Roar of Distant Breakers

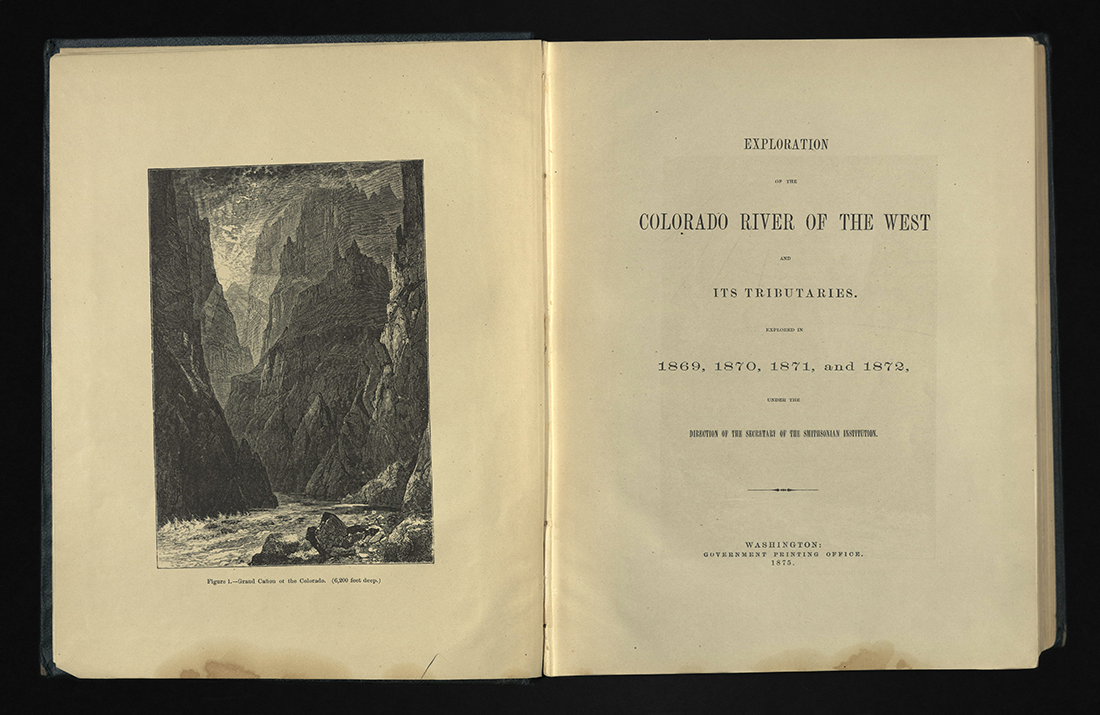

An Incomplete, Illustrated, Chronological Bibliographic Tour of the European Encounter with the American West.

Checklist for Roar of Distant Breakers

Curated by Luise Poulton, 2021

Digital exhibition produced by Lyuba Basin, 2021

ROAR OF DISTANT BREAKERS...

Every culture has its legends.

The books in this exhibition reflect journeys west, across vast land and sea scapes, by the descendants of a people desperate to find freedom, independence, peace, autonomy, and gold. These people, Europeans, found all these things and more on the North American continent. Their discoveries came at a high price for the peoples who had inhabited the continent for thousands of years. The result for them was nothing short of devastating. From the report of Cabeza de Vaca in the sixteenth century to the fiction of Wallace Stegner in the twentieth century, the narratives here are first-hand tellings from Europeans by birth, ancestry, culture, and ideology. These tellings became legend, for good or for bad, creating a distinctly American mythology – a mythology of reorder within a morally privileged space, a defining of possibility. They became the voice of the character of America – its culture and its society – enticing other voices to join in the American dream for freedom, independence, peace, autonomy, and, yes, gold.

This exhibition is dedicated to Gregory C. Thompson, Ph.D, Associate Dean for Special Collections, whose lively, generous, and patient leadership enables extraordinary opportunity for the growth of Special Collections and for the ability of the collections to be engaged with by people around the world.

All over the land are vast and handsome pastures, with good grass for cattle, and it strikes me the soil would be very fertile were the country inhabited and improved by reasonable people.

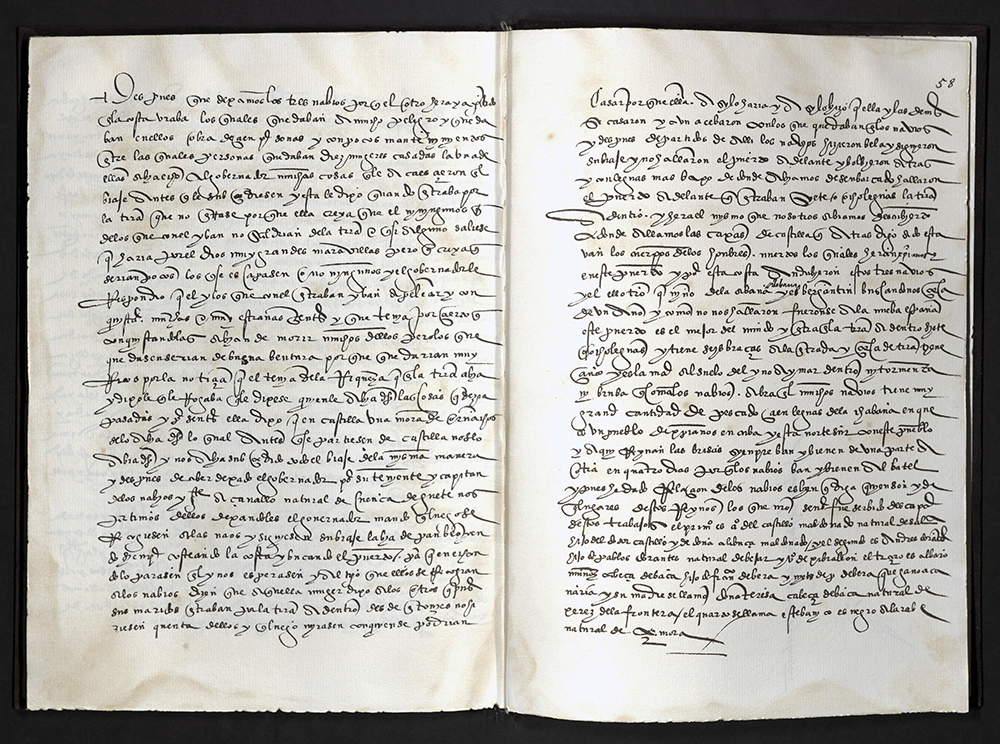

HISTORIA EN ESPANOL DE LAS INDIAS DEL NUOVO MUNDO

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (ca. 1488-ca. 1560)

Espana : G. Blazquez, 1996

E125 N9 N85 1996

Facsimile

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca arrived on the Florida peninsula in 1527, shipwrecked after a harrowing voyage from Cuba. Held in captivity for six years by several groups of Native Americans, only he and three others of his original party survived. The small band, including a North African, Estebanico, made their way overland to the Bay of California. They traveled across Texas, up the Rio Grande, and into southern New Mexico. From there they crossed into Arizona and traveled south to a Spanish outpost. They were the first Europeans to cross the North American continent.

On their approach to the southern tip of the Great Plains, they saw buffalo. Cabeza de Vaca wrote, “These cows come from the north, across the country further on… and are found all over the land… On this whole stretch, through the valleys by which they come, people who live there descend to subsist on their flesh. And a great quantity of hides are met within land.”

According to Cabeza de Vaca, the men were treated as supernatural emissaries and healers by the Native American tribes they met along the way. To the south, toward Mexico, they encountered land and people ravaged by Christians and European slavers. Cabeza de Vaca barely managed to keep his Native American escorts out of their hands.

Estabanico would later lead a Franciscan friar back to the future northern New Mexico to find the towns Cabeza de Vaca had despaired of finding, preparing the way for a larger expedition of Spaniards led by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado. The Zunis, rightly suspicious of his motives, killed Estabanico, leaving Friar Marcos to return to Mexico with faulty stories of wealthy cities. These cities turned out to be the pueblos.

Cabeza de Vaca’s story of his odyssey, written in 1542, was an official report to the king of Spain, detailing the hardships of the expedition and his unintentional exploration of what is now Mississippi, Arkansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and California. What Cabeza de Vaca saw and described were peoples, rivers, mountains, and plains all, until then, unknown to Europeans.

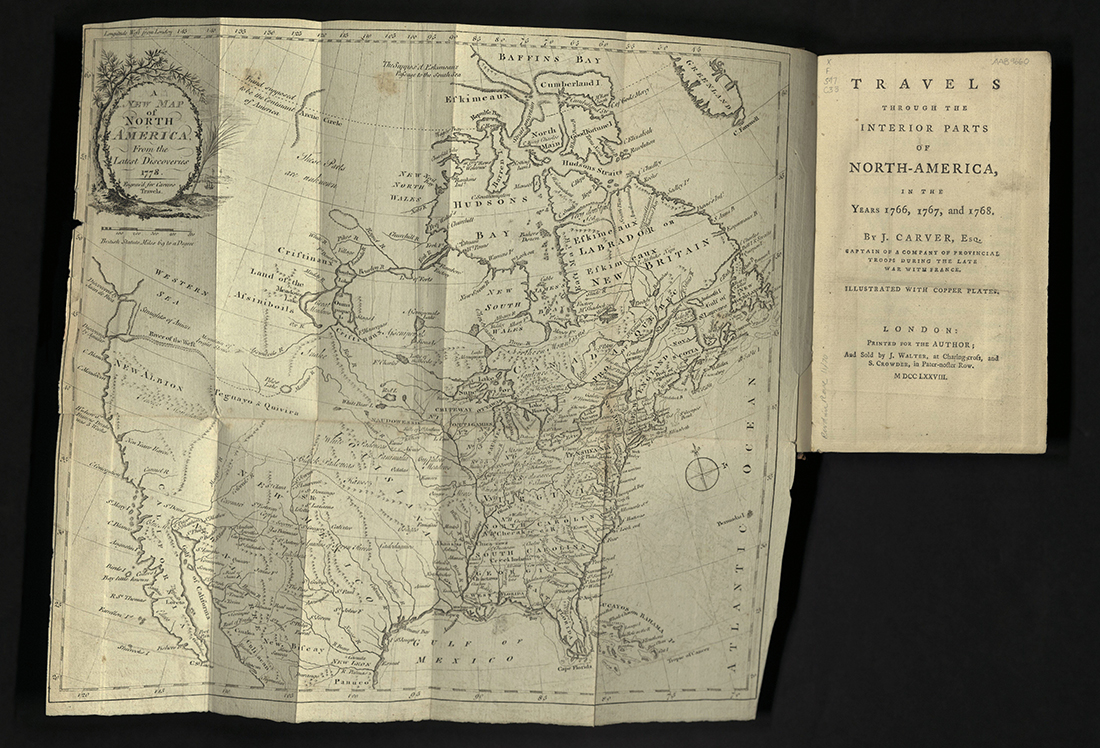

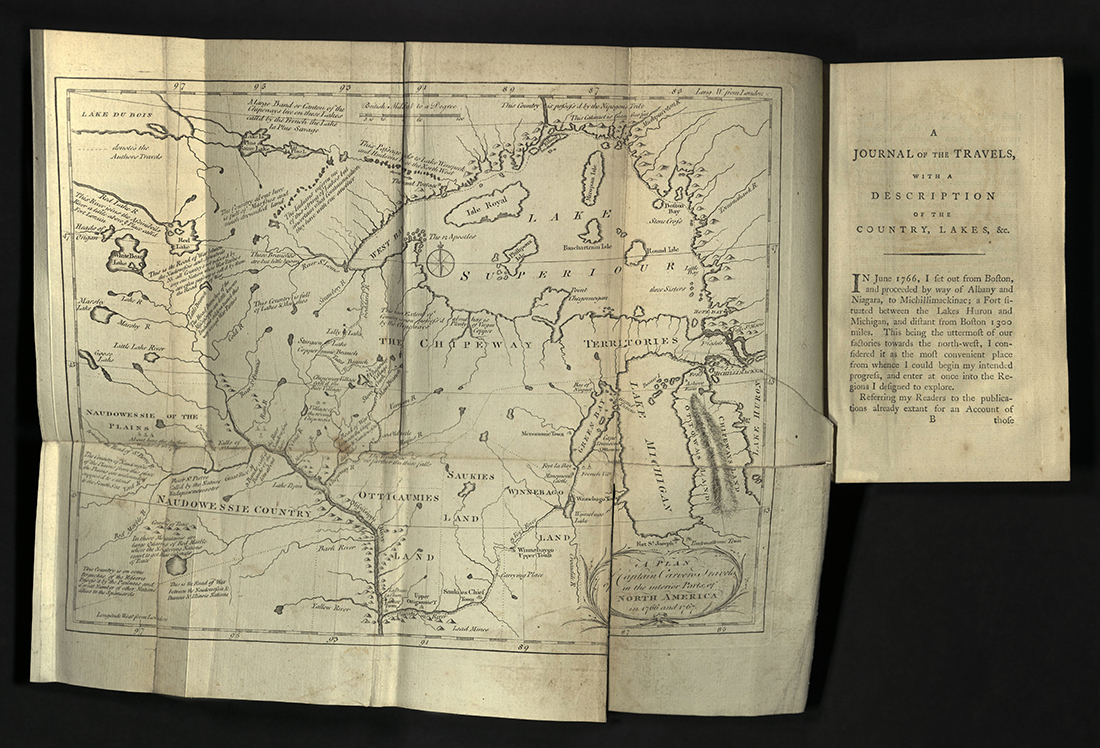

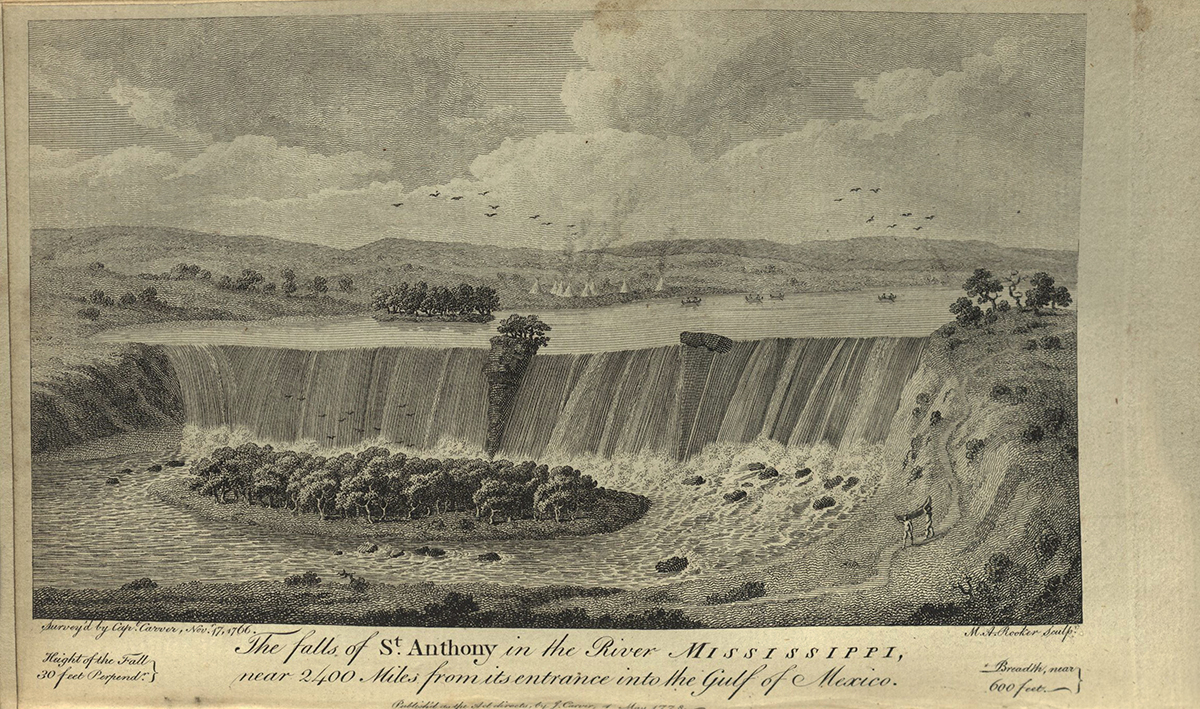

TRAVELS THROUGH THE INTERIOR PARTS OF NORTH-AMERICA IN THE YEARS 1766, 1767, AND 1768

Jonathan Carver (1710-1780)

London: Printed for the author, sold by J. Walter [etc.], 1778

First edition

F597 C33

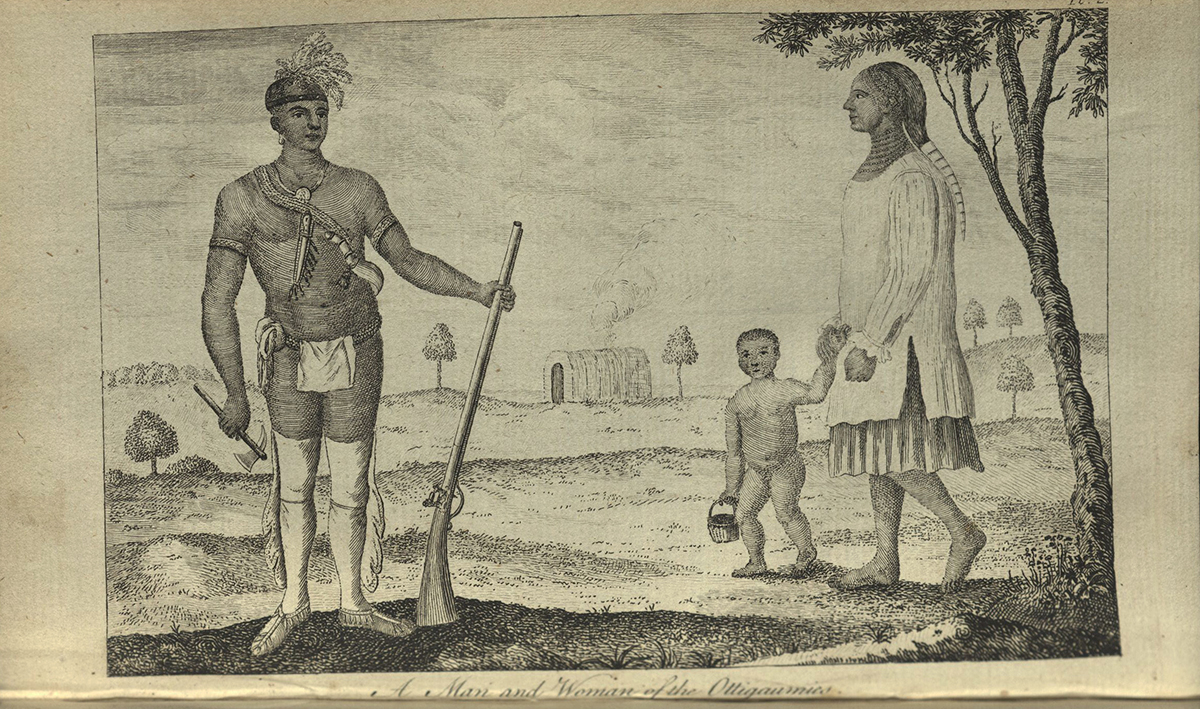

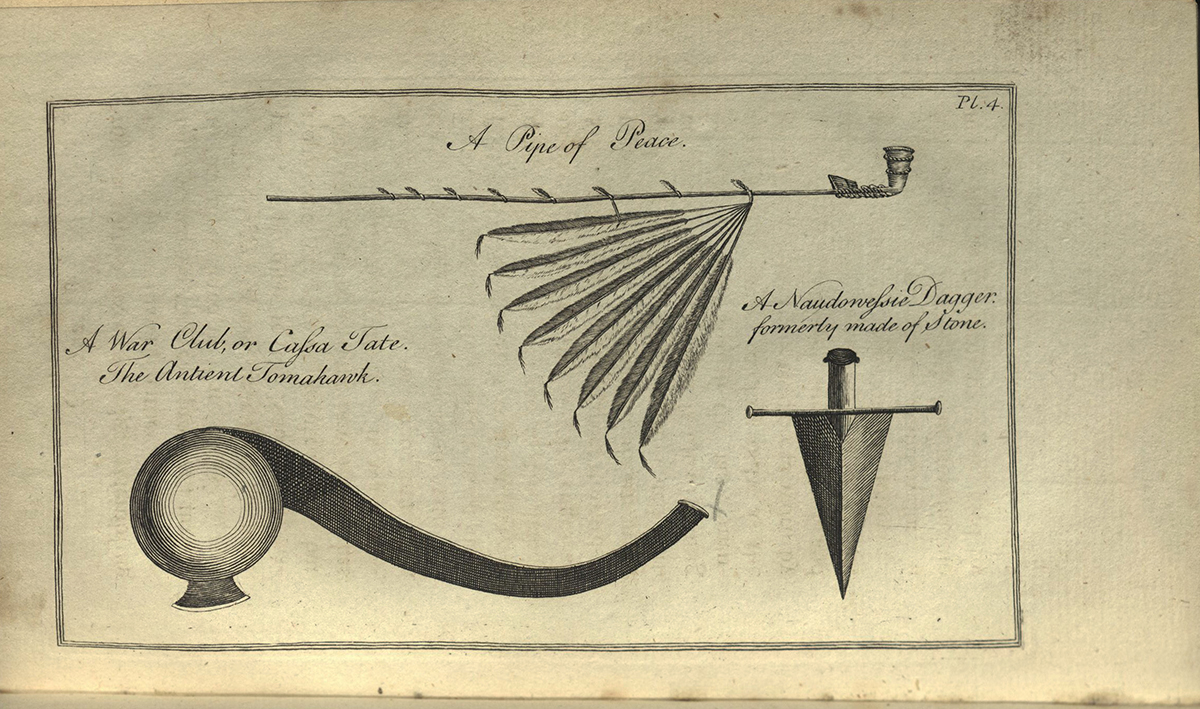

Peace between Great Britain and France at the close of the French and Indian Wars in 1763 brought eastern Minnesota under the British flag, thus opening the vast territory to British fur traders. At the time, Jonathan Carver was the mapmaker and advance man on an expedition led by Captain James Tute. Inspired by Major Robert Rogers, commandant at Fort Mackinac, the expedition party intended to cross the continent in quest of the Northwest Passage. In advance of this attempt, Carver spent the winter of 1766 with the Sioux along the Minnesota River. He traveled further west than any other English explorer before the American Revolution. In the end, the original plan was abandoned, but Carver’s account of his adventures became a best seller of its day. Thousands of copies were sold in North America and in Europe, giving readers their first glimpse of Minnesota territory.

Illustrated with two engraved folding maps and four engraved plates (one a view of the Falls of St. Anthony, which is the first illustration of both the Falls and what is now the site of Minneapolis.)

The country around them is extremely beautiful. It is not an uninterrupted plain where the eye finds no relief, but composed of many gentle ascents, which in the summer are covered with the finest verdure, and interspersed with little groves, that give a pleasing variety to the prospect.

They go without any covering for the thigh, except… round the middle, which reaches down half way the thighs; but they make for their legs a sort of stocking either of skins or cloth: these are sewed as near to the shape of the leg as possible, so as to admit of being drawn on and off. The edges of the stuff of which they are composed are left annexed to the seam, and hang loose for about the breadth of a hand: and this part, which is placed on the outside of the leg, is generally ornamented by those who have any communication with Europeans, if of cloth, with ribands or lace, if of leather, with embroidery and porcupine quills curiously coloured. Strangers who hunt among the Indians in the parts where there is a great deal of snow, find these stockings much more convenient than others.

But the women that live to the west of the Mississippi, viz. the Naudowessies, the Assinipoils, &c. divide their hair in the middle of the head, and form it into two rolls, one against each ear. These rolls are about three inches long, and as large as their wrists. They hang in a perpendicular attitude at the front of each ear, and descend as far as the lower part of it.

The dagger… is peculiar to the Naudowessie nation, and of ancient construction, but they can give no account how long it has been in use among them. It was originally made of flint or bone, but since they have had communication with the European traders, they have formed it of steel. The length of it is about ten inches, and that part close to the handle nearly three inches broad. Its edges are keen, and it gradually tapers towards a point…This curious weapon is worn by a few of the principal chiefs alone, and considered both as a useful instrument, and an ornamental badge of superiority.

The American is a new man, who acts upon new principles; he must therefore entertain new ideas, and form new opinions... Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world... An immigrant when he first arrives... no sooner breathes our air than he forms new schemes, and embarks in designs he never would have thought of in his own country... He begins to feel the effects of a sort of resurrection; hitherto he had not lived, but simply vegetated; he now feels himself a man... Judge what an alteration there must arise in the mind and thoughts of this man; ... his heart involuntarily swells and glows; this first swell inspires him with those new thoughts which constitute an American.

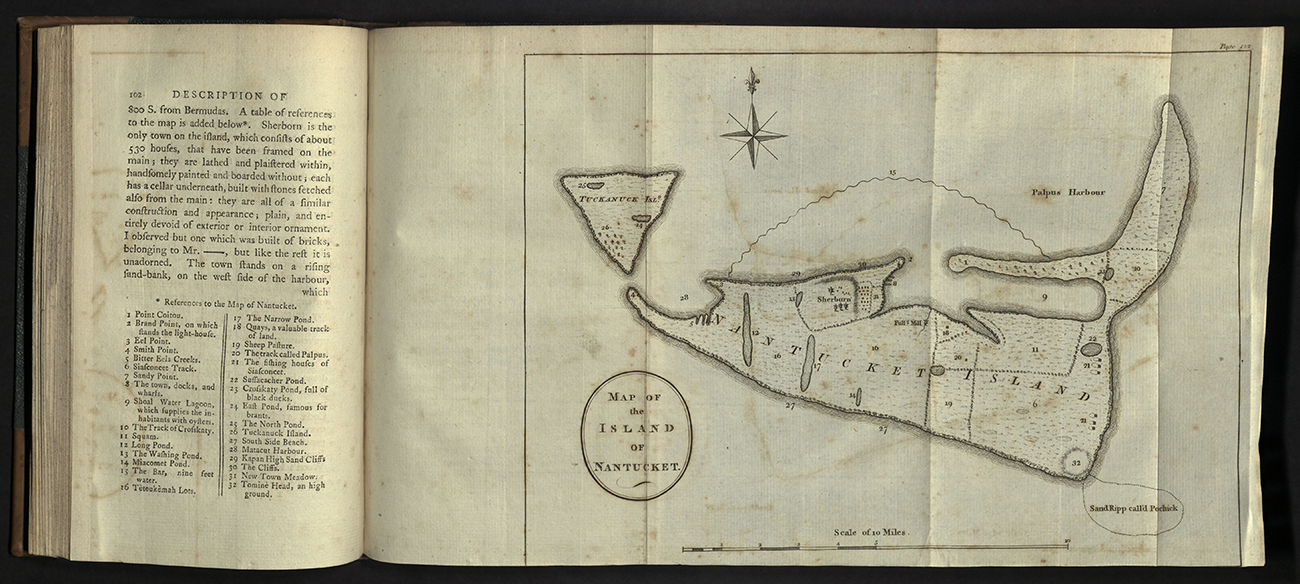

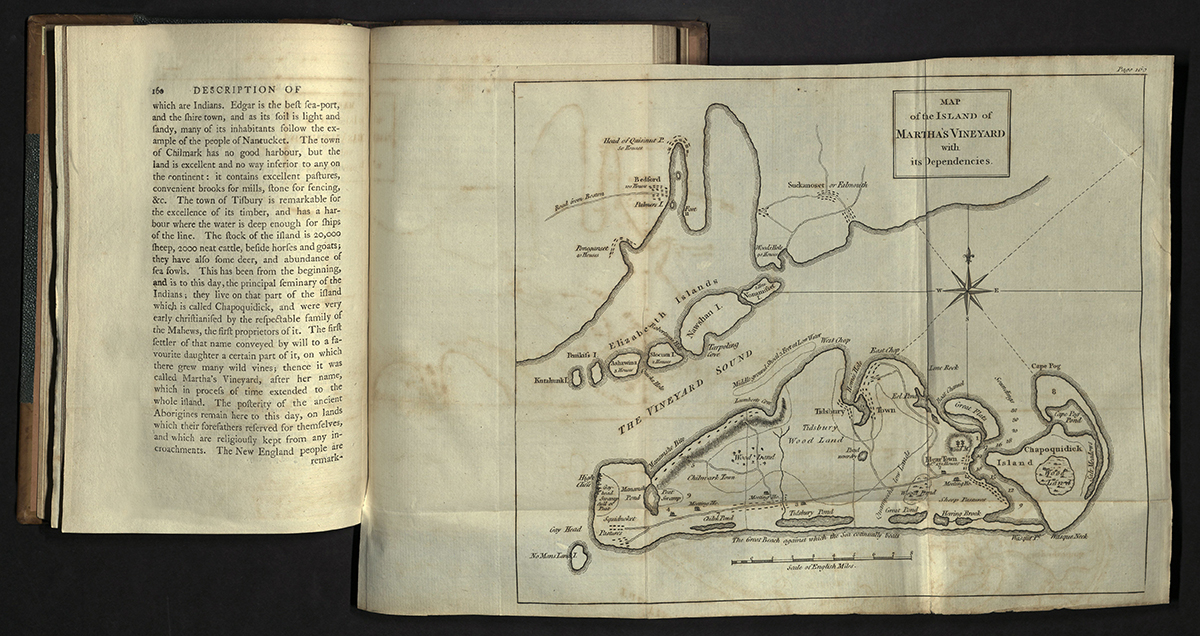

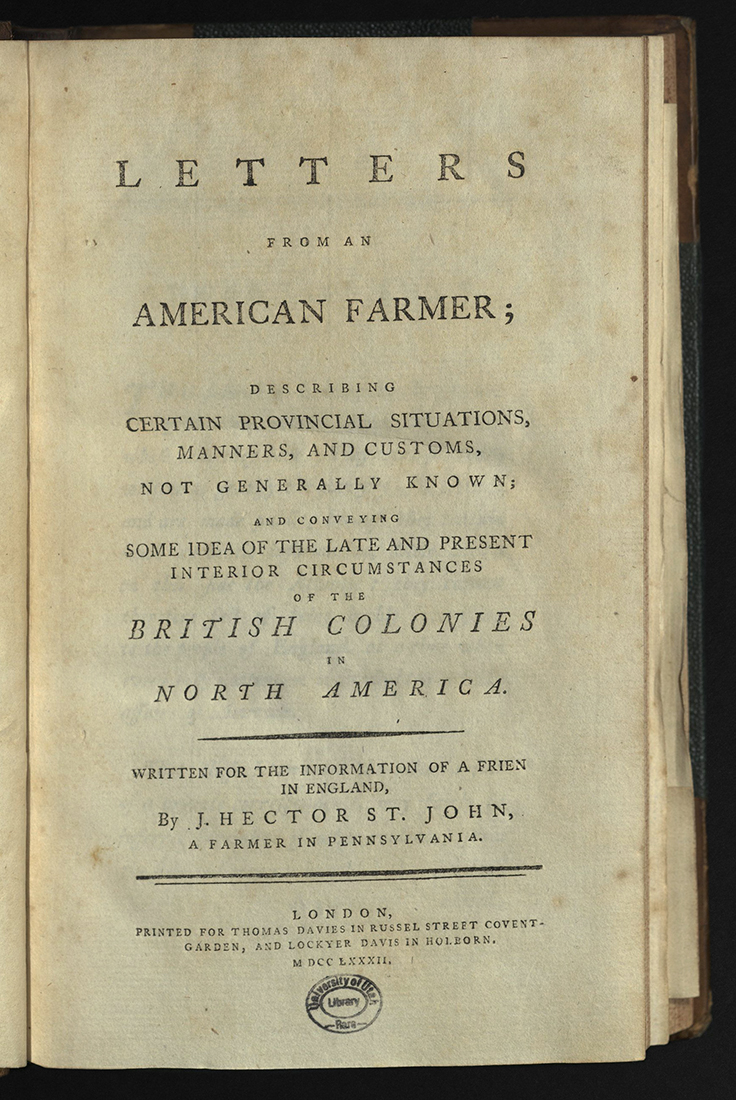

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN FARMER ...

