Dramatis Personae

Early Print Culture and European Performance Arts

Checklist for "Dramatis Personae"

Curated by Luise Poulton, 2010

Exhibition poster designed by David Wolske, 2010

Digital exhibition produced by Alison Elbrader, 2012

Faculty Collaboration:

Prof. Christine Jones

French 4900/7900, 2006

Dramatis Personae Archive

Format udpated by Lyuba Basin, 2020

Dramatis Personae: Early Print Culture and European Performance Arts

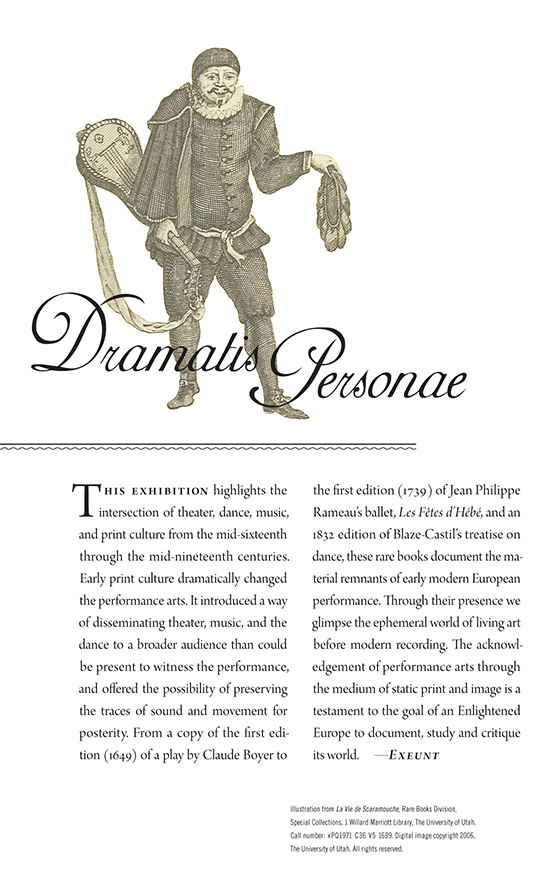

This exhibition highlights the intersection of theater, dance, music, and print culture from the mid-sixteenth through the mid-nineteenth centuries. Early print culture dramatically changed the performance arts. It introduced a way of disseminating theater, music, and the dance to a broader audience than could be present to witness the performance, and offered the possibility of preserving the traces of sound and movement for posterity. From a copy of the first edition (1649) of a play by Claude Boyer to the first edition (1739) of Jean Philippe Rameau's ballet, Les Fêtes d'Hébé, and an 1832 edition of Blaze-Castil’s treatise on dance, these rare books document the material remnants of early European performance. Through their presence we glimpse the ephemeral world of living art before modern recording. The acknowledgement of performance arts through the medium of static print and image is a testament to the goal of an Enlightened Europe to document, study and critique its world.

Utah Philharmonia

Robert Baldwin, director

Conducted by Steve Voorhees

Robert Baldwin, director

Conducted by Steve Voorhees

À Paris, chez Toussainct Quinet, au Palais, dans la petite Salle, sous la montée de la Cour des Aydes, 1649 avec Privilège du Roy

