Messenger Of Thought

Treasures from the Rare Middle East Collections

Messenger of Thought Checklist

Curated by Luise Poulton, 2011

Exhibition poster designed by David Wolske, 2011

Digital exhibition produced by Alison Elbrader, 2012

Format updated by Lyuba Basin, 2020

“The pen is the ambassador of intelligence, the messenger of thought, and the interpreter for the mind”

–

Islamic writer on calligraphy

The written word records man's intellectual and spiritual journey. Words, whether written on clay, papyrus, parchment, or paper, are a lasting memorial of humankind. If words are the essence of books, the materials used and the technologies developed to write those words are the building blocks of a captured culture. In books, verbal collaborates with visual, textual with textural. This collaboration enhances meaning and invites intimacy between writer and reader. The arts of the book – papermaking and decorating, calligraphy, illumination, binding, were highly developed in Middle Eastern culture early in its history – in the ancient lands in which the written word was first developed, where papyrus and pen were first used and artwork was first added to elucidate the text. The elegant Arabic alphabet lent itself to numerous decorative forms and abstract patterns, entrancing the eye even when direct images could not. From ancient times to the present, the written word and the craft of Middle Eastern bookmakers has established law, recorded history and myth, inspired faith, stimulated intellectual exploration, and created bonds between cultures both east and west.

Writing began somewhere during the third and second millennia BCE in Sumer between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in what is now Iraq. Among many things, the Sumerians recorded history; business and legal documents; mathematics; and zoological, mineralogical, and botanical studies. Most of what survives today of their writings consists of lists – things like inventories and tax collections. Mesopotamian writings also included myths, epic tales, hymns, lamentations, proverbs, and fables. One of the world’s first and greatest recorded epics, full of heroes, gods, love, and adventure – The Epic of Gilgamesh – was written down on clay tablets. Sumerians used the clay deposited onto the wide, flat riverbeds for writing material. They mixed the clay with straw and water. While it was soft, they formed it into shapes and then used a stylus, a pointed stick, to make marks, the earliest writing system, now called "cuneiform." The clay was baked hard in the sun and, later, in kilns.

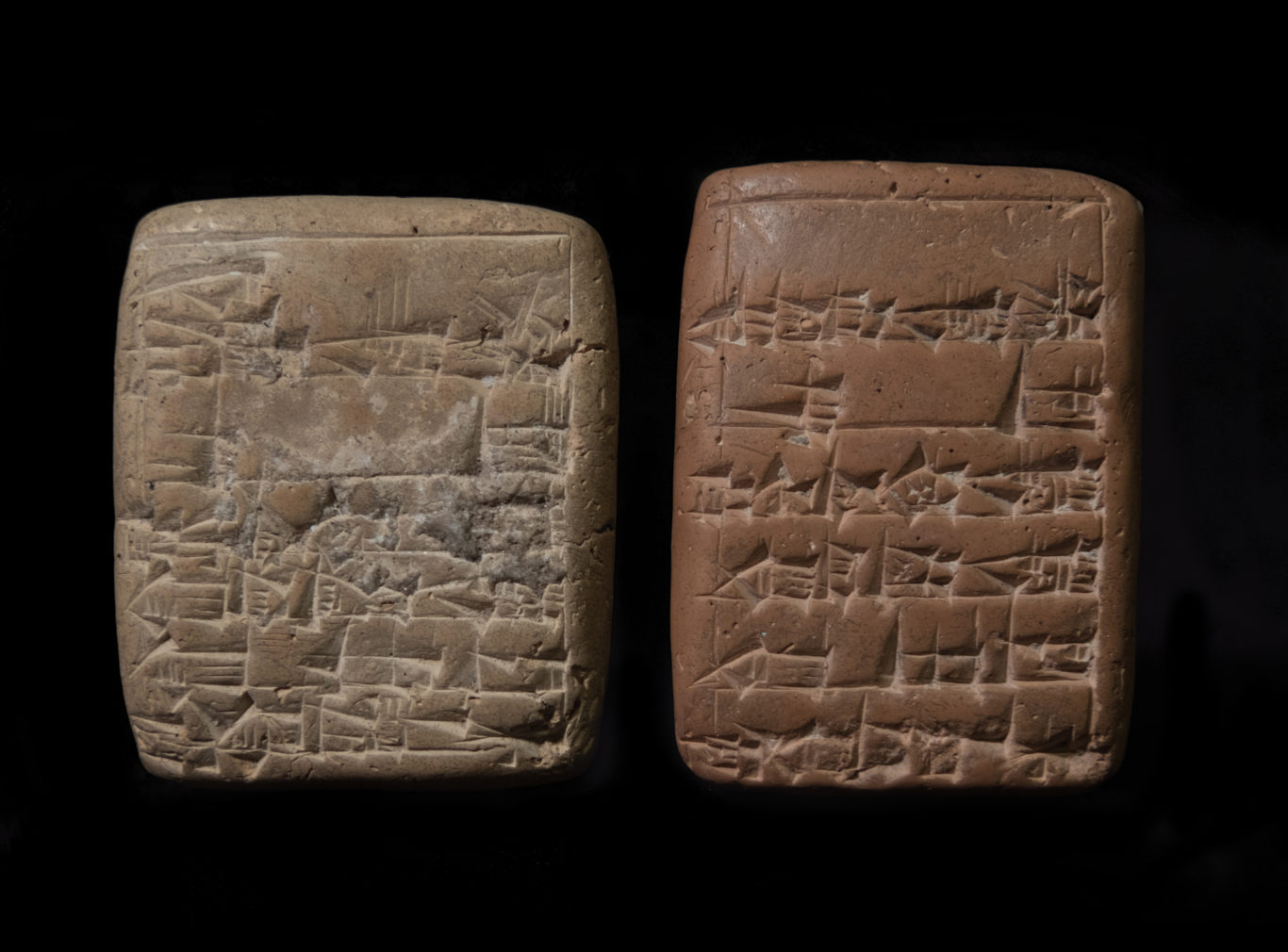

SUMERIAN CUNEIFORM TABLET OF THIRD DYNASTY OF UR

dated to King Amar-Suen of Ur, year 2 (ca. 2045 bc)

PJ3824 B33

The tablet records an amount of a grain (lillan"-grain) for provisions for the funerary cult of the former “lords,” that is the rulers, the en-priests and priestesses. The grain was issued from the mill by an official named Arad and received by an official Ur-mes with the title “beer libator.” This title was used specifically for an official who performed libations during the funerary banquet for the deceased rulers. Some archeologists believe that the symbol for kash, or beer, used on trading i.o.u.’s pressed in clay, was one of the first of what would become the Sumerian writing system. From the Kenneth Laurence Ott Collection donated to the Okanogan County Museum, Washington.

PALACE DEDICATION INSCRIPTON OF KING SIN-KASHID...

Old Babylonian period, c. 1900-1700 BC

Seven lines of Sumerian cuneiform, six on obverse, one on reverse. The text of the inscription is known from 174 duplicates (identified in scholarly literature as Sin-kashid RIM E4.4.1.2): “Sin-kashid, mighty man, king of Uruk, king of Amnanum, built his royal palace (“a palace of his kingship”). The inscription was intended for foundation deposits, and were immured in the walls of the royal palace in great numbers. Some are written on small clay cones, other on clay or stone tablets. There are also many others expanded by a few lines of royal epithets. Uruk was one of the most ancient cites of Sumer. The Amnanum were a tribe of West Semitic Amorite-speaking nomads who had come into southern Mesopotamia several centuries earlier. Thanks to Dr. Renee Kovacs for the translation of our clay tablets.

Old Babylonian period, c. 1900-1700 BC

Seven lines of Sumerian cuneiform, six on obverse, one on reverse. The text of the inscription is known from 174 duplicates (identified in scholarly literature as Sin-kashid RIM E4.4.1.2): “Sin-kashid, mighty man, king of Uruk, king of Amnanum, built his royal palace (“a palace of his kingship”). The inscription was intended for foundation deposits, and were immured in the walls of the royal palace in great numbers. Some are written on small clay cones, other on clay or stone tablets. There are also many others expanded by a few lines of royal epithets. Uruk was one of the most ancient cites of Sumer. The Amnanum were a tribe of West Semitic Amorite-speaking nomads who had come into southern Mesopotamia several centuries earlier. Thanks to Dr. Renee Kovacs for the translation of our clay tablets.

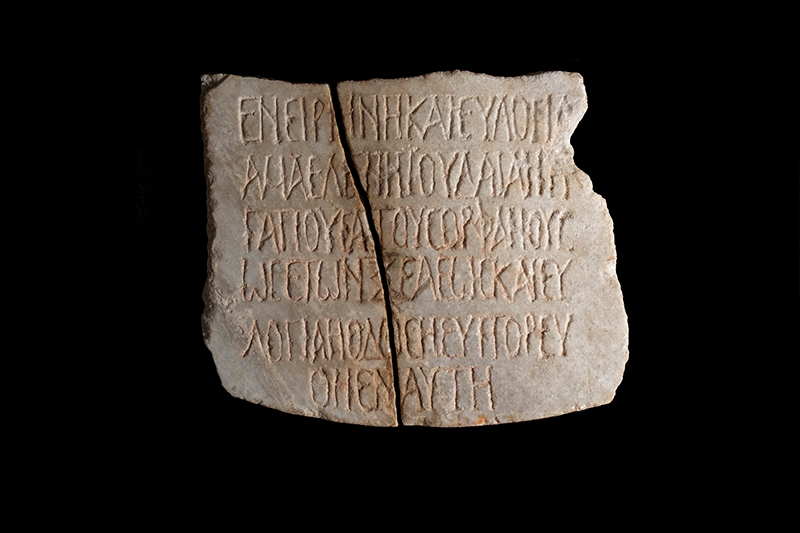

COPTIC INSCRIPTION ON STONE SLAB

ca. 200 – 300

Uncataloged

Coptic inscription in a number of lines on a stone slab, divided into two sections, but appearing to be complete. Dating from the dawn of the use of the Greek alphabet, Coptic replaced the ancient Egyptian Demotic script. This inscription has not been translated. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

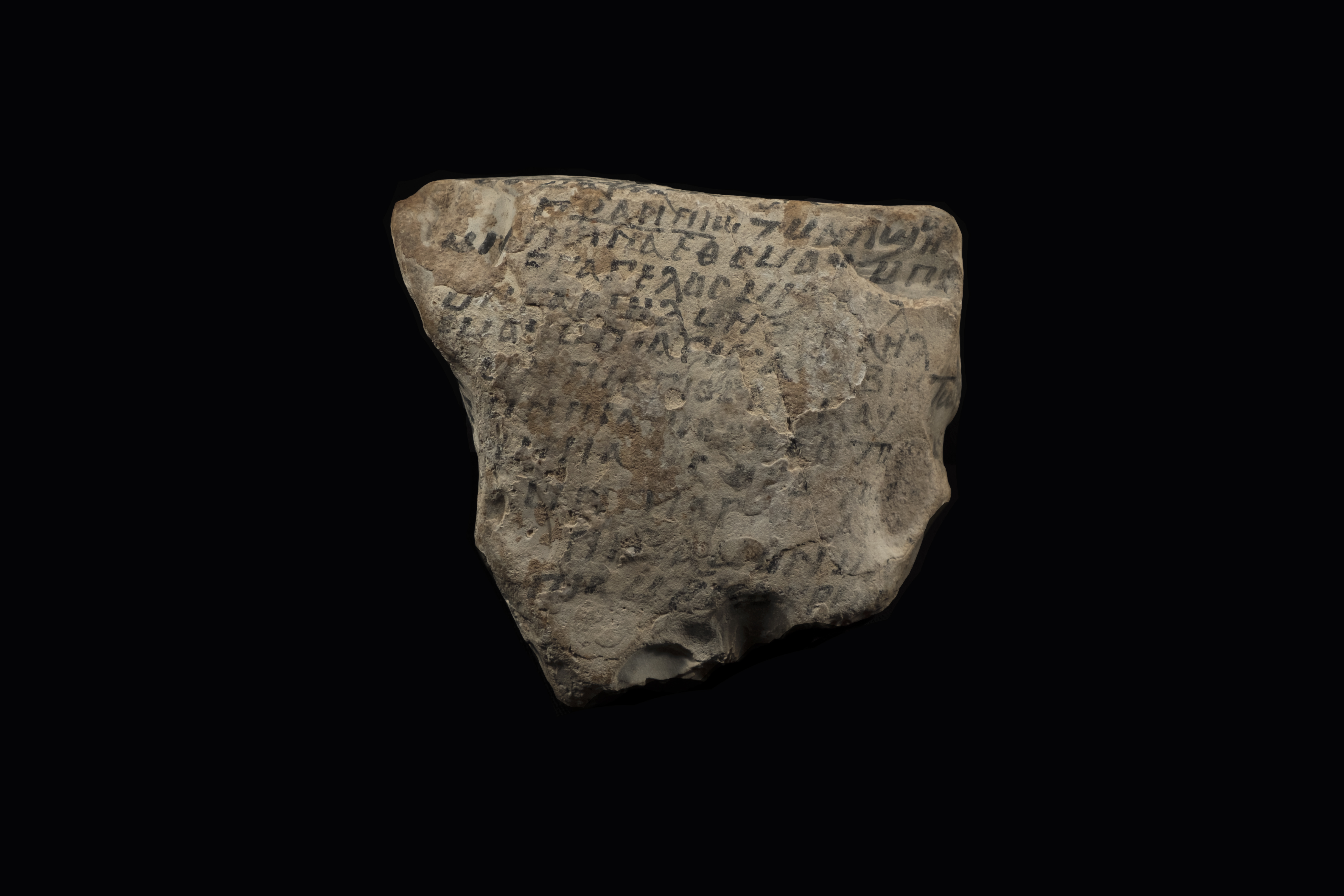

WHITE STONE SLAB WITH COPTIC INSCRIPTION

ca. 200 – 300

Uncataloged

Coptic inscription written in the third or fourth centuries on a piece of irregular white stone. The black ink inscription, not yet translated, consists of eighteen lines and appears to be a complete text. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