J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur (1735-1813)

London: Printed for Thomas Davies, 1782

First edition

E163 C82

Not long after the American Revolution, J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, a French observer of American society, asked a question that Americans would grow fond of answering: “What, then, is the American, this new man?” Crevecoeur spent three decades pioneering and traveling in the American West, offering up a theory of frontier influence on the American character. The maps of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket are apparently the first separately printed delineations of those islands.

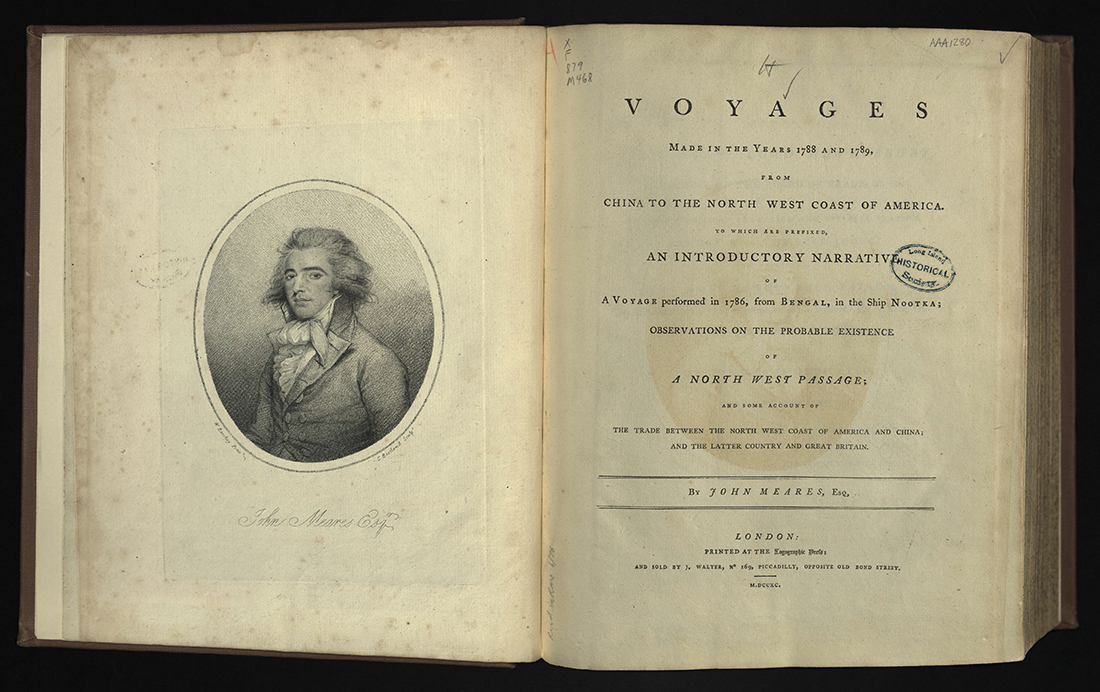

VOYAGES MADE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1789 ...

John Meares (1756-1809)

London: Printed at the Logographic Press, 1790

First edition

F879 M468

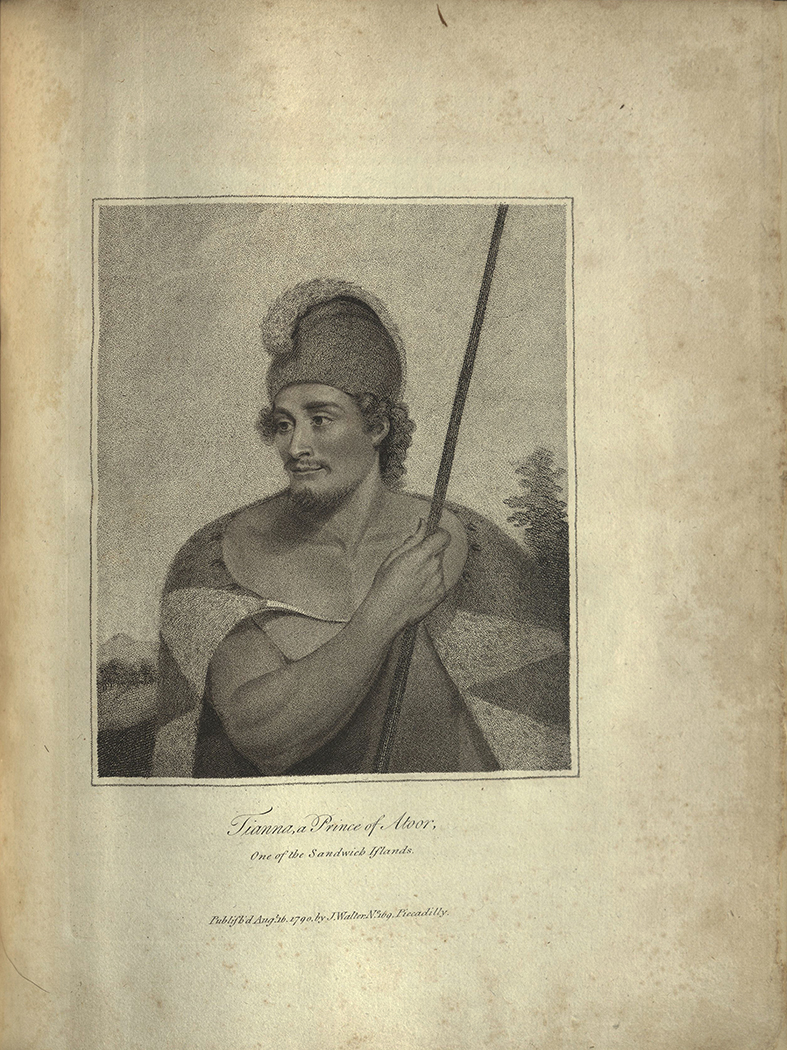

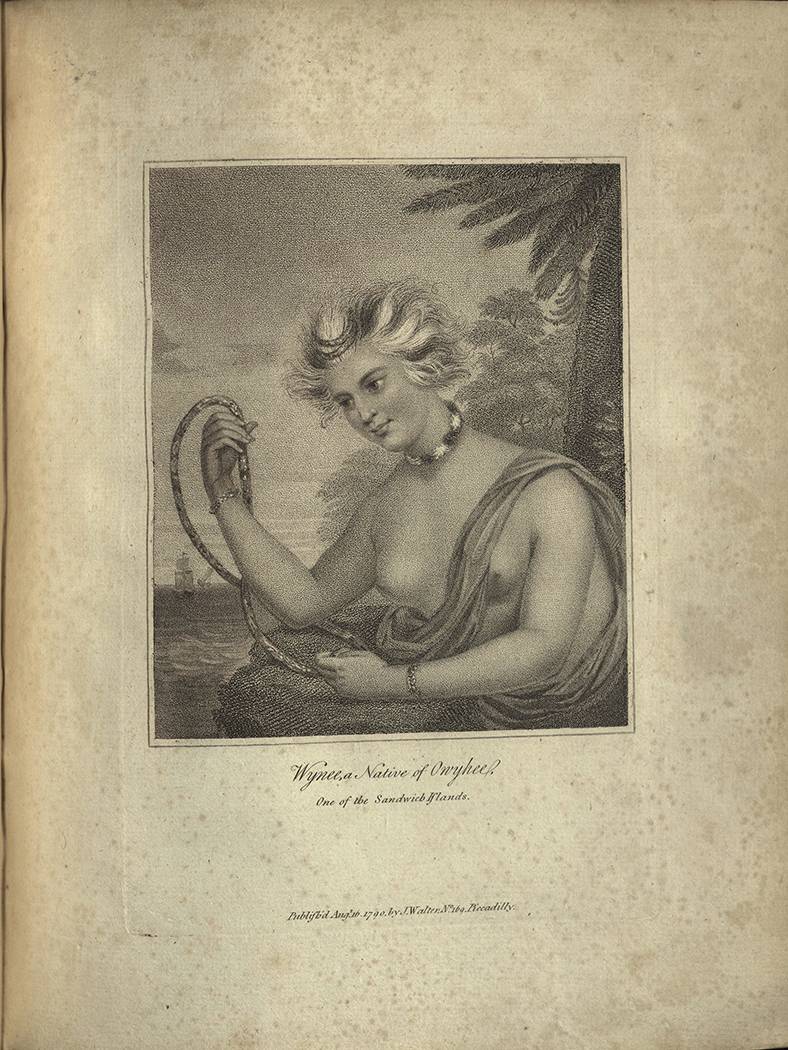

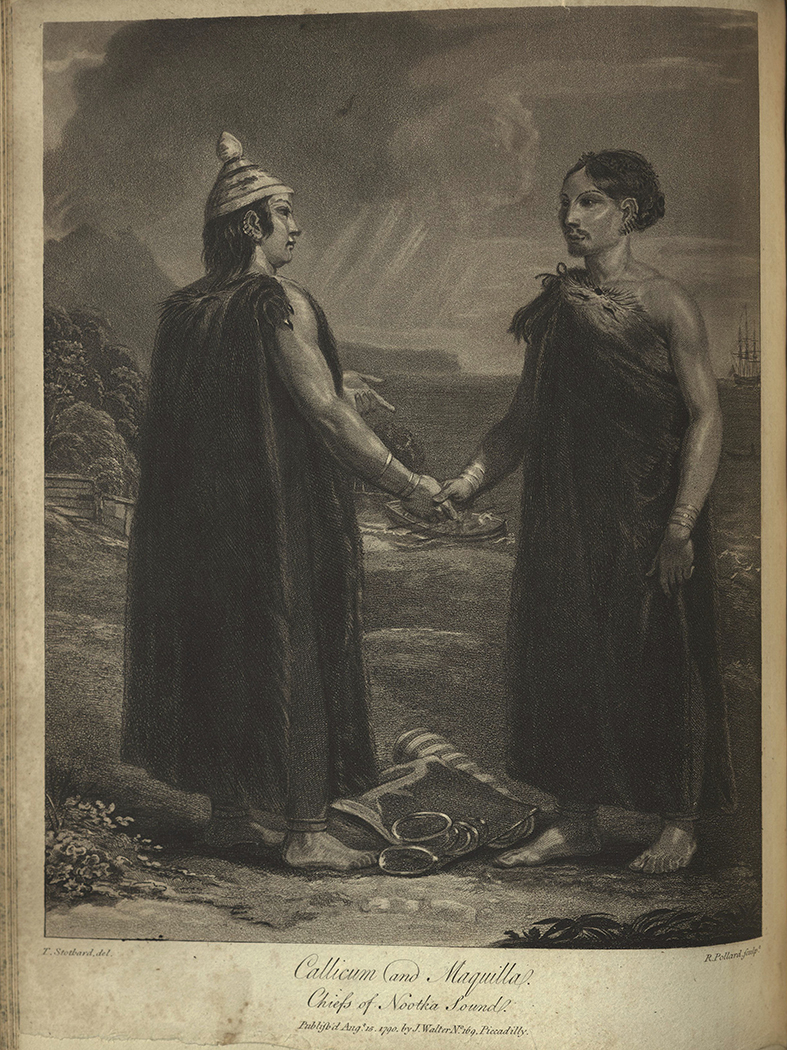

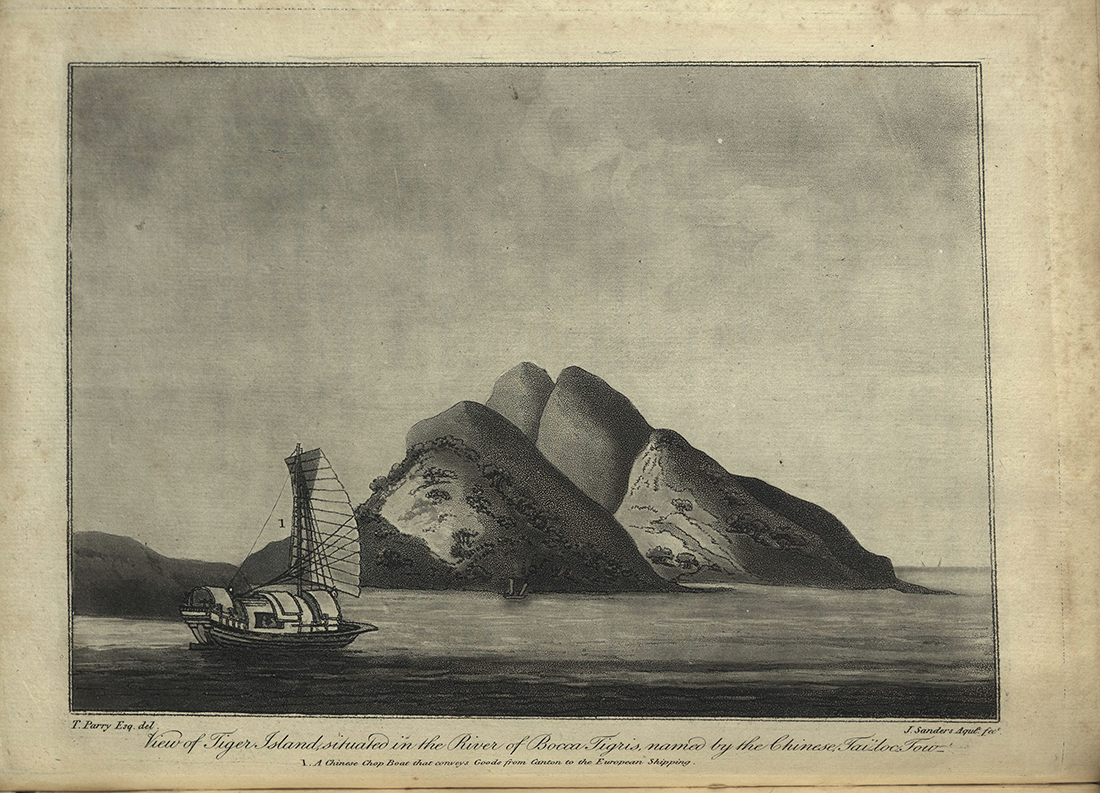

John Meares was a lieutenant in the British Navy and fought in the American Revolution. He became a captain in the merchant service and established a company in Calcutta for developing trade with Northwest American settlements. In 1786, Meares sailed on the ship Nootka for Prince William Sound and after securing a right of free trade from the native tribes there, returned to China.

All Europeans are prohibited from entering the city of Canton; and if any should persist in paying it a clandestine visit, as some have done, they are severely bambooed and turned back again. The Chinese call an European a Fanqui.

It is indeed a very evident, as well as mortifying proof, that the English name does not possess that consequence with the Chinese, which it merits in every country and corner of the globe, from their conduct towards the East India Company’s servants, who constantly remove to the Portuguese city of Macao for several months of the year.

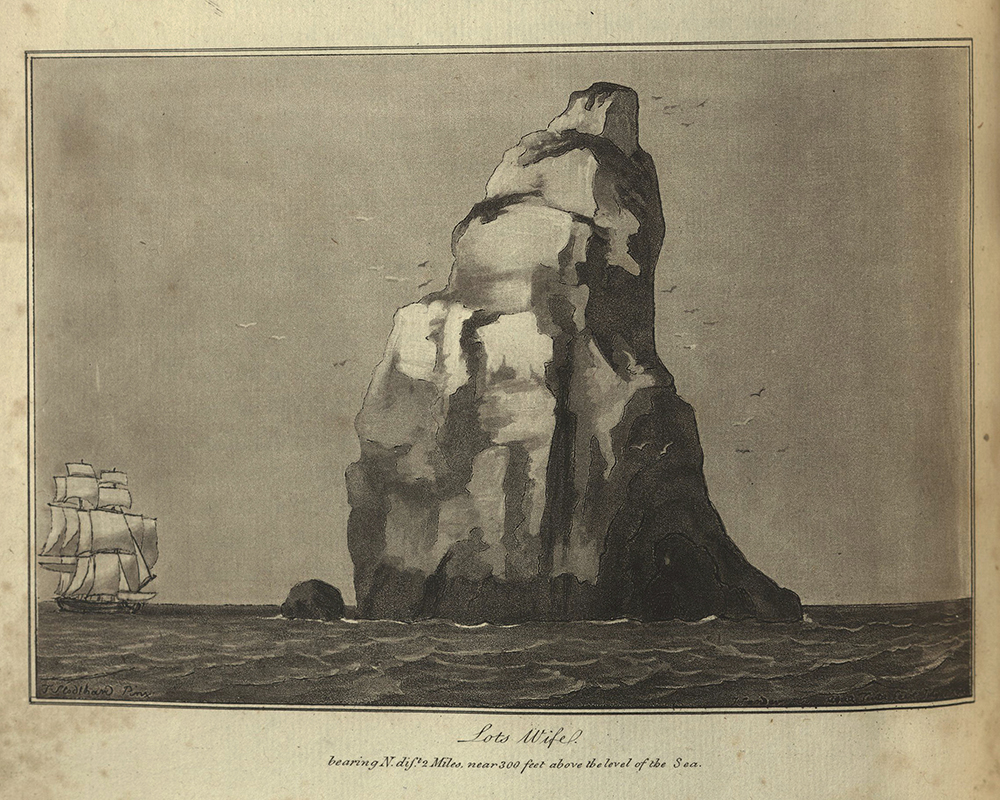

Its appearance did, indeed, very strongly resemble a first-rate man of war, under a croud of sail; and such was its shape, that, at a certain distance, it held forth to the eye the form of every particular sail belonging to a ship. As we ranged up with this rock, our surprise was proportionably augmented, and the sailors were more disposed to believe that some supernatural power had suddenly transformed it into its present shape. It obtained the name of Lot’s Wife, and is one of the most wonderful objects, taken in all its circumstances, which I ever beheld.

As soon as the tide was at its proper height, the English ensign was displayed on shore at the house, and on board the new vessel, which, at the proper moment, was named the North West America, as being the first bottom every built and launched in this part of the globe.

For this voyage to the American coast, Meares used false papers in order to evade Spanish claims to the coast and circumvent two royally chartered monopolies. The Indians called him “Aitaaita Meares,” or “Lying Meares.” Meares was asked by a legitimate British trader to never return to America, to which he agreed. In 1789, using false papers again, he dispatched the Argonaut and Princess Royal to meet a third, the Iphigenia, in Nootka Sound on the coast of Vancouver Island. The Iphegenia arrived first and was attacked by Spanish ships. The Spaniards claimed the area as their own, seizing the Argonaut and Princess Royal when they arrived. Meares protested to the British government and the House of Commons demanded reparation from the Spanish government. The Spanish were not quick to provide restitution and the English assembled a large fleet to go against them. The political excitement over this stand-off caused great interest in Meares’ activities and encouraged him to write of his travels. The publication of this work led to even more controversy in England. Its accuracy was questioned by many. Nonetheless, Meares’ book helped British claims to the northwest coast of the American continent.

This was the real situation of things, says Senor Quadra, who offers to demonstrate in the most unequivocal manner that the injuries, prejudices, and usurpations, as represented by Captain Meares, were chimerical: that Martinez had no orders to make prize of any vessels, nor did he break the treaty of peace, or violate the laws of hospitality: that the natives will affirm, and that the documents accompanying his letter will prove, that Mr. Meares had no other habitation on the shores of Nootka than a small hut, which he abandoned when he left the place, and which did not exist on the arrival of Martinez: that he bought no land of the chiefs of the adjacent villages; that the Ephigenia did not belong to the English; that Martinez did not take or detain the least part of her cargo;… These circumstances duly considered, adds Senor Quadra, it is evident that Spain has nothing to deliver up, nor damage to make good; but that he was desirous of removing every obstacle to the establishment of a solid and permanent peace, he was ready, without prejudice to the legitimate right of Spain, to cede to England the houses, offices, and gardens, that had with so much labour been erected and cultivated… observing at the same time, that Nootka ought to be the last or most northwardly Spanish settlement, that there the dividing point should be fixed, and that from thence to the northward should be free for entrance, use and commerce to both parties…

A VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY TO THE NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN ...

George Vancouver (1757-1798)