First edition

PQ1731 B74 T97 1649

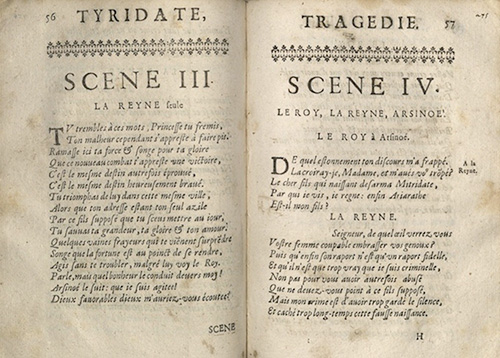

Abbot Claude Boyer, preacher and poet, also wrote plays and operas. He was a member of the French Academy. His success in the pulpit was poor. As a poet he was mocked and derided by Jean Racine and other contemporary literary figures. His tragedy, Judith, however, did meet with some success. Still, he was considered in his time and by his peers a mediocre writer. Boyer was a frequent guest of the Hotel de Rambouillet, famous in its day as one of the premier French salons. Its guests included some of the best French minds of the day, including Pierre Corneille, Moliere, Racine, Rene Descartes, Blaise Pascal, and Jean-Baptiste Lully. In 1645, Boyer dedicated the first of his twenty-two plays to Mme de Rambouillet. Tyridate is the fifth published work of Boyer.

Imprimés à Rouen, et se vendent à Paris, chez A. Covbre…et G. Lvyne.... 1661, avec Privilège du Roy

PQ1791 P6 ARC

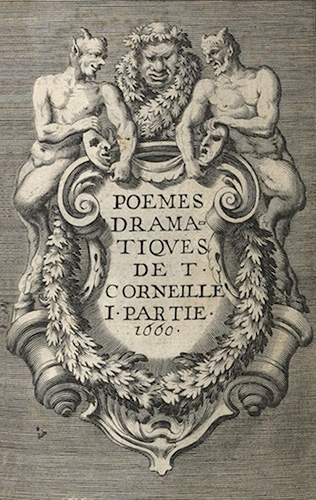

Thomas Corneille was the brother of French playwright Pierre Corneille. Although Thomas was nearly twenty years younger than Pierre, they were close all their lives, marrying sisters, living together and often working together. In spite of the near-worship of Pierre, Thomas was also recognized in his day as a great author. He wrote his first play in Latin at the age of fifteen. He wrote the longest running play of the period, Timocrate. He also wrote a play that was booed off the stage. Over a period of forty years, he wrote forty plays, in nearly every genre and in poetry and prose. His work was performed at court and in all the major theaters of Paris. Fifty years after his death, Voltaire wrote of Thomas that, “with the exception of Racine, no one compared.

London: Printed by J. M. for Henry Herringman, 1676

PR3612 S6 1687

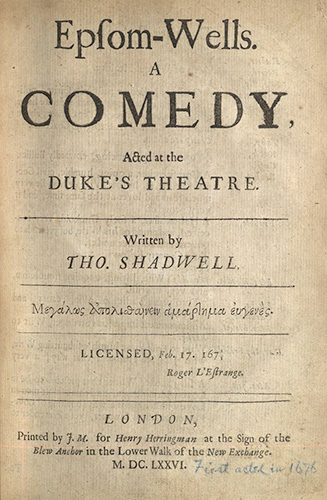

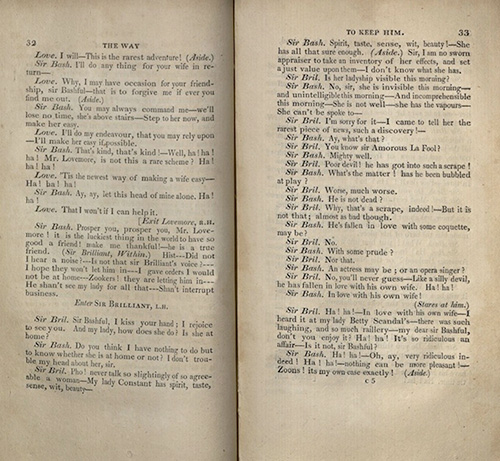

Thomas Shadwell produced his first play, a comedy, in 1668. The Sullen Lovers, written in the style of Ben Jonson, was based on a play by Moliere. Shadwell’s best-known and best-liked play was Epsom-Wells, first produced in 1672. For the next fourteen years, Shadwell produced nearly a play a year, each portraying a colorful, comical picture of contemporary conduct. Shadwell and John Dryden were on friendly terms until Dryden joined the company of the court. Shadwell, a champion of Protestantism, attacked John Dryden (1631-1700) in a satire. The result was an immediate response from Dryden with a satire of his own. The ink flew until 1688, when, because of a Whig victory, Shadwell replaced Dyrden as poet laureate. University of Utah copy bound with Otway, Thomas.

