer to acquire a husband.

The prose, printed in thin red lines of red across translucent paper, evoke a thin strand of thread moving across the page. Meanwhile, the illegible bolder black commentary might suggest a tangled ball of yarn — further depicting the author’s conflicted views of the ritual. The text reads,

I remember then being struck by the image of all those shimmering threads against the dark. And — it was so hot and we were sitting on a low stone wall. I allowed my mind to drift to examples of “wrapped” art — from Christo to Windsor. I considered several evocative memories — like the wrapped tall candlesticks on the altar in a Roman church, and those balls in Yucatan that were made of layers upon layers of strings or rubber bands. Each recollection made me look longer at those threads —

I thought pityingly about those young women for whom marriage is an essential and ultimate goal. But: don’t we also say “tying the knot”? What about tying a yellow ribbon around that old oak — not to mention all the post—9/11 memorials that cropped around town. I am sure that I never understood the evocative language of material, form and presentation. I was certainly aware of the parallel symbols of bondage, but I am quite sure that I was naive to which factors encapsulated the meaning of containment.

I was unable to either comprehend how myths with their rituals can be so transcendent or of the role of the initiated in sustaining their illusions… even after the dreams have all gone away. And, I was totally unaware of the role of textiles as an essential form of women’s communication. Text. Texture. Textile. Text. Texture. Textile.

The "ball of thread" meaning of clew has been with us since before the twelth century. In Greek mythology, Ariadne gave a ball of thread to Theseus so that he could use it to find his way out of her father's labyrinth. This, and similar tales, gave rise to the use of clew for anything that could guide a person through a difficult place. This use led in turn to the meaning "a piece of evidence that leads one toward the solution of a problem." Today, the spelling variant clue (spelled c-l-u-e and appeared in the sixteenth century), is the more common spelling variant for the "evidence" sense.

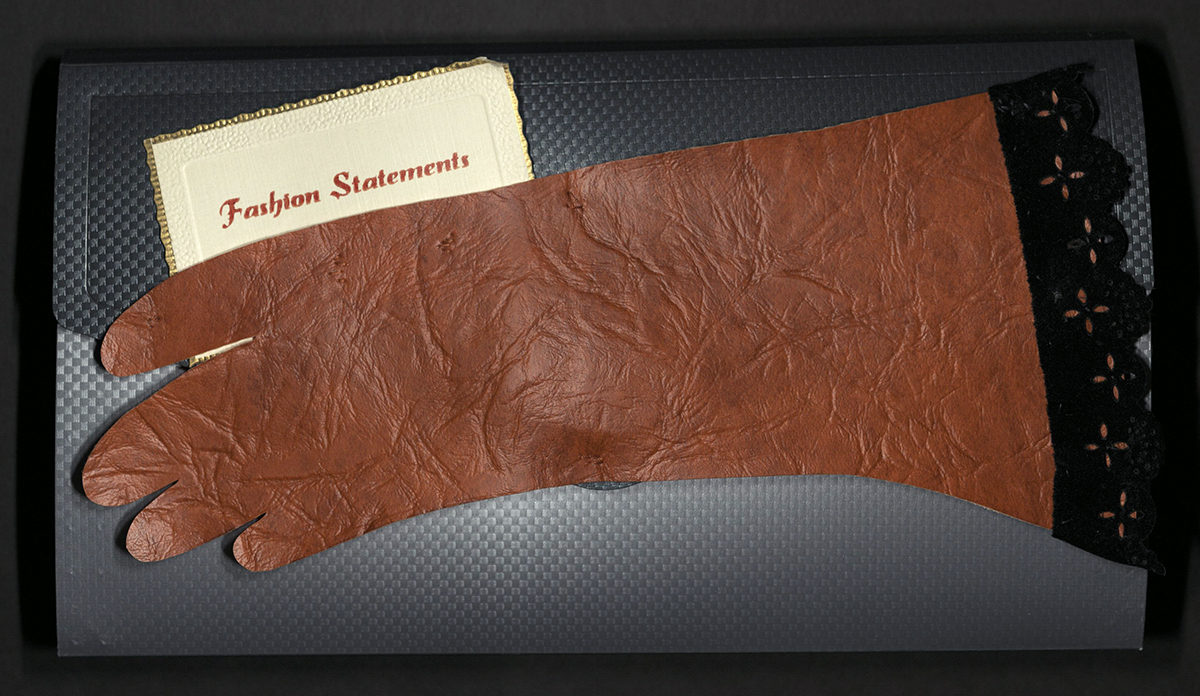

FASHION STATEMENTS

Frederica Postman and Bonnie Stone

Los Altos, CA: P’Nye Press, 2005

N7433.4 P68 F37 2005

Designed in the appearance of a clutch, Fashion Statements brings together the stories of more than two dozen women. In order to provide anonymity and privacy, the book artists substituted some contributor's names for the names of famous fashion designers. The stories respond to the ways in which clothing and fashion are bound up in the relationships between mothers, daughters, sisters and friends. From bridal gowns, paper dolls and heirlooms to the little black dress, hats, and aprons, this artist’s book makes a ‘statement’ on how fashion influences and is influenced by society’s expectations.