London: Printed for G. G. and J. Robinson, etc., 1798

First edition

G420 V22 1798

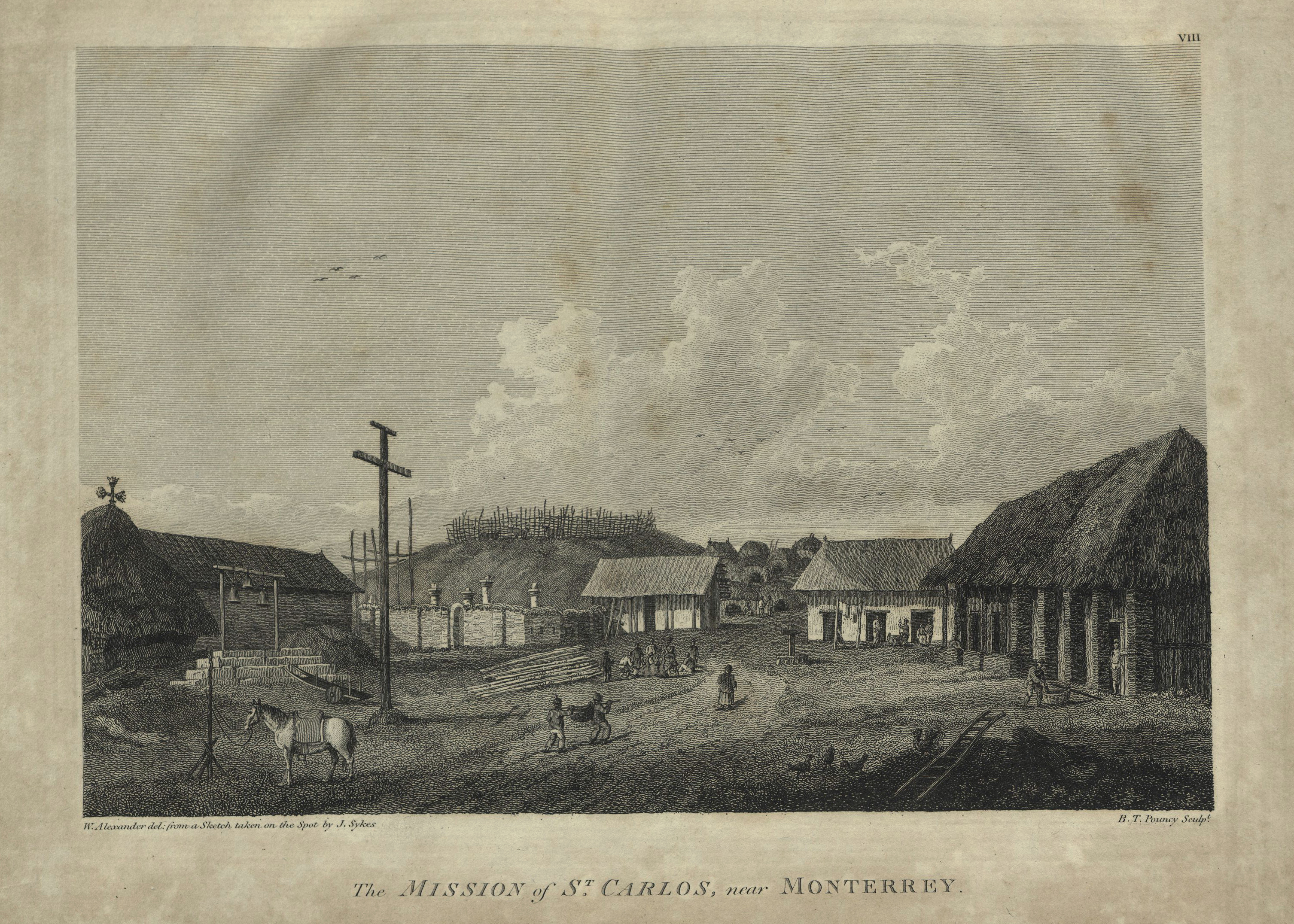

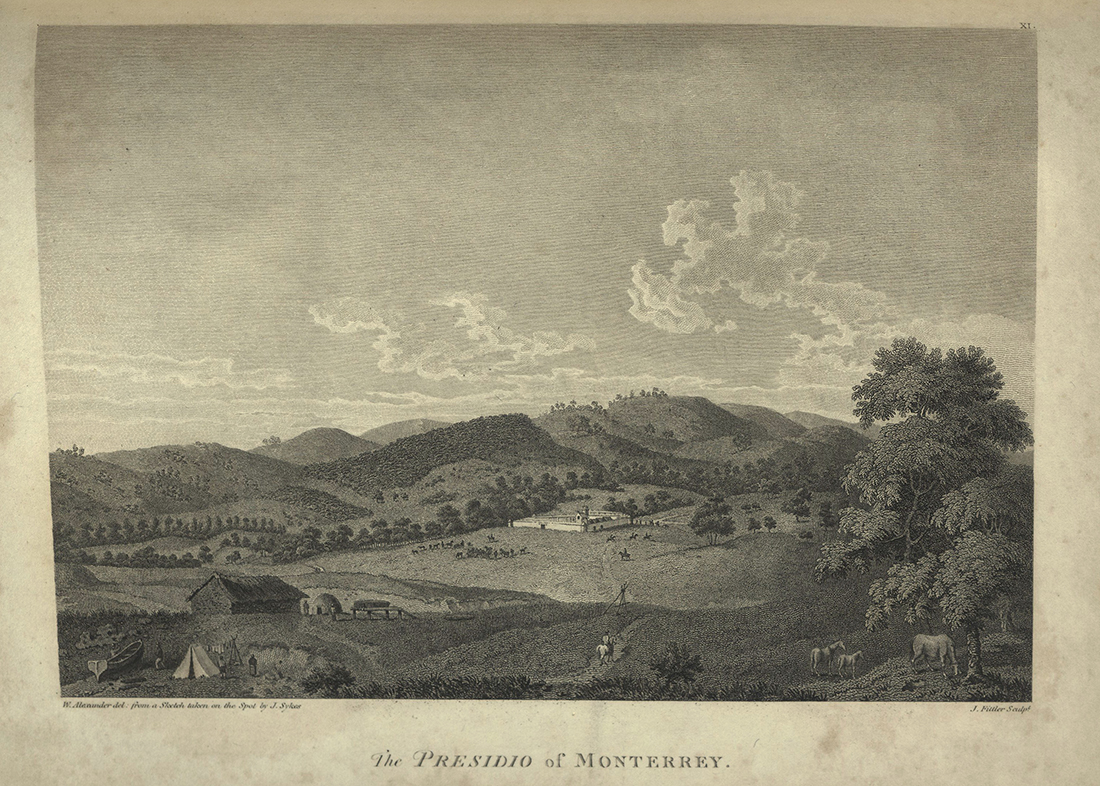

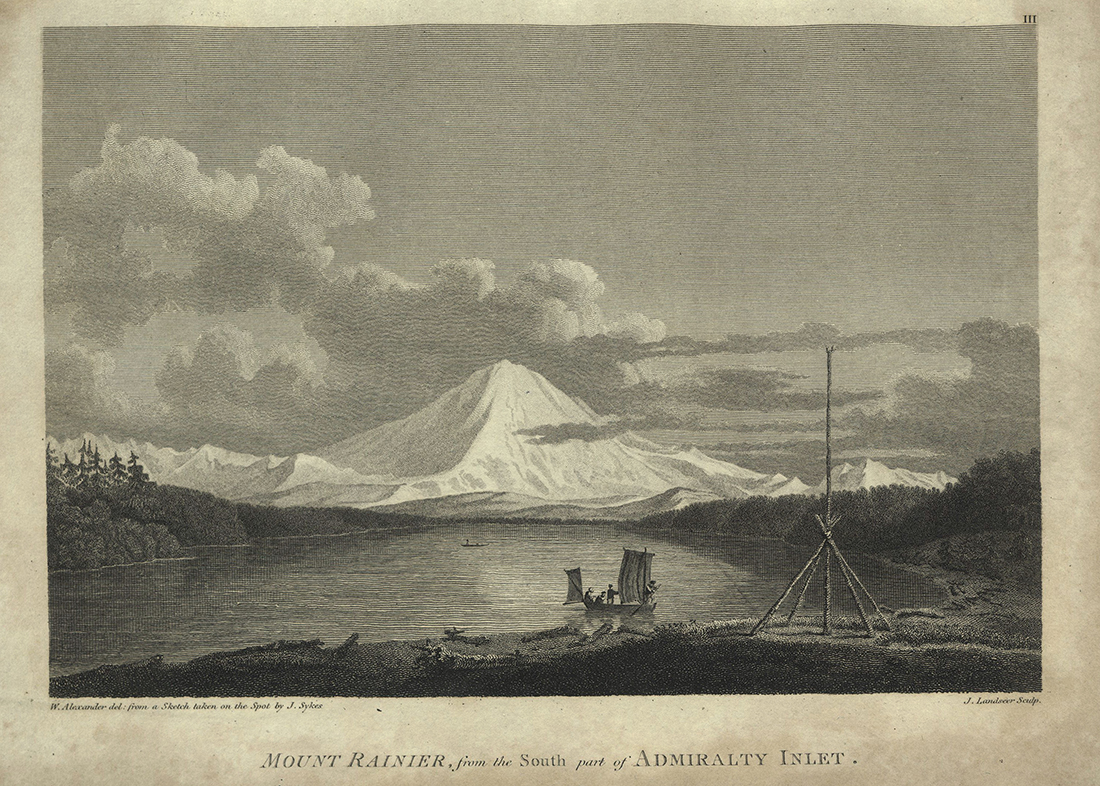

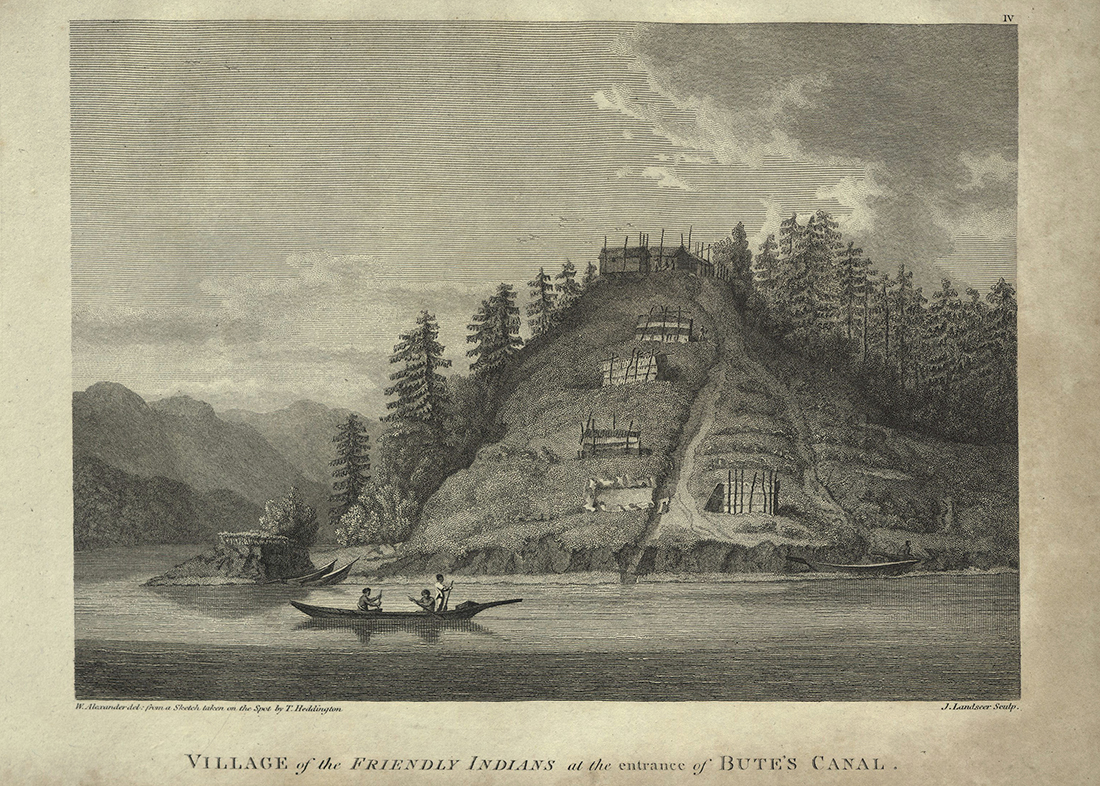

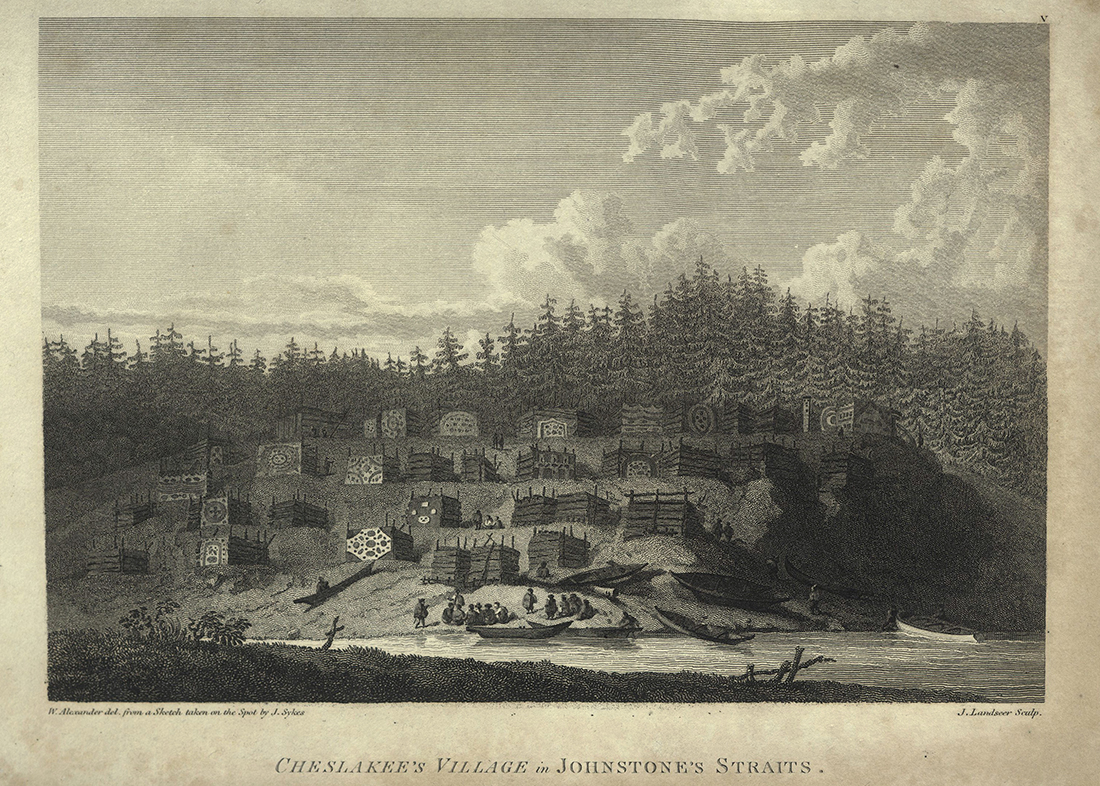

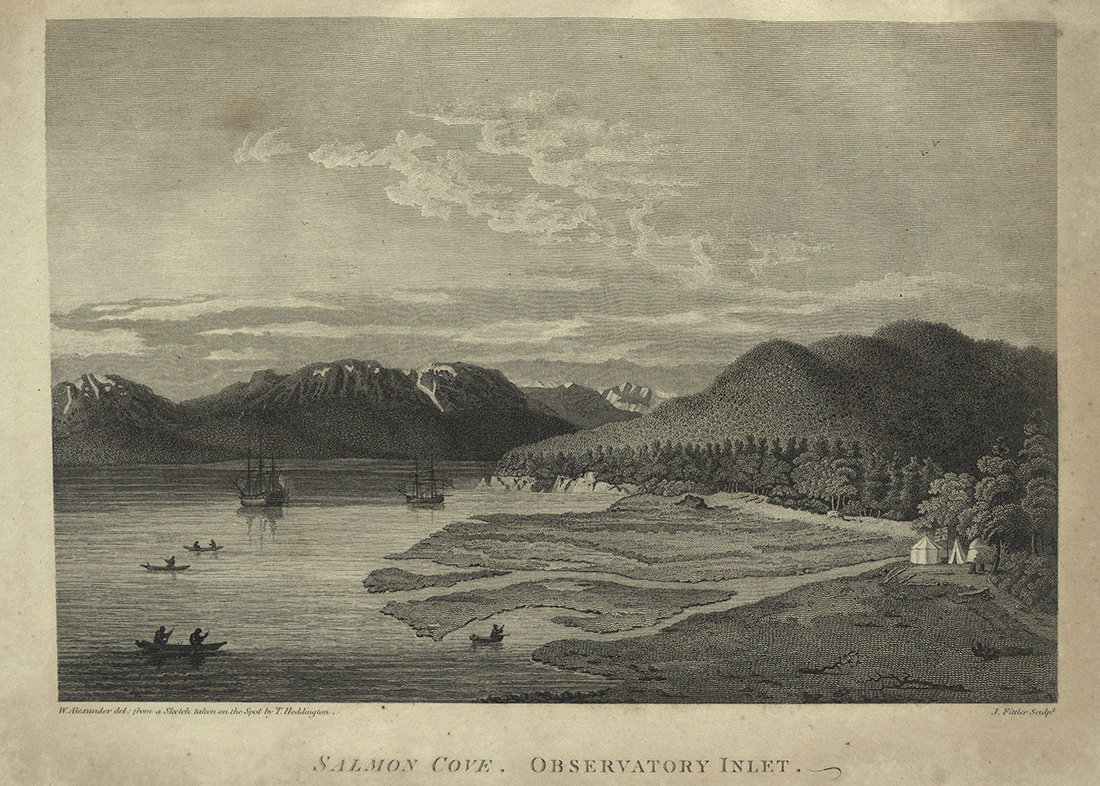

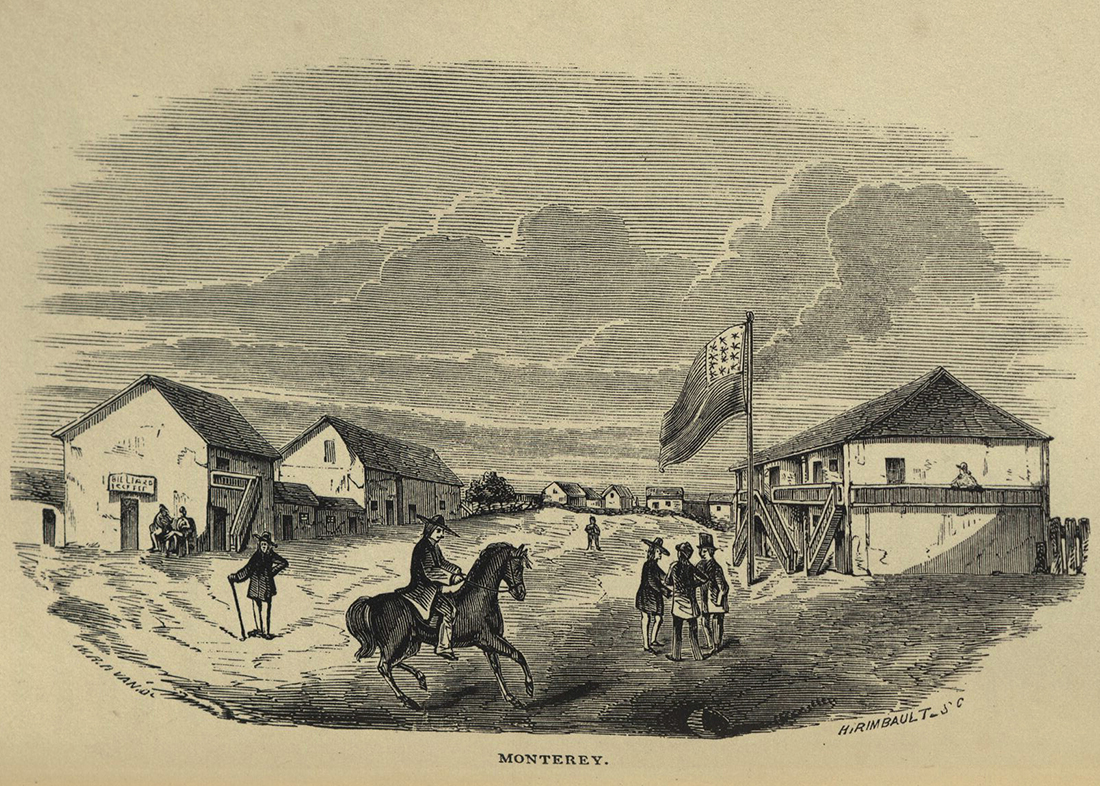

George Vancouver, who had served with Captain Cook’s second and third voyages, was made commander of a grand-scale expedition to reclaim from the Spanish British rights resulting from the Nootka Convention at Nootka Sound. He was to thoroughly examine the California coast in order to find a possible passage to the Atlantic and to learn what establishments had been founded by other powers. Vancouver surveyed the northwest coast, visited San Francisco and Monterey, spent the winter in the Sandwich Islands, returned to California and revisited San Francisco. He then went on to Cape Mendocino, Bodega Bay and back to Monterey. He visited the Sandwich Islands again, took possession of Owhyhee and then returned again to the northwest coast and on back to Monterey. From there he set sail to return to England by Cape Horn.

In 1792, Vancouver became the first European to explore Puget Sound. Vancouver’s voyage exploring the northwest coast of America produced the first accurate charts of the area. Vancouver, a self-conscious imperialist, was bent on expanding the English empire. He claimed an enormous unexplored interior basin for Britain, a chunk of territory whose size no one knew and with an enormous river whose source was unknown.

Illustrated with seventeen engravings, including views of the Mission of San Carlos and the Presidio of Monterey thought to be the first published views of California; one small map; and eight folding maps.

On our arrival, we were received by the reverend fathers with every demonstration of cordiality, friendship, and the most genuine hospitality… The houses were constructed nearly after the manner of those at the presidio, but appeared to be more finished, better contrived, were larger, and much more cleanly.

... when I visited him at the Presidio; I was reduced to the necessity of sending him the next day the full explanation of the objects of our voyage, and of the motives that had induced me to enter the ports under his jurisdiction. In this I stated, that I had been intrusted by His Britannic Majesty with a voyage of discovery, and for the exploring of various countries in the pacific ocean; of which the north-west coast of America was one of the principal objects.

The native appeared to be a wandering people, who sometimes made their excursions individually, at other times in considerable parties; this was apparent by their habitations being found single and alone, an well as composing tolerably large villages.

For having passed round the point, we found the inlet to terminate here in an extensive circular compact bay, whose waters washed the base of mount Rainier, though its elevated summit was yet at a very considerable distance from the shore, with which it was connected by several ridges of hills rising towards it with gradual ascent and much regularity. The forest trees and the several shades of verdure that covered the hills gradually decreased in point of beauty until they became invisible; when the perpetual clothing of snow commenced, which seemed to form a horizontal line from north to south along this range of rugged mountains, from whose summit mount Rainier rose conspicuously, and seemed as much elevated above them as they were above the level of the sea; the whole producing a most grand, picturesque effect.

Here was found an Indian village, situated on the face of a steep rock, containing about one hundred and fifty of the natives, some few of whom had visited our party in their way up the canal, and now many came off in the most civil and friendly manner, with a plentiful supply of fresh herrings and other fish, which they bartered in a fair and honest way for nails. These were of greater value amongst them, than any other articles our people had to offer.

… I repaired to the village, and found it pleasantly situated on a sloping hill, above the banks of a fine fresh—water rivulet, discharging itself into a small creek or cove. It was exposed to a southern aspect, whilst higher hills behind, covered with lofty pines, sheltered it completely from the northern winds. The houses, in number thirty-four, were arranged in regular streets; the larger ones were habitations of the principal people, who had them decorated with paintings and other ornaments, forming various figures, apparently the rude designs of fancy; though it is by no means improbable, they might annex some meaning to the figures they described, too remote, or hieroglyphical, for our comprehension.

On going on shore, we found a small canoe with three of the natives, who were employed in taking salmon, which were in great abundance, up a very fine run of fresh water that flowed into the cove. Some of these fish were purchased with looking glasses and other trinkets. They were small, insipid, of a very inferior kind, and partaking in no degree of the flavor of European salmon.

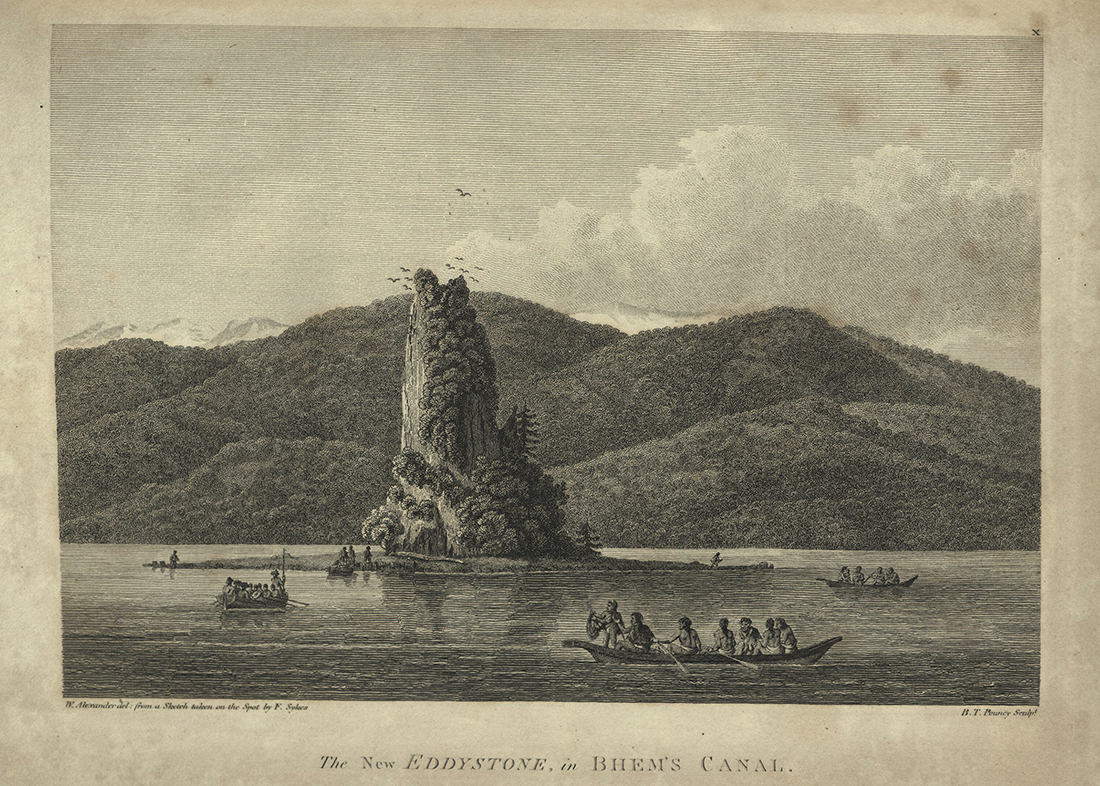

On the base of this singular rock, which, from its resemblance to the Light House rock off Plymouth, I called the New Eddystone, we stopped to breakfast, and whilst we were thus engaged, three small canoes, with about a dozen of the natives, landed and approached us unarmed, and with the utmost good humour accepted such presents as were offered to them, making signs, in return, that they had brought nothing to dispose of, but inviting us in the most pressing manner to their habitations; where they gave us to understand, they had fish skins, and other things in great abundance, to barter for our commodities, amongst which, blue cloth seemed to be the most esteemed.

My people could not, at this time, refrain from expressions of real concern, that they were obliged to return without reaching the sea: indeed the hope of attaining this object encouraged them to bear, without repining, the hardships of our unremitting voyage. For some time past their spirits were animated by the expectation that another day would bring them to the Mer d’ouest: and even in our present situation they declared their readiness to follow me wherever I should be pleased to lead them.

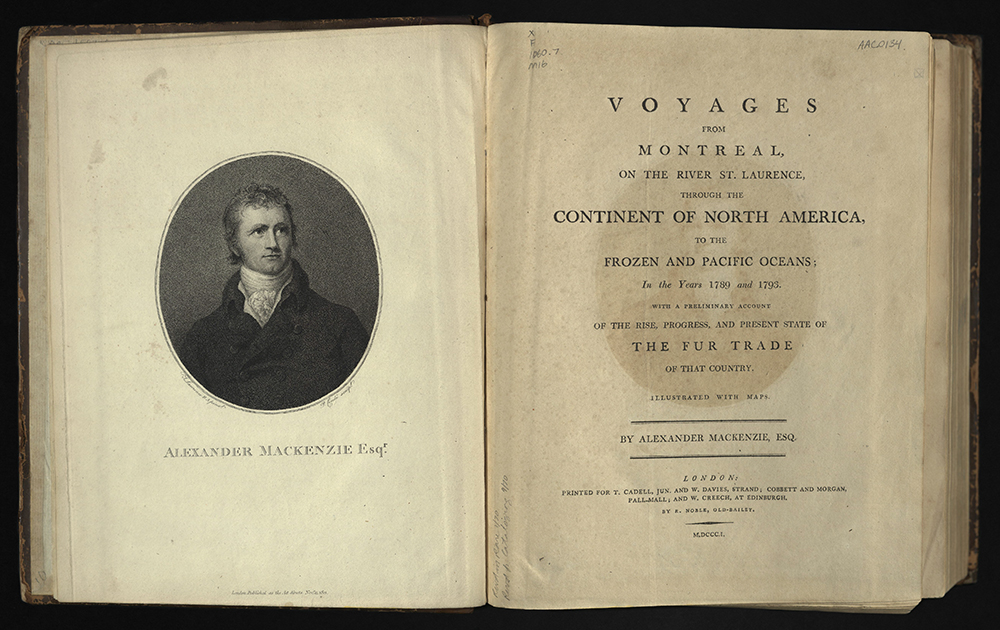

VOYAGES FROM MONTREAL ...

Sir Alexander Mackenzie (1763-1820)

London: T. Cadell, jun. and W. Davies: 1801

First edition

F1060.7 M16

In 1789, Alexander MacKenzie, a Scotsman in the fur trade out of Montreal, canoed nearly three thousand miles from Fort Chipewyan, in present-day Alberta, north and west along the river that now bears his name, to the shores of the Arctic Ocean and back again. In 1793, again leaving from Fort Chipewyan, he traveled the Peace River west to the Continental Divide, reaching it a month after his journey began, and continued on foot to the Pacific, arriving thirteen days later, on July 22, 1793, thus becoming the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean by crossing the Rocky Mountains.

Using his telescope, Mackenzie spotted Jupiter and noted the time when the moons Io and Ganymede disappeared behind the planet. With this sighting, tables showing the times of the same events from Greenwich, and his sextant, Mackenzie established the latitude and longitude of his place. The British had their claim on the northwestern empire.

Back at Fort Chipewyan, Mackenzie fell into a depression and struggled to prepare his journal for publication. He left Canada and never returned. His account was probably ghostwritten – Mackenzie was not educated enough to write a publishable report. In the account of his Canadian overland journey to the Pacific, Mackenzie highlighted the stakes for whichever nation first established settlements on the Pacific Coast and the Columbia River. That nation, Mackenzie wrote, would possess “the entire command of the fur trade of North America…and the markets of the four quarters of the globe.” Whichever country first established settlements at the Columbia River would control a vast empire.

Mackenzie described his journey as “long, painful and perilous,” but he also wrote “The way to the Pacific lay open and easy.” President Thomas Jefferson immediately ordered a copy of this book, which he and Meriwether Lewis devoured. Jefferson read Mackenzie’s warnings to his British countrymen about the urgent necessity of controlling the mouth of the Columbia and the Pacific coast. News of Mackenzie’s achievement, and his recommendation that the British fur trade set up shop at the mouth of the Columbia River, spurred Jefferson to organize a response that would affirm U.S. territorial rights in the Pacific Northwest. That response grew into the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-06. Meriwether Lewis urged President Jefferson to create a seaport on the Pacific Rim as an outlet to China for furs from the western sector of North America and accepted his own challenge without hesitation.

Aside from plotting one way to cross the continent, Mackenzie’s report was remarkably sparse: he collected few specimens, made few descriptions, advanced nothing of worth regarding plants, animals, minerals, or native inhabitants of the country he crossed.

Language cannot express the gaiety of my heart, when I once more beheld the standard of my country waved aloft: -- “All hail" cried I, "the ever sacred name of country, in which is embraced the kindred, friends, and every other tie which is dear to the soul of man!!"

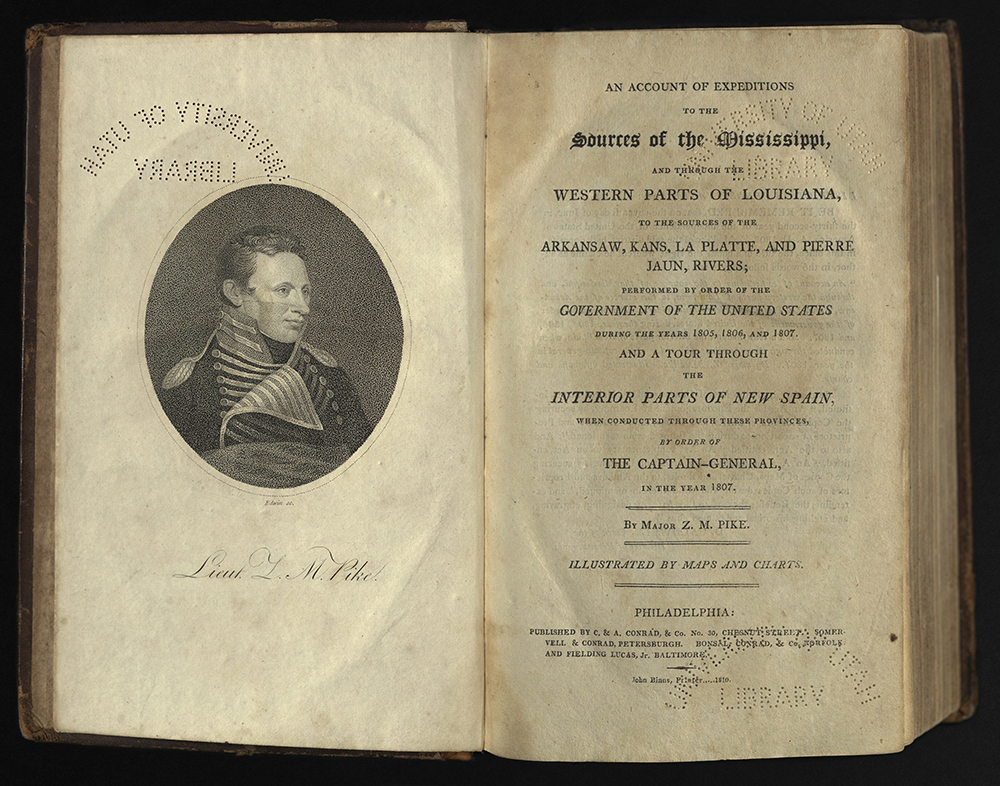

AN ACCOUNT OF EXPEDITIONS TO THE SOURCES ...

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (1779-1813)

Philadelphia: Published by C. & Z. Conrad, Somervell & Conrad, Peterburgh, Bonsal, Conrad, Norfolk, and Fielding Lucas, jr., Baltimore. John Binns, printer, 1810

First edition

F592 P63

This is a report of the first United States government expedition to the Southwest, and includes an account of exploration of the headwaters of the Arkansas and Red rivers, the sources of the Mississippi River, and the Spanish settlements in New Mexico.

Zebulon Pike was born in New Jersey, where his father, a career military officer, fought the British under George Washington. As the son of a soldier, Pike grew up in posts all across the Ohio frontier before joining the service himself at the age of fifteen. He was made a lieutenant at the age of twenty, in 1799. He was at Kaskaskia in 1803, when Meriwether Lewis came through to recruit for his so-called “Corps of Discovery.”