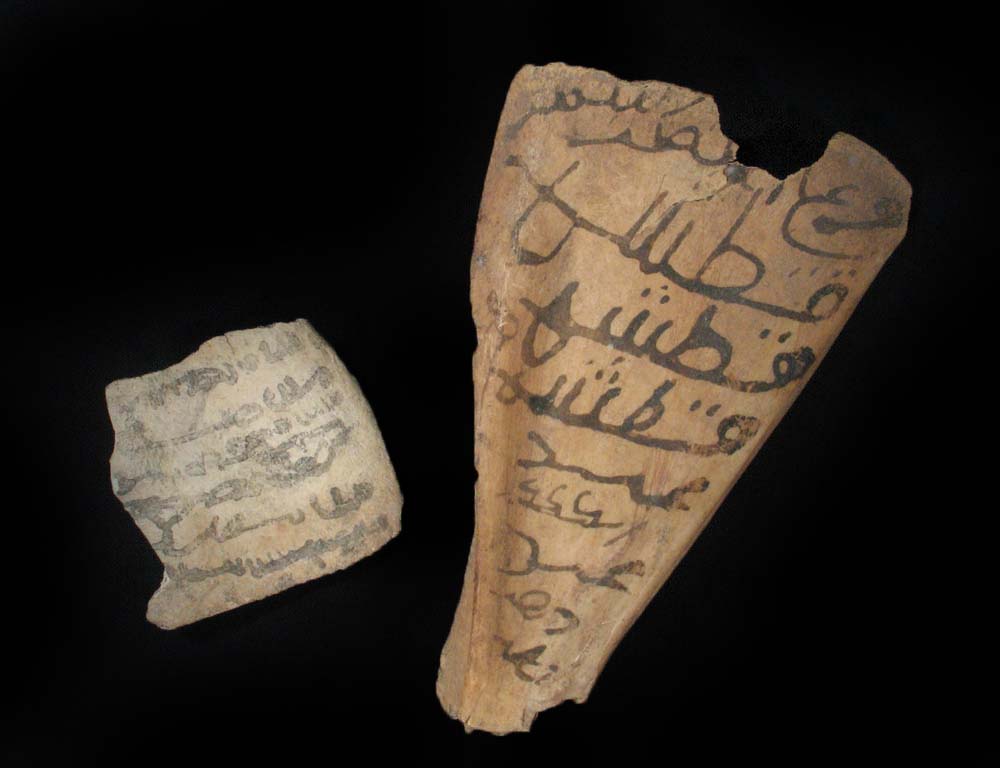

ARABIC SCRIPT ON BONE

Uncataloged

The script on the larger bone appears to be a writing exercise, with repeated words “Qatshah” and “Muhammed.” Qatshah is both a place name and a personal surname. It seems that someone named Muhammad Qatshah, perhaps a child or a newly literate Bedouin, was practicing the writing of his name. Although neither of these pieces has been dated, and it is unlikely that they are from antiquity, they represent an ancient Arabic tradition of using bone as writing material. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

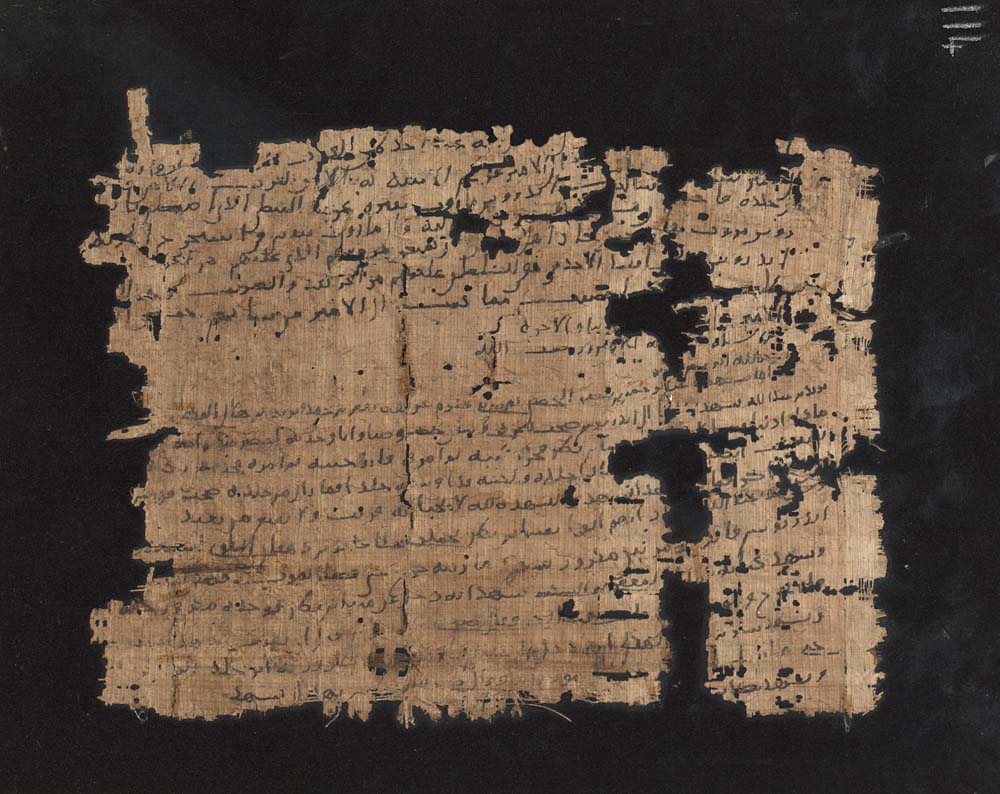

A record about a dispute over the taxes due on an administrator’s estate. This fragment was dated by tracing the change in the meaning of words over time. Technical terms used in this fragment have been dated by collecting data from a large corpus of Arabic tax receipts and leases of agricultural lands. A term found in this document meaning “tax in kind” (dariba) in the early Arabic papyri indicates a terminal date of 798 CE, the latest dated Arabic document extant in which this term is used. Another term found in this document, for the administrative “authority” (sultan), was used no later than 835 CE in any dated document. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

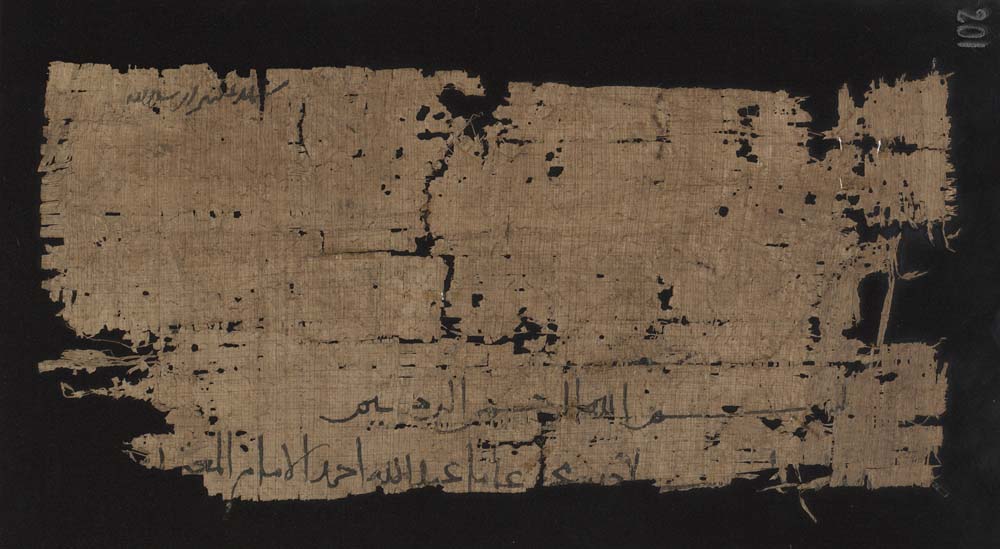

The one surviving line on this document is addressed to the Finance Minister of the Abbasid Caliph Mu’tamid. Papyrus was recycled. A later document was written on the other side of this piece. The longer text on side B records an agreement to supply a day laborer for hire, prorated by the month, for seventeen days, with a commission deducted from the day laborer’s wages. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

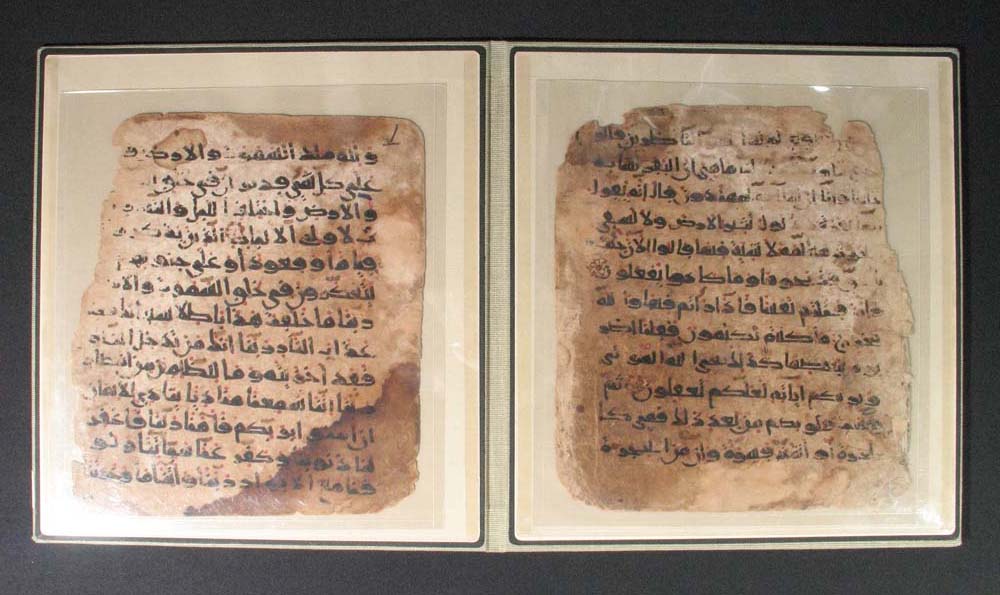

PAPER LEAVES FROM A QUR’ĀN

ca. late 3rd-early 4th c. AH/late 8th – early 9th c. CE

Uncataloged

Two leaves from a Qur’an written in a single column of twelve to thirteen lines in Kufic script, likely produced in Egypt. The word of Allah was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by Gabriel, the messenger of god. The title “Qur’an” derives from a Syriac word for “scripture.” The Qur’an is considered an eternal object, not created in time by any one individual. This copy of the Qur’an illustrates the development of a system of diacritical marks to indicate vocalization. Black dots, placed above or below the letter, distinguish between consonants. The red dots mark short vowels. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

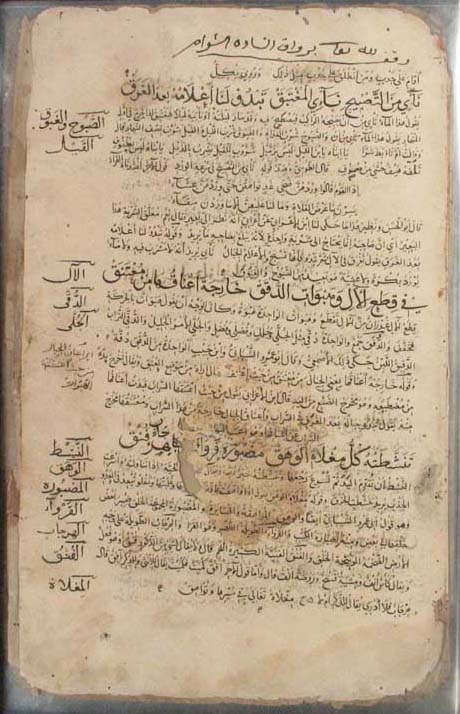

DĪWĀN RU’BAH

3rd c. AH/10th c. CE

Uncataloged

An anthology of diwan (poetry) written on laid paper with several ownership marks. The author, Ru’bah, was an Umayyad poet who died 145/762 in Basra at the beginning of the Abbasid Dynasty. According to the historian ibn ‘Asākir, he wrote a eulogy for the Caliph al-Mansur and met Caliph al-Walid and Suleyman. The poet incorporated Bedouin themes of the desert in this collection of poetry. Rubah was one of several Arabic poets of the time who coined new words or modified others to achieve a certain effect. The poetry is written in a large script interpreted by a gloss in smaller script. The gloss is by Muḥammad ibn Ḥabīb of the School of Baghdad. The author’s name appears on fol. 1r. On fol. 2r, a scribe has copied the lineage of the text, tracing an oral chain of authority, including ‘Abdallah ibn al-A’rabi, ibn Ḥabīb’s teacher and a contemporary of Ru’bah, and ‘Unayf, one of Ru’bah’s rawis. According to this lineage, al-A’rabī stated that the text of the poetry was checked by ’Unayf who himself had checked the text with the poet. In this case, the present manuscript is the third copy made in the life of the poet, who lived in the second century of the Higra years, which fixes the book in the third century AH. A study of the paper corroborates this dating. The manuscript was written by three different scribes, with later hands adding more gloss in the margins. The manuscript has several ownership marks. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. Atiya and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

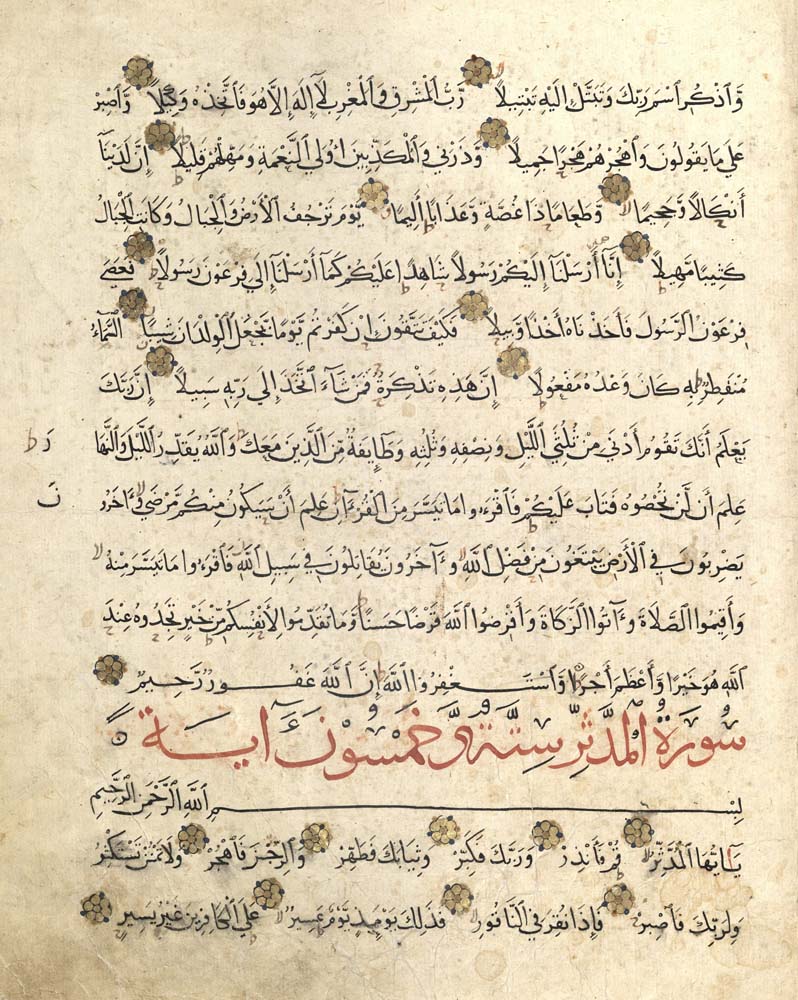

QUR’ĀN LEAF ON LAID PAPER

Egypt, 500AH/1106CE

ND2895 S2 U5 1106

Islamic holy scripture is meant to be recited aloud, either alone or in community. The divine word of God calls for proper recitation. Marks indicate where the reader must pause, may pause voluntarily, or must not pause. The reliance on proper recitation was one method of memorization through oral transmission. The early state of the written Arabic language would have made uniformity of Scripture difficult. The gradual improvement of consistent written Arabic was complete by the late ninth century. Pictorial representation with written Scripture was considered irrelevant to the divine message. The word was all that the devoted needed. However, the development of calligraphy not only transmitted the word of God in written form, but supplied an aesthetic value evocative of Allah’s beauty and power. From the Otto Ege Collection.