Fashion Statements is printed letterpress. The text is set in Italian Old Style cast by Monroe H. Postman on a Monotype caster with a Macintosh Computer interface. Edition of sixty copies. University of Utah copy is number 27.

NOUS TISSONS

Kitty Maryatt

[Claremont, CA]: Scripps College Press, 2006

N7433.4 S37 N6 2006

There is no doubt that the role of textiles is an essential form of women’s communication, but would it surprise you to know that textiles, specifically woven ones, are what allow us to communicate digitally today. It’s true, the origin of modern computers dates back to an early eighteenth-century invention commonly called the Jacquard machine or the Jacquard loom.

The Jacquard machine is a device fitted to a loom, called a head, that simplifies the process of manufacturing woven textiles with complex patterns. The machine is controlled by a chain of punched cards, laced together into a continuous sequence. Multiple rows of holes were punched on each card, with one complete card corresponding to one row of the woven design. These cards were replaceable and were used to control a sequence of operations, allowing only certain hooks to move through holes in order to grab the appropriate thread and create the design.

Though based on earlier inventions by Basile Bouchon, Jean Baptiste Falcon, and Jacque Vaucanson, this mechanism was fully developed by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1804, which is why he is often cited as the inventor. The Jacquard machine and loom revolutionized the textile industry and made possible the automatic production of unlimited varieties of pattern weavings, among so many other things.

The Jacquard head, and its replaceable punched cards, is considered to be an important step in the history of computing software. The ability to change the pattern of the loom's weave by simply changing cards was an important conceptual precursor to the development of computer programming and data entry.

Nous Tissons, translated from the French as “we weave” is a collaborative project produced by The Scripps College Press and Clair Van Vliet, which includes various texts on the subject of weaving, and incorporates Van Vliet’s unique book-making techniques. An additional narrative about Joseph Jacquard and the invention of his loom is both textually and structurally “woven” throughout the book.

Arches cover is said to reflect the interwoven narratives while the Stardream cover which presents the Jacquard anecdotes functions to hold the book together. Typeset by hand and printed on Vandercook letterpresses by students at the Scripps College Press and printed in an edition of one hundred and two copies.

ADA'S ECHO

Kelly Wellman

[California?]: This Is My Body Press, 2001

N7433.4 W448 A32 2001

British inventor, Charles Babbage, had heard of the Jacquard loom and saw the potential in the use of its replaceable punched cards for solving math problems. But although he was a brilliant inventor, he could never quite grasp the mechanism of the loom. Perhaps this is because he did not speak the language of textiles. Enter Ada Lovelace, the abandoned daughter of poet Lord Byron. Sometime in 1833, Babbage met a young Lovelace at a party. They became friends and, as the story goes, Babbage showed Lovelace a small prototype of the computing machine he was working on at the time, inspired, in part, by the Jacquard loom.

Unlike Babbage, Ada Lovelace realized the Analytical Machine’s ability for uses other than mathematics, but can be used, instead, as a system of rules that can be applied to a vast range of intellectual pursuits. Lovelace helped Babbage refine and direct his ideas, editing, footnoting and often correcting his work. And Lovelace and Babbage carried on a lifelong correspondence. Babbage devalued Lovelace, calling her his “interpress” and “the enchantress of numbers.”

Beyond his ability to recognize Lovelace as his equal, Babbage lacked some serious social skills and often alienated potential benefactors. They were on the verge of creating the world’s first working computer, but the lack of funding halted any further progress. In 1843, tens years after they met, Lovelace wrote a long letter to Babbage urging him to let her handle negotiations with the backers. He politely rejected her offer.

Imagine how different the world would be today if he said yes.