In 1805, Pike was assigned to conduct a reconnaissance of the upper Mississippi region, where it was reported that English fur traders from Canada were illegally working on American soil. He was ordered to purchase sites from the Indians for further military posts and to bring a few influential chiefs back to St. Louis for talks.

Pike headed north on August 9, 1805, in a seventy-foot keelboat. In September he reached what is now Minneapolis, Minnesota. After wintering further upriver and contacting British traders, he met with Dakota Indians. The expedition returned to St. Louis on April 30, 1806, where Pike remained for only a few weeks. The trip was only moderately successful as a mission to the tribes, but Pike was able to convey important geographical information to President Jefferson and other Washington officials.

Pike’s second expedition was meant to explore the headwaters of the Arkansas River, then proceed south and descend the Red River from its source. He was sent to reconnoiter the Spanish borderlands in order to ascertain the southern limits of the recent Louisiana Purchase, in part looking for suitable places for military and commercial sites.

Political intrigue among Spain, Britain, and the United States, including espionage, made the expedition even more dangerous than it already was. Unlike other expeditions commissioned by President Jefferson, Pike traveled under direct orders from General James Wilkinson, governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory and sometime secret agent for the Spanish.

Pike left for his travels south on July 15, 1806 with twenty-three men. They headed west up the Missouri River to Osage country at the border of modern Kansas and then, led by Osage guides, reached a Pawnee village near the border of Kansas and Nebraska. From there they turned south to the Arkansas River, which they followed west, reaching present-day Pueblo, Colorado on November 23 and the South Platte on December 12. They wintered near present-day Alamosa, Colorado. On February 26, 1807, they were captured by Spanish troops.

The expedition, was, in fact, on Spanish lands, as per the instruction of Wilkinson. The Spanish confiscated Pike’s notes and carried the party through Albuquerque and El Paso, arriving in Chihuahua, Mexico. The authorities there, wanting to avoid an international incident, ordered Pike and his troops be returned to the United States. They traveled back through San Antonio, Texas to Natchitoches, Louisiana. Because of political tensions, no American would explore the Southwest again until Stephen Long’s expedition in 1820.

Pike wrote his account from memory. His book is often disorganized, vague or incorrect about exact locations, dates, and events. Publisher Z. Conrad proposed the book in 1808, and began soliciting subscribers in January 1809. The book was not a financial success. The publisher went bankrupt and Pike received no royalties. Still, it was published in London in 1811, Paris in 1812, Amsterdam in 1812, Weimar in 1813 and Vienna in 1826. The maps in this book were the first to exhibit a geographic knowledge of the Southwest based on first-hand exploration.

Pike’s account asserted the weakness of the Spanish authority in Santa Fe, and the profitability of trading with Mexico, stirring businessmen and politicians to expand into Texas. After the expedition, Pike was promoted to major in 1808. During the War of 1812, he was made a colonel and then a general. While commanding an attack on York (present-day Toronto), Pike was killed when the enemy detonated hidden explosives under his advancing troops.

Most of Pike’s notes were returned to the United States State Department in 1910. Illustrated with a stipple-engraved India paper proof portrait frontispiece by Edwin; 6 engraved maps, 5 of which are folding; and 3 folding letterpress tables.

We had not gone far from this village when the fog cleared off, and we enjoyed the delightful prospect of the ocean, the object of all our labours, the reward of all our anxieties. This cheering view exhilarated the spirits of all the party, who were still more delighted on hearing the distant roar of breakers.

HISTORY OF THE EXPEDITION UNDER THE COMMAND OF CAPTAINS LEWIS AND CLARK ...

Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809)

Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep; New York: A.H. Inskeep, 1814

First edition

F592.4 1814

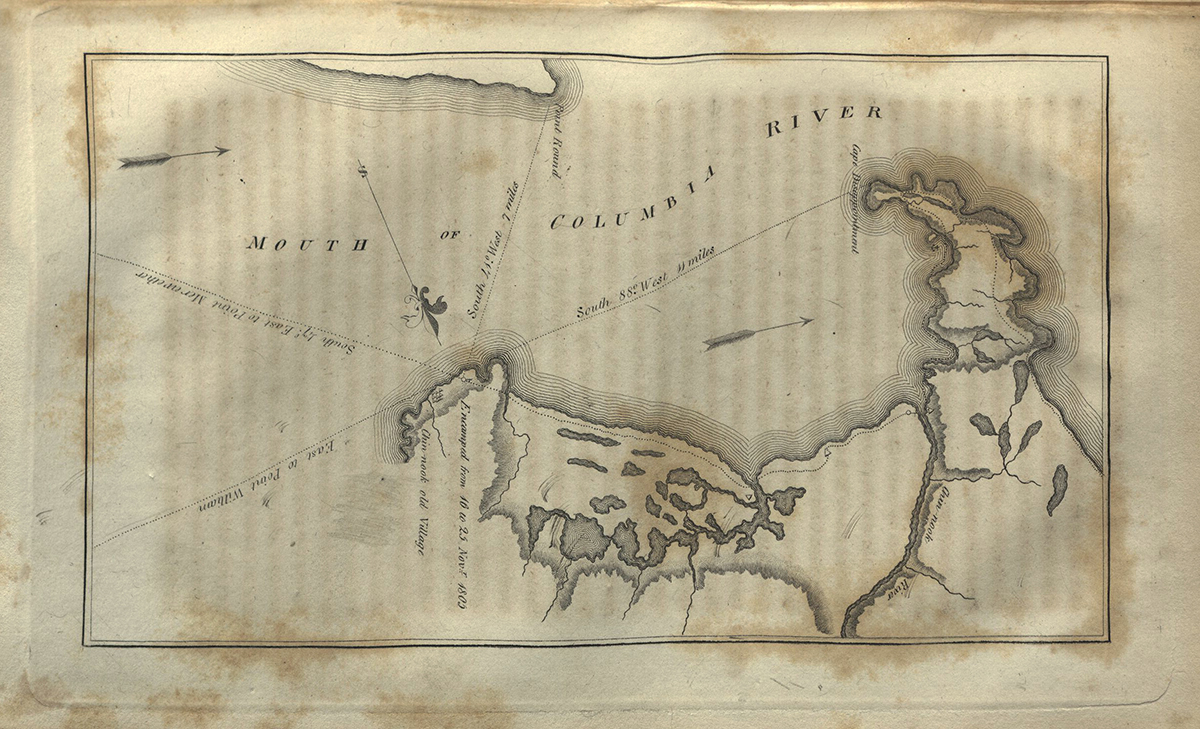

Meriwether Lewis’s and William Clark’s exploration of the American west was one of the most important accomplishments of a young United States. Lewis, Clark and their Corps of Discovery made the first overland trip from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast and back. These were the first white men to enter present-day Idaho, Washington, and Oregon by land. Traveling north, they followed the Missouri River from its confluence at the Mississippi River to its source, turned west and, after crossing the Rocky Mountains, explored the Columbia River from its source to the Pacific Ocean.

Lewis wrote a narrative of this expedition and Clark contributed the maps. This published account contains information on the geography and ethnography of the area Lewis, Clark and their party saw, describing the government-funded expedition to explore the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase.

The expedition took place between 1804 and 1806. In total, the expedition traveled nearly eight thousand miles in a little more than twenty-eight months. On its way home, the Corps of Discovery met with a four-man trading party which had news that Zebulon Pike had left St. Louis to explore the Red and Arkansas Rivers.

They returned with the first reliable information about much of the area, made contact with indigenous peoples as a prelude to fur-trading possibilities, and increased the amount of geographical information regarding the lower North American continent. Clark’s map of the West accurately depicts the trans-Mississippi for the first time.

Although Lewis and Clark completed their expedition in September, 1806, this account, which is an edited version of the journals they maintained during their travels, was not published until February 20, 1814, five years after Lewis’s death. Only a portion of Lewis and Clark’s accounts of their epic expedition west appeared in print. After Meriwether Lewis’ mysterious death (probably suicide), the task of editing their journals fell to William Clark who, in turn, asked Philadelphia lawyer Nicholas Biddle to complete the job. When the story was finally published more than fourteen hundred copies were distributed. The book sold for six dollars.

Lewis often wrote personal reflections of what he experienced while recording his scientific observations. His writing had a raw quality that evoked the danger and high adventure of the trip across an unknown wilderness. His report had a profound effect upon the United States. A much more aggressive westward vision quickly outstripped President Jefferson’s modest notion of continued agrarian opportunities with a little commerce thrown in for good measure.

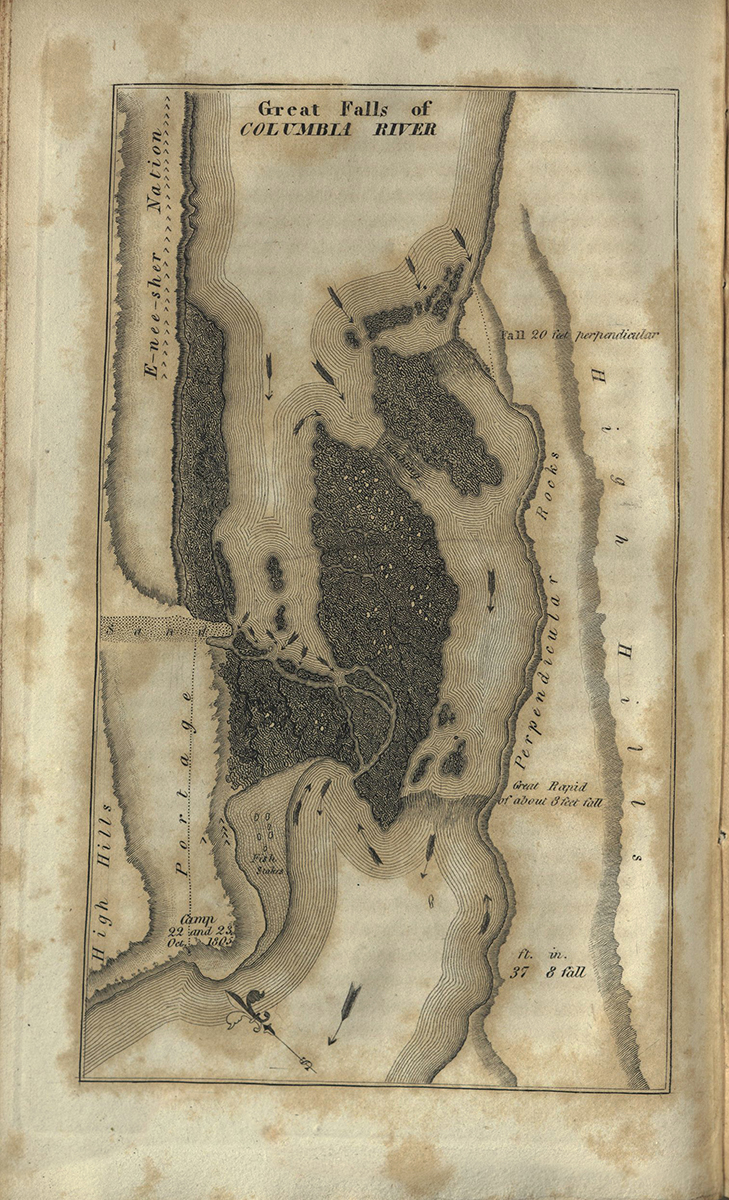

Two miles below we came to seventeen huts on the right side of the river, situated at the commencement of the pitch which includes the great falls. Here we halted, and immediately on landing walked down, accompanied by an old Indian from the huts, in order to examine the falls, and ascertain on which side we could make a portage most easily.

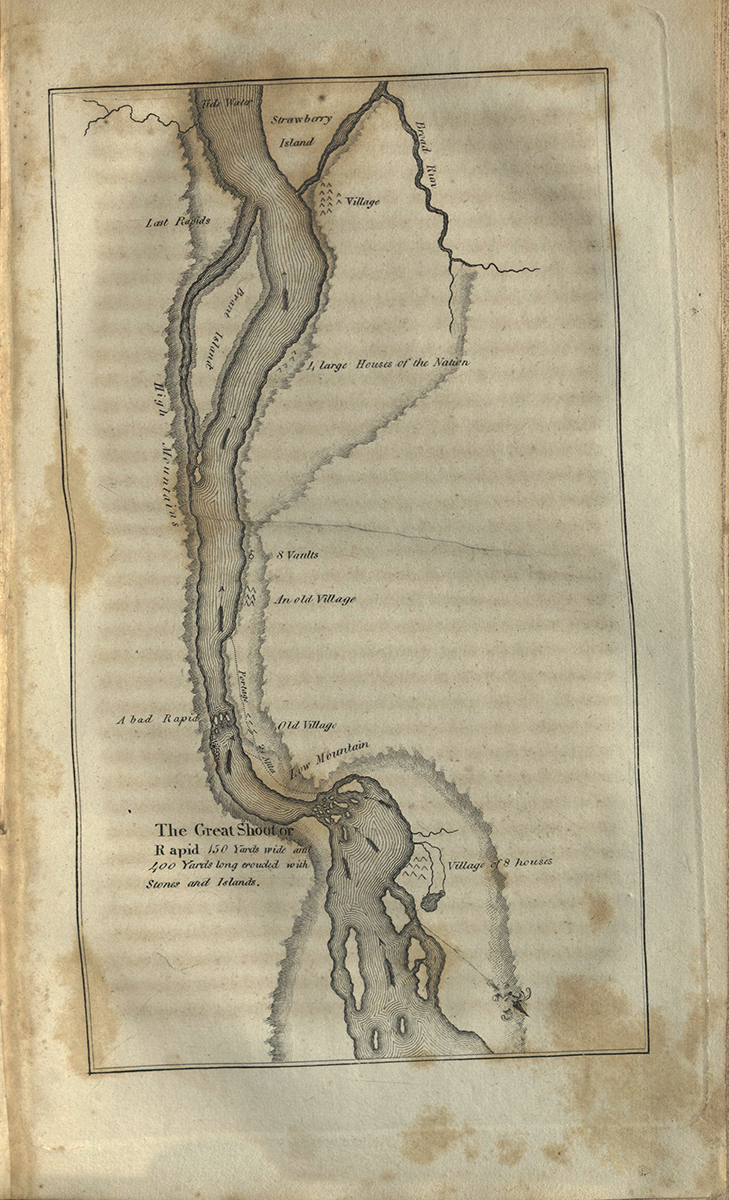

Within this narrow limit it runs for the distance of four hundred yards with great rapidity, swelling over the rocks with a fall of about twenty feet: it then widens to two hundred paces, and the current for a short distance becomes gentle; but at the distance of a mile and a half, opposite to the old village… it is obstructed by a very bad rapid, where the waves are unusually, high, the river being confined between large rocks, many of which are at the surface of the water.

Robins, (Tursus migratorius.) which we had not seen since we left the Missouri, here occurred in great numbers.

ACCOUNT OF AN EXPEDITION FROM PITTSBURGH TO THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS ...

James Edwin (1797-1861)

Philadelphia: H. C. Carey and I. Lea, (1822-23)

First edition

F592 J3

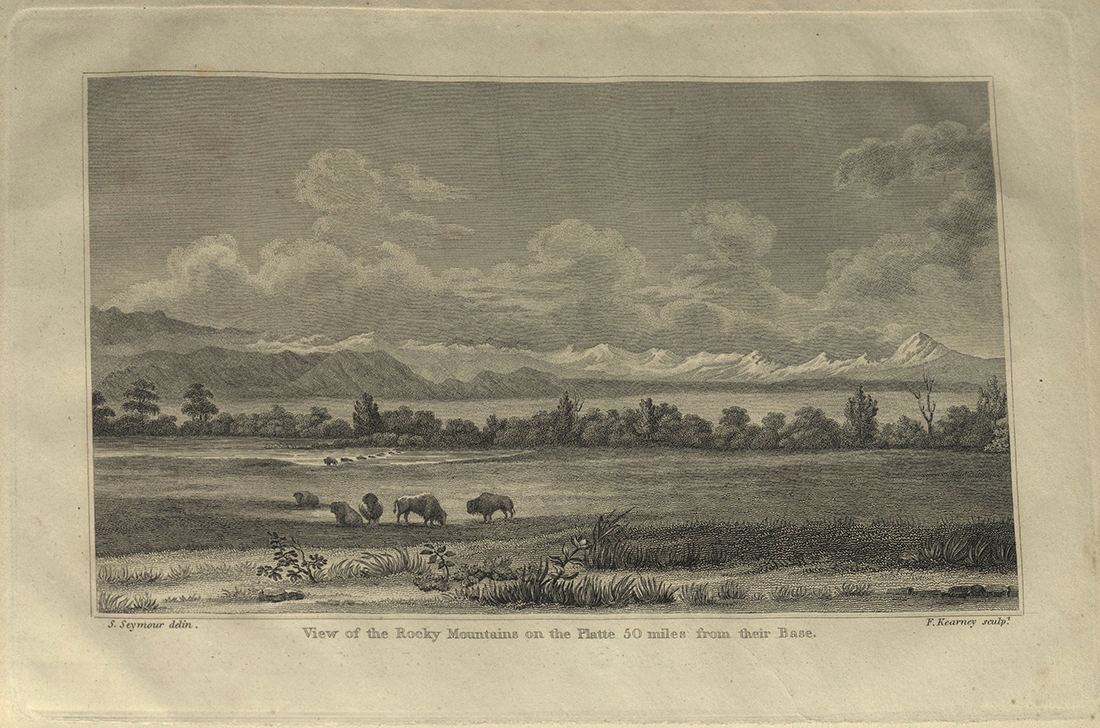

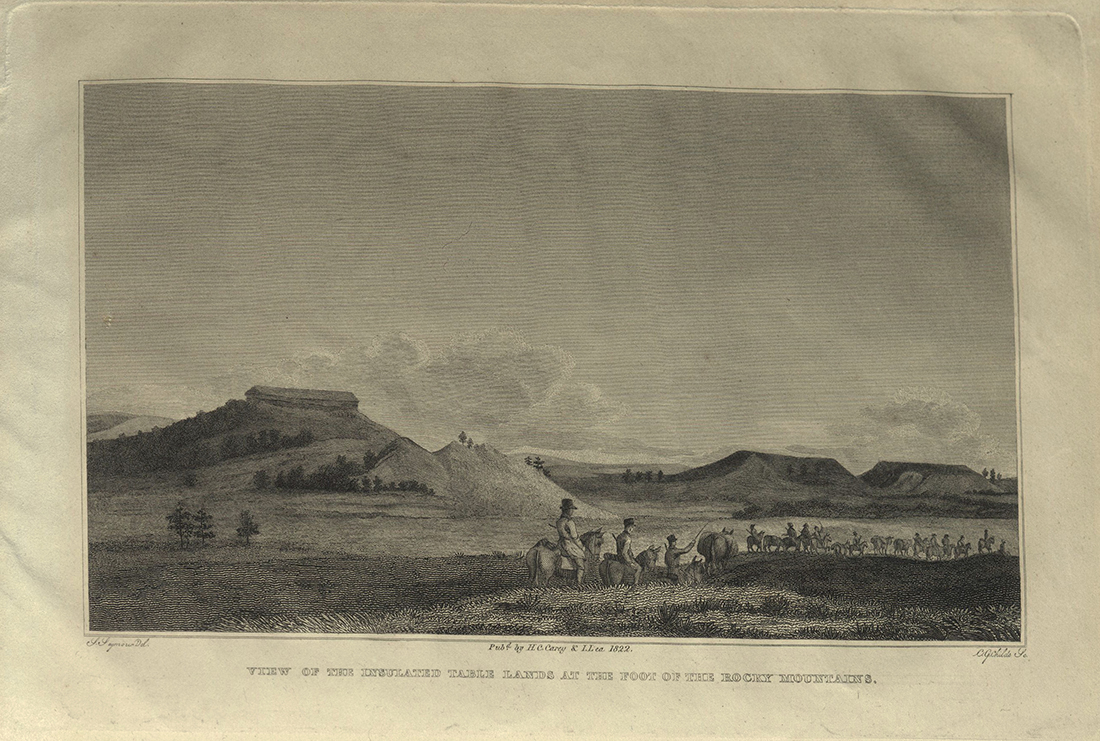

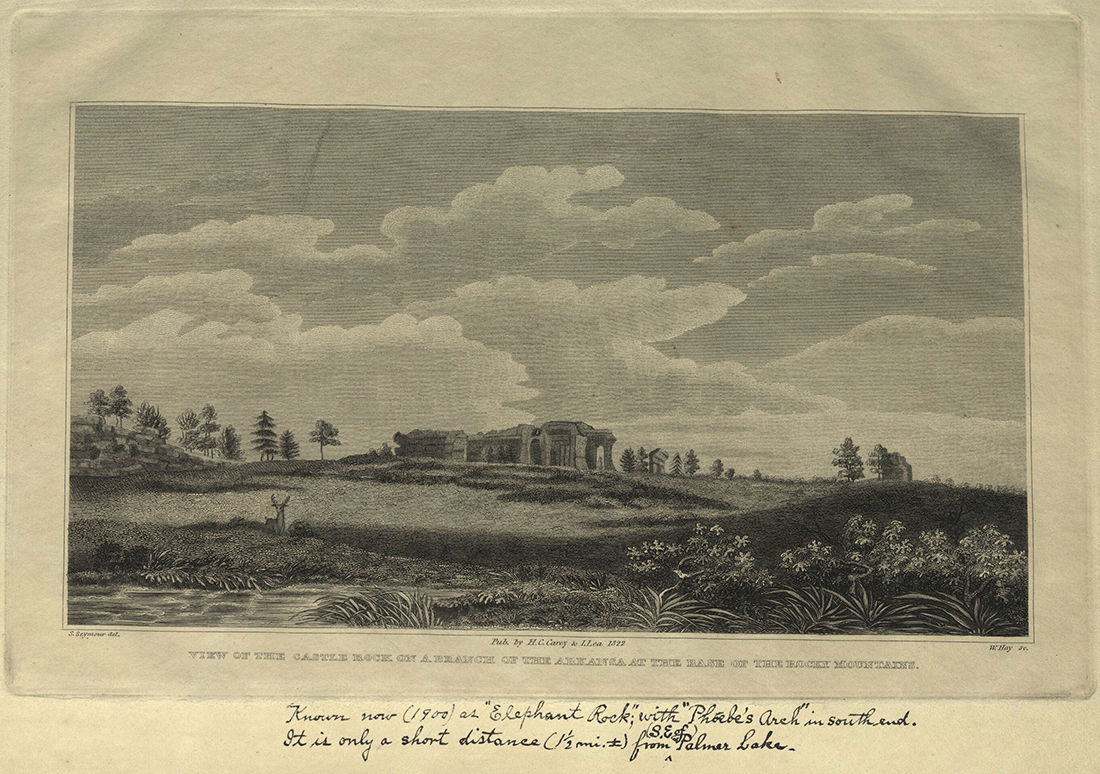

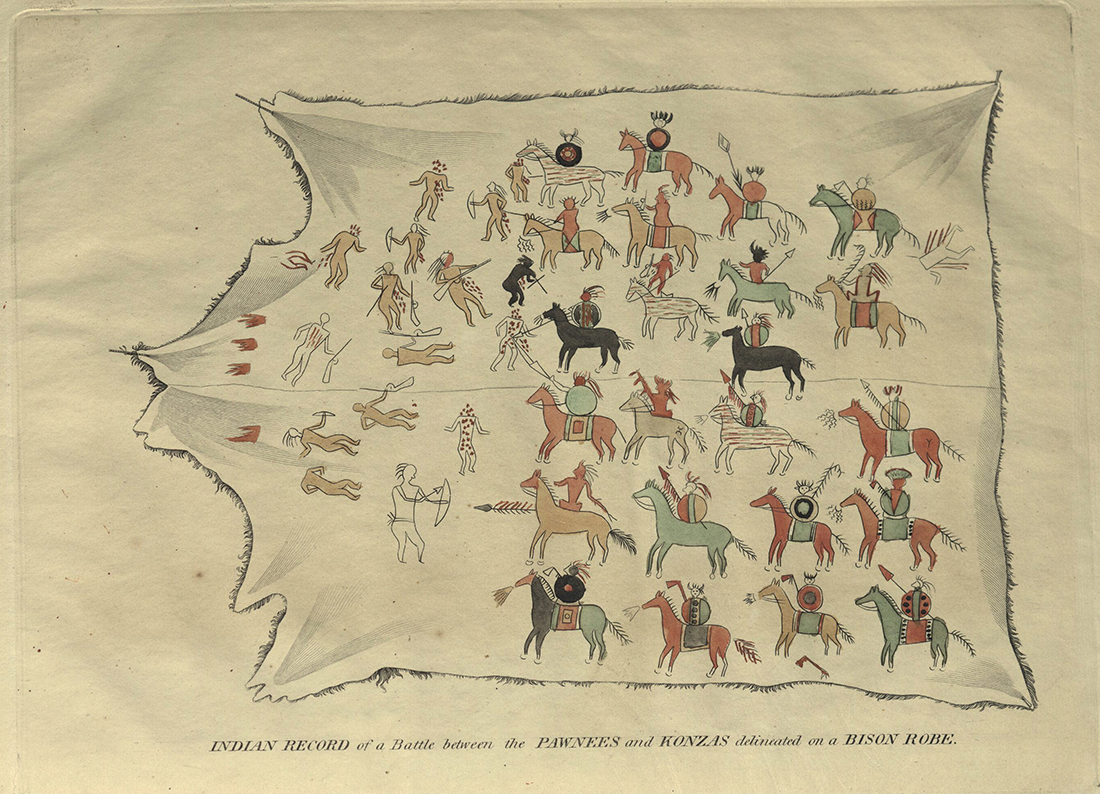

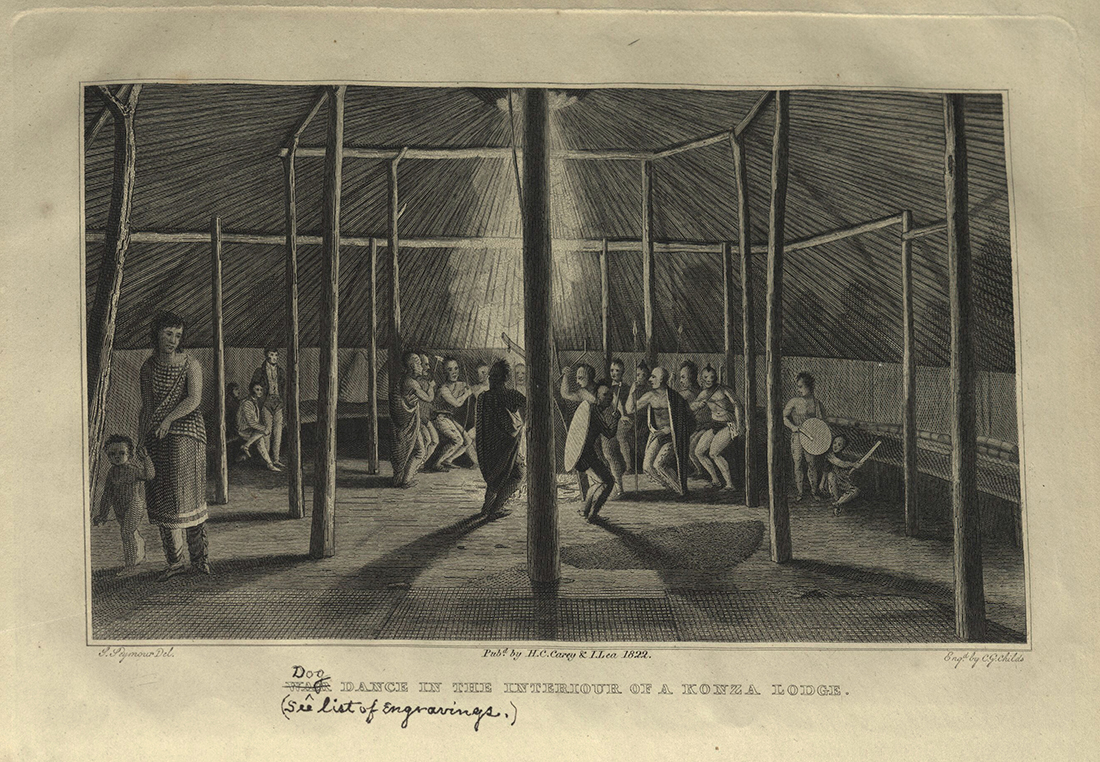

Edwin James was born in Vermont. When he was 23, he was appointed botanist, geologist, and surgeon for the expedition commanded by Major Stephen H. Long. Following the War of 1812, Major Long became a proponent of government-sponsored exploration of the West. He began this expedition under the order of John C. Calhoun, then Secretary of War. The Long expedition was the third major exploration of the trans-Mississippi West, following those of Lewis and Clark and Pike. It was the first expedition accompanied by artists.

James’s compilation of records of the 1819-1820 exploration of the American northwest contributed valuable information regarding the natural landscape, native peoples and wildlife of a heretofore largely unexplored region by the United States.