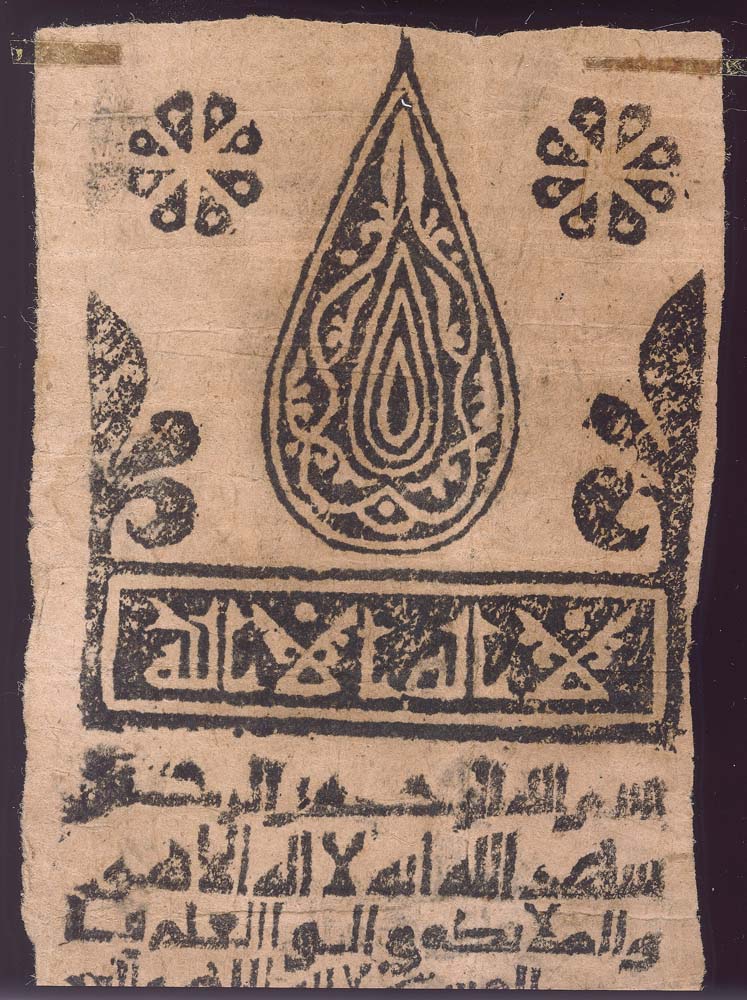

The use of amulets did not originate in Islamic societies, nor was their use unique to Islamic societies. Arabic amulets were largely religious in content. Many amulets from the Arab world contained quotations from the Qur’an. Handwritten talismans served particular individual needs. Printed amulets reflected generic concerns, although the content and function of printed amulets remained virtually the same as handwritten amulets. Both were intended to protect the bearer by thwarting evil forces through the inherent power of the words or names contained in them. Printed amulets were produced to look like handwritten amulets, although they were often more elaborately decorated. Handwritten or printed, the amulets varied a great deal. All, however, relied on supernatural forces such as angels, mystical names, or the holiest name – that of Allah – for their power. The format of the text was fairly standard – a greeting to God, a declaration of intent, invocations, and a closing blessing on the Prophet Muhammad and his family. Despite the fact that amulets were produced with a deliberate aesthetic appeal, they were not designed to be viewed casually, or, for that matter, to be read by mortals. The amulet wearer might be literate or not. The power of an amulet was created by its textual and/or graphic content. The ability to read the text or even understand the graphic symbols was not necessary. In fact, the text was addressed specifically to angels or spirits – the tiny hand or print virtually impossible to read. However, the text was verifiable upon request, much like the active ingredients of medicines are today – meaningless to the layperson, but explicable by an expert. Purchasers believed in the efficacy of amulets in the same way that we take the efficacy of medicine for granted. Similarly, amulets were produced with the same degree of certainty about the value of the product. The amulets were folded tightly, sometimes before the ink was dry, and remained folded. Most were put into ampules and then attached to garments or worn around the neck. Block-printed amulets disappeared due to economic competition. They did not fetch high prices and the buying power of the populace was limited. There were limits to the ways in which block-printed amulets could be personalized. Custom-made handwritten amulets had more appeal in a competitive marketplace. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

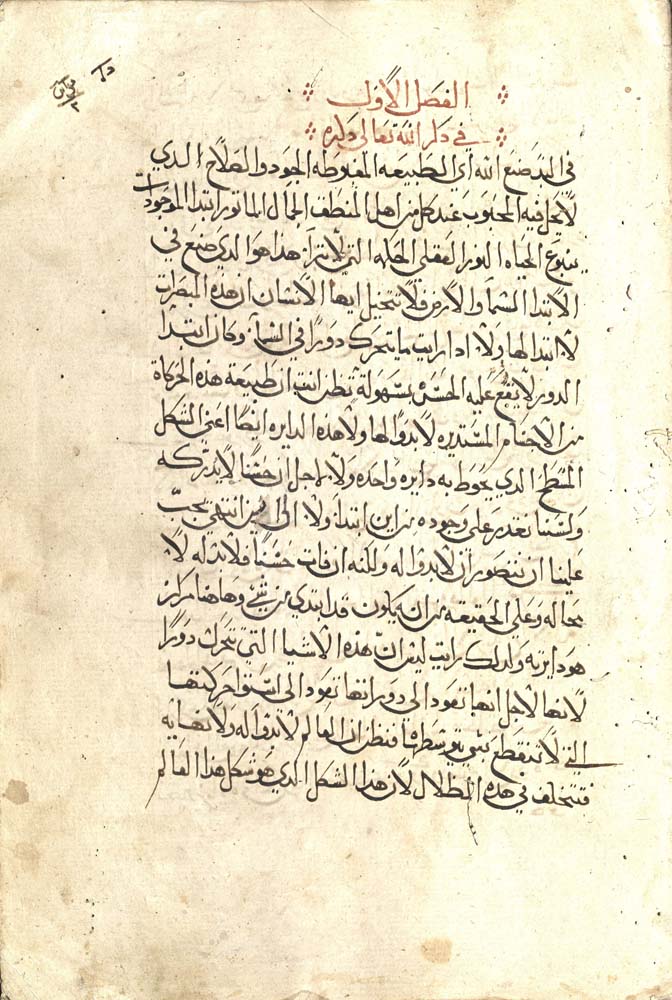

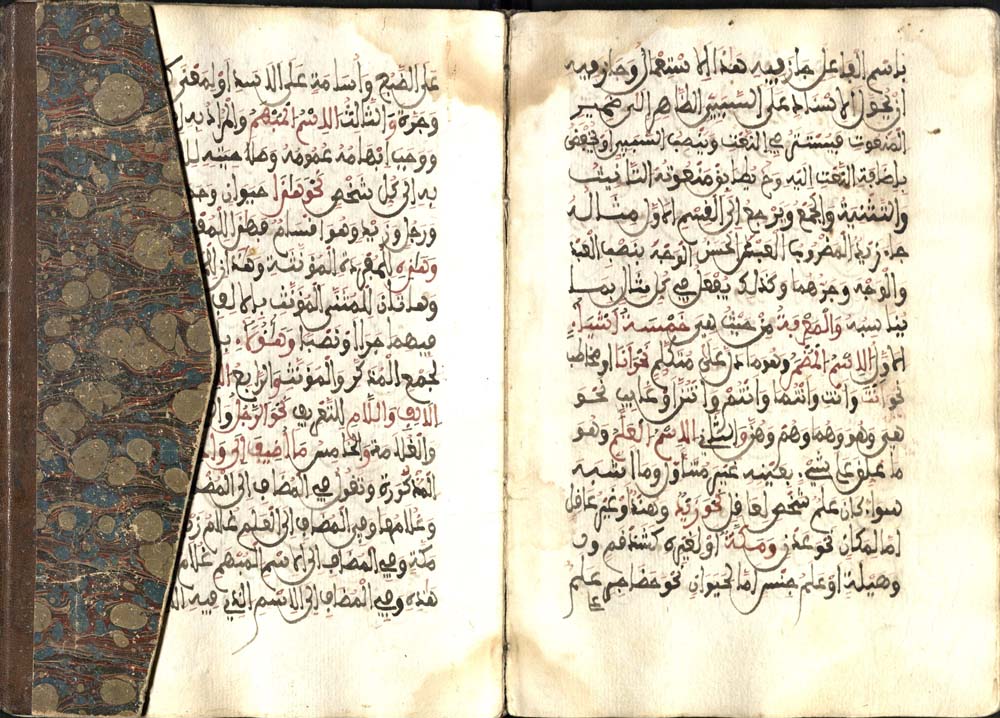

COMMENTARIES

9th c. AH/15th c. CE

Uncataloged

This manuscript, written on polished laid paper, is an Arabic translation from a Greek or Coptic original of writings by St. Basil the Great and St. Gregory of Nyssa. It is written in large naskh script and contains an illumination of the Coptic Cross, surrounded by birds between the texts of the two books of commentary. Beginning sections of text are marked with red ink for the text, framed by diamond-shaped lozenges in red and black. Although the manuscript is undated, the motifs and painting style are typical of Egyptian illumination of the early 9th c. AH/15thc. CE. St. Basil the Great was born in Caesarea, the metropolis of Cappadocia. After he attended school in Constantinople and at Athens he opened an oratory and law practice. Soon afterwards, he established a monastery in Pontus, which he directed for five years. He wrote a monastic rule which would become the longest lasting of those in the Byzantine East, still practiced by monks of the Eastern Orthodox church. St. Basil was one of the giants of the early church. He was responsible for the victory of Nicene orthodoxy over Arianism (which denied the divinity of Christ) and the denunciation of Arianism at the Council of Constantinople in 381/82. St. Basil’s brother, Gregory became a Christian in his early twenties. Married, he went on to study for the priesthood. He was elected Bishop of Nyssa (in Lower Armenia) in 372. Gift of Dr. Aziz and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

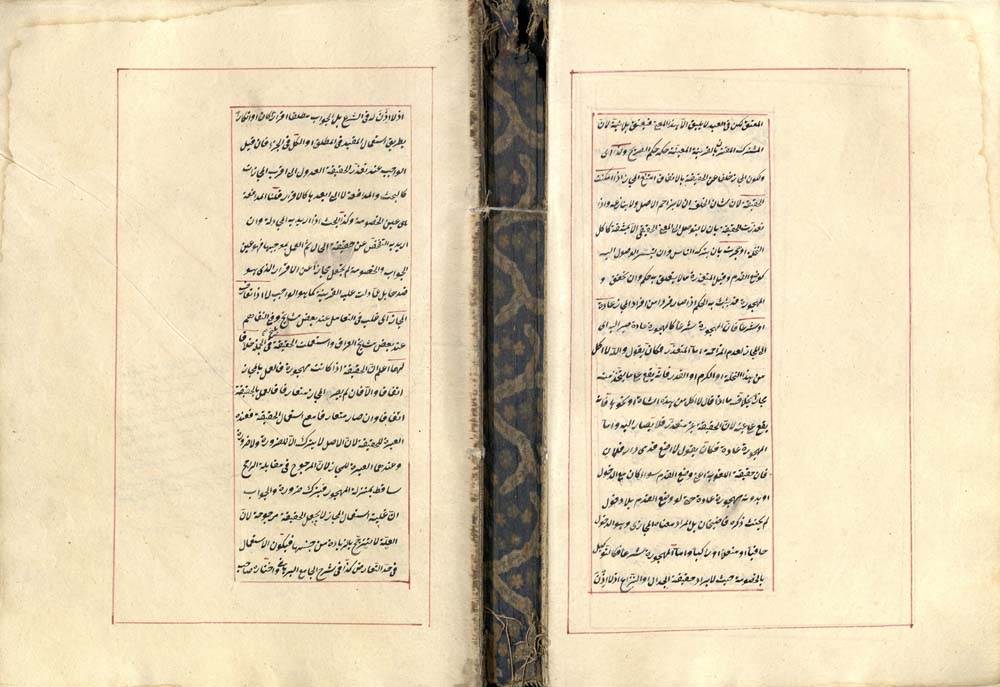

A commentary by Molla Husrev, “Mirror of principles…” on his own work, “Stairway for reaching the sciences of the principles of jurisprudence.” Molla Husrev was a jurist of the Ottoman Empire. He first taught in Adrianople, followed by a position in 848/1444 in Istanbul. He moved to Basra in 867/1462 to establish his own theological school, but returned to Istanbul, accepting the position of Sheik-al-Islam, a judicial authority presiding over a religious tribunal. Molla Husrev followed the teachings of Abu Hanifa, who emphasized human reason in theoretical law. Islamic law is based on an understanding of the will of Allah, as revealed in the maxims (hadith) of the Prophet Muhammad. This manuscript, produced in Turkey, was copied in Ta’liq script on slightly burnished laid paper and has seventeen lines per page. A partial table of contents fills folios 1b-2a. A double border in red runs throughout the first quire. The text is highly glossed in one hand, with several marginal notes erased. Bound with marbled paper glued to pasteboard covered in thin vellum. Gift of Dr. Aziz and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

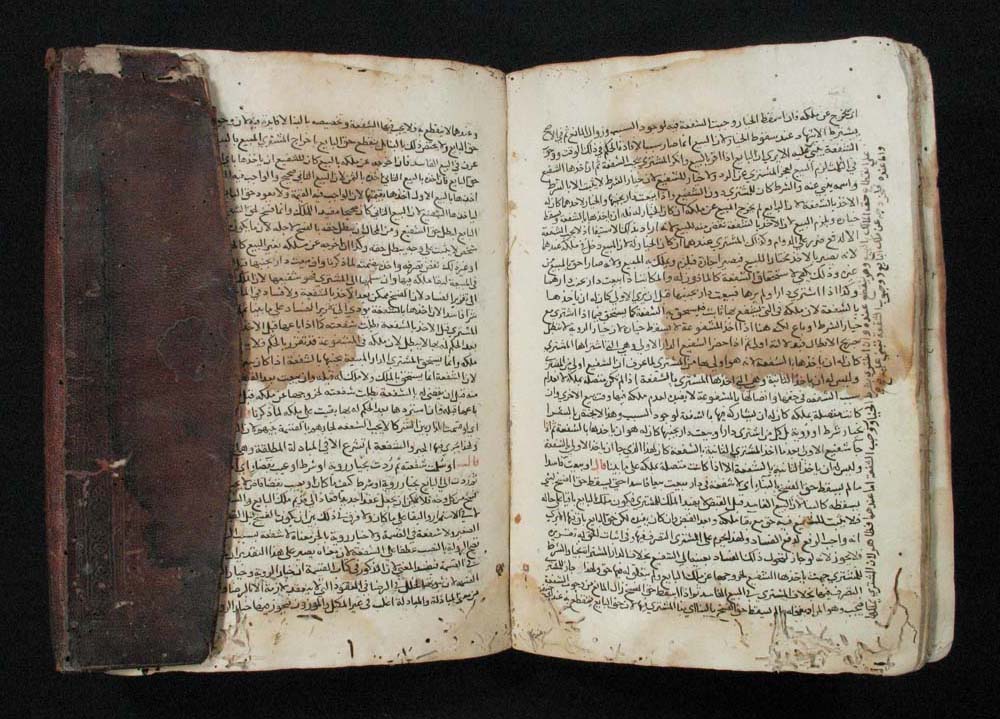

AL-JUZ’ AL-RĀBI’ MIN SHARḤ AL-KANZ

902 AH/1496 CE

Ms Or. 11.5

The fourth and last part only of al-Zayla’ī’s controversial commentary on al-Nasafi’s Kanz, a work on Islamic law, on ‘anafi fiqh. Script is old but clear naskhi; diacritical dots present (with some added at a later time); rubrications; marginal notes and corrections; occasional verses and rustic basmalah on last folio; laid paper; wormholes; water-stains throughout. The binding boards are stuffed with scraps from other manuscripts. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