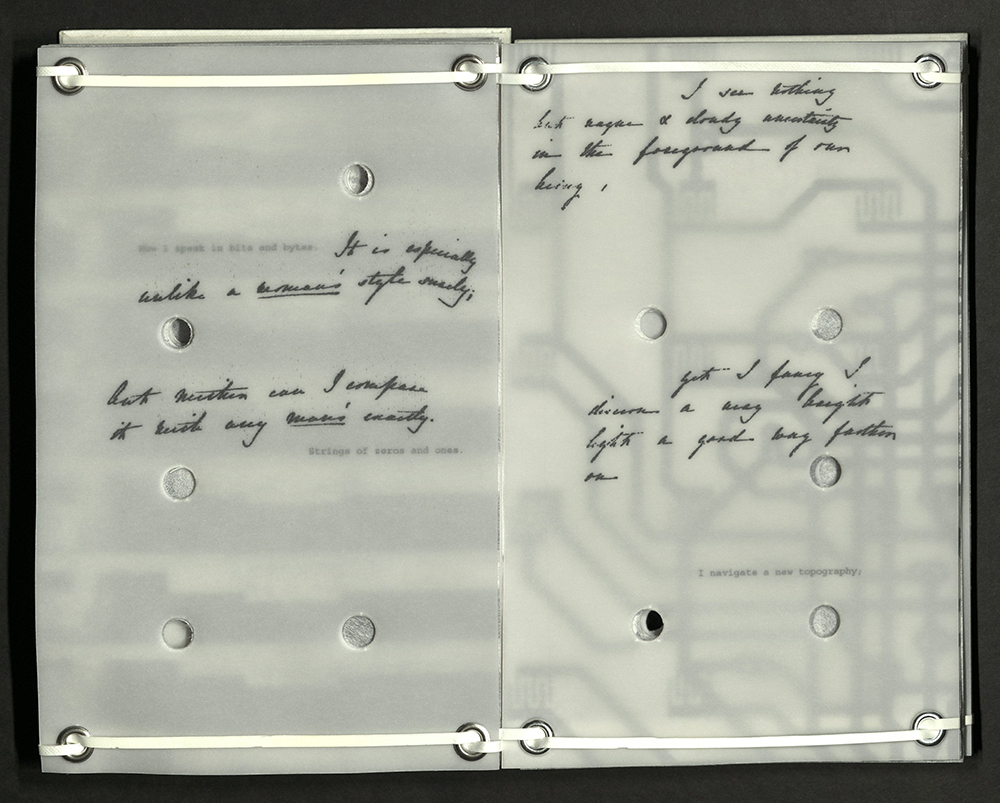

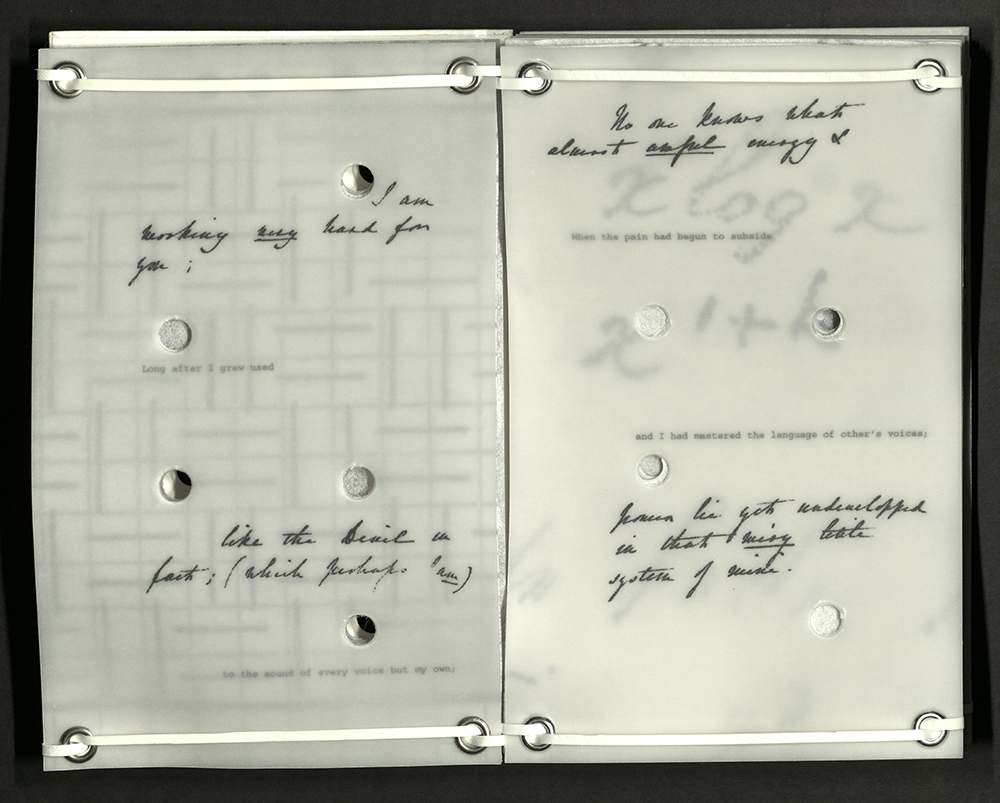

The dream of the Analytical Machine, or the Difference Engine as it was sometimes called, was never fully realized. And it took over one hundred years for Ada Lovelace to be recognized for her contributions to the field of computer programming. In 1977, a new computer programming language was named “Ada” in her honor. She is now widely acknowledged as a computer pioneer. Ada’s Echo, created by Kelly Wellman, includes text excerpted from Ada Lovelace’s letters to Charles Babbage. Translucent paper forms the top and main text page through which the secondary text and shadowy images are seen. By layering the pages, progress is depicted as a process of accrual, in which many hands and voices contribute over time.

The modified accordion binding was produced by weaving pages together through grommetted corners (at both the head and foot) with plastic paper strips. Pages are punched with different configurations of holes to recall punch cards.