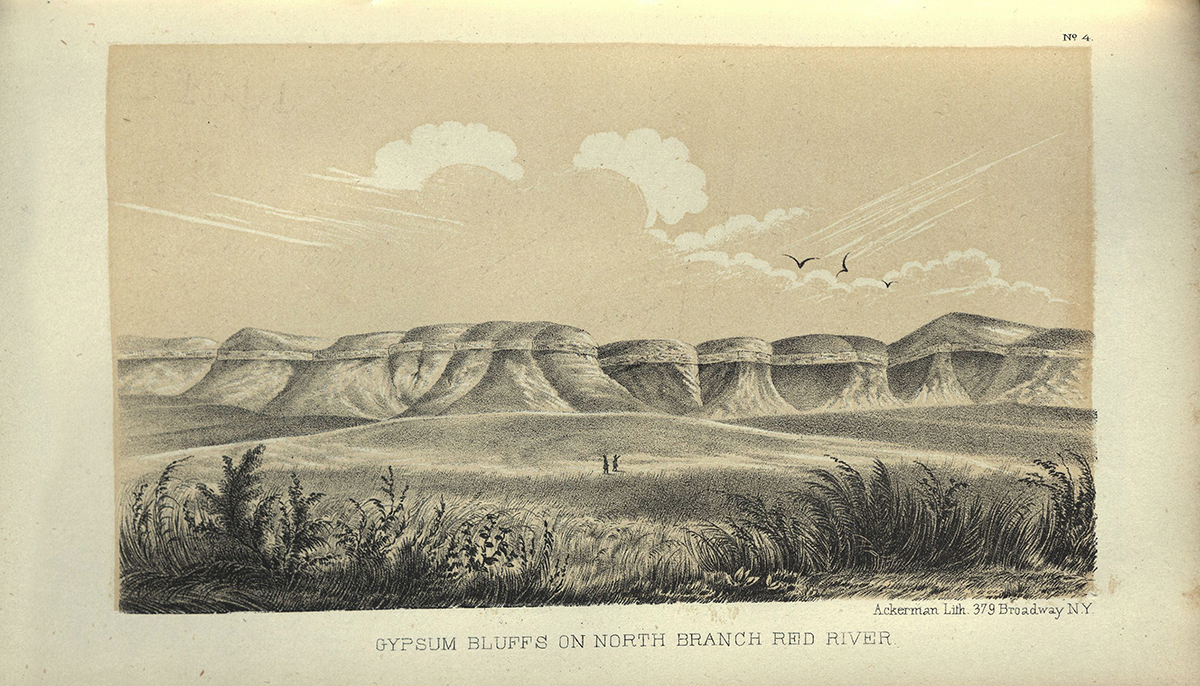

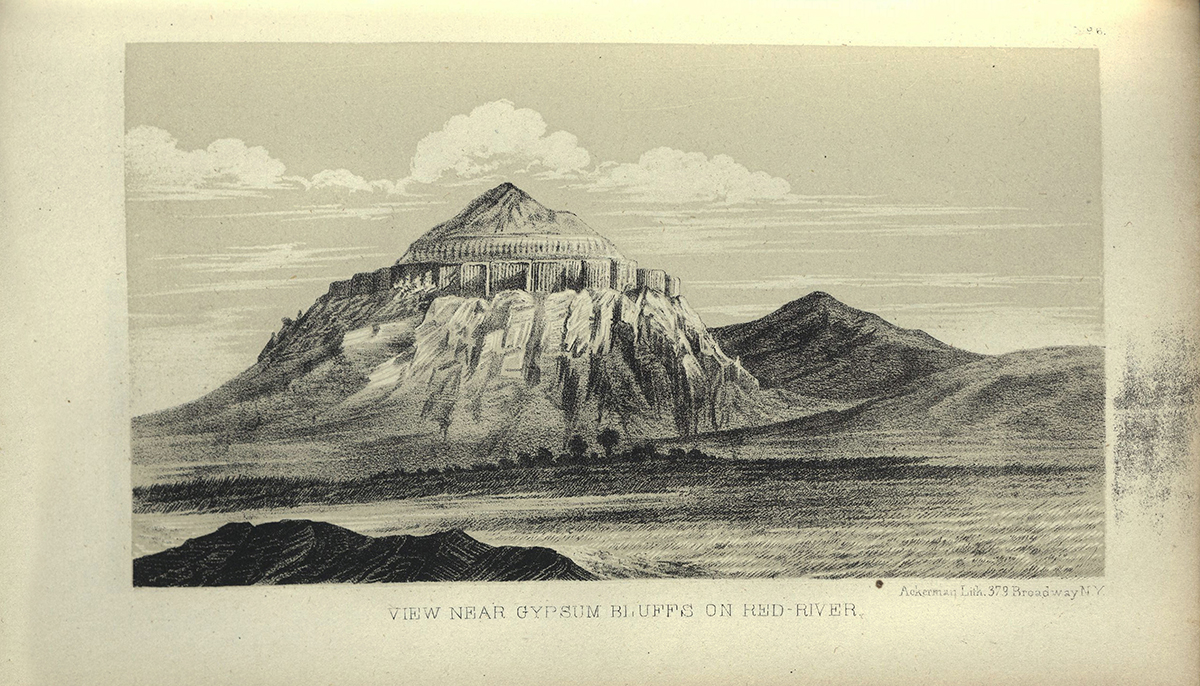

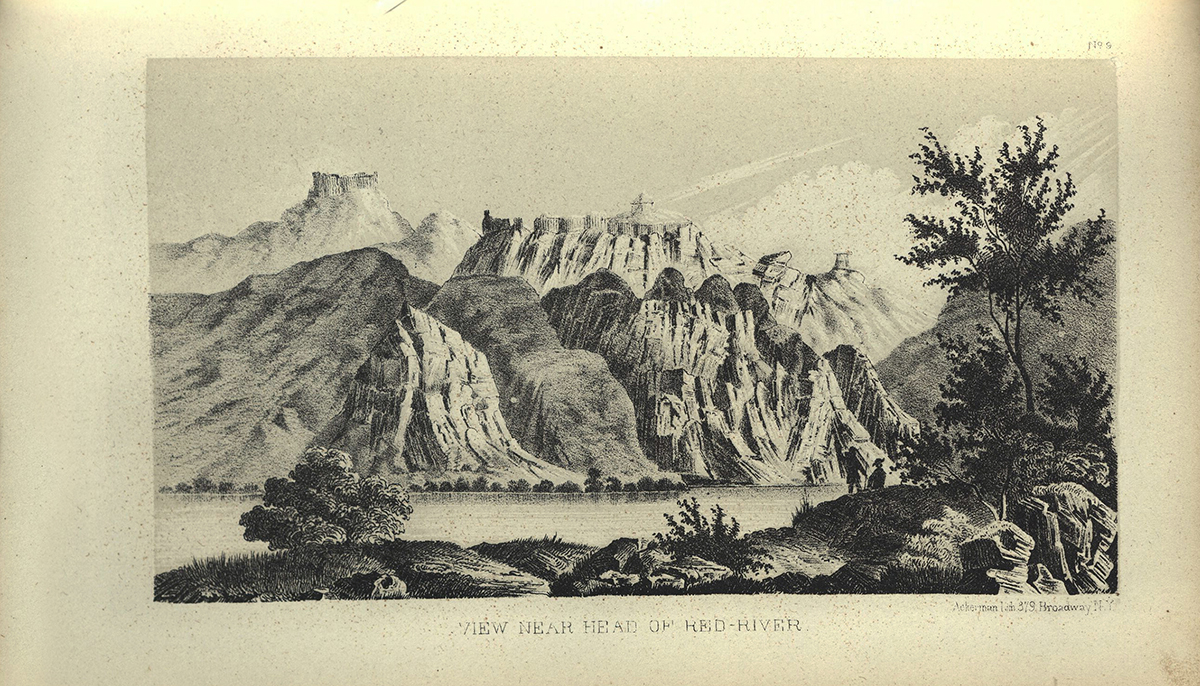

Major Long was commissioned to ascend the Platte River and explore the headwaters of both the Red River and the Arkansas River. The expedition followed the Platte River to the South Fork to the Colorado Rockies, where it found and named Long’s Peak. On July 5, 1820, they reached present-day Denver and on July 12, Colorado Springs, from where three of the party members, including James, climbed Pike’s Peak, the first men known to do so.

The party continued south to the upper Arkansas River, where Long divided the group: one to continue the exploration of the Arkansas; the other, which included Long and James, to explore the Red River. In early august this second party followed the Canadian River, mistaking it for the Red. This mistake led the group into New Mexico and the Texas panhandle., where they encountered a party of Kiowa Apache, the first recorded meeting between Anglo-Americans and members of this people. The group continued through Oklahoma and rejoined the first group at Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Neither the source of the Arkansas nor the Red River were found, but Long’s expedition travelled farther than Pike and blazed trails that would later be followed by John C. Fremont and John Wesley Powell.

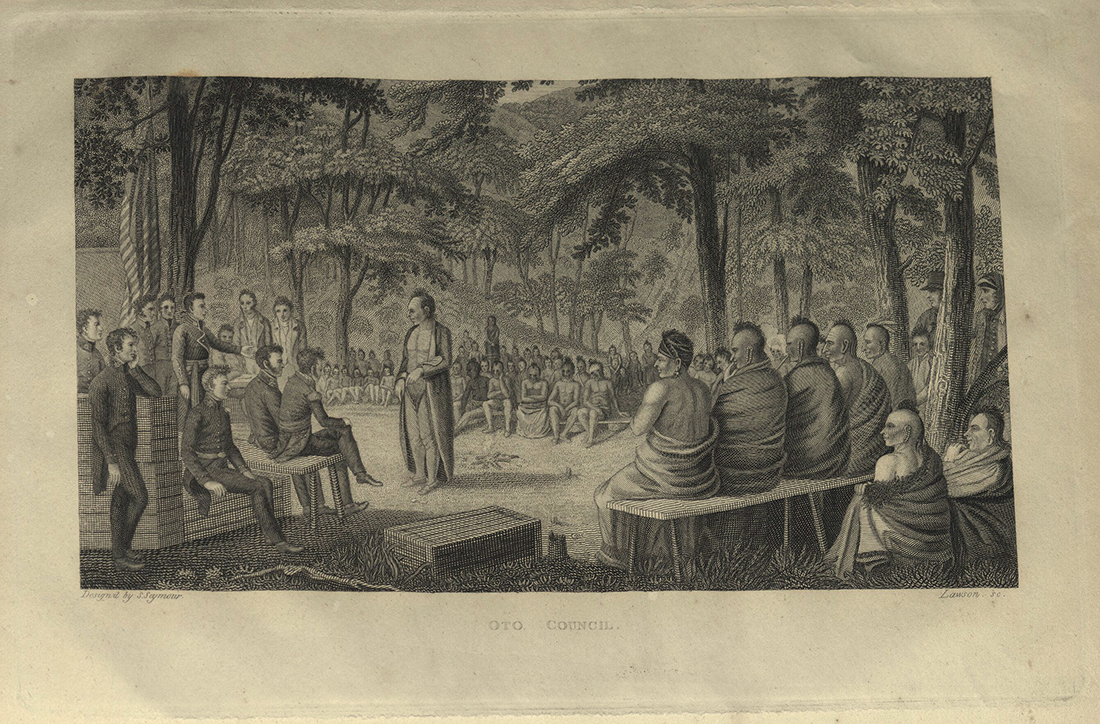

James compiled this account from notations in his journal, Major Long’s notes, and the observations by naturalist Thomas Say. Titian Peale was the draughtsman and assistant naturalist on the expedition. Samuel Seymour was the landscape artist.

Account was to be published simultaneously in Philadelphia and London, but the two editions differ substantially. Review of contemporary correspondence and periodicals indicates the Philadelphia was available for sale on 31 December 1822, whereas the London edition was not available until late February 1823. The Philadelphia edition is the authority for most of the new taxonomic contributions in the work.

After the expedition, James studied Native American languages and translated the New Testament into Ojibwa. He worked as a newspaper editor in Albany, New York, and then settled in Iowa where he ran a station on the Underground Railroad.

Appendices in this work include astronomical and meteorological tables and Native American vocabularies. Plates depict Oto Indians, views of the Plains and buffalo.

The accompanying atlas contains the first maps providing detail of the Central Plains, with a note: “The Great American Desert is frequented by roving bands of Indians who have no fixed places of residence but roam from place to place in quest of game.”

We were overshadowed by lofty trees, with straight, smooth trunks, like stately columns; and as the glancing rays of the sun shone through the transparent leaves, tinted with the many-colored hues of autumn, I was reminded of the effect of sunshine among the stained windows and clustering columns of a Gothic cathedral. Indeed there is a grandeur and solemnity in our spacious forests of the West, that awaken in me the same feeling I have experienced in those vast and venerable piles, and the sound of the wind sweeping through them, supplies occasionally the deep breathings of the organ.

A TOUR OF THE PRAIRIES

Washington Irving (1783-1859)

London: J. Murray, 1835

First edition

F697 I743 1835

In 1832, Washington Irving, America’s literary superstar, returned to the United States after seventeen years abroad. Almost immediately he joined an expedition exploring Osage and Pawnee country – a territory still mostly uncharted by Americans – in what is now Oklahoma. Few white men had set foot in the region and fewer still had written about it.

Irving’s reputation for patriotism had been suffering because of his long time abroad, when he met the newly appointed Indian Commissioner, Henry L. Ellsworth, on a steamboat and accepted the opportunity to join his expedition.

Irving found the whole adventure invigorating: sleeping under the stars was for him a tranquil experience. He embraced Pawnee culture. He kept a daily account of his excursion. When he returned home, he turned his notes into this entertaining work, describing the terrain of the giant rivers and golden plains he had seen and vividly depicting the lives of Native Americans. The affectionate work was hugely successful. It is from this work that a lasting character of the American West was painted: the hardy fur-trapper with trusty rifle, an intrepid bride, scorn for the sweets of civilization and a fierce pride of independence; and the wild plains warrior invading neighboring tribes and ever steeped in ancient lore.

The narrator of this work is Geoffrey Crayon, already familiar to Irving’s fans as an unabashed Anglophile and Hispanophile. Published in the United States one month after the London edition, the work was also published in Paris that same year.

I have seen beautiful and enchanting sceneries depicted by the artist, but never any thing to equal the work of rude nature in those prairies. In the spring of the year when the grass is green and the blossoms fresh, they present an appearance, which for beauty and charms, is beyond the art of man to depict.

NARRATIVE OF THE ADVENTURES OF ZENAS LEONARD

Zenas Leonard (1809-1857)

Clearfield, Pa: D. W. Moore, 1839

First edition

F592 L36 1839

Zenas Leonard’s memoirs of his travels were written, he said, at the request of friends. In order to avoid having to repeat his story over and over again, he decided to write his Narrative. It was published by a small press in his home town. The adventurous Leonard left St. Louis on April 24, 1831 heading west to make his fortune trapping for furs and trading with Indians.

Leonard began his journey as a clerk for a fur trading firm that failed. He remained in the Rocky Mountains as a free trapper. In 1833, he joined the party of Captain Bonneville. With this party, he crossed the Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada to California.

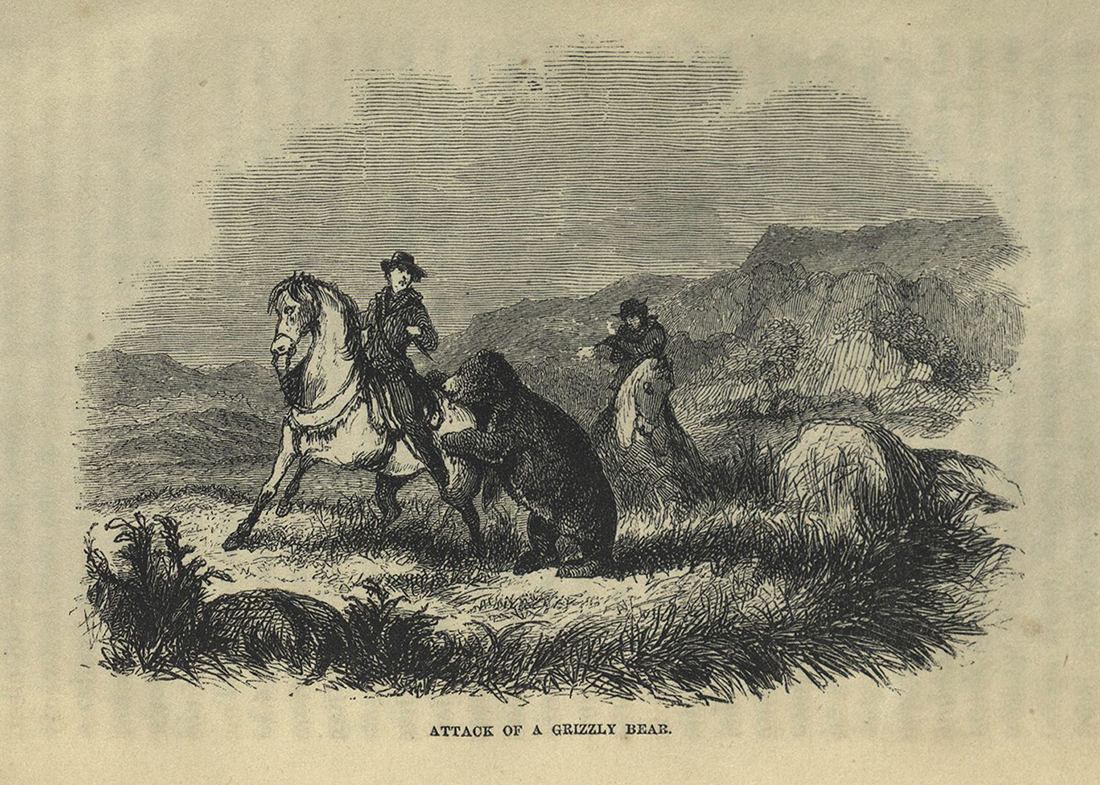

From the beginning Leonard was plagued with misfortune: starvation, attack by a grizzly bear, and encounters with hostile Blackfoot Indians. Nothing was heard of him for five years, until he finally reached the Pacific coast, just south of San Francisco. He flagged down a passing ship from Boston which gave him passage back home. No fortune was made, but his Narrative is an honest and compelling account of his transcontinental trek.

Portions of Leonard’s narrative were published in the Clearfield Pioneer & Banner in 1835 and 1836. The publisher of the newspaper then printed this separate, complete edition, announcing in the preface, “Our author kept a minute journal of every incident that occurred, but unfortunately, a part of his narrative was stolen from him by hostile Indians; still, however, he was enabled to replace the most important events, by having access to the journal kept by the commander of the expedition. His character for candour and truth, among his acquaintances, we have never suspected… At all events, in its perusal, the reader will encounter no improbabilities, much less impossibilities: -- hence it is but reasonable to suppose that in traversing such a wilderness as lays west of the Rocky Mountains, such hardships, privations and dangers as those described by Mr. Leonard, must necessarily be encountered.”

We have amongst our men, a great variety of dispositions. Some who have not been accustomed to the kind of life they are to lead in future, look forward to it with eager delight, and talk of stirring incidents and hair-breadth ‘scapes. Others who are more experienced seem to be as easy and unconcerned about it as a citizen would be in contemplating a drive of a few miles into the country. Some have evidently been reared in the shade, and not accustomed to hardships, but the majority are strong, able-bodied men, and many are almost as rough as the grizzly bears, of their feats upon which they are fond of boasting.

NARRATIVE OF A JOURNEY ACROSS THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS ...

John K. Townsend (b. 1809)

Philadelphia: Boston: H. Perkins, 1839

F592 T68

John Kirk Townsend’s Narrative is based on a journal he kept while traveling to Oregon with Nathaniel Wyeth’s 1834 expedition, the two years he spent in Oregon, and his travels back to the east coast of the United states via Hawaii and Chile.

Born into a Philadelphia Quaker family, Townsend’s siblings were active in medicine and science. Three of his brothers were dentists, one was a philanthropist interested in prison reform. One sister wrote a book on insects for children, another wrote a history of England in verse.

John attended a boarding school where entomologist Thomas Say had also attended. Thomas Say later traveled with Edwin James on his western expedition. Townsend developed his skill at taxidermy and began collecting the birds of West Chester County, admired by John James Audubon.

Nathaniel Wyeth was a Massachusetts ice merchant who dreamed of establishing a fur trading company on the west coast. John Nuttall, a botanist, invited Townsend to join the expedition.

An appendix in this book cites Audubon’s Birds of America in its description of specimens procured on the expedition. Some of the skins brought back from the west by John Kirk Townsend and John Nuttall were given to Audubon by the Philadelphia Academy. Nuttall personally gave Audubon a few of the specimens he had gathered on the expedition.

Rare Books copy inscribed by the author to an Edwin Willcox.

Amidst the multiplicity of books which are, in this enlightened age, flooding the world, I feel it is my duty, as early as possible, to beg pardon for making a book at all; and in the next (if my readers should become so much interested in my narrations, as to censure me for the brevity of the work) to take some considerable credit for not having trespassed too long upon their time and patience.

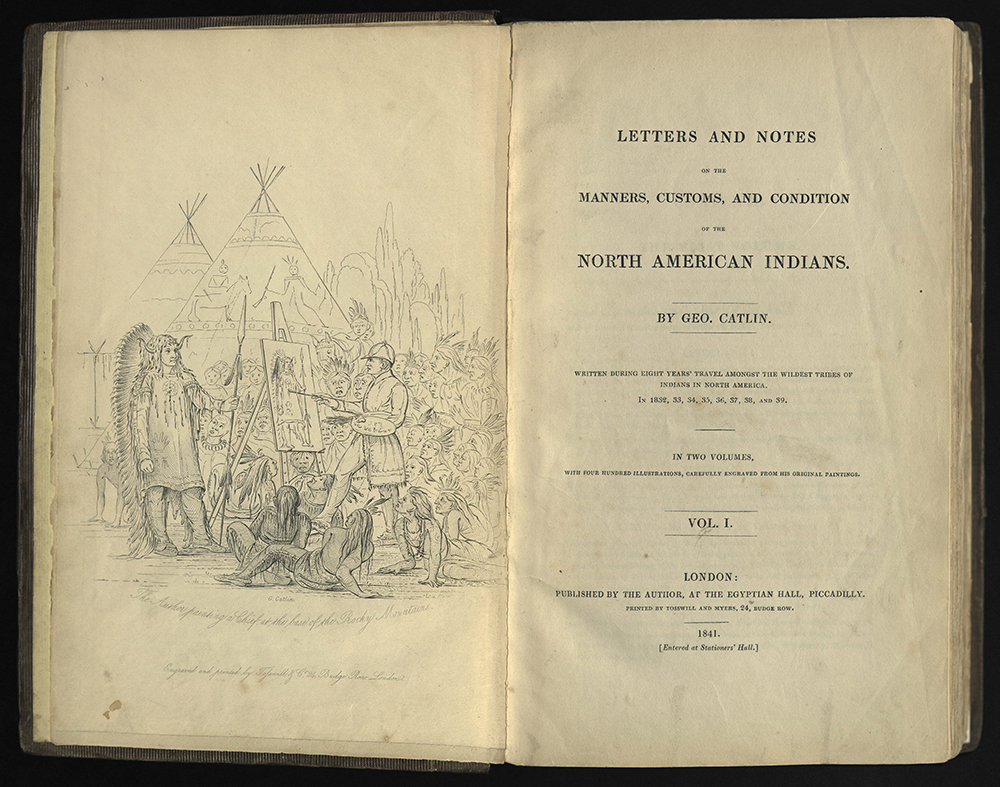

LETTERS AND NOTES ON THE MANNERS, CUSTOMS ...

George Catlin (1796-1872)

London: Pub. by the author, printed by Tosswill and Myers, 1841

First edition

E77 C38

Artist George Catlin traveled throughout the American West, visiting forty-eight Indian tribes, painting their portraits, and recording their games, dances, funerals, religious ceremonies, buffalo hunts, dress, and weapons. Catlin traveled for six years, documenting southern and western American Indians.

In 1832, Catlin headed upriver, on the first steamboat to ascend the Missouri, to Fort Union, near the mouth of the Yellowstone. His eighteen-hundred-mile journey introduced him to the Blackfoot, Crow, Lakota, and the Mandan. He toured the southern plains, the upper Mississippi, and the great lakes regions. Catlin devoted himself to preserving the image of the Indian, whom he saw, as did all Europeans, as a single group – colorful, exotic, and fragile.

In this book, Catlin wrote that he “flew to their rescue – not of their lives or of their race (for they are doomed and must perish), but to the rescue of their looks and their modes, at which the acquisitive world may hurl their poison and every besom of destruction, and trample them down and crush them to death; yet phoenix-like, they may rise from the ‘stain on a painter’s pallet,’ and live again upon canvass, and stand forth for centuries yet to come, the living monuments of a noble race.” Catlin understood that the Plains Indian way of life depended on an abundance of buffalo – a dependence that would collapse after the white man descended on the landscape. “Oh insatiable avarice such! Wouldst thou tear the skin from the back of the last animal of this noble race, and rob thy fellow-man of his meant, and for it give him poison!” so Catlin wrote.

Catlin traveled as a guest of the American Fur Company. It was his goal to gain personal fame and fortune by preserving a pictorial record of the Native tribes within the borders of the United States. Under Catlin’s supervision, hundreds of engravings, reduced from the original paintings, were used in the publication of Letters and Notes. Catlin’s fusion of classicism and romanticism reflects the nineteenth-century European art movement. For the text, Catlin used a series of articles he had written for the New York Commercial Advertiser between 1832 and 1837.

An hour among the sands and wild wormwood – an hour among the oozing springs, and green grass around them – an hour along the banks of Saptin River – and we passed a line of timber springing at right angles into the plain; and before us rose the white battlements of Fort Hall!

TRAVELS IN THE GREAT WESTERN PRAIRIES

Thomas J. Farnham (1804-1848)

Poughkeepsie: Killey and Lossing, printers, 1841

First edition

F592 F225

Thomas Jefferson Farnham, a New Englander, practiced as an attorney in Peoria, Illinois. He heard a lecture on the Oregon country by Methodist missionary Jason Lee, who gone there in 1834. Inspired by the lecture, Farnham went overland in 1839 with a group of would-be settlers to Bent’s Fort and then north to the Oregon Trail. The “Peoria Party” left Independence on May 20, 1839, followed the Santa Fe trail to Fort Bent and then divided the company.

Five of the initial party abandoned the expedition in Santa Fe. One group, made up of eleven members, proceeded up the Platte River. Farnham, with four others, went up the Arkansas to South Park and then to the North Fork of the Platte. From there they proceeded to Brown’s Hole, and then up the Green River to Ham’s Fork. They arrived at Fort Hall, where they met with Joe Walker, who was in charge of the fort. They went on to Whitman’s Mission.

After a few week’s respite, Farnham continued on to Fort Walla, then to the Dalles, and down the Columbia to Fort Vancouver. The trip ended on September 23rd. This was the first overland migration to Oregon.

One of Farnham’s over-glorious goals for his adventure was to kick out the British from Oregon country. Ironically, several of the men in his expedition were English. Farnham’s book was a strong advocate for American control of Oregon. Farnham began this argument with his opening statement: “Some of our number sought health in the wilderness – others sought wilderness for its own sake – and others sought a residence among the ancient forests and lofty heights of the valley of the Columbia.” He continued by celebrating the West, capable of offering health and “wilderness for its own sake,” with vivid descriptions of the geography and insights into native culture.

In later writings, Farnham’s propagandistic enthusiasm for the West notably included the rampant racism of the time. Only the “Anglo-Saxon race” could do the possibilities the land presented justice. He offered very clear, in his mind, expressions to the superiority of “Americans” over the Spanish/Mexican/Indian peoples he had no problem dispossessing.

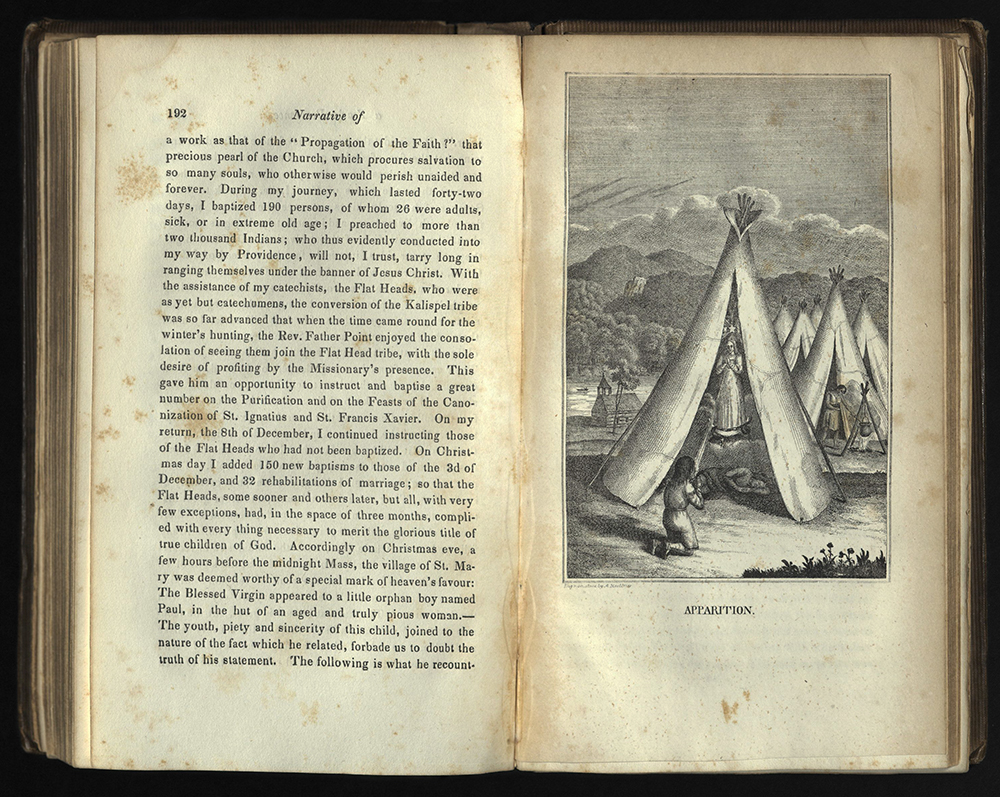

Accordingly on Christmas eve, a few hours before the midnight Mass, the village of St. Mary was deemed worthy of a special mark of heaven’s favour: The Blessed Virgin appeared to a little orphan boy named Paul, in the hut of an aged and truly pious woman.