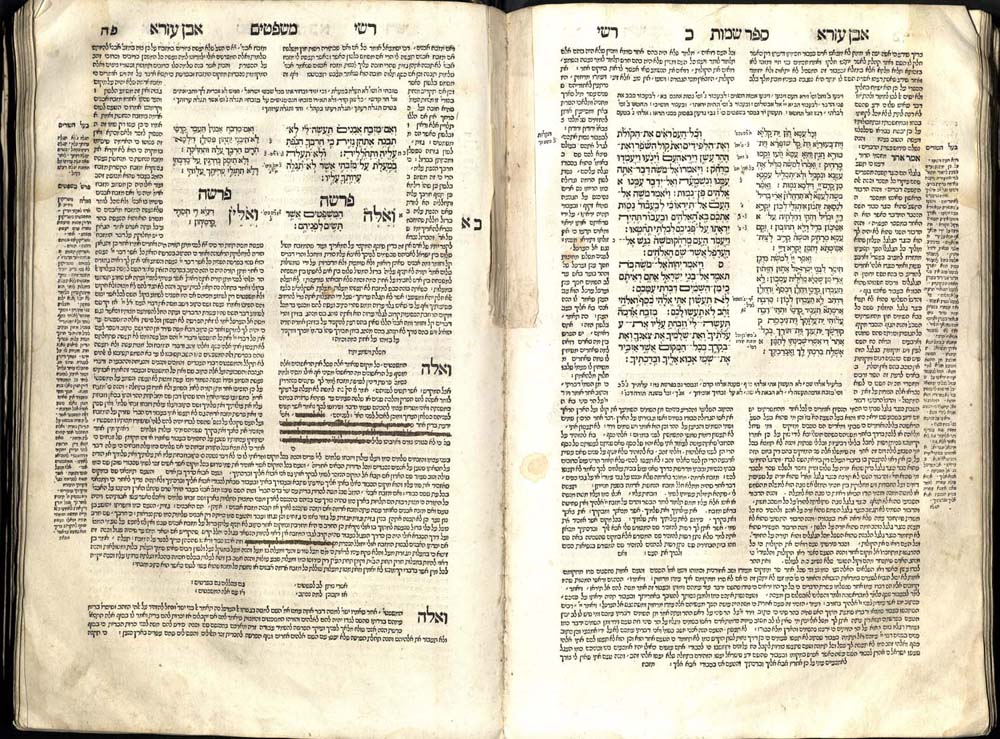

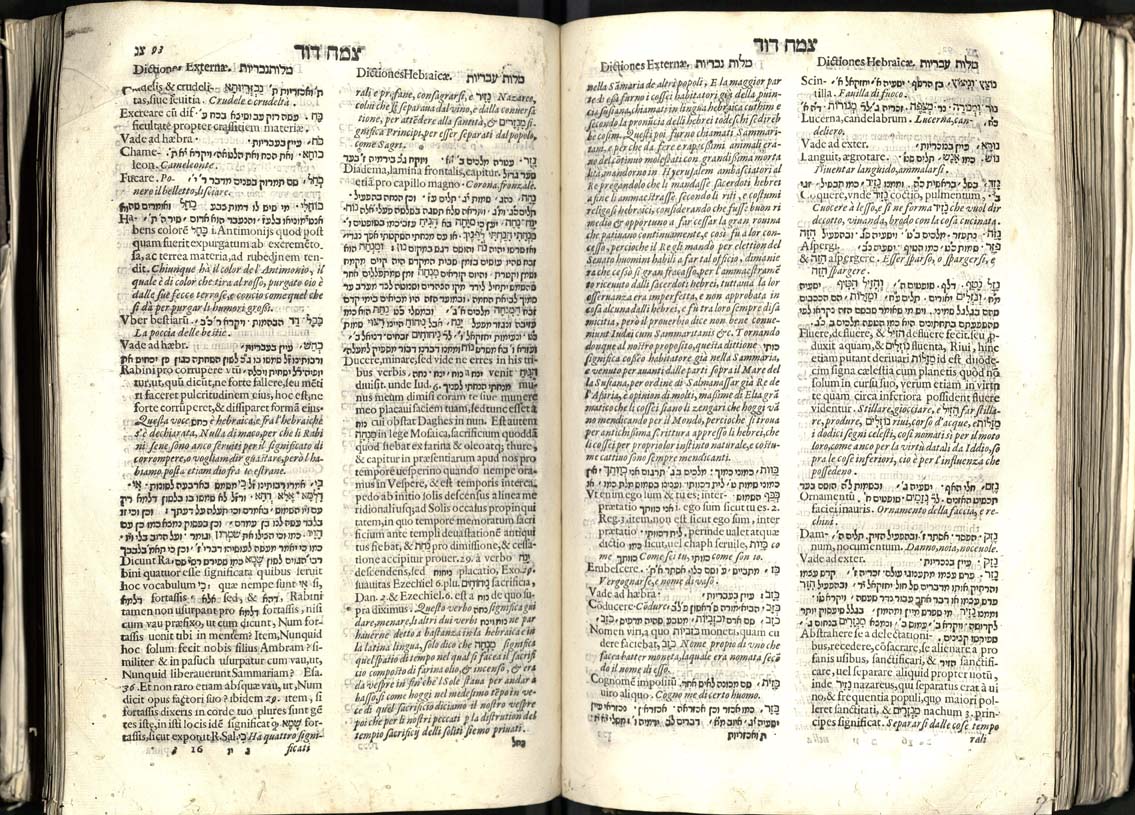

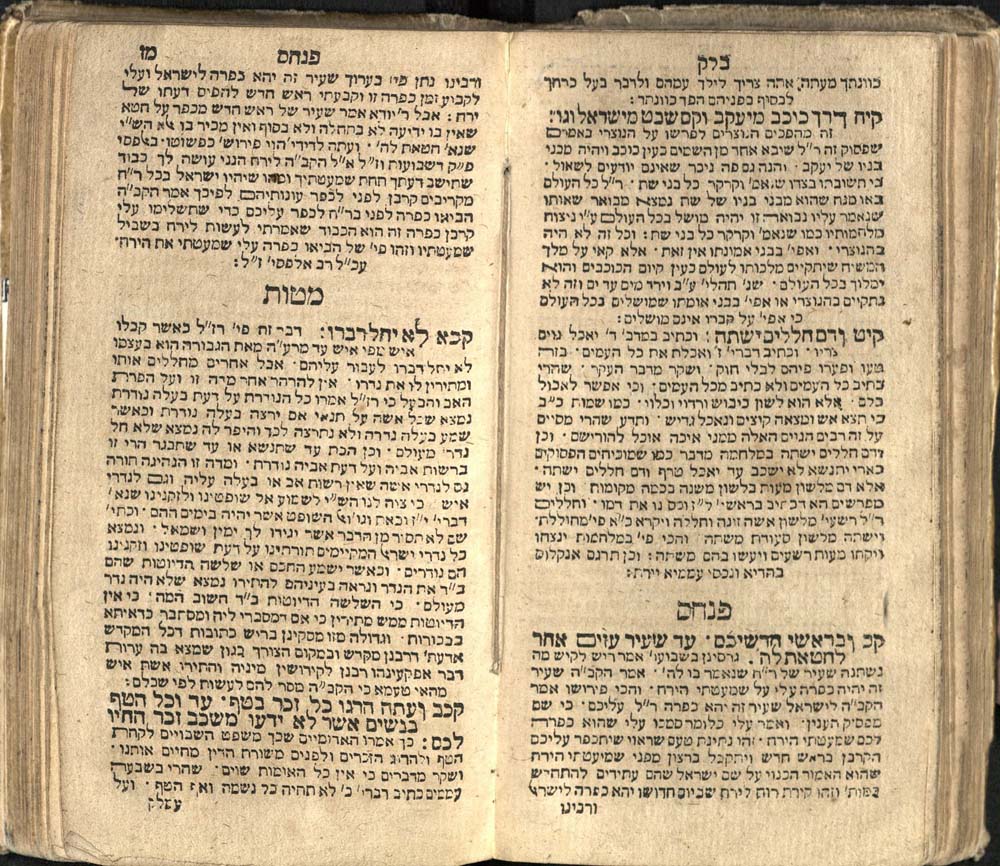

ARBA’ ṾE-‘EŚRIM…:HA-ḤUMASH ‘IM TARGUM U-FERUSH RASHI ṾE-IBN EZRA U-FARPERA’OT MI-BA’AL HA-ṬURIM: ṾEHA-NEVI’IM HA-RISHONIM ‘IM PERUSH RASHI ṾE-ḲAM’I ṾE-RALBAG ṾE-RABI YESHAYAH: U-NEVI’IM HA-AḤARONIM ‘IM PE’ RASHI ṾE-ḲAM’I: ṾEHA-KATUVIM…VEHA-MIḲRA’OT METURGAMIM…

Venice: Daniel Bomberg, 1547-49

Third edition

BS715 1547

Daniel Bomberg was one of the earliest Christian printers of Hebrew books. Bomberg operated a press in Venice, investing 4 million gold ducats into his printing house. In 1516, Bomberg printed his first edition of the Rabbinic Bible. At a time when there was a growing interest in the Hebrew language and the Old Testament among Christian scholars, Bomberg also recognized a market for Hebrew texts among Jews in Italy as the population grew with an influx of Spanish and Portuguese Jewish exiles. Bomberg’s publications provided the basis for the revival of western Semitic scholarship and studies both in Hebrew and Arabic. Bomberg printed more than two hundred books in Hebrew, known for their outstanding scholasticism, beautiful paper, and typographical excellence. Bomberg’s placement of commentary surrounding the text (a popular early printing style based upon manuscript glosses) in his editions of the Bible influenced the appearance of many other types of Jewish literature. The commentary in Bomberg’s Biblia Rabbinica appears to swallow the biblical text. Bomberg’s Bible was accompanied by commentaries by some of the best Jewish and Christian scholars, including Rashi, ibn Ezra and ben Asher. Bomberg made use of as many manuscripts of the Old Testament as possible, and influenced many of the Old Testament translations by Reformation-era Biblical scholars. This copy contains several instances of Italian censure, where pens were used to strike out lines of commentary considered blasphemous, and the signatures of those censors. Each censor found different passages by the commentators that did not agree with then-accepted New Testament theology. The University of Utah copy was part of a large private collection owned for centuries by one family. Parts of the collection were scattered across Europe after the family fled from Spain. This Bible, however, remained in the family and was brought to Utah from Latvia when family members migrated in 1935. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Alder.

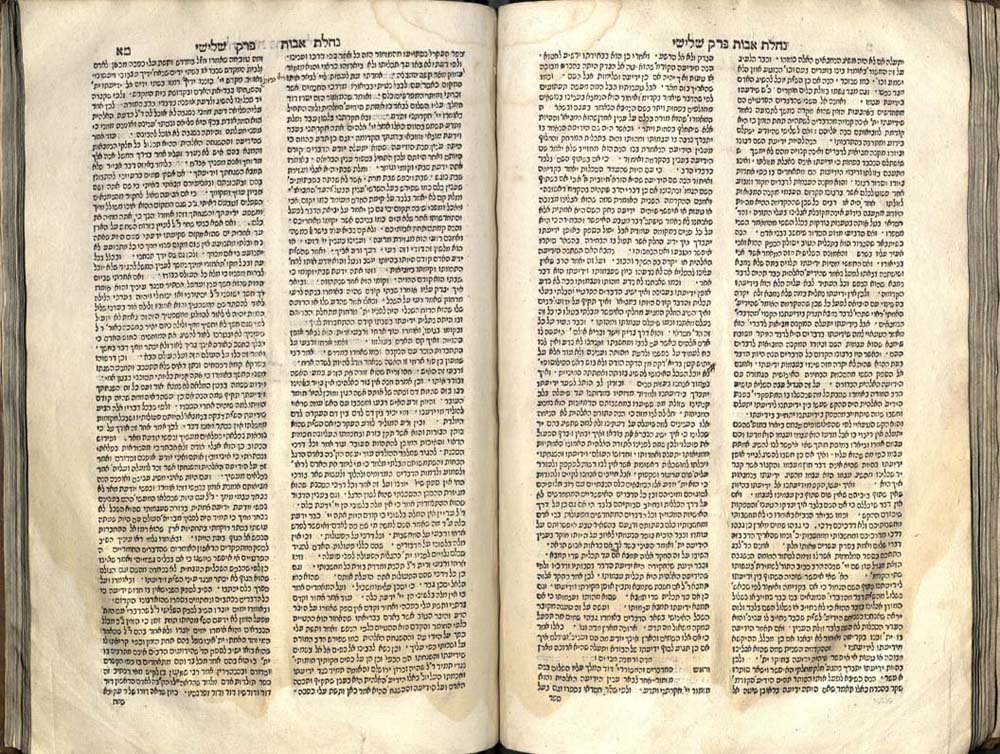

Compiled by R. Yehudah Hanassi at the turn of the 2nd/3rd centuries, Pirke‘ Avot, a section of the Mishnah, is a series of moral maxims covering civil and criminal rabbinical law, some of which appear to be targeted toward judges in the way they conducted trials. It was commented on by Don Isaac Abravanel. With these commentaries, it has been printed more than any other Talmudic work and is included in editions of the traditional prayer book. Because it furnishes teachings of what Jewish sages considered fundamental aspects of life and because the teachings were expressed in neat epigrams, Pirke 'Avot became the best known Talmudic treatise among non-Jews. It was translated into Latin as early as 1541, and then into English, French, German and Italian. Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) was born in Lisbon. He was the treasurer to King Alfonso V. He was suspected of being in league with the Duke of Braganca against Afonso’s successor, Joao II, and fled Portugal for Italy in 1483, where he spent the rest of his life. Pirke‘ Avot was first printed in Naples in 1492. This second edition was printed in Venice by Giorgio de Cavalli, a Christian printer who, along with others, picked up the work of Daniel Bamberg after his death. Cavalli employed both Christian and Jewish typesetters, helping to assure the quality of his Hebrew printing.