THE DESERT

Jen Bervin

New York, NY: Granary Books, 2008

N7433.4 B47 D47 2008

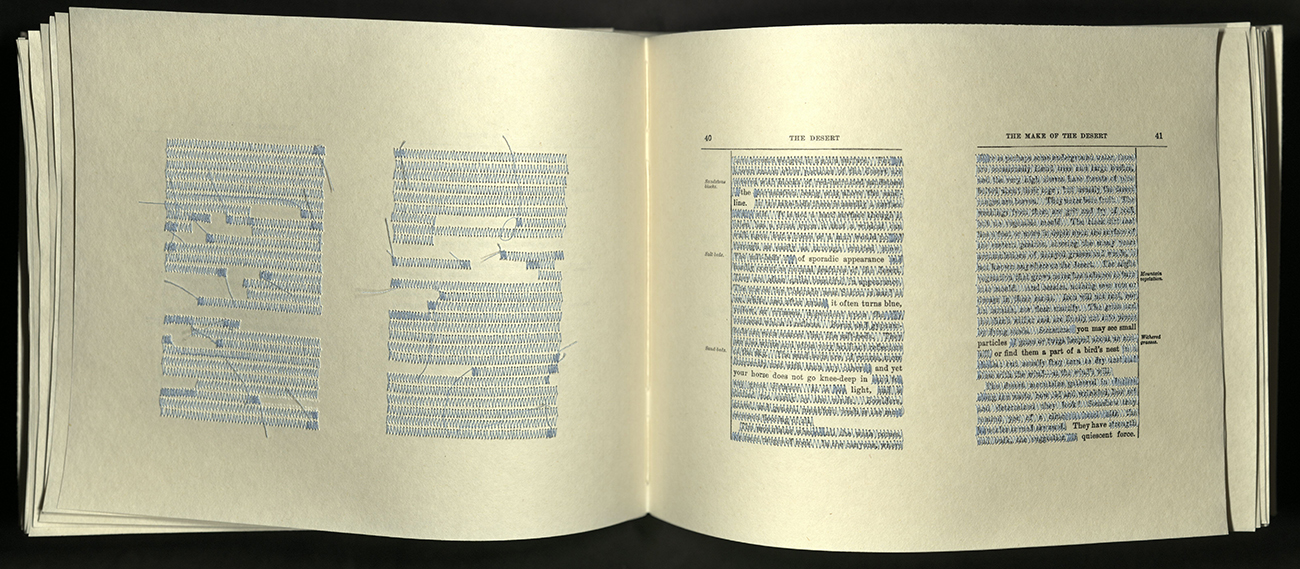

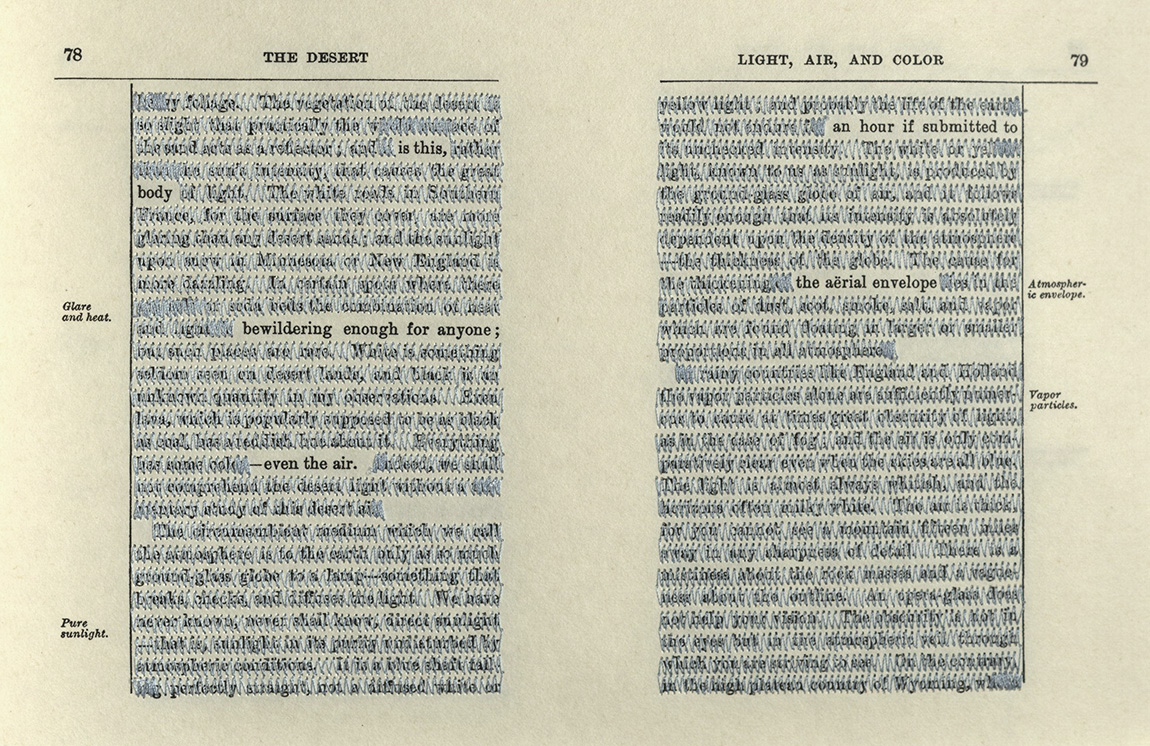

The erasure of Ada Lovelace from decades of history is not excusable. On the other hand, erasure, as a form of poetry, is something that can imbue new meaning into old words. In The Desert, poet and visual artist Jen Bervin works in the tradition of poetic composition by erasure by meticulous sewing, row by row, across 130 pages of text.