LETTERS AND SKETCHES

Pierre-Jean De Smet (1801-1873)

Philadelphia: M. Fithian, 1843

First edition

F592 S63

Pierre-Jean De Smet was a Belgian Jesuit. He spent his adult life traversing the Great Plains, founding missions and working to convert the Potawatomi, Dakota, and other native peoples. In 1821, he sailed to the Baltimore to begin his missionary work. Eighteen months later, he was transferred to Missouri, where he was ordained in 1827. He taught at St Regis Seminary, a school for Native American boys, from whom he learned a little about their customs.

In 1833, De Smet returned to Belgium for medical reasons, where he recruited men, supplies, and money for a Missouri mission. When he returned to the United States he worked as a missionary to the Potawatomi Indians at Council Bluffs, Iowa, visiting the Yankton and Santee Sioux in an attempt to negotiate peace between the two tribes. He traveled to the Rocky Mountains in the 1840s, from St. Louis to Fort Vancouver and back.

This book contains sixteen letters he wrote to his supervising priest during his travels. His main goals on this trip and a subsequent one was to establish missions for Native Americans, in particular the Blackfoot. In one letter, De Smet wrote of white settlers, “Nothing frightens them. They will undertake anything. Sometimes they halt – stumble once in awhile – but they get up again and march onward.”

I am almost ashamed to confess that scarcely a day passes without my experiencing a pang of regret that I am not now roving at large upon those western plains. Nor do I find my taste peculiar; for I have hardly known a man, who has ever become familiar with the kind of life which I have led for so many years, that has not relinquished it with regret. ...the wild, unsettled and independent life of the Prairie trader, makes perfect freedom from nearly every kind of social dependence an absolute necessity of his being. He is in daily, nay, hourly exposure of his life and property, and in the habit of relying upon his own arm and his own gun both for protection and support. Is he wronged? No court or jury is called to adjudicate upon his disputes or his abuses, save his own conscience; and no powers are invoked to redress them, save those with which the God of Nature has endowed him. He knows no government — no laws, save those of his own creation and adoption…The exchange of this untrammeled condition — this sovereign independence, for a life in civilization, where both his physical and moral freedom are invaded at every turn, by the complicated machinery of social institutions, is certainly likely to commend itself to but few,— not even to all those who have been educated to find their enjoyments in the arts and elegancies peculiar to civilized society; — as is evinced by the frequent instances of men of letters, of refinement and of wealth, voluntarily abandoning society for a life upon the Prairies, or in the still more savage mountain wilds.

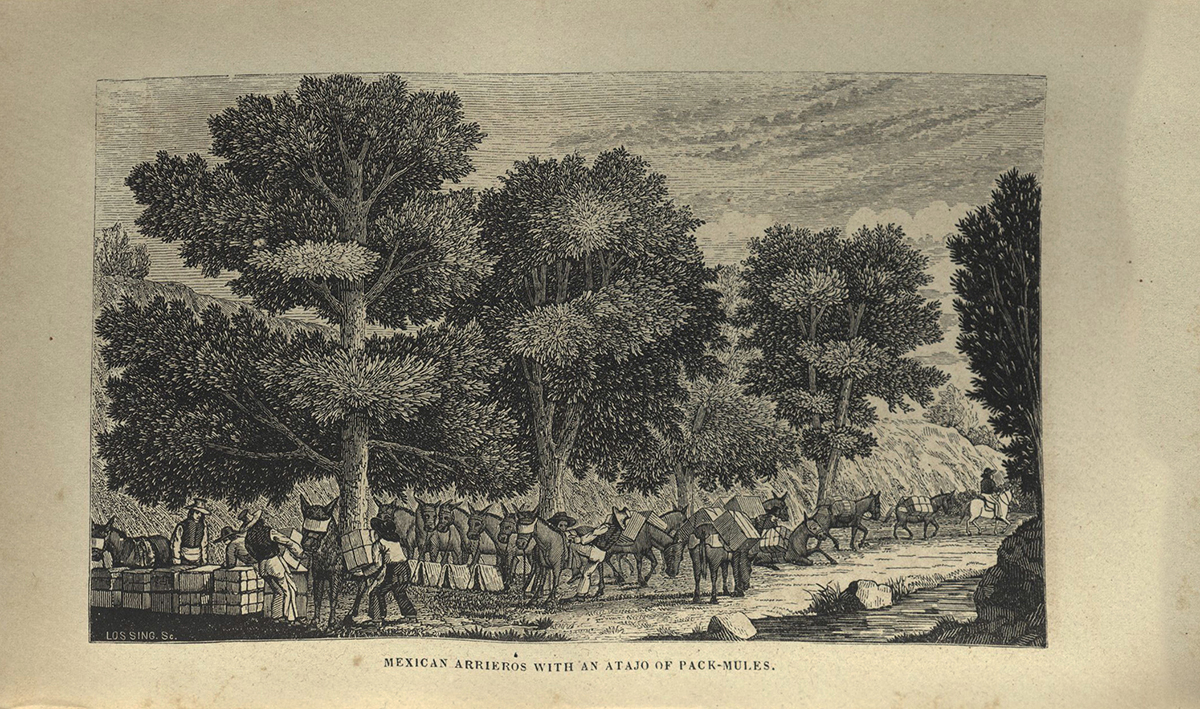

COMMERCE OF THE PRAIRIES

Josiah Gregg

New York: H. G. Langley, 1844

First edition

F800 G8

Josiah Gregg, born in Tennessee and raised in Missouri, studied mathematics and surveying. He was convinced that a trip west would restore his failing health. In 1831, he set out with a trading caravan for Santa Fe on the first of what would be eight journeys across the prairies.

In 1831, the American trade with New Mexico was a decade old. Business procedures had already been developed, but travel along the Santa Fe Trail was still exotic.

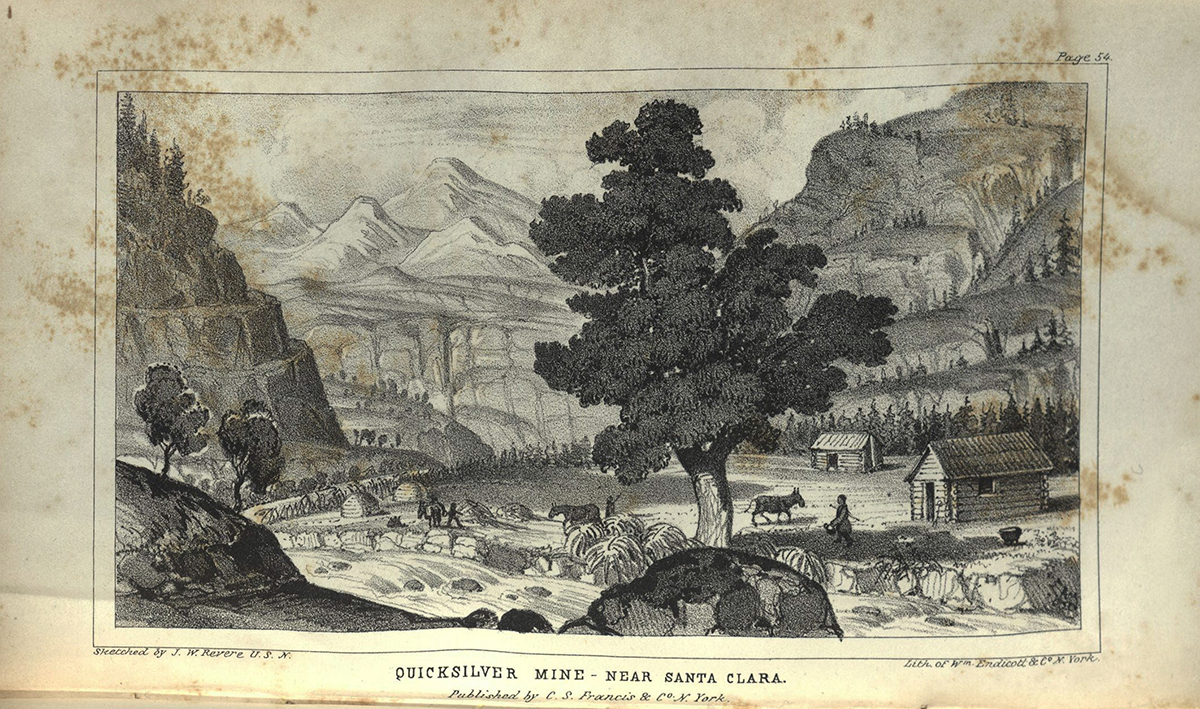

On his first trip, Gregg learned Spanish and bookkeeping. The trip was exciting, but also serious business. Gregg had a keen interest in science and took careful notes of the geography and geology of the Southwest, detailing the culture of its inhabitants, in particular the Native Americans in Texas and New Mexico. He outlined a trail from Van Buren, Arkansas to Chihuahua. This route, following the Canadian River, later became a main route for prospectors headed to California.

A decade after his last trip, he began compiling his travel notes into a readable manuscript and traveled to New York to find a publisher. His was the first book published about the Santa Fe Trail. Gregg captured the romance of the early wagon train enterprises – the approach into Santa Fe, wagon masters dressed in their Sunday best, headed toward the customhouse, while locals shouted their arrival.

Gregg’s work, published in two volumes, was an immediate success, going through two more editions in 1845, a fourth and fifth edition, and a sixth edition in 1857 under a different title. It was translated into French and German. Sales were brisk in England.

Gregg’s account of his travels was scrupulously accurate. It contains vivid descriptions of desert mirages and buffalo hunts. A large folded map is the first to display the Staked Plains of Texas, and includes the locations of forts, military roads, and trading posts. It identifies the Oregon Trail and Native American settlements, and traces the routes of Gregg’s exploring predecessors, including Stephen Long, and Zebulon Pike.

After his travelling adventures, Gregg studied medicine, a field he had dropped a decade earlier, and became a physician. He wanted to return to Santa Fe, but those plans were thwarted by the Mexican War. He became a newspaper correspondent and served as a guide and interpreter for Brig. Gen. John Wool and then for Col. Alexander Doniphan. He established a medical practice in Mexico where he also studied botany. From Mexico he traveled to San Francisco, visiting the gold fields. He led a small expedition over the coastal mountains of California and discovered what is now called Humboldt Bay. He died from injuries he received falling from a horse.

The wagons marched slowly in four parallel columns, but in broken lines, often at intervals of many rods between. The unceasing ‘crack, crack,’ of the wagoner’s whips, resembling the frequent reports of distant guns, almost made one believe that a skirmish was actually taking place between two hostile parties: and a hostile engagement it virtually was to the poor brutes, at least; for the merciless application of the whip would sometimes make the blood spirt from their sides – and that often without any apparent motive of the wanton carrettieri, other than to amuse themselves with the flourishing and loud popping of their lashes!

In this operation they frequently demonstrate a wonderful degree of skill in the application of their strength. A single man will often seize a package which, on a ‘dead lift,’ he could hardly have raised from the ground, and making a fulcrum of his knees and a lever of his arms and body, throw it upon the mule’s back with as much apparent ease as if the effort cost but little exertion. At stopping-places the task of unpacking is executed with still greater expedition.

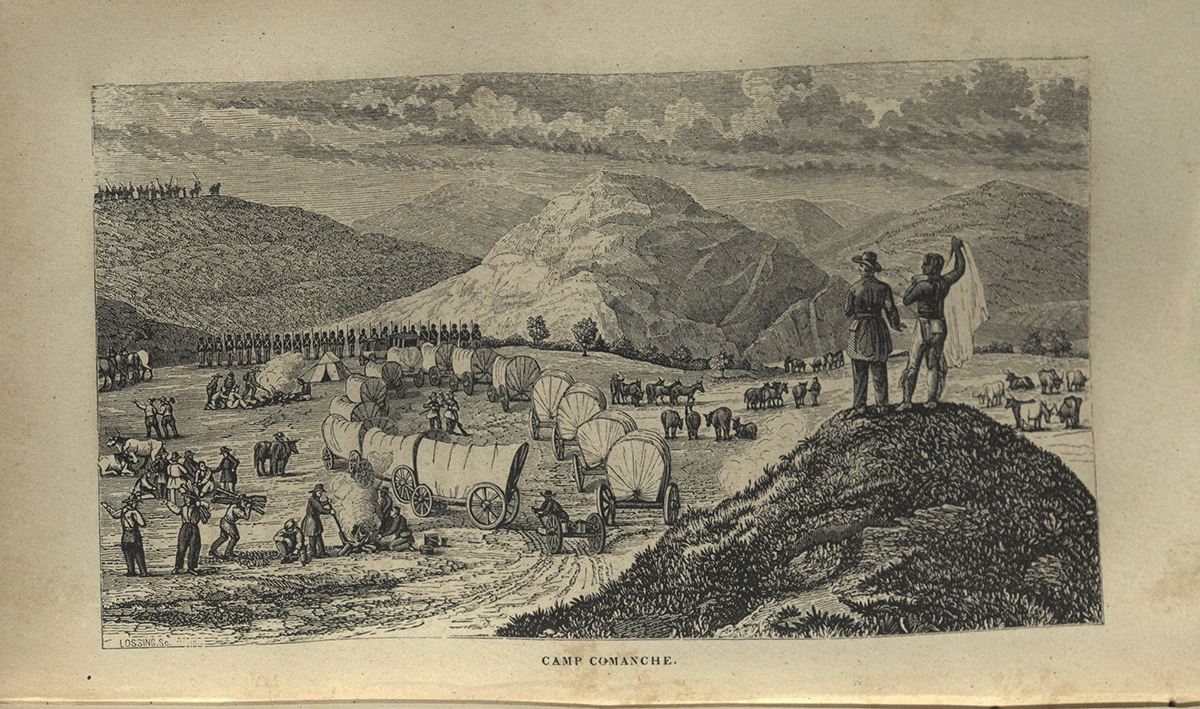

The party consisted of about sixty warriors, at the head of whom rode an Indian of small stature and agreeable countenance, verging on the age of fifty. He wore the usual Comanche dress, but instead of moccasins, he had on a pair of long white cotton hose, while upon his bare head waved a tall red plume, -- a mark of distinction…

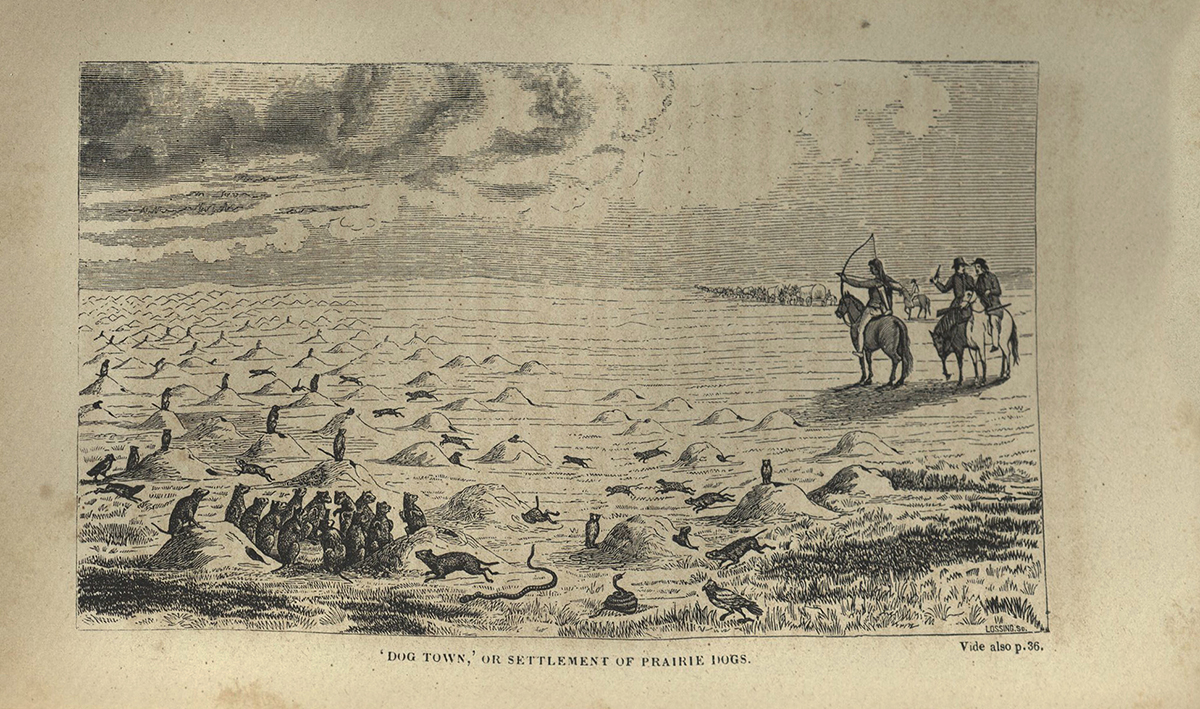

Approaching a ‘village,’ the little dogs may be observed frisking about the ‘streets’ – passing from dwelling to dwelling apparently on visits – sometimes a few clustered together as though in council – here feeding upon the tender herbage – there cleansing their ‘houses,’ or brushing the little hillock about the door – yet all quiet.

El estado que hoy guarda la república, las tendencias y conatos de una nación vecina para continuar usurpando nuestro territorio, el carácter de invasión que manifiesta toda la prensa americana y nuestra inercia, me hacen temblar por la suerte de la república, si no se atienden nuestras fronteras, principalmente mi Departamento.

COLECCION DE DOCUMENTOS ...

Mexico: Imprenta de la Voz de Pueblo, 1845

First edition

F864 C37 1845

Manuel Castañares was a former representative from California in the Mexican National Congress. His work here focuses on California’s indigenous population, missions, agriculture, ports, Russian establishments, civic structure, and a gold discovery in 1843.

Castañares pleads for the Mexican federal government to proactively protect California because, should it fail to do so it, “will be irredeemably lost, and I tremble at the sad consequences…A powerful foreign nation will pitch its camps there…Then will sprout the seeds of today lying ignored in the soil; then her mines will be worked, her ports crowded, her fields cultivated…” At the time, the United States had no claim to California, other than desire.

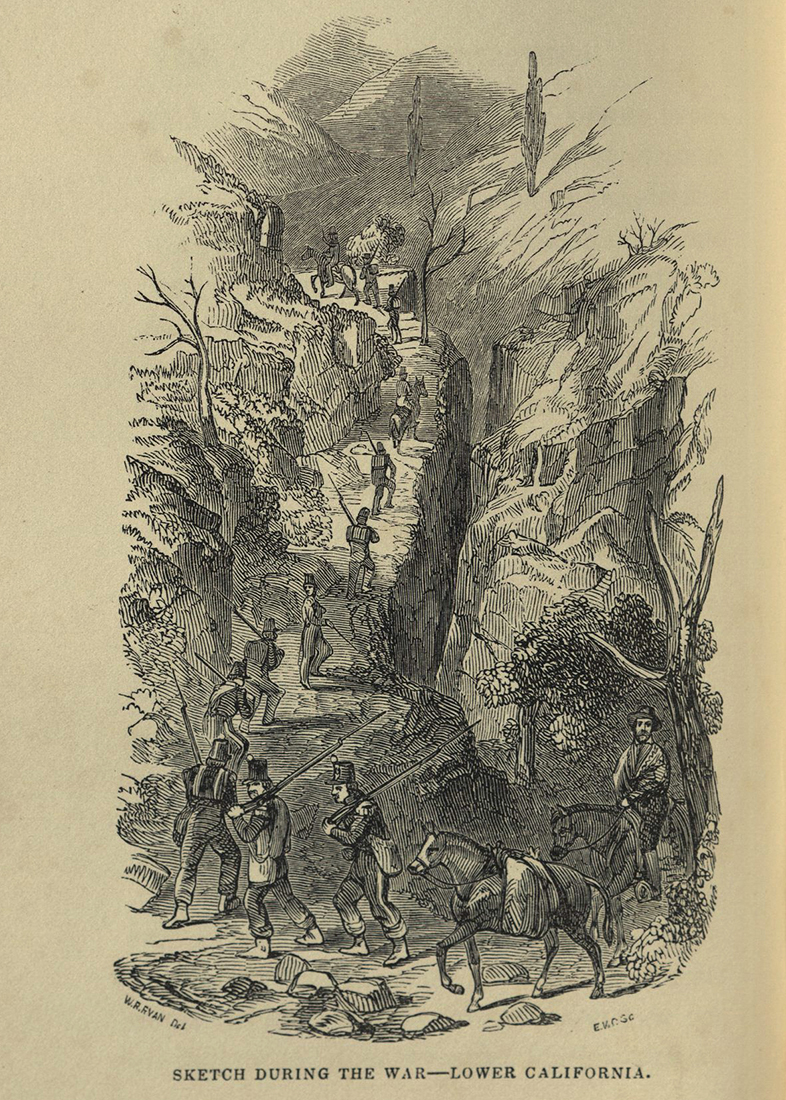

A year following the publication of Castañares’s concerns about unrest in California and the assertive nature of an American government perched on the California frontier, Anglo-Californians learned of the outbreak of war with Mexico, and raised a standard for a “Bear Flag Republic,” hoping for an independent, American, California. At the time, about five hundred Americans were more or less permanently settled in California, amongst approximately twelve thousand Mexicans. Only a few of the Americans had obtained grants of land from Mexican authorities.

In the spring of 1846, John C Fremont arrived at Sutter’s Fort with a small group of soldiers, ostensibly to make a scientific survey for the United States government. Fremont encouraged the American settlers to form militias in preparation for a rebellion against Mexico. More than thirty Americans, made up of settlers, hunters, and adventurers, led by William Ide, invaded a Mexican outpost just north of San Francisco. Although Fremont and his soldiers did not participate, he did not prevent the attack.

Ide had been an Elder in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and president of a branch of the church in Illinois. He served on the delegation at the Mormon convention to promote Joseph Smith, Jr.’s candidacy for President of the United States in 1844. After Smith was murdered later that year, Ide headed west, arriving at Sutter’s Fort in 1845.

On July 5th, having successfully bullied a sympathetic Mexican general into surrender, the rebels proclaimed Fremont their governor. By early 1847, California officially came into the possession of the United States.

Eleven copies of this pamphlet are known to exist, nine of which are the in the United States. Rare Books copy in contemporary plain paper wrappers.

Taking leave at this point of the water of the Bear River, and of the geographical basin which encloses the system of rivers and creeks which belong to the Great Salt Lake, and which so richly deserves a future and detailed and ample exploration, I can say of it, in general terms, that the bottoms of this river, (Bear) and some of the creeks which I saw, form a natural resting and recruiting station for travelers, now, and in all time to come. The bottoms are extensive; water excellent; timber sufficient; the soil good, and well adapted to the grains and grasses to such an elevated region.

REPORT OF THE EXPLORING EXPEDITION TO THE ROCKY ...

John Charles Fremont (1812-1890)

Washington: Gales and Seaton, printers, 1845

First edition, Senate issue

F592 F874 1845

John Charles Fremont played a major role in opening up the American West to settlement by white pioneers. Fremont was the son of a Québécois father and a Virginian mother. His parents entertained influential people at their home in Charleston, South Carolina.

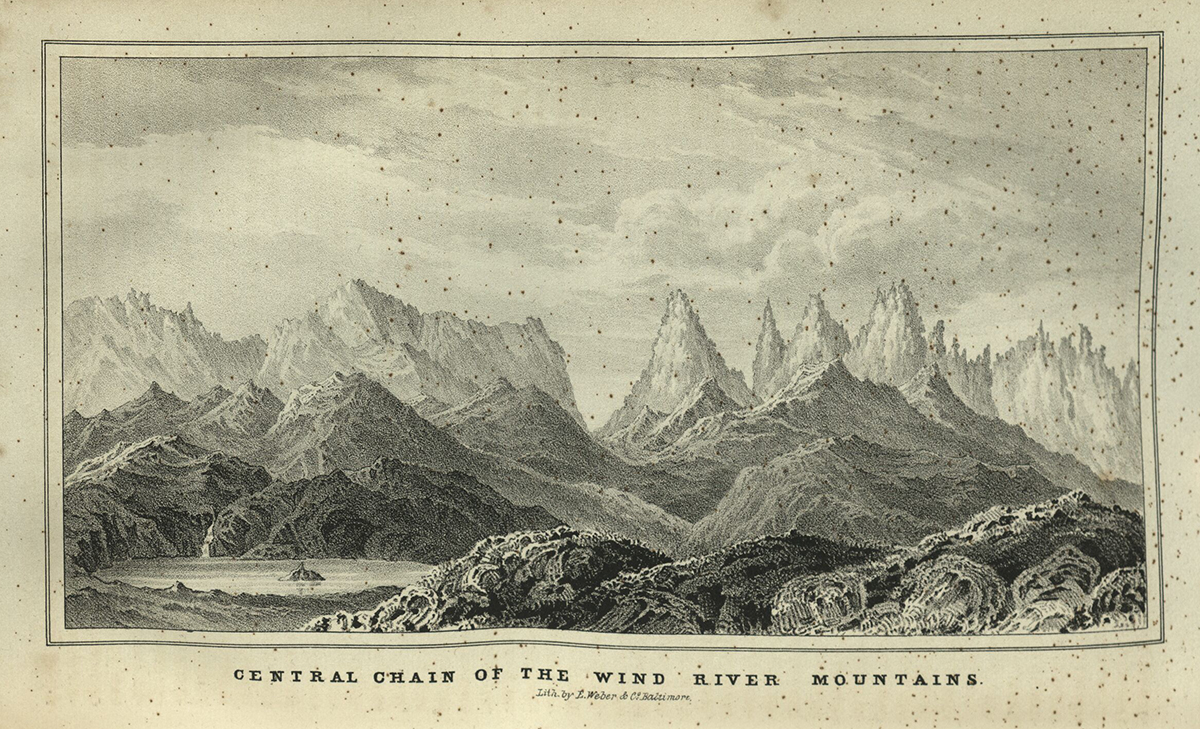

Fremont was appointed second lieutenant in the U.S. Topographical Corps, quickly rising within its ranks. Through the influence of his father-in-law, Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, who was the chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, Fremont was charged with leading an expedition to the Rocky Mountains in 1832. His party of twenty-five men, including Kit Carson, left the Kansas River, following the Platte River to the South Pass. From Green River the party explored the Wind River mountain range, where Fremont climbed a 13,745-foot peak, planted an American flag and claimed the Rocky Mountains and the West for the United States.

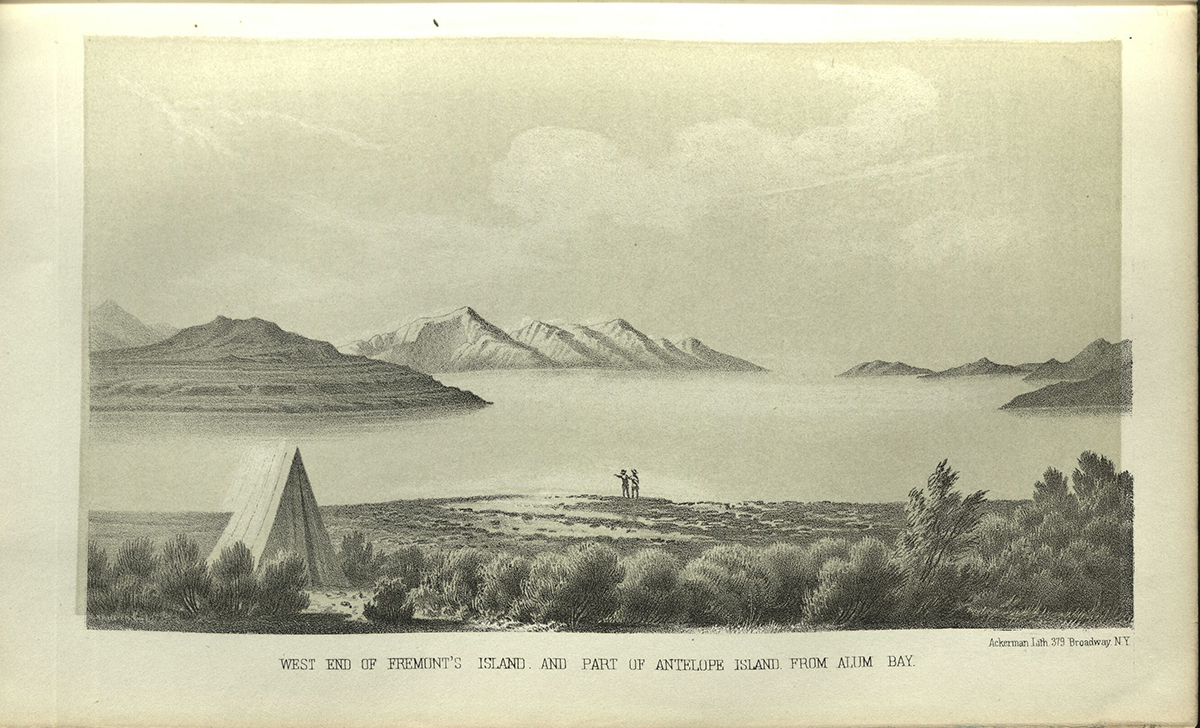

This report documents the first two of his four expeditions. The first, in 1842, explored the country between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, following the Kansas and Great Platte Rivers. The second, in 1843-44, explored Oregon and Northern California, traveling from the Great Salt Lake to Vancouver, then south to San Francisco, and finally east over the California desert.