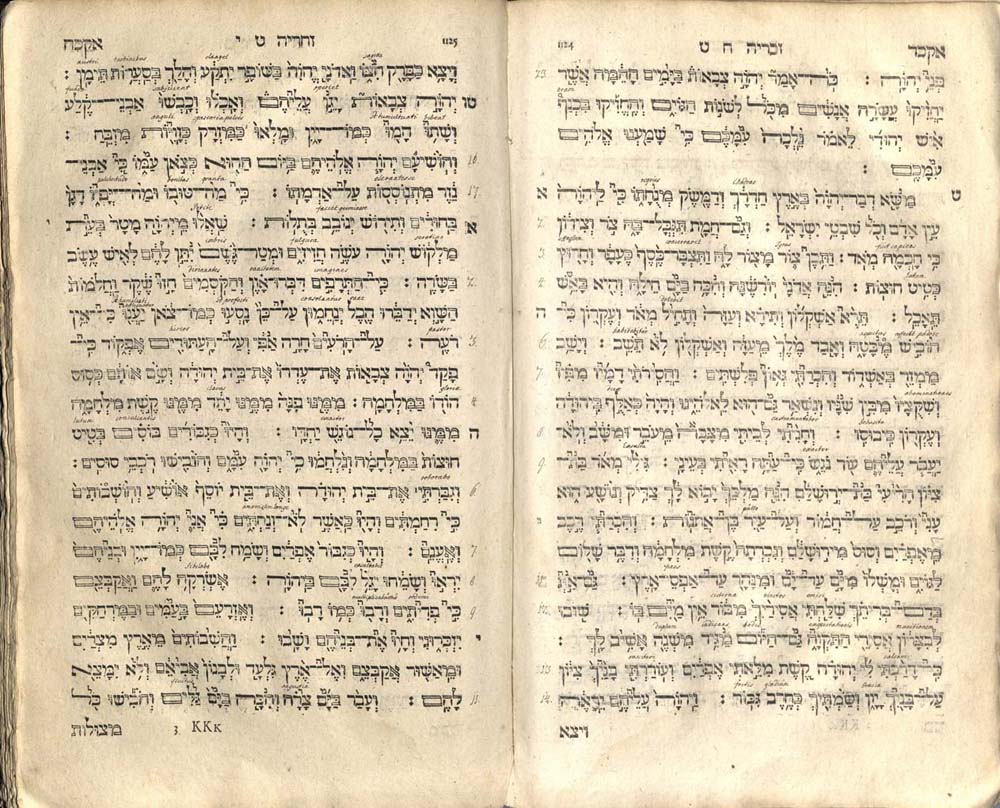

Hamburg: Impressa typis Elianis, per Johannem Saxonem, 1587

First edition

BS715 1587

Elias Hutter (ca. 1553- 1609) was born in Ulm. A Protestant, he studied Oriental languages and became a professor of Hebrew at Leipzig in 1577. He was a renowned editor, publishing a series of polyglot editions of the Bible as well as editions of the Hebrew Bible. He is best known for this Hamburg 1587 edition. His main objective in producing a Hebrew Bible was one of practicality – to make the Hebrew Bible more accessible to the student of Hebrew. His edition used two forms of type – large fonts of a solid, thick, heavily inked letters for roots and a hollowed-out font for prefixes and suffixes. This typographical educational tool enabled the student to recognize the root of any Hebrew word. Quiescent letters in a smaller font size were printed above the line, thus exhibiting the radix of every word. This gave the reader a better understanding of the literal meaning of the Bible. Although Hutter was not particularly concerned with the aesthetic quality of the typography, he produced a distinguished-looking book. Hutter was concerned with scholastic accuracy and tried to provide his readers with a text as close as possible to the original. He consulted the oldest ancient manuscripts he could find. Unfortunately, he work was not particularly commercially successful. The various Hamburg firms that printed the works of Elias Hutter all had difficulties meeting their financial obligation or had difficulty selling off old stock. The Hamburg firms would resort to a variety of repackaging/reissuing schemes to clear their shelves of old Hutter Bibles and other works. The University of Utah copy is bound with Hutter’s Cubus alphabeticus sanctae Ebraeae linguae, printed in Hamburg in 1588 by Jacobus Wolfius.

David de Pomis was a linguist, physician, philosopher and rabbi. He worked as a physician near Rome until Pope Paul IV’s edict in 1555 forbidding Jewish physicians to treat Christians. Four years later he settled in Venice, where he published most of his works. Pope Pius IV gave him permission to attend to Christians, a concession revoked by Pius V and then restored by Sixtus V. De Pomis dedicated this trilingual Hebrew, Latin, and Italian dictionary to Pope Sixtus V. The introduction includes the author’s autobiography and a genealogy. The text is indexed.

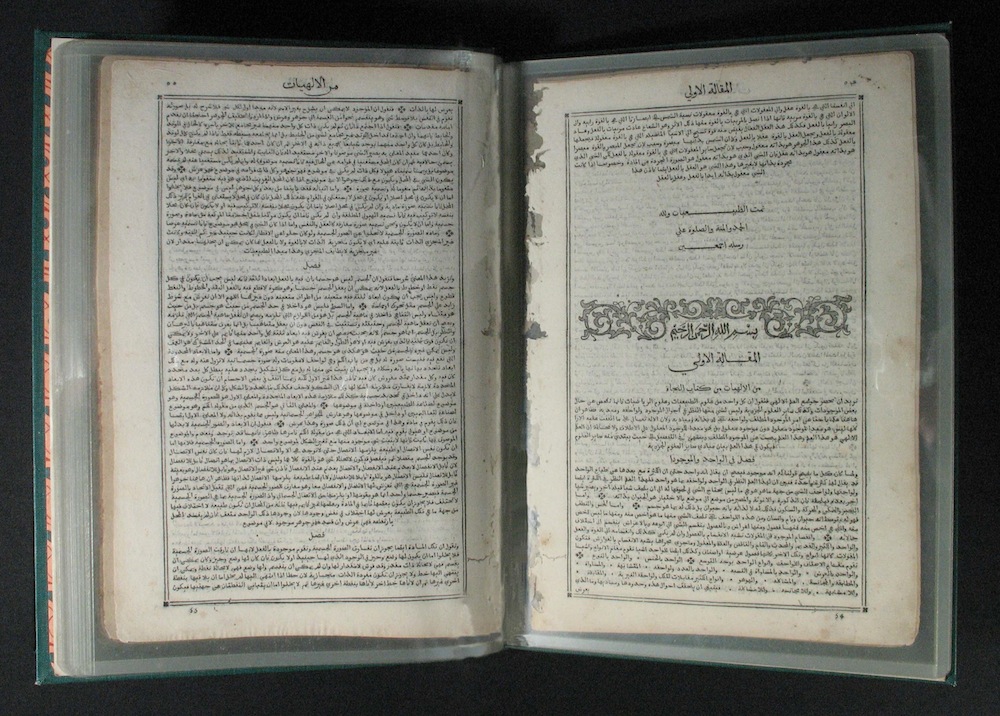

KITĀB AL-NAJAH

Rome: Medici Printing Press, 1593

B751 N3 1593

Avicenna (Ibn Sina) was the most illustrious philosopher, scientist, and medical writer of medieval Islam. He introduced the works of Aristotle to the Arabs. His two most important books, Al-Shifa (Healing of the Soul) and the Canon of Medicine were extremely influential in the development of philosophy and medicine in the East, and, through Latin translation, in the West. Al-Shifa is an encyclopedic work divided into four principal parts: logic, physics, mathematics, and metaphysics. The selections here were printed in Rome by the famous Medici Press, which used the first Arabic type in the world.

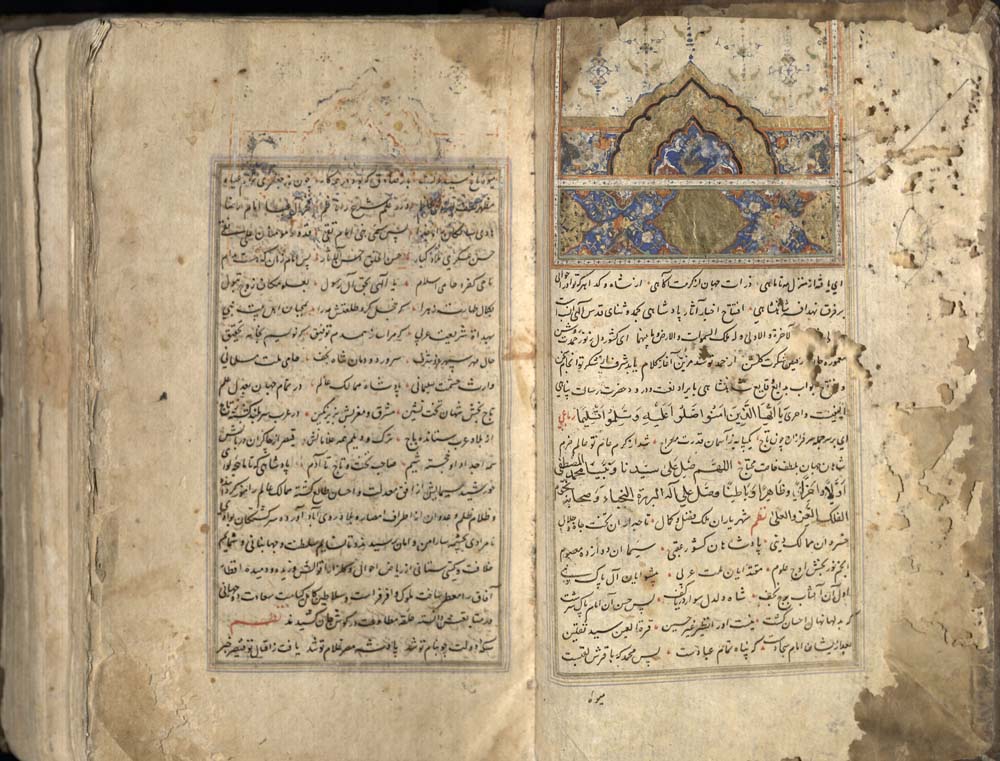

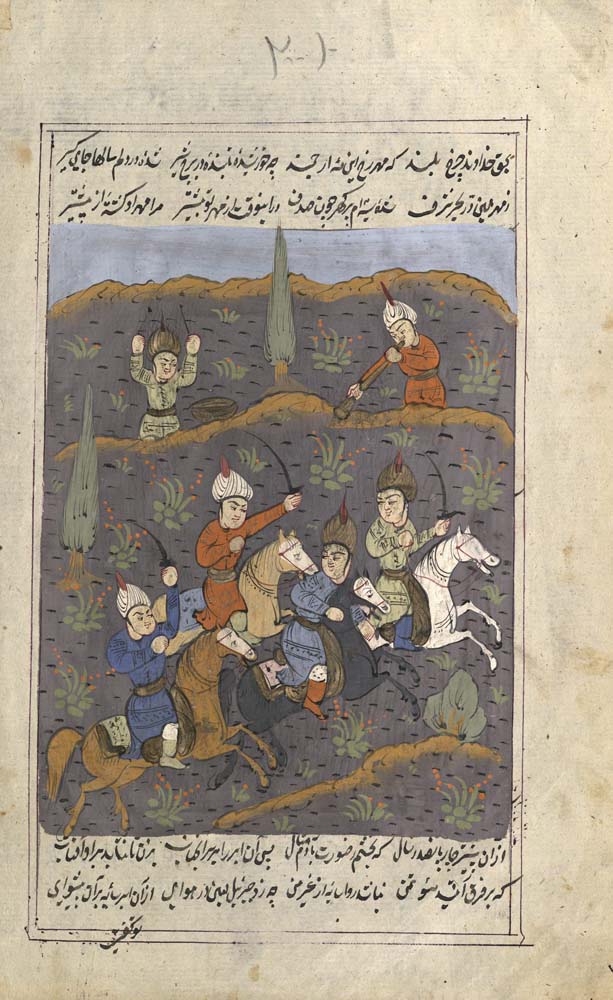

ḤABĪB AL-SIYAR FI AKHBĀR AFRĀD AL-BASHAR

1007 AH (4 Muharram)/1598 CE

DS289.7 K485 1598

This volume is part 3 of volume 3 of Khwānd Mīr’s general Persian history from the earliest times to the end of the life of the Safavid King Isma ‘il, extending to 1524, eleven years before his death. The three volumes were each subdivided into 4 juz, or parts. Part 3 of volume 3 is on Timur and his descendants to Sultan Husayn’s sons (1369-1469). The scribe, Mirza Ali Muzaffar Katib, worked in a nasta ‘liq hand. Binding is brown leather with large central and corner medallions. Paper is laid, with illuminated title page, and gold bordered text.

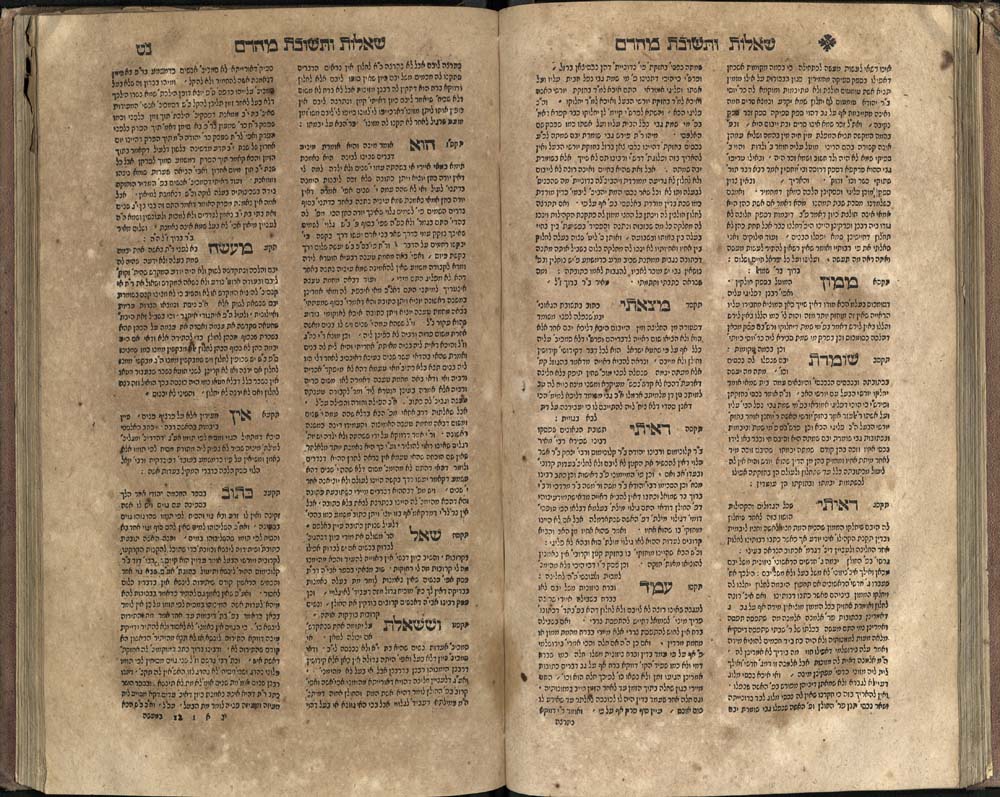

Meir ben Baruch was born in Worms, Germany. He studied in Mainz with the leading Talmudists of his day. He moved to France and studied further with Rabbi Yechiel ben Joseph of Paris, who defended the Talmud during the reign of Louis IX. There, Meir witnessed the public burning of twenty-four cartloads of Talmudic manuscripts on Friday, June 17, 1244. Returning to Germany, he opened his own school. He became known as the leading Ashkenazi authority on Talmud and Jewish law. In 1286, Rudolf I instituted new laws against the Jews, declaring them servi camerae (“serfs of the treasury”), which negated much of their political freedom. Meir, with many others, left Germany but was captured in Lombardy and imprisoned in Alsace. He died there seven years later. Rabbi Meir is best known for his responsa, which today give a picture of the condition of thirteenth century German Jews – their life and customs, and their sufferings from heavy taxation. His work greatly influenced the work of codifiers in subsequent centuries and helped standardize Jewish legal procedure and civil law. This volume of his responsa was first printed in 1557. Leaves 3 and 4 of this edition were destroyed during printing. The University of Utah copy is one of only two copies listed in libraries throughout the world. Gift of Judaica Associates.