The text hidden under Bervin’s pale blue thread is John Van Dyke’s prose celebration of American wilderness titled The Desert: Further Studies in Natural Appearances, first published in 1901. Van Dyke, an art historian, claimed to have spent three years in the American Southwest desert with only his fox terrier for company and a pony for transportation. According to Van Dyke, he carried with him a rifle, pistol, hatchet, shovel, blankets, tin pans and cups, dried food, and a gallon of water. Despite the book being a huge success, it turns out Van Dyke’s story was fiction, rather than fact. The truth was that Van Dyke saw most of this great desert while looking out of windows of trains on his way from one first-class hotel to another.

What Jen Bervin does to Van Dyke’s romantic rhapsody is breathtaking. Using over five thousand yards of thread, Bervin creates her own elemental landscape, with atmospheric fields of pale blue zigzag stitching to construct a poem “narrated by the air” — “so clear that one can see the breaks. The poem that emerges from Van Dyke’s desert was first composed at James Turell’s Roden Crater in Arizona, on the Wave Books Poetry Bus Tour in October 2006. Thinking of Turrell, Bervin wrote: “The great get on with the least possible, and suggest everything by light.”

The text of the book was digitally printed by Jan Drojarksi in Brooklyn on handmade Twinrocker abaca paper, the books were machine-sewn by Bervin and a team of assistants in Seattle, and bound in hand—punched abaca covers by Susan Mills in New York in an edition of 40 copies. Housed in a hinged archival case. Issued in a wrapper of white muslin cloth and white felt stitched together with blue thread.

THE DICKINSON COMPOSITES

Jen Bervin

New York, NY: Granary Books, 2010

N7433.4 B47 D53 2010

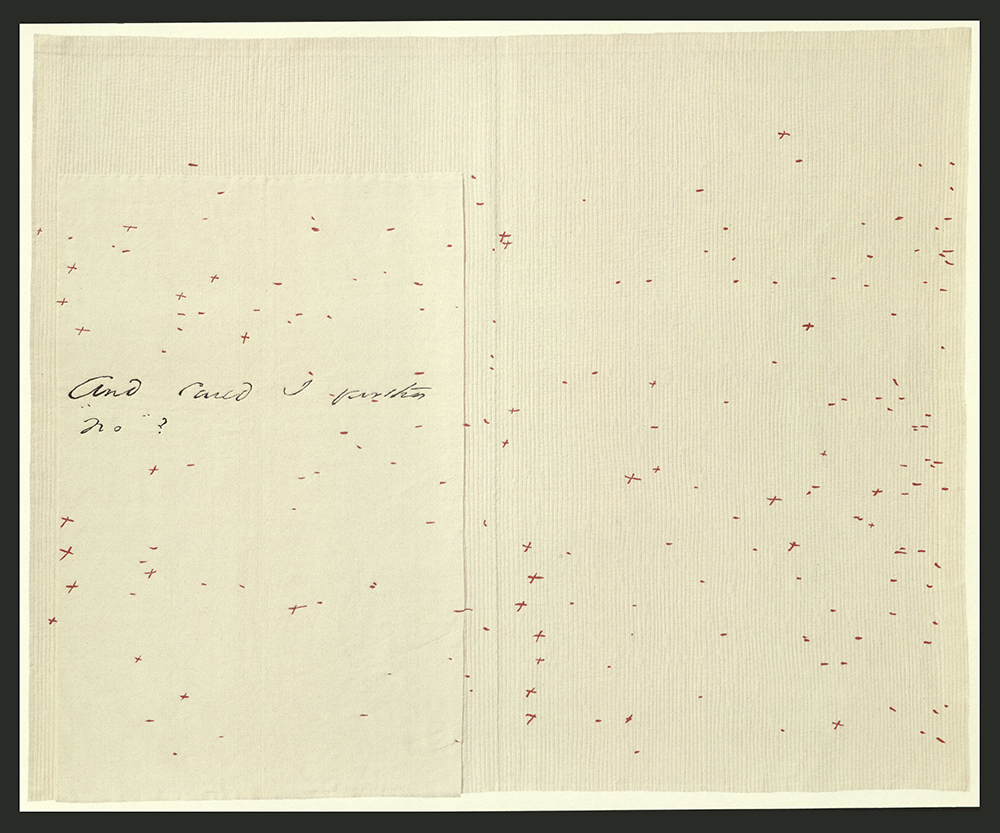

Many of Jen Bervin’s projects seek to “unstitch the seams between text and textile.” In The Dickinson Composites, Bervin once again uses stitches, but this time it is to mend the things that have been taken apart and taken away, to put them back together again. The things I am talking about are Emily Dickinson’s poetic marks — the familiar dashes, ubiquitous crosses and plus signs, or the variant words which are scattered throughout her manuscripts but rare, if ever, are reflected in the print editions of her poems.

Rather than erase, Bervin foregrounds these oft-omitted marks to see what patterns formed when all the marks remained in position, but were isolated from the text. To do so, Bervin first scanned the original manuscripts, written by Emily Dickinson sometime between 1858 and 1864. The handwritten poems were composed on stationary folios into forty packets — later called fascicles — and were stab-bound with red and white twist thread.