This second expedition linked the interior with the surveys of Charles Wilkes along the Pacific Coast. Fremont mapped and confirmed the Oregon Trail as the best route for pioneers heading West.

In all, Fremont’s expeditions explored 20,000 miles of wilderness, although Fremont wrote of “about ten thousand miles of actual traveling and traversing in the wilderness which lies between the frontiers of Missouri and the shores of the Pacific.” The first edition of his report, published for the American Senate, included a large map produced by Charles Preuss.

Preuss’s accurate map was of primary importance to those hoping to undertake the difficult journey west. Based on direct observation, it was more trustworthy than anything else available at the time. Fremont supplemented the map with a table of distances from Kansas Landing to Fort Vancouver.

Fremont’s report mapped out all California rivers south of the American River and the three Colorado rivers. The maps became essential for gold rush travelers.

The year after Fremont’s report was published, 1846, saw an explosion of national expansion: war over Texas with Mexico, the settlement of the dispute over ownership of the Pacific Northwest, a vast overland emigration to Oregon and California, and the Mormon flight to Utah Territory.

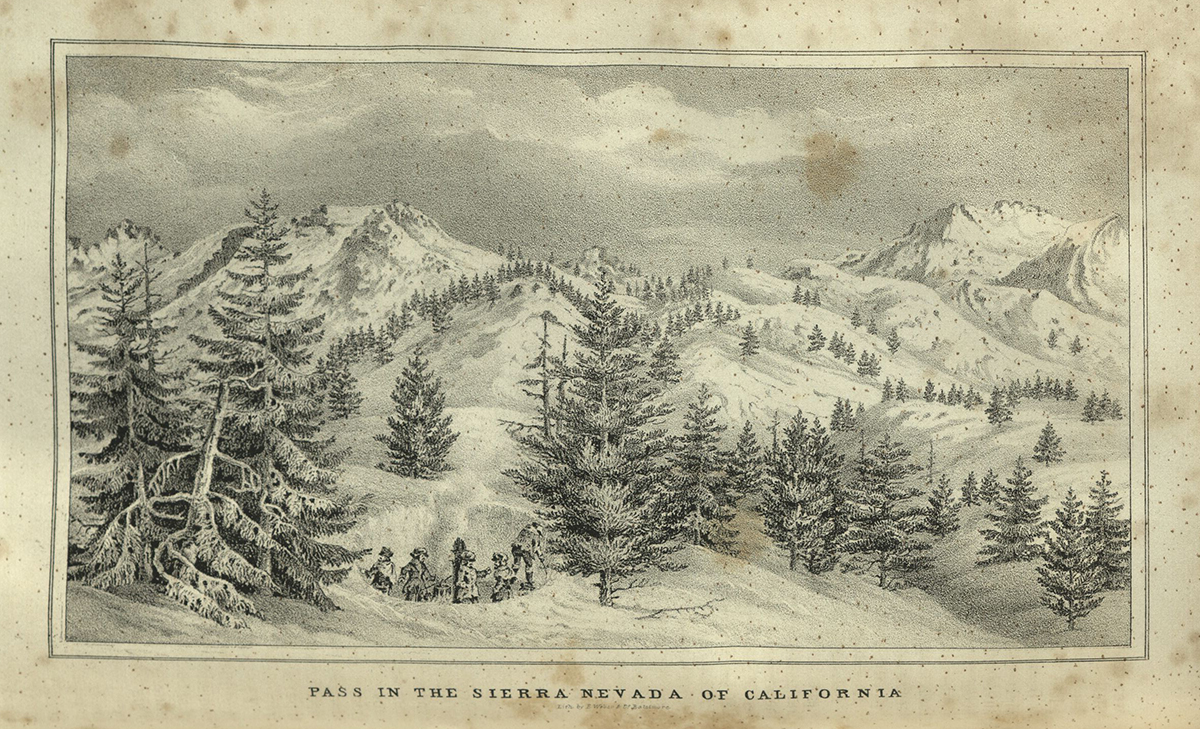

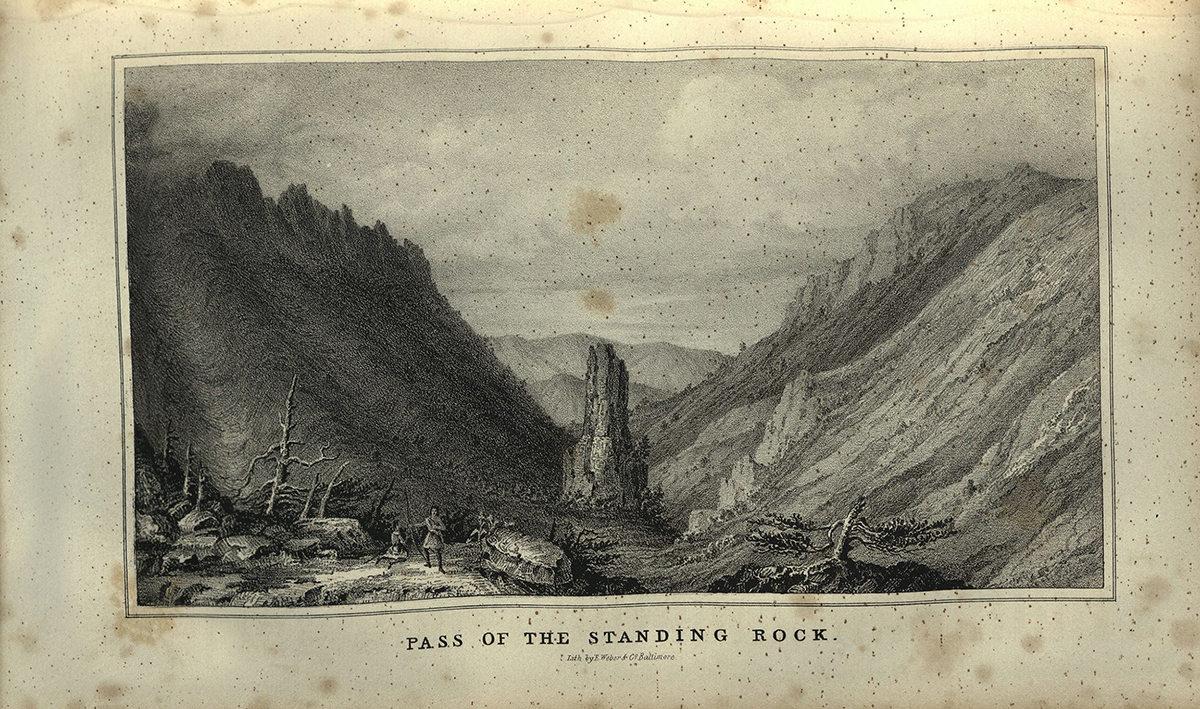

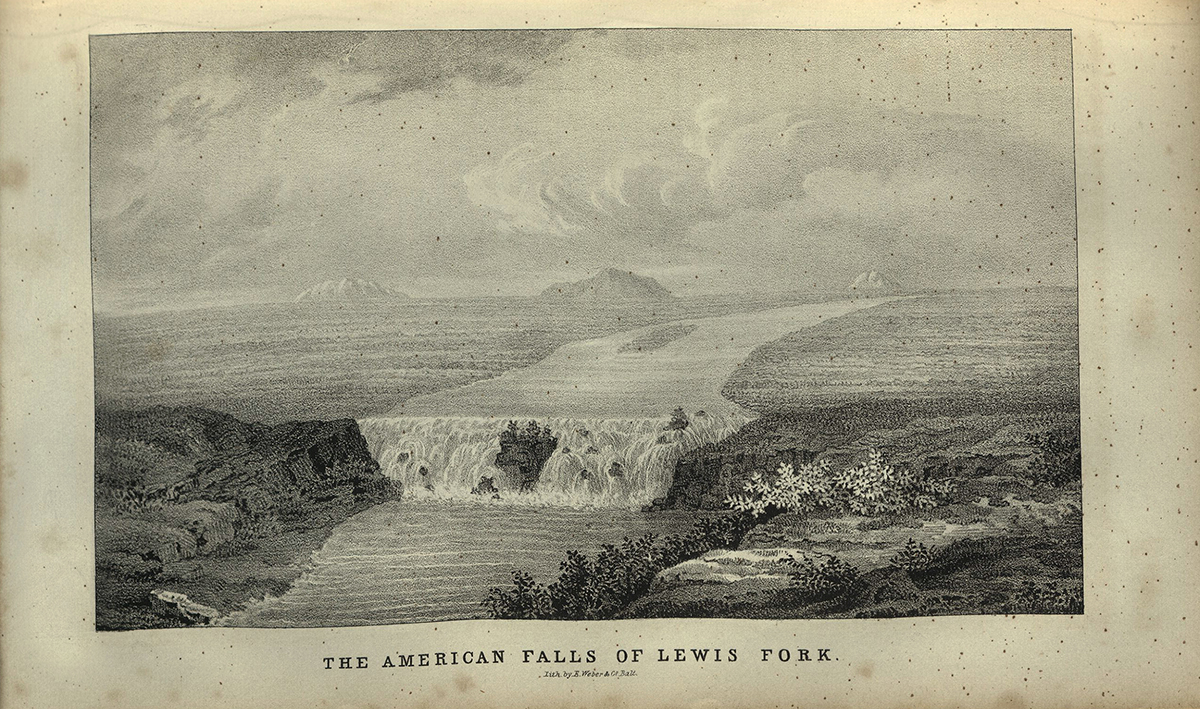

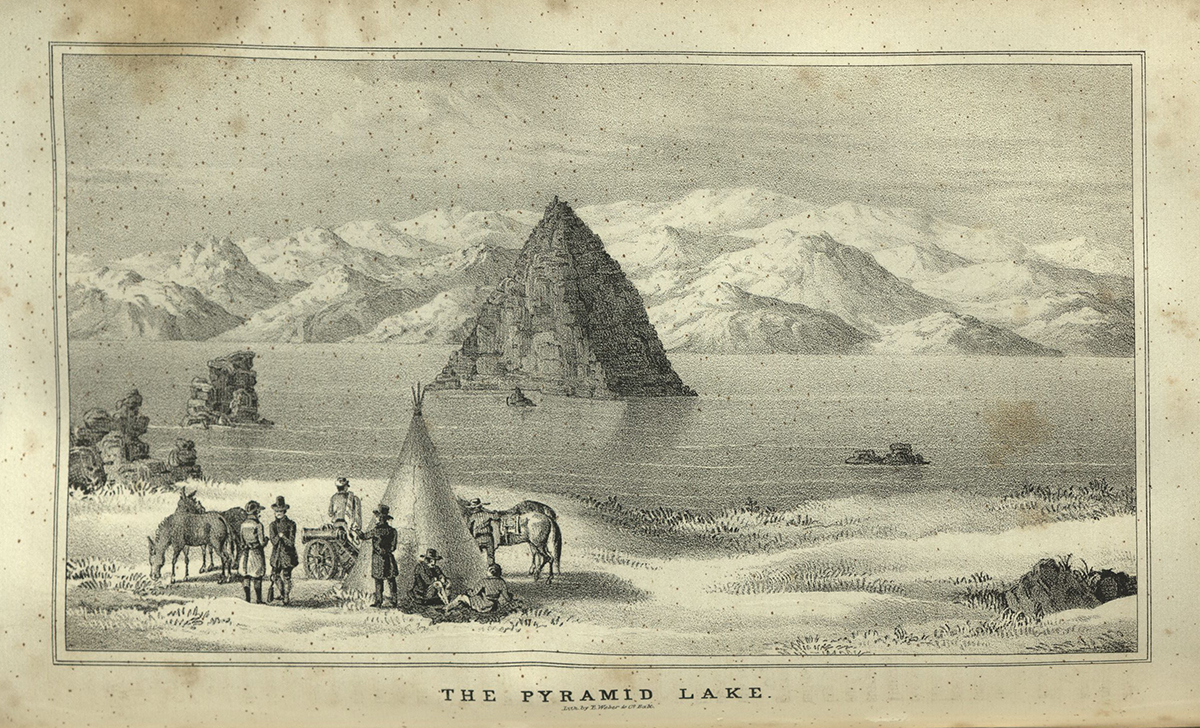

Fremont’s report included twenty-two lithographic plates. The plates evoked a rugged but dramatic landscape. In one plate, “Pass in the Sierra Nevada of California,” the explorers are depicted deep in snow.

Putting on our snow shoes, we spent the afternoon in exploring a road ahead. The glare of the snow, combined with great fatigue, had rendered many of the people nearly blind…

The report, written with the help of his wife, Jessie Benton Fremont, became the cornerstone of early western exploration, capturing public imagination. Mrs. Fremont’s writing added a romantic quality to the undertaking. It introduced a public readership to then little-known mountain man Christopher “Kit” Carson, who entered into a national mythology about the West.

In one instance, Fremont described the Great Salt Lake valley as “bucolic.” Only a few years later, Brigham Young read Fremont’s report which helped him decide that the remote location was suitable for his persecuted Mormon followers. Fremont’s report had international interest, as well. The publisher of Charles Darwin’s books in the United States, William H. Appleton, sent Darwin a copy of this report.

The U.S. Senate ordered the publication of ten thousand copies of Fremont’s reports. Twenty-five editions were printed between 1845 and 1860, although the maps were not included in several of the later versions. D. Appleton & Company published several of these editions.

It looks, at this distance of about thirty miles, like what it is called – the long chimney of a steam factory establishment, or a shot tower in Baltimore.

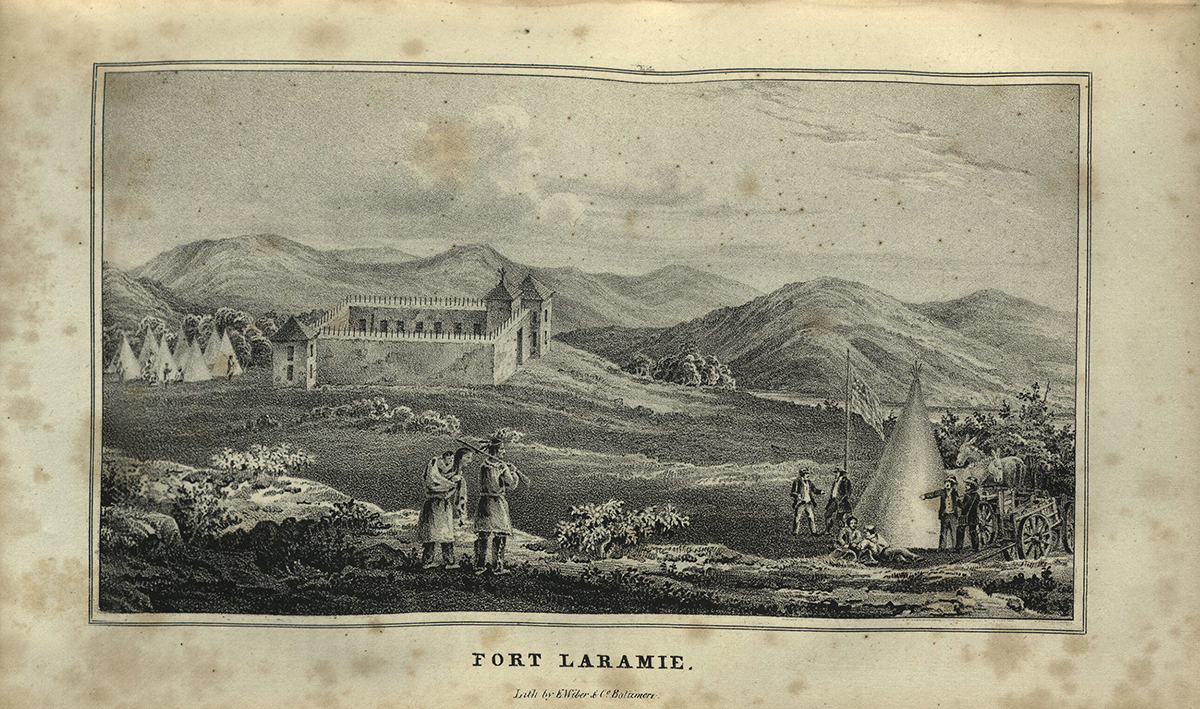

The fort had a very cool and clean appearance. The great entrance, in which I found the gentleman assembled, and which was floored, and about fifteen feet long, made a pleasant, shaded seat, through which the breeze swept constantly; for this country is famous for high winds.

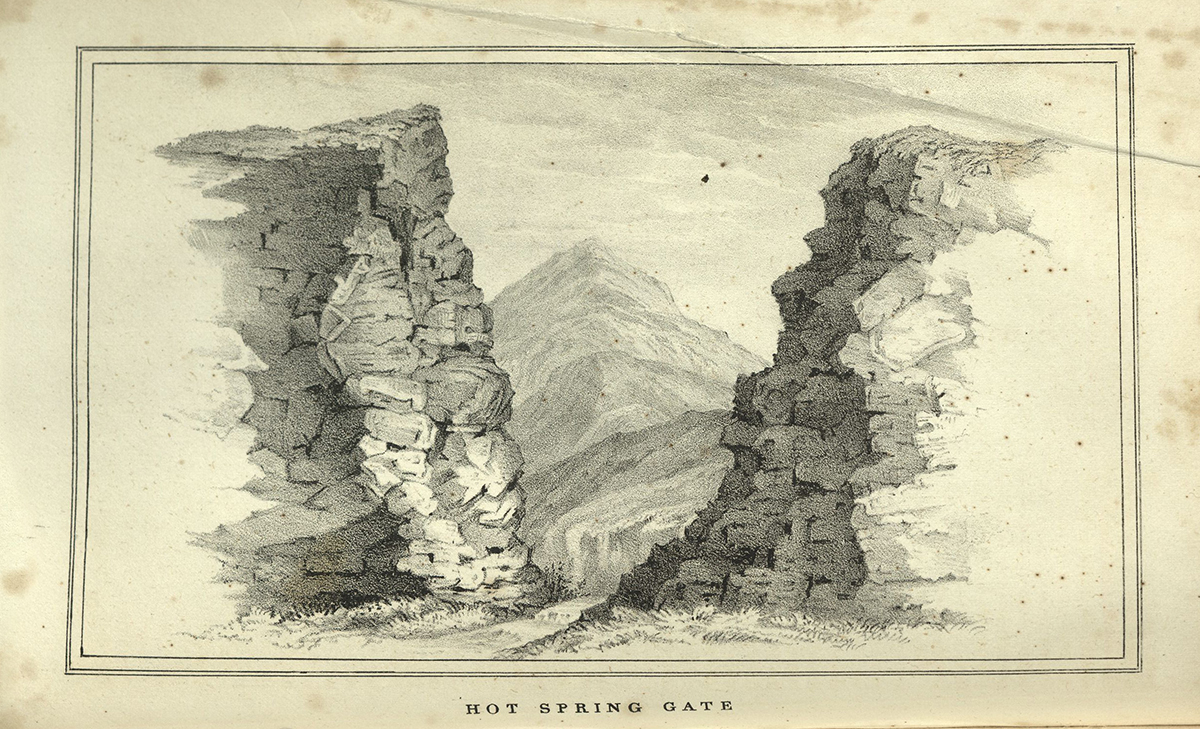

Crossing the ridge of red sandstone, and traversing the little prairie which lies to the southward of it, we made in the afternoon an excursion to a place which we have called the Hot Spring Gate.

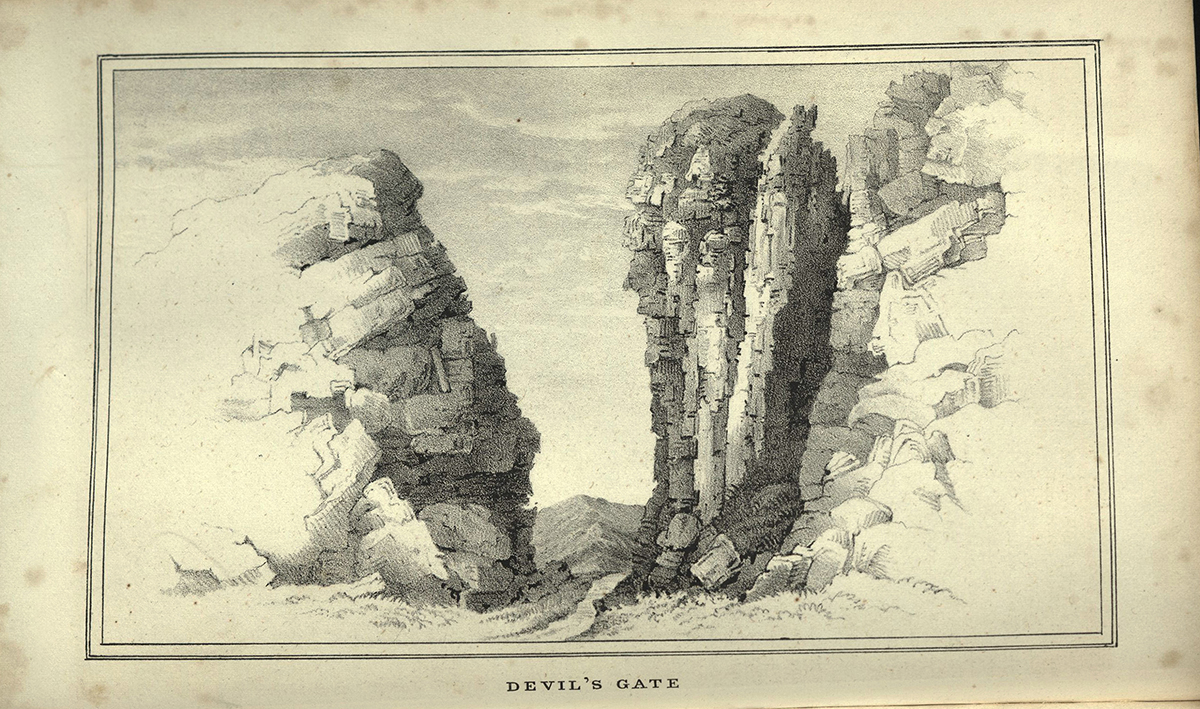

Five miles above Rock Independence we came to a place called the Devil’s Gate, where the Sweet Water cuts through the point of a granite ridge.

Their wildness seems well suited to the character of the people who inhabit the country.

Around us, the whole scene had one main striking feature, which was that of terrible convulsion.

… a huge rock, fallen from the cliffs above, and standing perpendicularly near the middle of the valley, presents itself like a watch tower in the pass…generally the mountains rise abruptly up from comparatively unbroken plains and level valleys…where a green valley, full of foliage, and a hundred yards wide, contrasts with naked crags that spire up into a blue line of pinnacles…sometimes crested with cedar and pine, and sometimes ragged and bare.

In the south is a bordering range of mountains, which, although not very high, are broken and covered with snow; and at a great distance to the north is seen the high, snowy line of the Salmon river mountains, in front of which stand out prominently in the plain the three isolated rugged-looking little mountains…

…we encamped on the shore, opposite a very remarkable rock in the lake, which had attracted our attention for many miles.

The most direct route, for the California emigrants, would be to leave the Oregon route, about two hundred miles east from Fort Hall, thence bearing west southwest to the Salt Lake ; and thence continuing down to the bay of San Francisco, by the route just described.

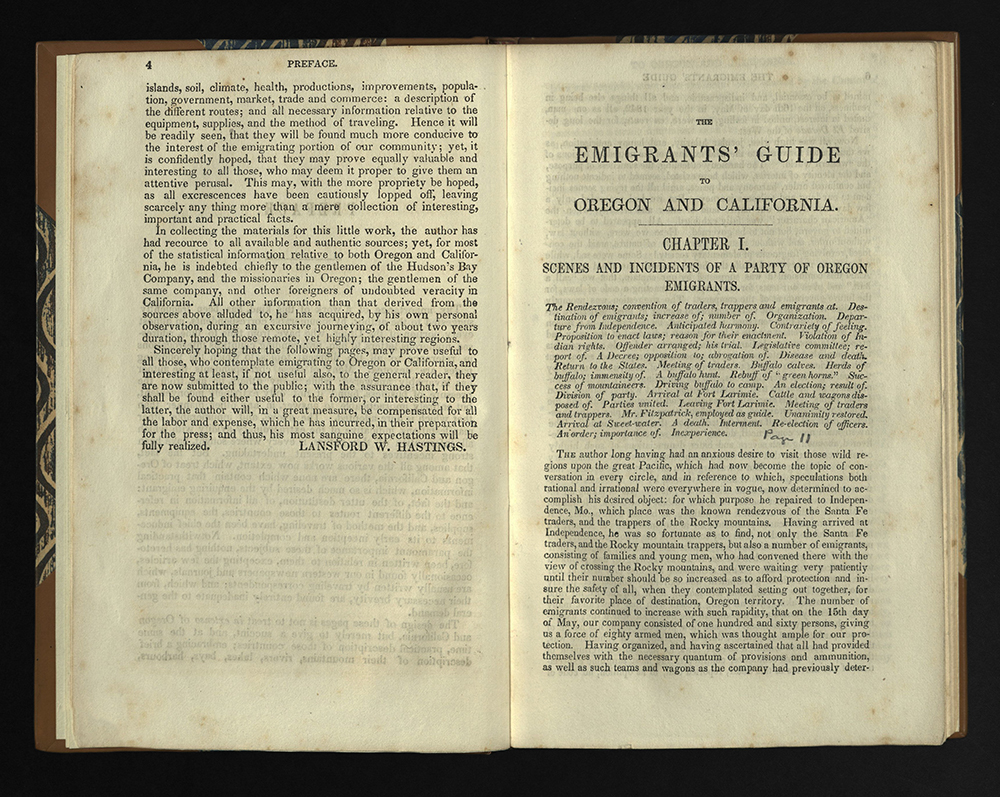

THE EMIGRANT'S GUIDE TO OREGON AND CALIFORNIA

Lansford Warren Hastings (1819-1870?)

Cincinatti: G. Conclin, 1845

First edition

F864 H345

Lansford Warren Hastings was a real-estate investor from Ohio. In 1842, at the age of twenty-three, he made a trip west to California, where he developed financial and political interests. His Emigrant’s Guide became a bestseller.

The book had almost no practical advice, in spite of the crowing in its preface of providing "a description of the different routes; and all necessary information relative to the equipment, supplies, and the method of traveling" with the caveat that "all excrescences have been cautiously lopped off, leaving scarcely any thing more than a mere collection of interesting, important and practical facts." To make up for the lack of "excrescences," Hastings regaled the reader with lengthy and snarky anecdotes regarding "Californians," gamblers and drunks, all. "How different are the priests of California from those of the same denomination of christians in our own country?"

In his guide he depicted Indians as lazy and Mexicans as dishonest, blaming much of the latter on the priests of the Roman Catholic Church. "At times, I sympathize with these unfortunate beings, but again, I frequently think, that perhaps, are thus ridden and restrained and if they are thus priest ridden, it is, no doubt, preferable, that they should retain their present riders." As for Indians, Hastings wrote, with no irony, that they "in numerous instances, abandoned their old haunts, and re-established in other portions of the country, but for what cause, it is difficult to ascertain, with any degree of certainty, for the sites which have been thus abandoned, appear in many instances, to possess advantages much superior, to those which have been subsequently selected." Hastings’ "little work," as he called it, was inspirational to those wishing to escape the crowded conditions and poor economy of the east and Midwest.

Hastings’ book promoted the land and climate of California as ideal companions for hardworking Americans. Many sold farms and gave up businesses as the lure a better life captivated their imaginations.

Hasting’s guide book had good information: "All persons designing to travel by this route, should, invariably, equip themselves with a good gun" and "It would, perhaps, be advisable for emigrants, not to encumber themselves with any other, than those just enuerated; and it is impracticable for them, to take all the luxuries, to which they have been accustomed, and as it is found, by experience, that, when upon this kind of expedition, they are not desired, even by the most devoted epicurean."

His guidebook also had bad information. Eager to sell land, he encouraged travelers to forget about Oregon and make their way to California, suggesting a cutoff through the Wasatch Mountains, passing to the south of the Great Salt Lake and then across the salt flats to rejoin the California Trail at the Humboldt River. A conversation with John C. Fremont suggested to Hastings that this was a viable possibility.

Hastings, who had not, in fact, traveled this route himself, was sure the shortcut would save travelers valuable time and began his promotion. The cutoff avoided anywhere from two hundred to four hundred and fifty miles off the northwestward route to Fort Hall and thence to the Humboldt River, saving weary travelers around fifteen to thirty days. But this was a new wagon road and fraught with difficulties.

It was Hastings’ intent to attempt the crossing and he headed east to pick up a group of pioneers. Hasting’s followed Fremont’s tracks eastward to the Salt Lake Valley. He went up Parley’s Canyon, over Big Mountain, and on to the Weber River, traveling upstream to Echo Creek, crossing Bear River near present-day Evanston, Wyoming. From there he intersected with the Oregon Trail. He thought that the Great Salt Lake Desert might pose a problem for groups heading west, but having crossed it on horseback, failed to recognize how difficult crossing the desert mud would be for heavily-laden wagons. His traveling guide, James Clyman, had twenty years experience in the area and urged California-bound emigrants not to take this cutoff. The route turned out to be fatal for members of one eager group, the Donner Party.