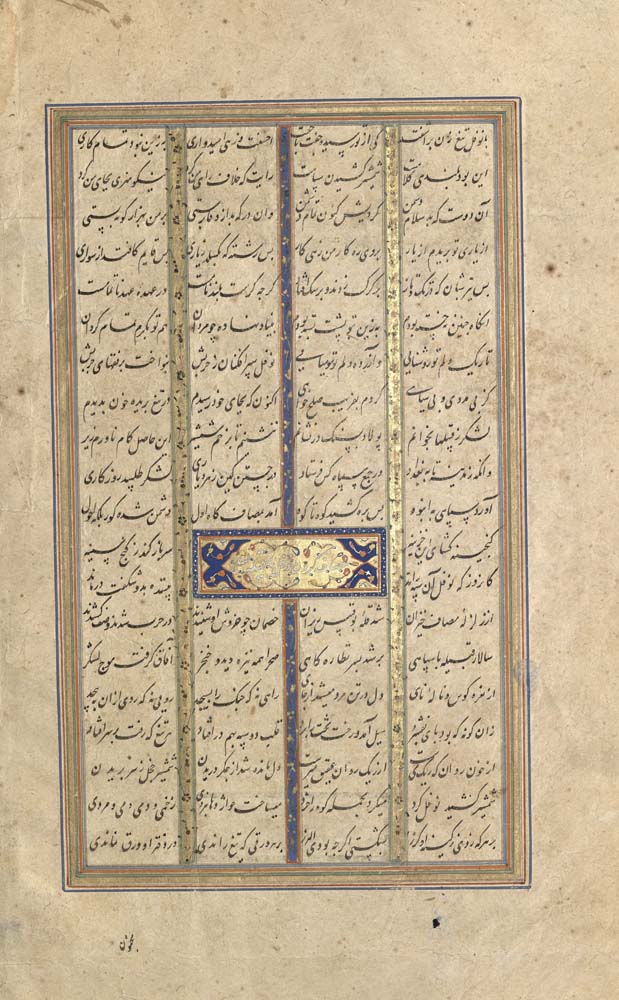

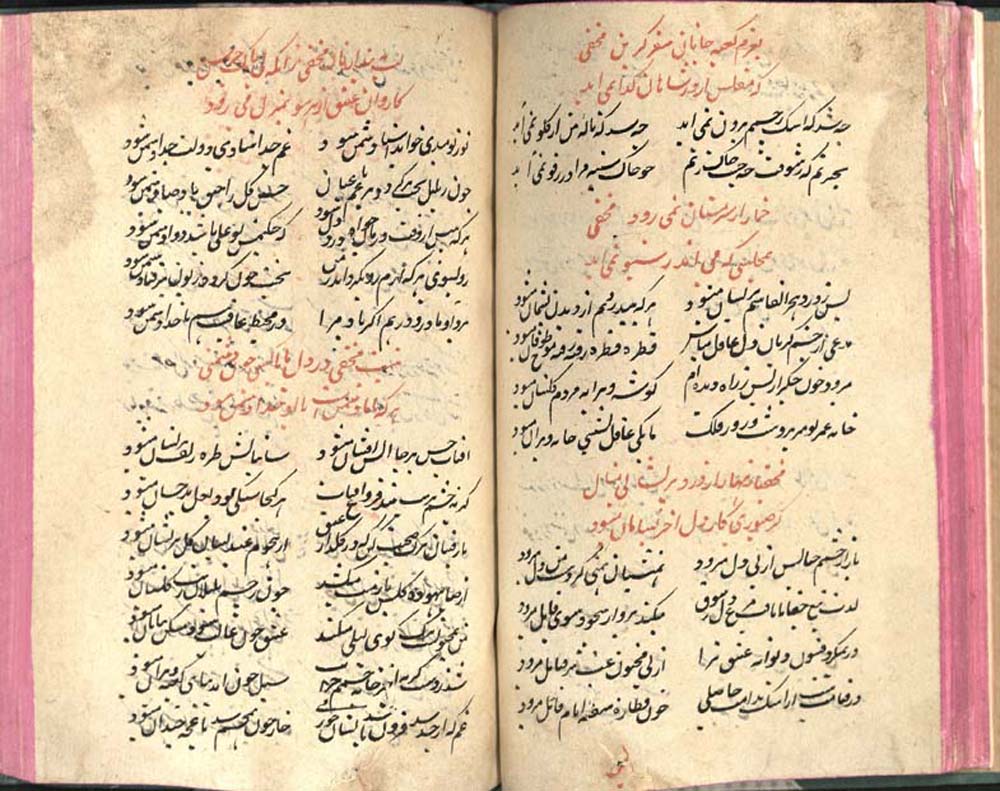

LAILI U MAJNUN

Iran?, 1625

ND2895 S2 U5 1106

This famous medieval Persian romance in verse tells the story of a school- boy infatuation that becomes a lifelong, unrequited passion. Thwarted by the disapproval of his parents, the boy, Qays, loses his mind, earning him the nickname “al-Majnun” (madman). Majnun and his love Layla never unite in life, but were buried in a single grave. Tradition says that the story is based upon real persons. Some of the verses are alleged to have been written by Majnun himself. The poet Nizami was born at the end of the Umayyad period and studied traditional epic poetry, which incorporated love lyrics or ghazal. Nizami became one of its greatest proponents. Nizami completed his Laili u Majnun in 1188, his lyrics reflecting his Sufi faith. Nizami wrote for a small circle of sophisticated, highly educated readers at Persian court. He dedicated his poem to his patron Shirwanshah Acksitan Minuchihr, a Transcaucasian chieftan. Illumination on polished laid paper, coated with gold powder suspended in a liquid to give it sheen. The page layout is of four columns, each separated by a strip of blue pigment on which are painted blossoms in liquid gold and long, thin stylized leaves.

This small codex from the early Ottoman period was calligraphed on polished laid paper in naskh script. The title page is illuminated with a lozenge in gold and azure with polychrome flowers. All the pages are framed in gold. Several folios throughout are dyed red on one side. Corrections and additional markings are in red ink. The leather binding is embossed in the center and corners. The embossing is filled in with a layer of gold leaf. The end papers are decorated with ebru, a technique of marbling paper developed in the Ottoman Empire at the end of the fifteenth century. This manuscript contains the ownership marks of Ismai’il Ḥaqqi, dated [1]063 (1652); Muḥammad ibn Muṣṭafa, dated [1]108 (1696); and Muḥammad ‘Aṭā’ Allah, dated [1]094 (1780). The text is on Islamic jurisprudence, al-Maḥbūbī’s Tawdīh, a commentary on his own Tanquih’al-usul. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. Atiya and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

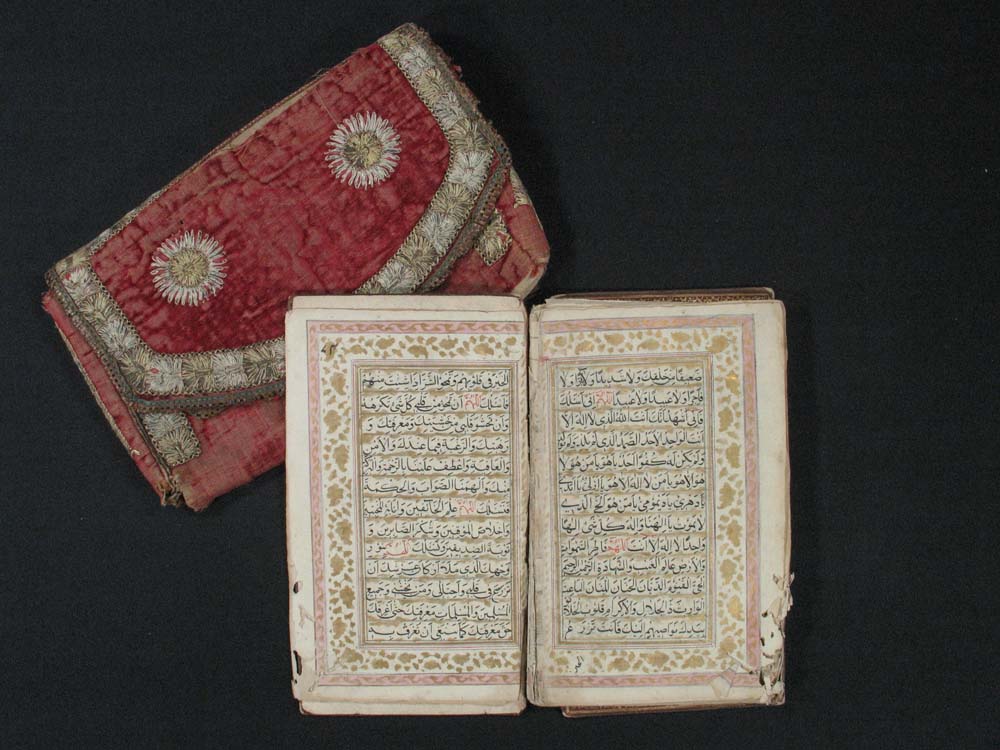

Late 17th century

BP188.2 J39 1600z

Undated manuscript of Munajat, a popular devotional work. Naskh script within gold rules and hashiya, illuminated with two double-page Sarloughs and other decorations. Titles ornamented in blue and gold floral designs, text pages bordered with pink and gold, two pages of rare pictorial designs. The illustrations are of “al-raw’ah al-mubarakah allati dufine fiha Rasul Allah” – the blessed courtyard where the Prophet of God is buried. Binding is leather with gilt housed in an embroidered red velvet case. From the Kenneth Lieurance Ott Collection donated to the Okanogan County Museum, Washington.

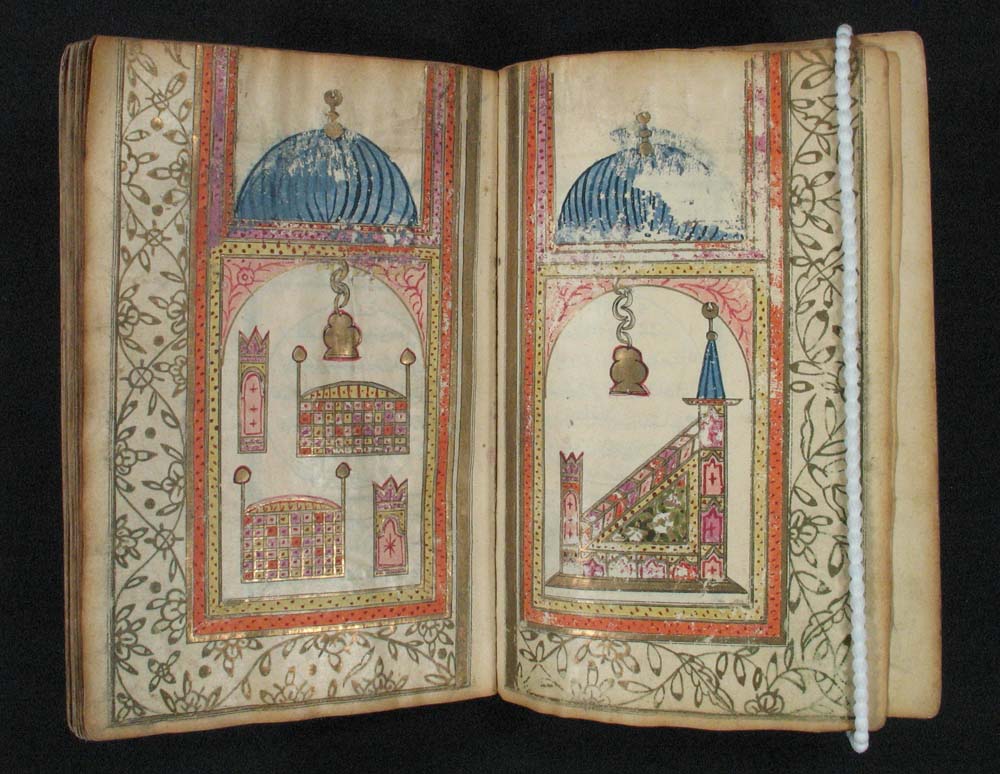

This small devotional of Munajat is written in small calligraphic naskh with rubrications on laid paper. Polychromatic illuminated opening with floral border in gold; borders in gold throughout; text is contained in circles held between two rectangles. Several of the circle backgrounds are filled with green. Polychrome illuminations of the mosques at Mecca and Medina. Bound in leather tooled with gold medallions and corner decorations. Gift of Dr. Aziz S. and Mrs. Lola Atiya.

This collection of poetry, written by Zīb al-Nisā Begam (1638-1702), the daughter of Awrangzib (1618-1707), the last major Mughal Emperor of India, is written in a nasta ‘liq script on laid paper with endsheets watermarked with a crowned shield with bird and tower. The text is written in double columns with headings in red across both columns. Overlining, synonyms and decorative elements are in red. The late rebinding destroyed some of the commentary. As a member of the royal family, Zib al-Nisa studied Persian, Arabic, Dari, Hindi, calligraphy, mathematics, and astronomy. By the age of seven, she had memorized the Qu’ran. As a young woman, she held considerable influence over her father’s political thinking, often helping him settle disputes between Sunni and Shia. She held her own courts at Delhi and Lahore, which became meeting places for scholars and poets. She established a library and employed calligraphers to copy classical Arabic texts translated into Persian. She established a scriptorium in Kashmir, noted for its excellent paper and scribes. She began writing poetry when she was fourteen. Zib al-Nisa chose the Sufi path over that of her strict Muslim father. In 1681 her younger brother unsuccessfully rebelled against her father. Zib al-Nisa was accused of allying herself with the rebellion and was imprisoned. From that time, there is no record of her until her death in 1702. She was able to circulate her poetry as “Makhfi,” or, “the hidden one.” Thirty-five years after her death more than four hundred of her poems were collected and translated into Persian as Diwan-i Makhfi. Many of her poems are ghazal, an Arabic form. Zib al-Nisa’s poems are expressions of her Sufi belief and her personal devotion to Allah.

Commentary on Ibn Ajurrum’s al-Ajurrumīyah, an Arabic grammar. Ibn Ajurrum (672/1273-723/1323) was from a Berber family. He died in Fez. He was a teacher of grammar and Qu’ran recitation. He is best known for this text, in which his method of teaching Arabic grammar incorporates general rules with examples. It is said that after finishing this text, ibn Ajurrum (d. 1327 CE) threw his copy into the sea, saying, “If this was purely for the sake of Allah Most High, it will not get wet.” And, it did not. Study of this book spread from Syria to Morocco. It is a text still used today. The text was first translated into Latin in 1592. This copy is written in Maghribi script with vowelled/rubricated text. Laid paper with a three graduated crescents watermark. Bound in leather with flap, covered in marbled paper.