The manuscripts were digitally enlarged in order to convey the exact gesture of the individual marks, which were digitally rendered, projected, and then transferred onto cotton batting to make a series of large-scale embroidered works. The series includes five 6x8 quilts, whose titles identify their relationship to Dickinson’s fascicles. The quilts were prepared with a hand-sewn center line and machine-sewn lines that replicated those of the light-ruled paper, while the marks were embroidered in handspun and hand-dyed silk thread.

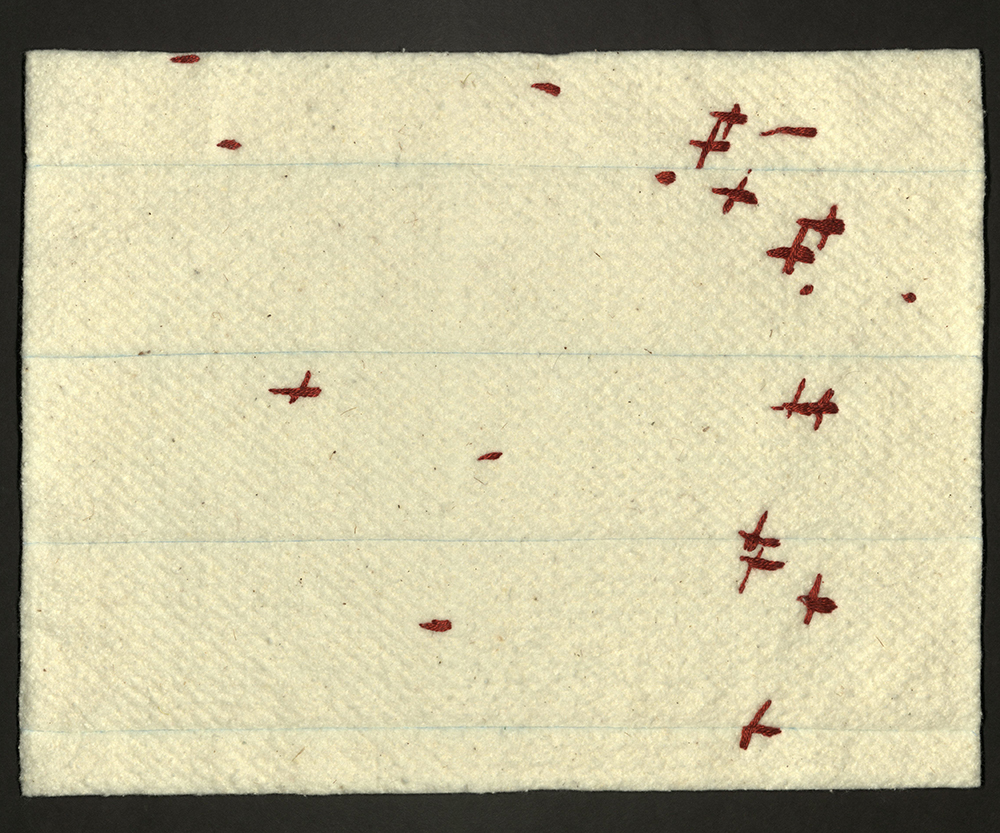

Granary Books later published Bervin's works as this limited-edition artist's book, titled The Dickinson Composites — an artist book that focuses on a series of large-scale quilts Jen Bervin made by embroidering the poet Emily Dickinson’s unusual punctuation markings from her fascicles. The box, printed with enigmatic red crosses and dashes, contains two sewn samples (excerpts made at the same scale, in the same materials using the same methods as the quilts), large prints of each quilt, and a nested booklet. Like Dickinson’s manuscripts, the box and the works therein are encountered entirely without titles. In the booklet, an essay by Bervin elucidates Dickinson’s variant marking system in her poetry manuscripts and provides further context for the quilts.

Each box includes: A lignin-free, drop-front archival box printed with quilt-scale fascicle marks in red. Two machine-sewn and hand-embroidered samples — excerpts from Composites 28 and 38, made at the same scale, in the same materials using the same methods as the quilts. Images In the booklet show the hand—sewn sample in relation to the full quilt, with the excerpt area marked. Large color prints of all six quilts: The Composite Marks of Emily Dickinson’s Fascicle 16, 19, 28, 34, 38, and 40. An unbound 16-page booklet with an essay on the variant marks, images of Dickinson’s manuscript poems, and process and installation images of the quilts. The booklet is housed in a pocket printed with marks and sewn with a cotton tape lift.” Edition of fifty copies.

In a New Yorker article, about Bervin’s work related to Emily Dickinson, she is quoted as saying, “It seemed to me that what she was doing was much more interesting than what was being done to her.”