The Souldier’s fortune

. London, 1687; Otway, Thomas.

The Athiest

. London, 1687; Dryden, John.

The Indian Emperour

. London, 1686; Dryden, John.

Oedipus

. London, 1687; Dryden, John.

The Spanish Fryar

. London, 1686; Lee, Nathaniel.

Sophonisba

. London, 1687; Dryden, John.

Secret-love

. London, 1679; and Lee, Nathaniel.

Constantine the Great

. 1687.

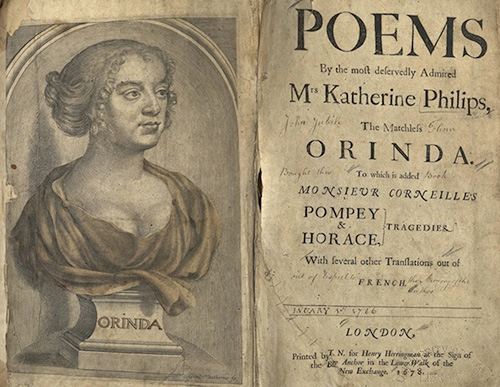

In 1663, poet Katherine Fowler Philips, daughter of a moderate Puritan and wife of a prominent Parliamentarian, translated Pierre Corneille’s tragedy La Mort de Pompée. Her translation was performed that year at Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin. The publication of Pompey was well-received and secured her reputation as an author. In 1664, a collection of her poetry plus her translation of La Mort de Pompée and her translation of Corneille’s Horace was published, much to her displeasure. She objected to the quality of the printing and the edition was removed from sale. Nevertheless, the book was reprinted in 1669, 1678 and once more in 1710.

London, Printed and are to be sold by Richard Baldwin...,1693

First edition

PN1891 R8

Thomas Rymer, famous for coining the phrase “poetic justice,” was educated at Cambridge as a barrister, but turned instead to literary criticism. The author of one play, he is better known for his attacks on English playwrights. In A Short View of Tragedy, first published in 1692, for instance, he called Shakespeare’s “Othello” a farce.

À Paris, chez Antoine Dezallier, ruë Saint-Jacques, à la Couronne d’or. 1696, avec Privilège du Roy

First edition

CT1011 P4 1696b oversize

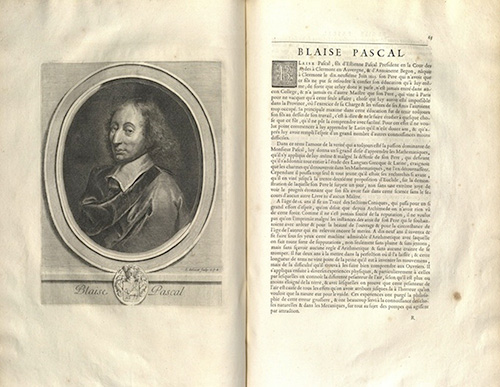

Charles Perrault’s two volume work contains one hundred eulogies with engraved portraits, fifty per volume, of famous men who had died during the seventeenth century. Hommes illustres is divided into five categories: churchmen, military leaders, statesmen, scholars and men of letters, and artists. The University of Utah copy is particularly rare, one of only a few copies containing portraits of Antoine Arnauld and Blaise Pascal – the portrait of Arnauld mounted at a later date. While the book was still being printed, Jesuits complained about the inclusion of Jansenists. Perrault and his editor, Dezallier, struggled to publish the complete edition of biographical portraits. Threatened with blackmail by the Jesuits and afraid of losing his royal pension, Perrault capitulated. The interference caused no small amount of scandal. Jean Racine purportedly wrote a now-lost poem about the incident.