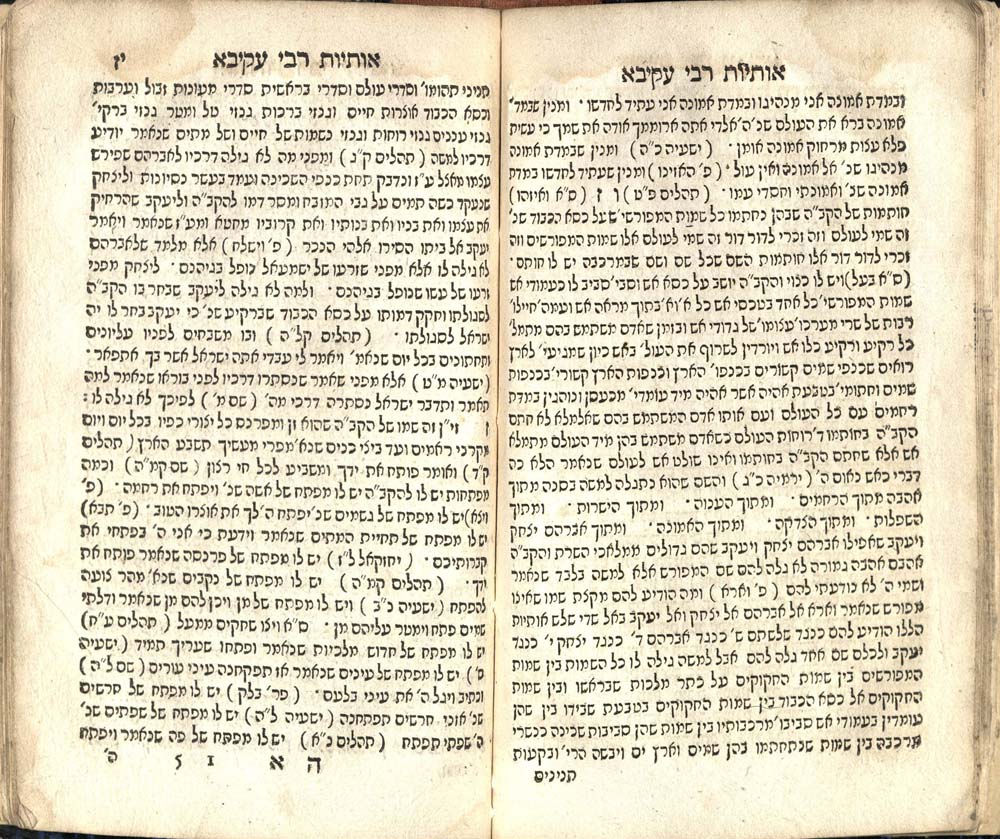

Rabbi Akiva (ca. 50-ca.135), an authority on Jewish tradition, contributed to and compiled the Mishnaic literature of the Talmud. He was well-known as a great mystic. Dutch scholars Jacob Alvodish Suto, Moses Ibn Yakov Brandon, and Benjamin DiJunk published their commentaries on Akiva’s famous discourse on the Kabala in Amsterdam in 1708. Akiva discussed the mystical potency of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet through which, according to Kabalistic tradition, God created the world. Akiva’s discourse is in two parts. In the first, the letters of the alphabet compete before God, each claiming their virtues to be chosen as the letter through which God begins the Torah. In the second, Akiva demonstrates how various words in Hebrew can be decoded by viewing them as acronyms comprised of the beginning letters of words which make up entire sentences. Akiva’s discourse is based upon ancient writings and Talmudic sources.

Compiled in 1390 by the great rabbinic authority of medieval Prague, Yom Tov Lipmann Muelhausen, the widely-read Book of Victory was so controversial that it wasn’t printed until the seventeenth century. Christian Hebraists reviled its response to their religion. So polemical was the text that it was actively hidden from Christian readers. It remained, however, the main recourse for those in need of arguments to refute the interpretation of Hebrew Scriptures used by those who sought the conversion of the Jews. The book was first printed in the seventeenth century – once in full, edited by T. Hackspan, Altdorf, 1644, and once in part, edited by J.C. Wagenseil, Altdorf, 1681 – in both cases, ironically, by Christians with a counter-counter-missionary agenda. This edition is the first printing of Nitsahon by and for Jews, printed in Amsterdam at the height of that city’s reputation as an exemplary haven of free speech. Gift of Hebraica Fund.

HEBREW SCROLL

bef. 1772

Uncataloged

Text is the Book of Esther. This scroll was purchased in a small shop in Barcelona, Spain. It is estimated to date from the mid-to-late eighteenth century. Gift of Mr. Ben M. Roe.

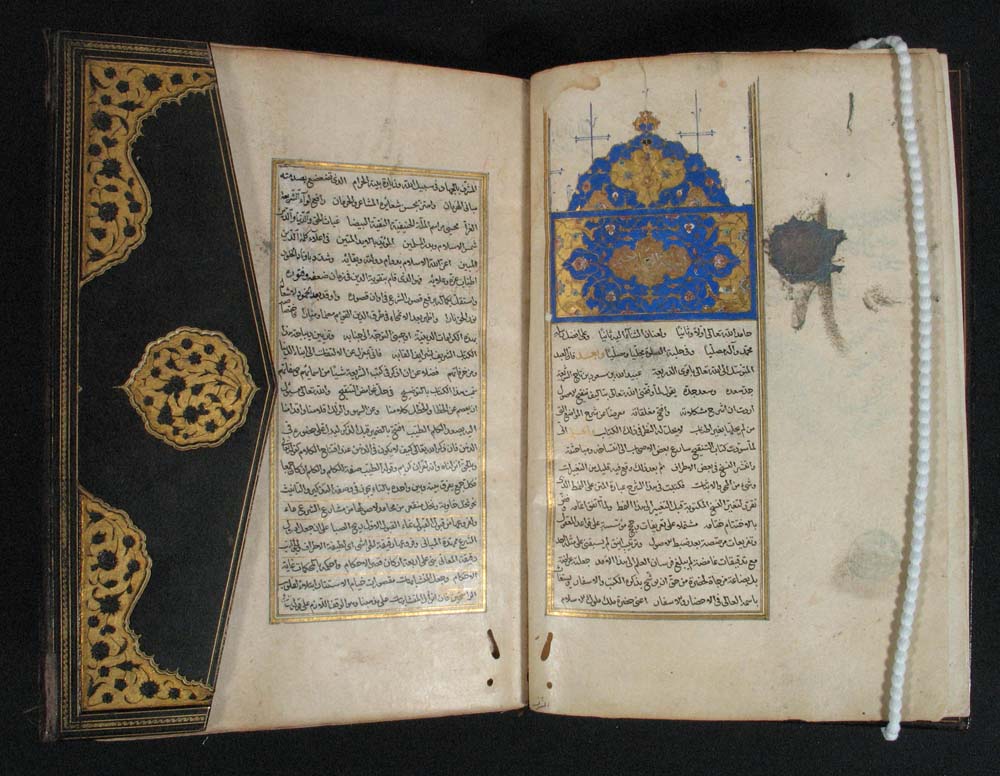

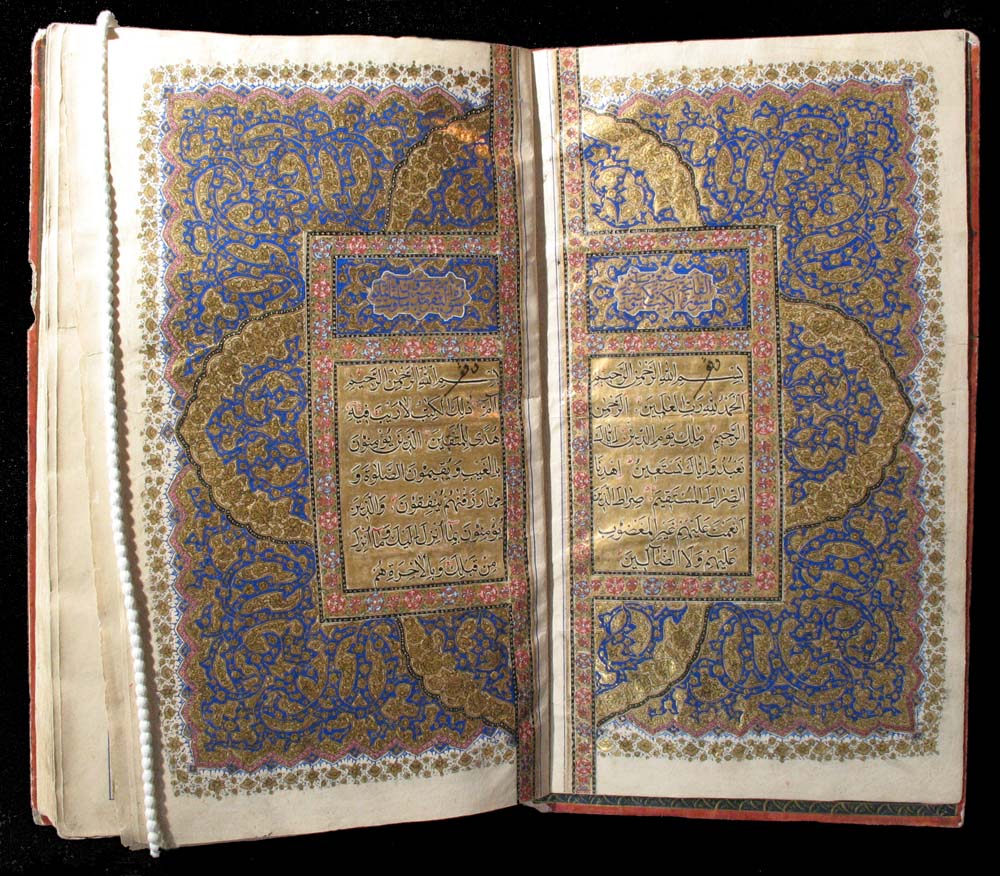

An inscription on the first folio of this manuscript identifies the name of the person for whom the book was made – Danyal ibn Muḥammad, the Emir of Bukhara – and the fact that the book was never to be sold. Calligraphy and illumination in a Qur’an represent a visual aspect of faith. Neither was ever to be a form of independent artistic self-expression, but, rather, acts of worship. Both the scribe and the illuminator prayed before working on books. This Qur’an is a wonderful example of the hierarchy of illumination. The pages with text panels are framed in gold leaf and lapis lazuli (an expensive deep blue pigment found only in Afghanistan) and placed within larger panels bordered with gold leaf vine scrolls. In calligraphic naskhi, surah headings are in blue on gold, with text and vocalization in black and reading signs in red. The text of Surat al-Fati’ah and the first verses of Surat al-Baqarah are underlaid with gold and framed by an ornamental border in gold with a polychrome garland of flowers. Each subsequent page is framed by a multiple border in blue and gold. Each line is separated with a line of gold. Each juz’ and ‘izb is marked by a vertical ornament in dark blue. The rawi is enclosed in a stylized leaf, as are other markers on the margin. Short forms of the names of the surah appear in the upper and outer corner of each page. The last opening, containing Sūrat al-Falaq and Sūrat al-Nās, is illuminated in the same way as the first. The main text is followed by a Du’a’ on three sides of the last two folios. The recto of the last folio remains empty but for a grid. The paper is laid. The binding is lacquer with floral patterns in orange hues on a dark green background on the outside and red roses on an orange background on the inside covers. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Lyndon Smith.

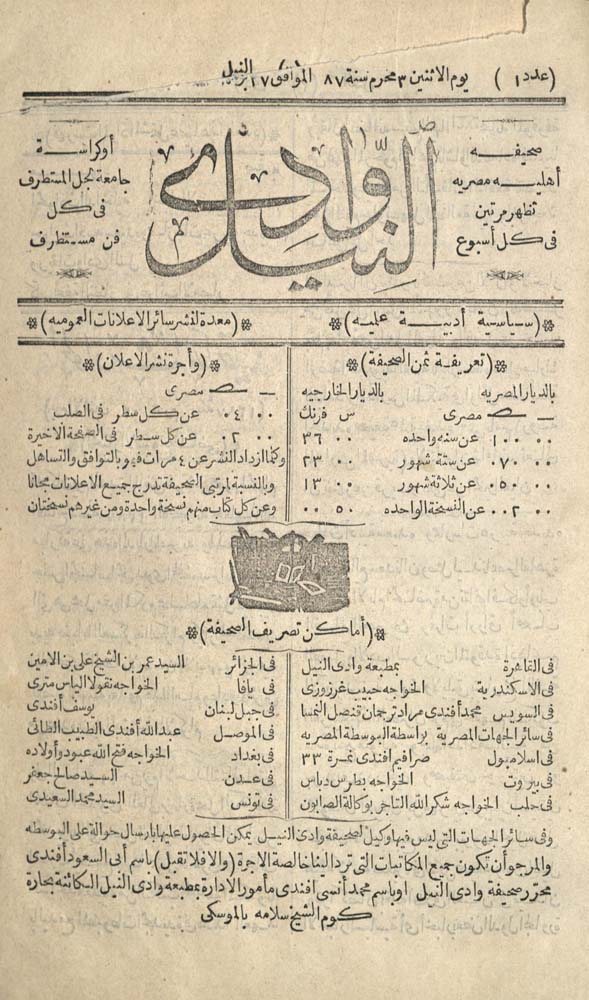

WĀDĪ AL-NĪL

AP95 A6 W33

Published by ‘Abd Allāh Abū al-Su’ūd in Cairo, this semi-weekly was one of two of the first independently published newspapers to appear in the Arab world.

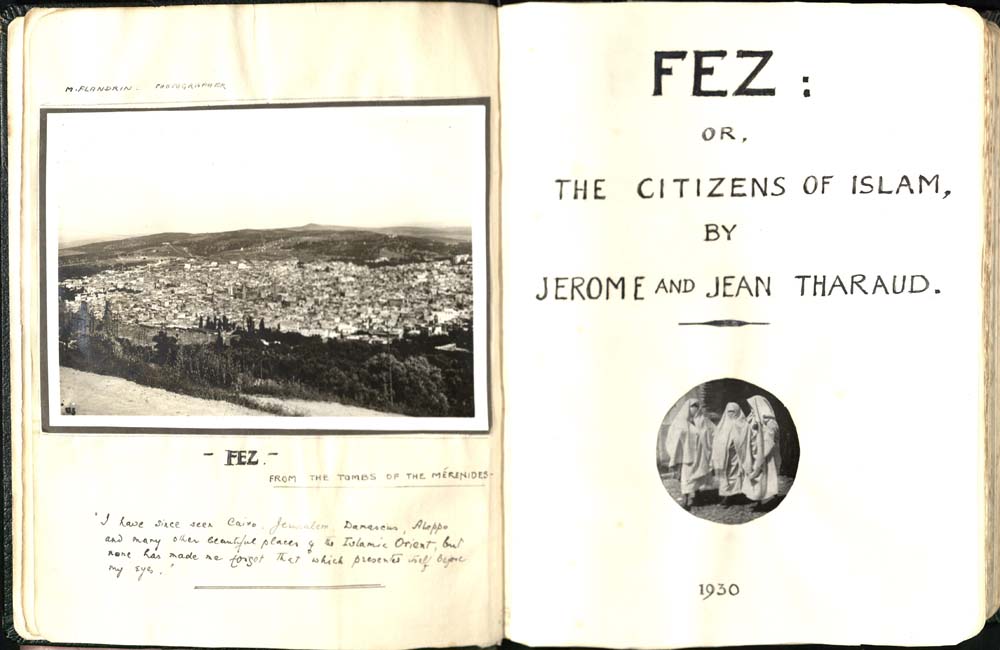

This manuscript is the only known translation of the brothers Tharaud’s Fez; ou, Les Bourgeois de l’Islam, published in Paris in 1930. The book provides information about Morocco at a time in history when this region was strenuously defended from foreign intruders and infidels, still shrouded in mystery for the Europeans. The manuscript is filled with original photographs by several different photographers of monuments, people, and street scenes. The manuscript and photographs concentrate on Fez, a city in north central Morocco, a rich agricultural region, connected by rail to Casablanca, Tangier, and Algeria. The city was noted for its Muslim art and its handicraft industries. It gave its name to the brimless felt caps that were characteristic items of Muslim dress in North Africa. Fez was the capital of several dynasties and reached its zenith under the Merinid sultans in the mid-fourteenth century. It declined under the Sa’adi and Filali dynasties, which chose Marrakech as their capital. The translation has been corrected by at least one other hand in pen or pencil and in some places words have been painted out with correction fluid.