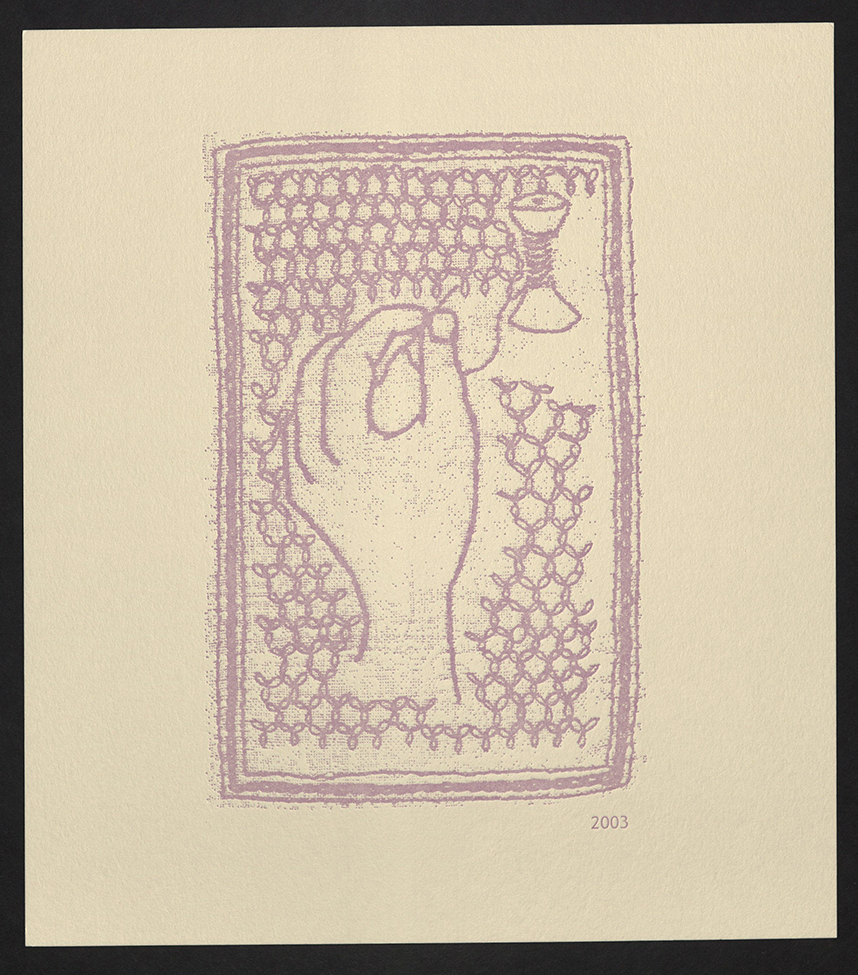

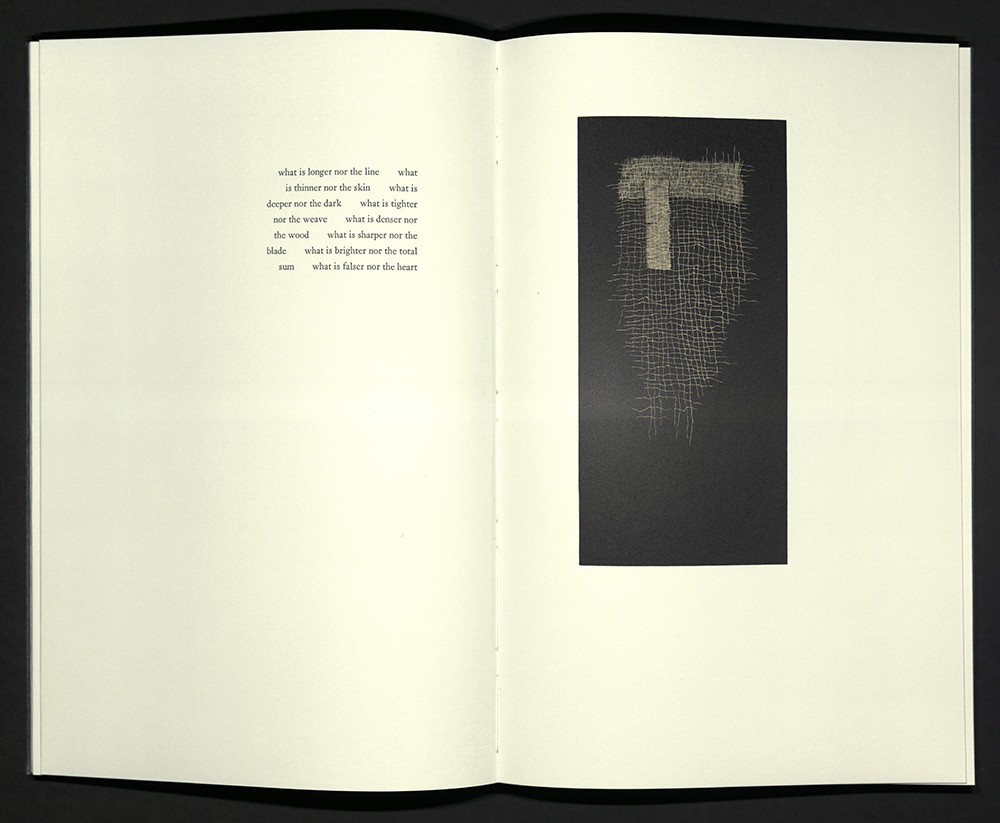

DRAFT NOTATION

Jen Bervin

[New York, NY]: Granary Books, 2014

N7433.4 B47 D73 2014

In a later project, Jen Bervin drew inspiration from textile artist and printmaker, Anni Albers. With a background in the Bauhaus school of art, German-born Albers had an incredible ability to blur the lines between traditional craft and fine art. When Albers was teaching at Black Mountain College, so-called “typewriter studies” formed part of her curriculum. The designs — a sequence of aligned slashes, colons, underscores, the alternation of upper-case and lower-case S’s — imitated the gridded space and the interplay of warp and weft and aided in creating what Albers called “tactile-textile illusions.”