I cannot refrain from repeating, in this place, what I have for many years been convinced of – that the good of the Indians would be much advanced, and the peace of the country much more effectually secured, if Congress would pass a law declaring the whole of the Indian country under martial law.

REPORT OF A SUMMARY CAMPAIGN TO THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS ...

Stephen Watts Kearny (1794-1848)

Washington: Ritchie & Heiss, 1845

First edition

E405.2 K4 1845

In 1845, five companies of dragoons consisting of sixteen officers and more than two hundred and fifty enlisted men, under the command of Colonel Stephen Kearny, left Fort Leavenworth, heading northwest on what would become the Oregon Trail, to Wyoming, down along the Rocky Mountains to Mexican territory, and north again via the Santa Fe Trail. The march displayed the military power of the United States to native tribes and to the British government. Kearny took every opportunity on the march to display the might of the United States government. He flashed two mountain howitzers and lots of carbines. In all, Kearny covered a total distance of 2,073 miles in 99 days.

In his report to the United Stated Congress, Kearny described the route, his encounters with the Pawnee, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho; the soil and landscape, and the traders moving goods to and from Santa Fe.

Near Fort Laramie, where he left one hundred dragoons, Kearny met with the Sioux to try to persuade them not to attack the emigrant wagon trains heading West. He also admonished them against imbibing in the alcohol offered them by traders. According to Kearny, white traders from New Mexico had followed the Taos Trail to Colorado and beyond for decades to exchange whiskey for furs and buffalo robes.

Kearny wrote that the best way to protect American settlers traveling to Oregon was to continue marches such as these to remind native tribes of the “facility and rapidity with which our dragoons can march through any part of their country.” He advocated seasonal patrols over the emigrant route to Oregon, arguing against the expense of permanent posts.

Having passed these rapids, we arrived, in a few minutes, at Oregon City, situated at the Falls of the Willammette, the place of our destination. This was the 13th of November, 1843, and it was five months and nineteen days after we left Independence, in Missouri. Here we were able to procure such things as were really necessary to make us comfortable; and, what was most especially pleasing to us, an abundance of substantial food.

ROUTE ACROSS THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS

Overton Johnson and William H. Winter (1819-1879)

Lafayette, IN: J.B. Semans, printer, 1846

First edition

F851 J68

This is one of the earliest overland guide books to the Oregon Trail, second only to William Hasting’s guide published a year earlier.

Overton Johnson and William Winter, both from Indiana, left Independence, Missouri on May 25, 1843 and arrived in the Willamette Valley on November 13 of that year. Like others, they made the trip both for adventure and economic opportunity. Winter went on to California the following year, and then met up with Johnson by accident at Fort Hall, Idaho. The two returned to Indiana together, where they arranged the publication of this book in time for the 1846 emigrant season.

The book gives an account of their contact with Indians, their customs, dances, and methods of warfare. The route traveled to California and the return to Ft. Hall is vividly described. The guidebook mentions the Bear Flag Rebellion, the production of wine, and the presence of gold in northern California.

Twelve of their fellow travelers didn’t make it, including a six-year-old who was crushed by a wagon wheel. Winter eventually settled in Napa Valley.

The Appendix includes complete instructions to emigrants with regard to supplies, equipment, an itinerary, and notes on various stopping places along the way.

They passed their time in play, and roaming about from house to house, dancing and sleeping and this was their only occupation…The women were obliged to gather seeds in the fields, prepare them for cooking, and to perform all the meanest offices as well as the most laborious. It was painful in the extreme, to behold them with the infants, hanging upon their shoulders, groping about in search of herbs and seeds.

LIFE IN CALIFORNIA ...

Alfred Robinson (1806-1895)

New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1846

First edition

F864 R65 1846

Originally from Massachusetts, Alfred Robinson arrived in California in 1829 as representative for the hide-trading and shipping firm Bryant, Sturgis & Co. He married Anita de la Guerra de Noriega y Carrillo, heiress of the prominent De Guerra family of Santa Barbara.

Life in California is the first book on California published in English written by a resident, containing Robinson’s personal observations of Spanish rule and detailed descriptions of Alta California under Mexican rule. It is a comparatively sympathetic portrait of the Californios living under the Mexican Republic.

The book includes Robinson’s translation of Fr. Geronimo Boscana’s (1776-1831) Chinigchinich, an historical account of the beliefs and customs of the Acagchemem (called Juaneño by the Spanish colonizers) tribe of the mission of San Juan Capistrano. Boscana’s ethnographic contribution resulted from an 1812 questionnaire sent by the Spanish government to the Missionaries of Alta California. This is published here as an appendix. Boscana died at Mission San Gabriel and is the only missionary to be interred among 2,000 other mission inhabitants, mostly Tongva-Gabrielino Indians.

The Acagchemem people dwelled along the coast in what is now Orange and San Diego counties. Many of them were baptized at Mission San Juan Capistrano in the late eighteenth century. Robinson estimated the non-Indian population of Alta California at 8,000, and the Indian population at 10,000. In 1770, the estimated aboriginal population was 133,550. The Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation is recognized by the State of California, but not yet by the federal government, preventing it from accessing, protecting and restoring their ancestral lands and sites.

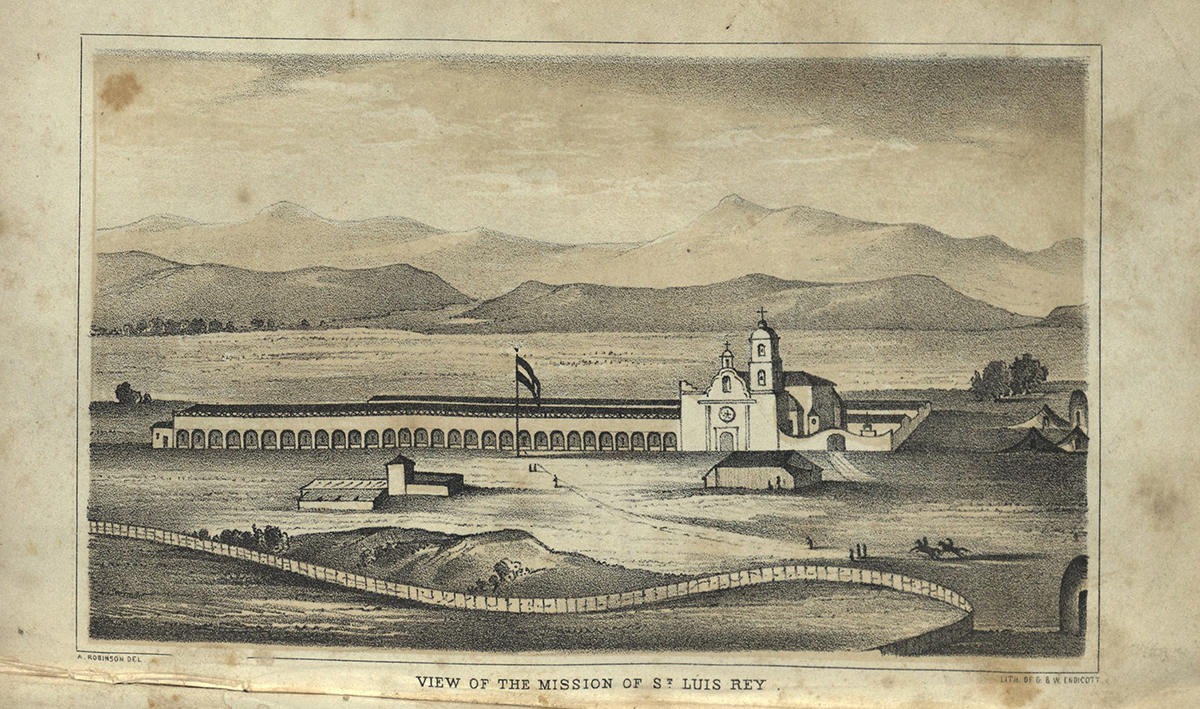

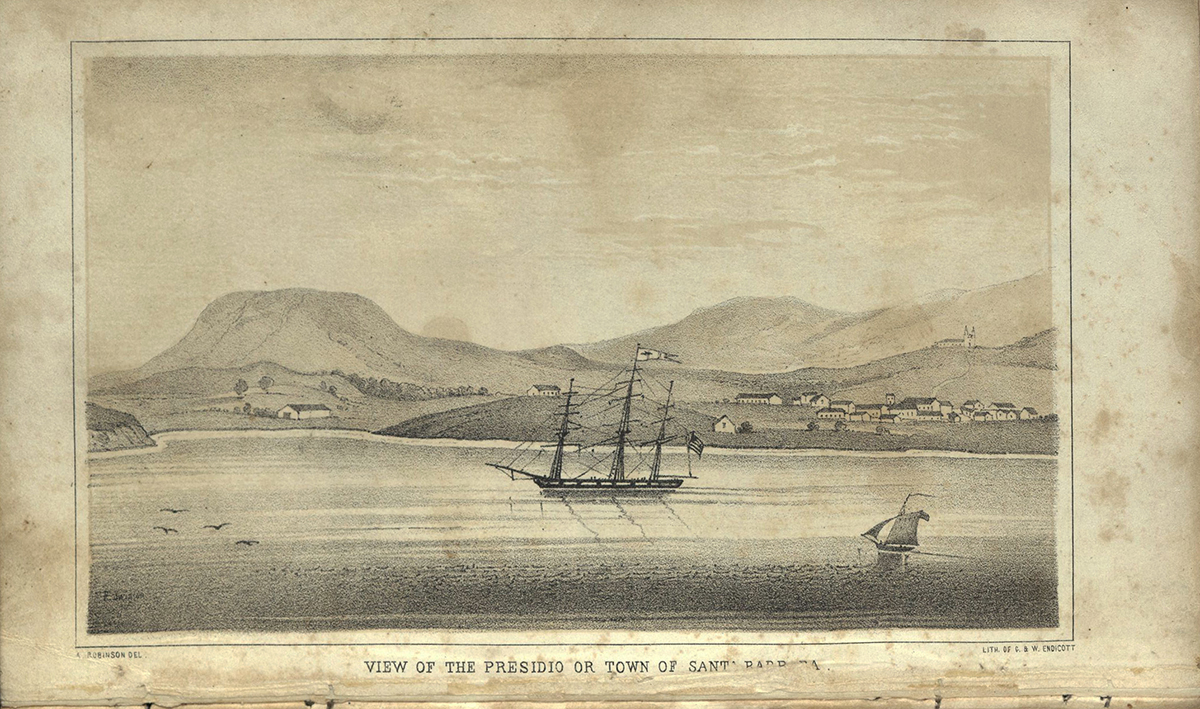

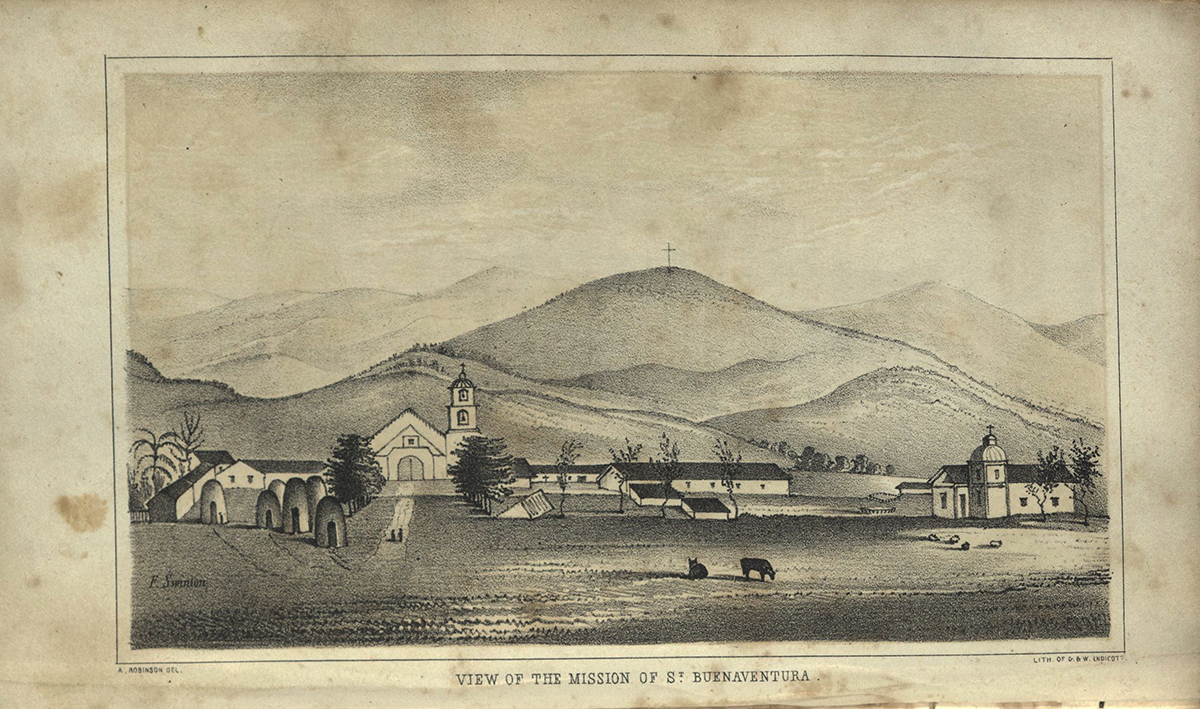

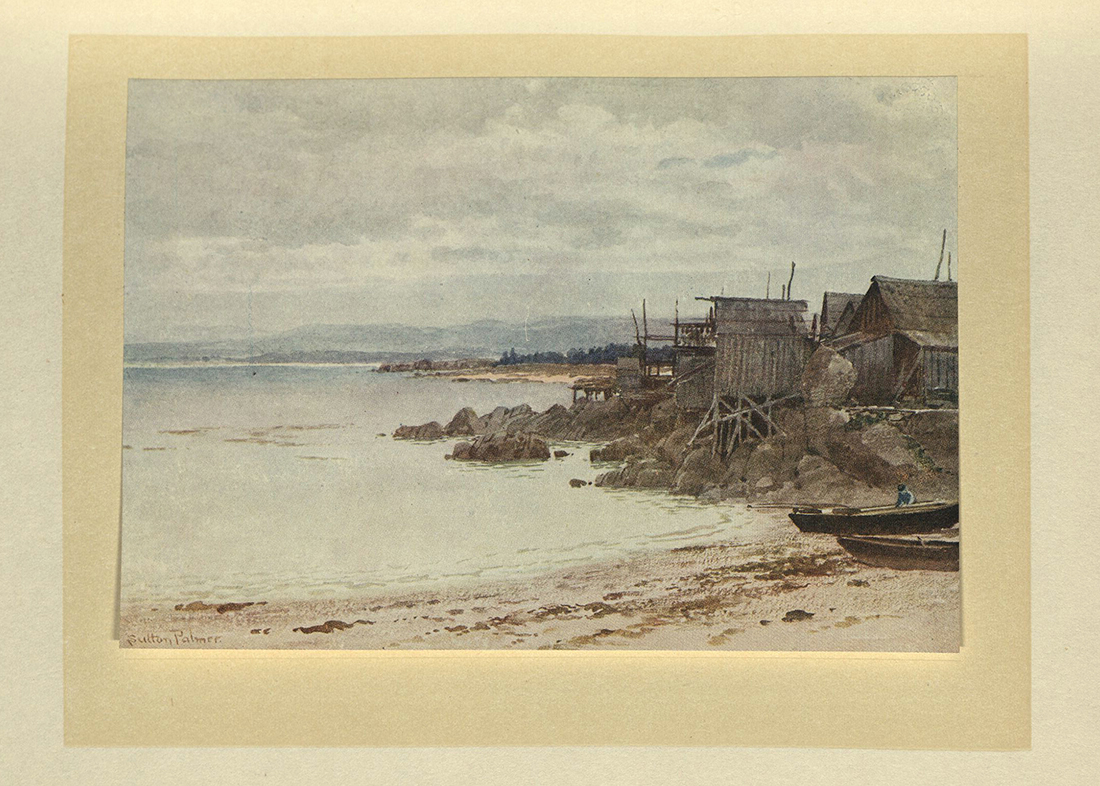

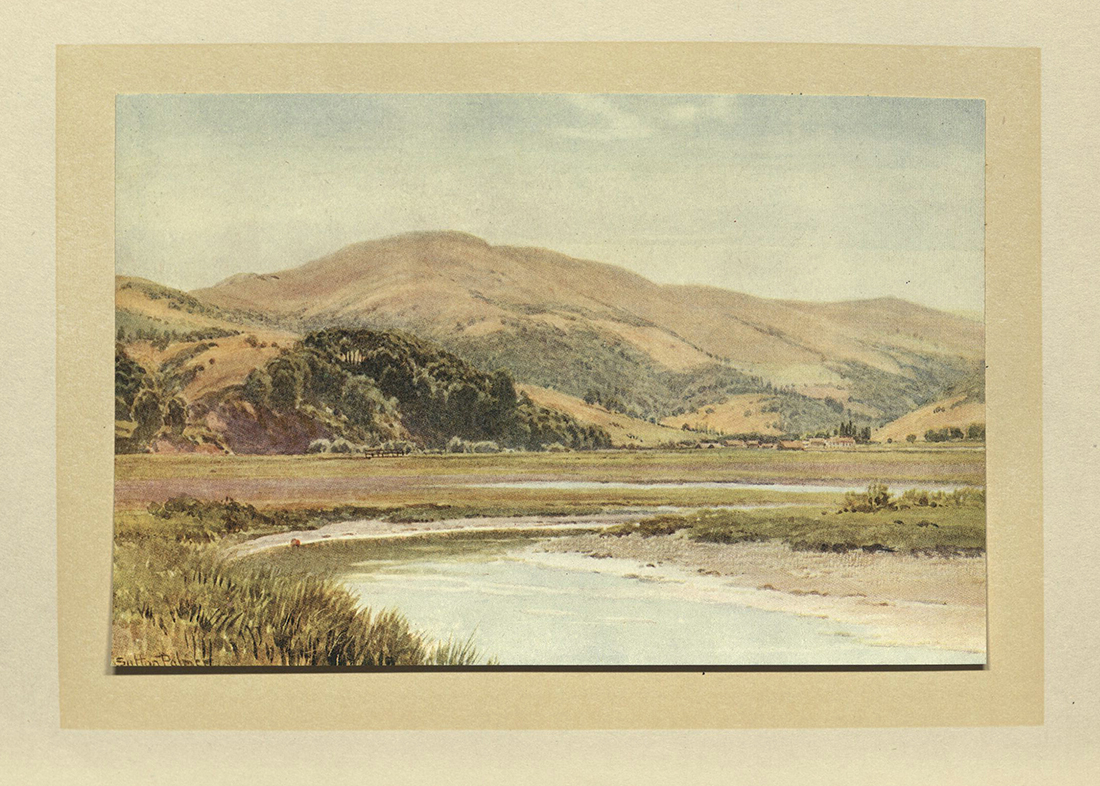

The book is illustrated with lithographs from Robinson's now-lost drawings of four California missions.

The reverend father was at prayers, and some time elapsed ere he came, giving us a most cordial reception. Chocolate and refreshments were at once ordered for us, and rooms where we might arrange our dress, which had become somewhat soiled by the dust.

Seen from the ship, the “Presidio” or town, its charming vicinity, and neat little Mission in the background, all situated on an inclined plane, rising gradually from the sea to a range of verdant hills, three miles from the beach, have a striking and beautiful effect.

… we set out on an excursion to St. Buenaventura. The road thither is partly over the hard sandy beach, and at times, when the tide is low, it is possible to perform the whole journey over this smooth level. We were not over two hours on the road, and arrived before dinner, finding the reverend father Francisco Uria closely wrapped up in his studies, in his sitting apartment.

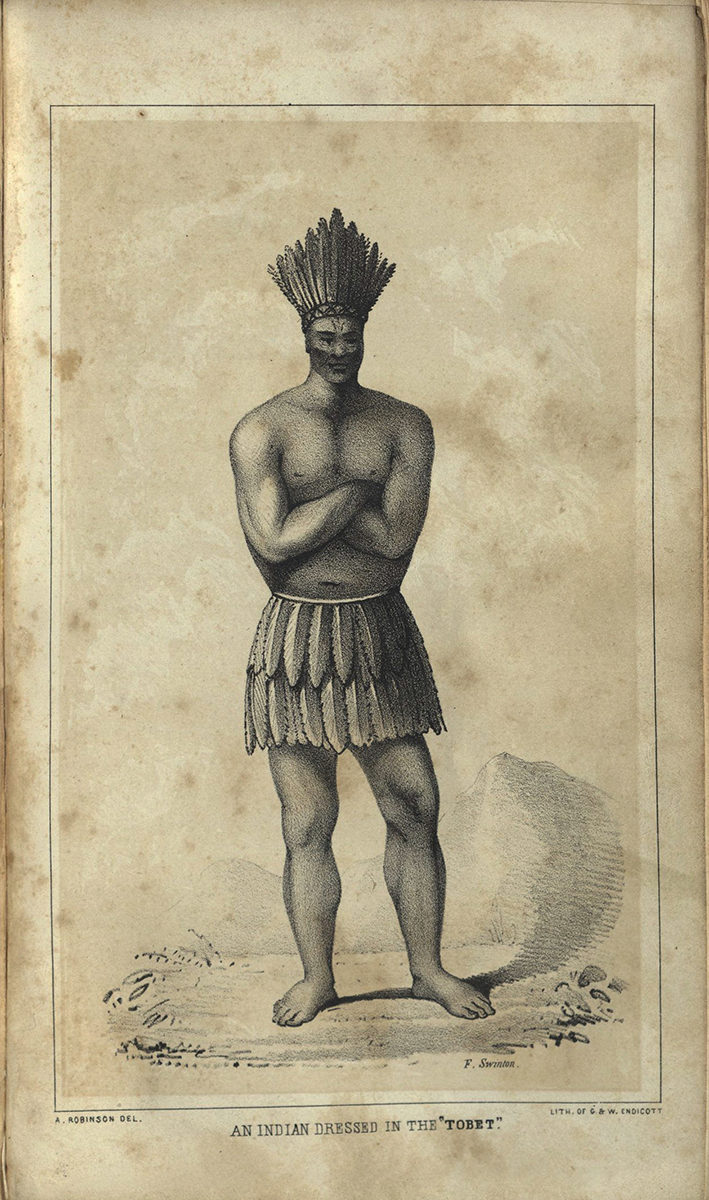

… they fixed upon the head a kind of wig, called “emetch,” that was made secure, by a braid of hair passed around the head, into which, they inserted various kinds of feathers, forming a crown, or ad they termed it, an “eneat;” then, there covering for the body, was also prepared from the feathers of different kinds of birds, which were sewed together, an like a sort of petticoat reached down to their knees – this they called a “paelt.”

They take to themselves wives, and domesticate themselves among the different tribes in the west…the result of this intermixing and intermarrying has been the springing up of a numerous hybrid race of beings, that constitute a medium, through which, it is hoped, at no distant day, the laws, arts, and habitudes of civilized life may be successfully introduced among the tribes of the west, and be the means of reclaiming them from the ignorance and barbarities in which they have been so long enthralled.

THE LOST TRAPPERS

David H. Coyner (1807-1892)

Cincinnati: J.A. & U.P. James, 1847

First edition

F592 C88 1847

This fictionalized narrative of the American West apparently had its beginnings as the now-lost journal of Ezekial Williams written between 1807 and 1809 while on an overland trapping expedition. Williams, a Missourian, was caught in the Rockies until he became a prisoner of the Kansas Indians. He was freed in 1814 and returned to the Rockies, descending the Arkansas River, where low water compelled him to cache his furs.

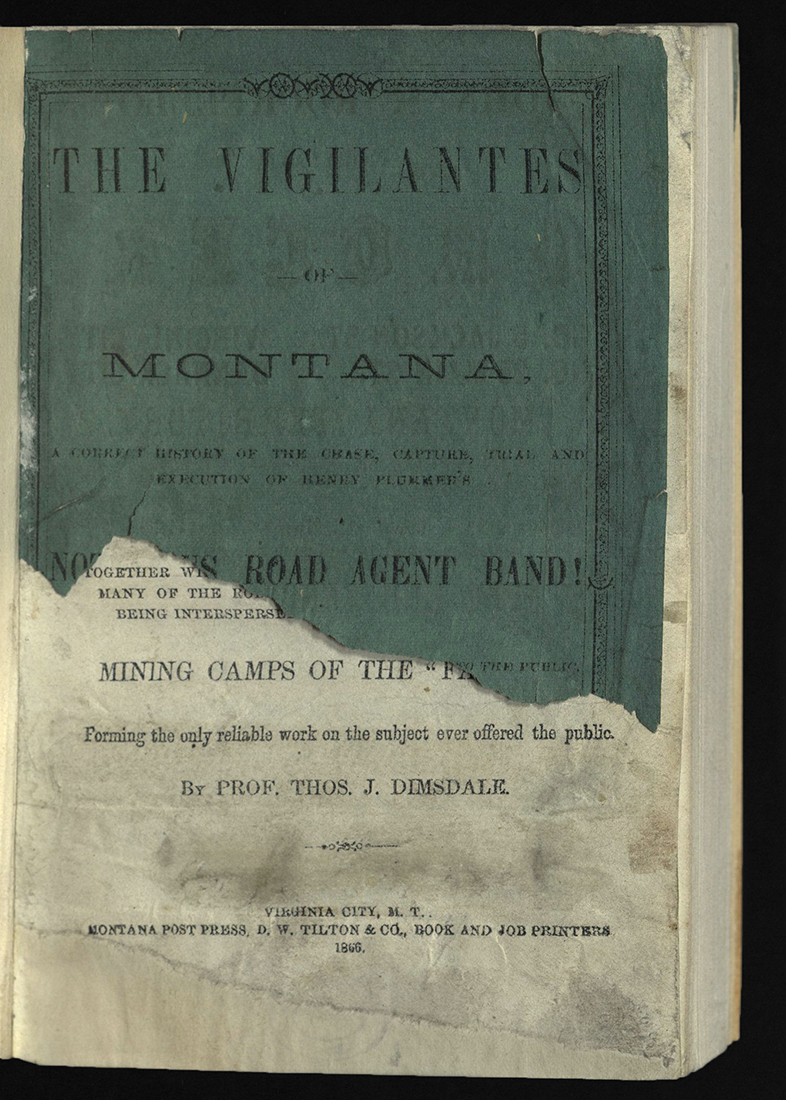

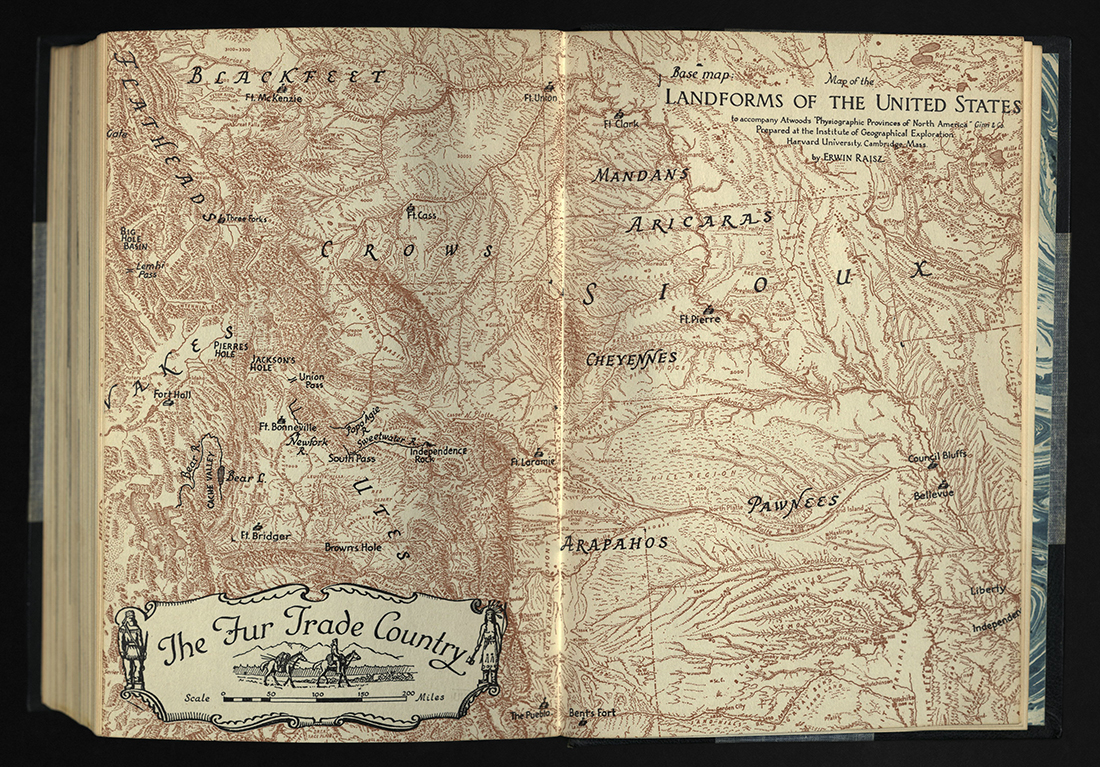

Seventeen of the twenty men who set out on the original expedition died from hunger and disease or were killed by Comanche. The survivors met Spanish traders at an outpost on the Colorado near Santa Fe and went with them to California. Williams found the Missouri and made it back to St. Louis.