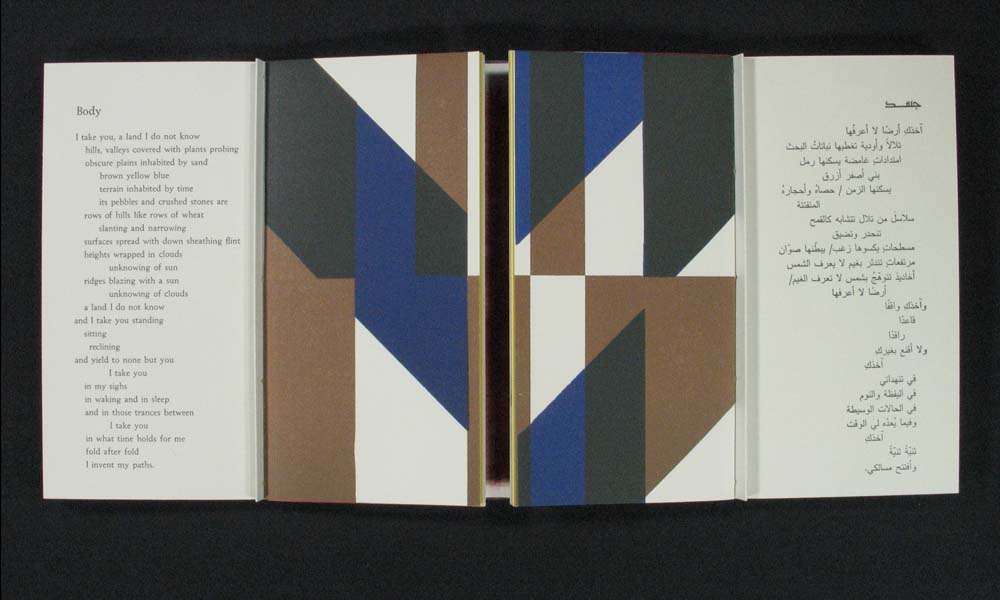

ADONIS, BEGINNINGS: AN ARTIST’S EDITION

Riverdale, MD: Pyramid Atlantic, 1992

N7433.4 B679 A36 1992

Eight poems translated from Arabic by Kamal Boullata & Mirene Ghossein. Book artist Boullata was born in Jerusalem and has lived and worked in Washington, Morroco, and Paris. Four signatures sewn in pairs, with each pair facing the other in French door fashion. Each is punctuated by color linoleum cuts. Printed in handset Weiss Roman type and photo-generated Kufic and naskhi Arabic script on metal relief engravings onto Rives BFK gray paper. Held in a gray paper-covered slipcase. Edition of 40 copies, signed. University of Utah copy is no. 16.

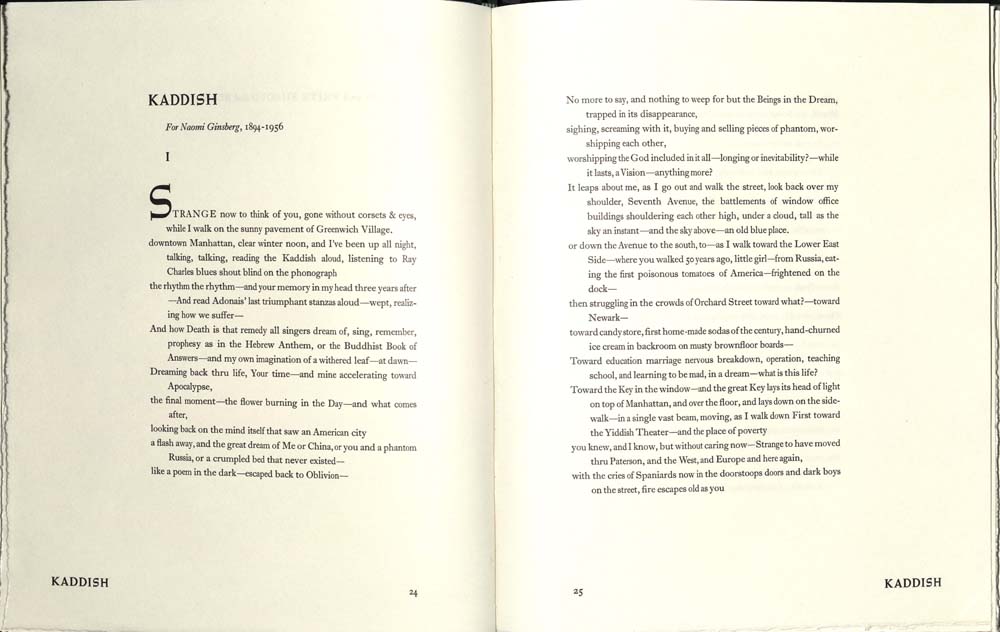

KADDISH: FOR NAOMI GINSBERG, 1894-1956

San Francisco, CA: The Arion Press, 1992

Z232.5 A7 G56 1992

Edition of 226 copies, signed. University of Utah copy is no. 116.

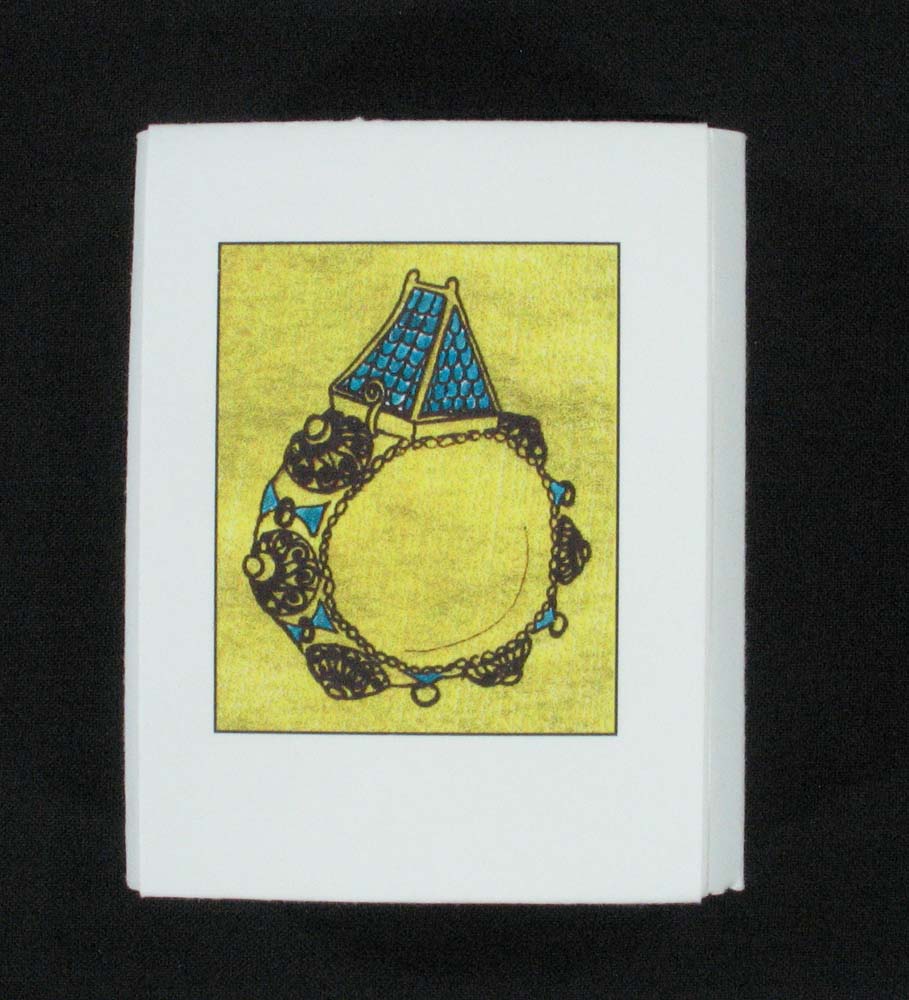

HISTORICAL JEWISH WEDDING RINGS

California: Press de LaPlantz, c1994

N7433.4 L36 H57 1994

Illustrated with hand drawings scanned into a computer, the book is shaped like a building typical of those symbolized on historic Jewish wedding rings and is presented in a representational jewelry box. Edition of three hundred copies, signed and numbered. University of Utah copy is no. 114.

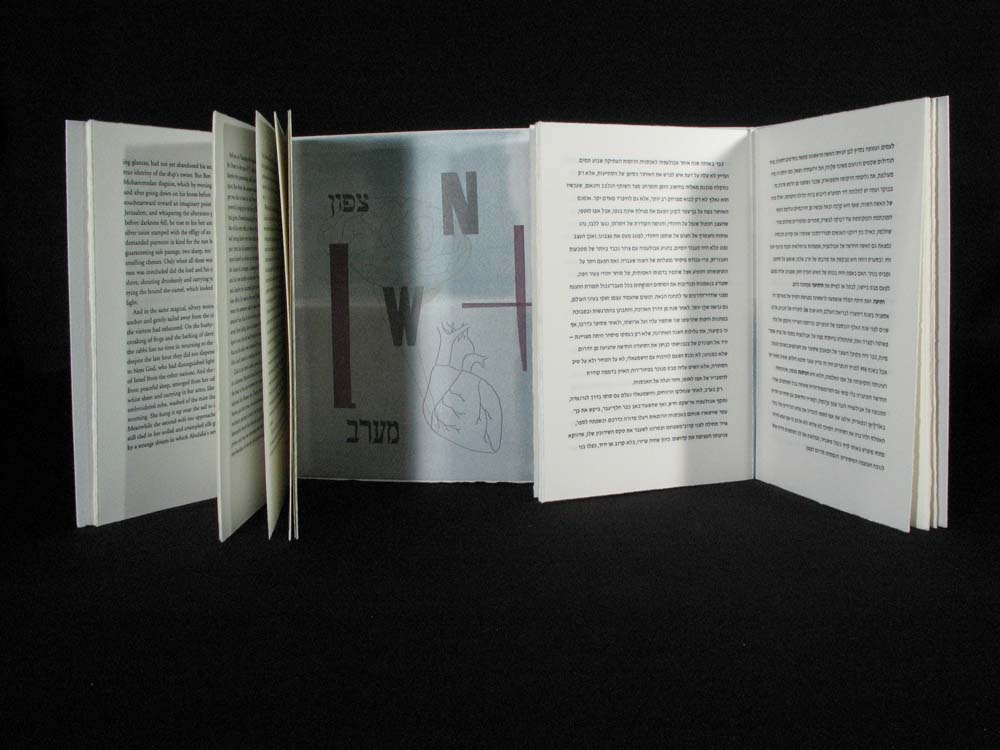

A JOURNEY TO THE END OF THE MILLENNIUM

Huntington Woods, Mich: Land Marks Press, 1999

PJ5054 Y42-M37132 1999

This excerpt from the novel tells the story of a Jewish merchant from Tangiers who travels by boat to Paris to settle a family dispute. Designed, printed, illustrated, and bound by Lynne Avadenka. Printed in Hebrew and English. Bound with double covers that open in opposite directions. The image composition at the back of the book was created using a variety of relief techniques and incorporates visual elements that symbolize the themes of the story: the four directions are printed in both languages; a red cross alludes to the character's journey to the heart of Christian Europe; line drawings of heart and brain reflect the struggle between emotion and intellect. These are framed, triptych style, by mirror images of a boat's curved sail.

FROM THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS

Orinda, CA: Shoestring Press, 2000

PJ1675 F76 2000z

Clay tablets with sketches, etchings, and hieroglyphics recalling ostraca found while excavating in Egypt. Each tablet varies in color, subject, and design. Housed in a decorated leather box.

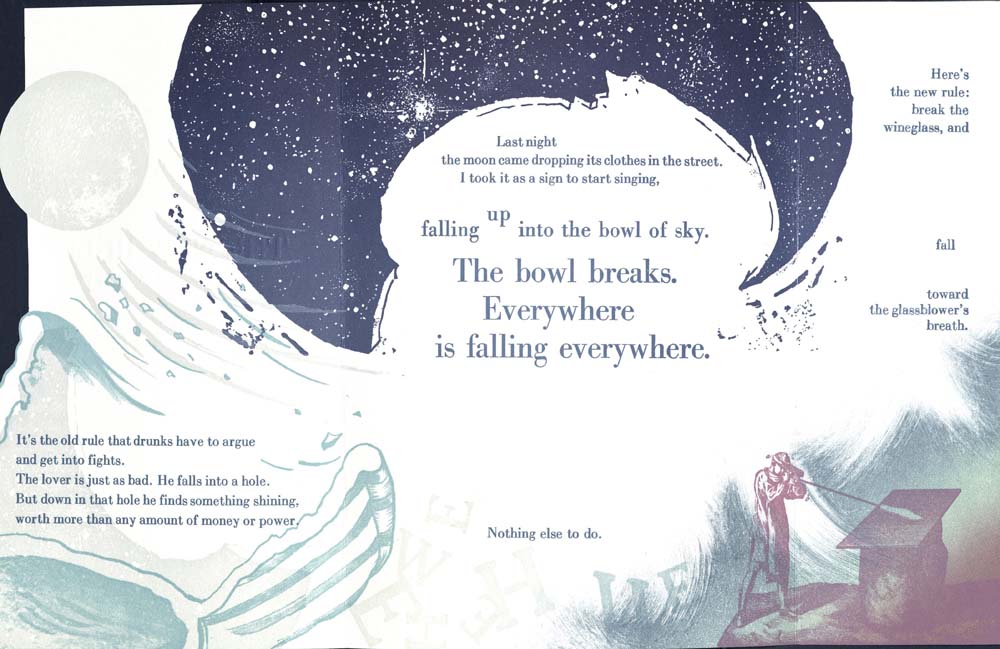

NEW RULE: A POEM BY RUMI

San Diego, CA: Bay Park Press, 2000

N7433.4 R73 N49 2000

A flecked, navy wrapper is folded in three, housing the primary sheet which is, in turn, folded into three, unequal sections. Letterpress from Bodoni and Times Roman on Fabriano Rosaspina Bianco and Fox River Confetti wrapper. Images created using polymer plates, monotypes, linocut, and screen printing. Edition of forty-five copies. University of Utah copy is no. 19.