As with Dickinson, Bervin was intrigued by Albers’ markings and she set out to do her own experimentation with typewriters, texts, and textiles. Draft Notation is the compilation of typed studies made on several typewriters over the course of the year. It includes four pale green books with a total of 57 typed studies reproduced in letterpress, a unique typing on red board, facsimiles of nine studies made on different typewriters, a typed process note from Jen Bervin, and a colophon — all contained in a sail cloth-covered clamshell box.

The title refers to the pre-weaving design diagrams a weaver creates or consults to plan her work on the loom. Some of the notations were created while listening to poetry recordings and interviews, hence the quotations that appear. Bervin was also heavily influenced by early mending samplers, like the ones we have already seen, wherein complex woven patterns are replicated with a needle and thread to show off the darning skills of an embroider.

Within Bervin’s Draft Notations there is an incredible amount of intertextuality to sift through, even when there is no text present. Sometimes the deeper meaning is found elsewhere. In the words of Anni Albers, “Wherever meaning has to be conveyed by means of form alone, where, for instance, no written language exists to impart descriptively such meaning, we find a vigor in this direct, formative communication often surpassing that of cultures that have other, additional methods of transmitting information.”

Letterpress printed by Friedrich Kerksieck. Edition of seventy-five numbered copies. University of Utah rare books copy is no. 29

WINTER COUNT

Anne Greenwood

[Portland, OR]: [A. Greenwood], 2008

N7433.4 G744 W56 2008

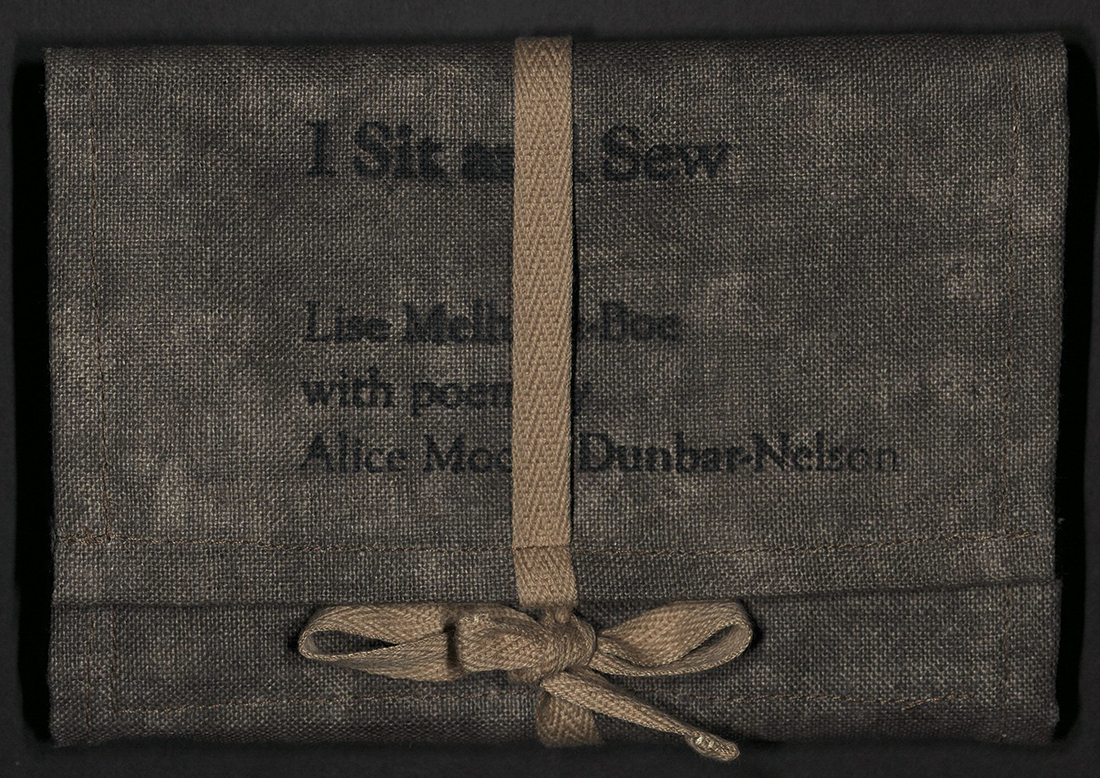

Anne Greenwood’s Winter Count provides us with a phenomenal example of how other cultures communicate and transmit information among generations. Among several tribes on the Northern Plains, the passage of time was marked by noting a single memorable event — recorded pictographically — on a buffalo or deer hide. It was called the winter count, because the year ended when winter was over and new life began in the grasses and trees of the plains. Winter was the opportune time to look back over the year and record its history.