Suivant la copie à Paris, Chez Charles de Sercy, au Palais, au sixiéme Pilier de Grand’Sale, vis-à-vis la Montrée de la Cuor des Aydes, à la bonne Foy conronné, 1698

PQ1715 A1 1698 v. 1 & v. 2

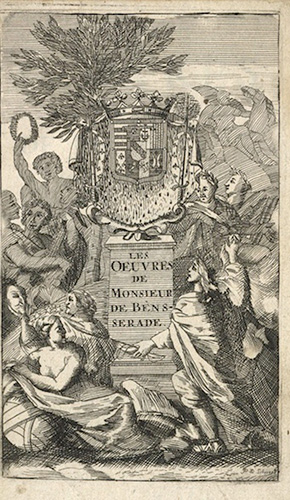

Isaac de Benserade, French poet and member of the inner circle of the court of Louis XIV, is best known as the librettist for the king’s ballets. By 1681, Benserade had choreographed twenty-four ballets de cour, including one with music composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully. Benserade also composed court masquerades. Together with Pierre Corneille, he was considered one of the leading French poets of his day.

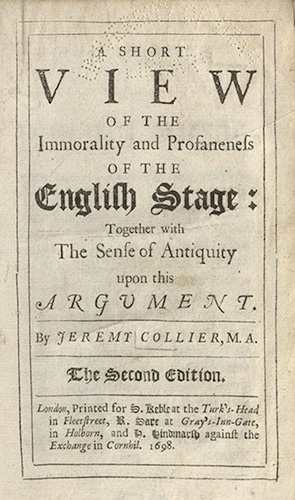

London. Printed for S. Keble...,1698

Second edition

PN2047 C6

Jeremy Collier was an English clergyman who supported James II. He is best known for his combative anti-theater pamphlet, mostly directed toward the plays of William Congreve and John Vanbrugh. Collier charged that these plays lacked exemplary morality. He described all the characters as wicked and denounced the playwrights for failing to punish them. He objected to exclamations such as, “Heavens!” Collier’s little tract created a pamphlet war, including a lengthy and serious refutation from Congreve and a brief, casual response from Vanbrugh, who charged Collier with being more sensitive to unflattering portrayals of the clergy than to profanity.

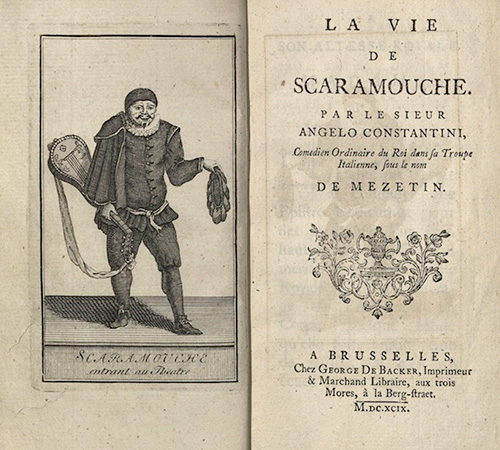

À Brusselles, Chez George de Backer, Imprimeur & Marchand Libraire, aux trois Mores, à la Berg-straet, 1699

PQ1971 C36 V5 1699

Scaramouche was the stage name of Italian actor Fiorillo Tiberio (1604?-1694). He worked with several small theatrical troupes. His most famous role was that of “Scaramuccia” in Il Convitato di Pietra. He was famous for his strength, agility, and gracefulness. He had a remarkable gift for pantomime and improvisation as well as a superb voice. He was also a talented flautist. He was so revered as an actor that his child was baptized in Rome by Cardinal Chigi who represented Pope Alexander VII. His fame for his role as Scaramouche spread quickly. In France he was invited to perform before Anne of Austria and at the Court of Louis XIII. He was also a favorite of Louis XIV. Tradition has it that Molière never missed a performance by the great actor and that he used Scaramouche as a model when he himself performed.

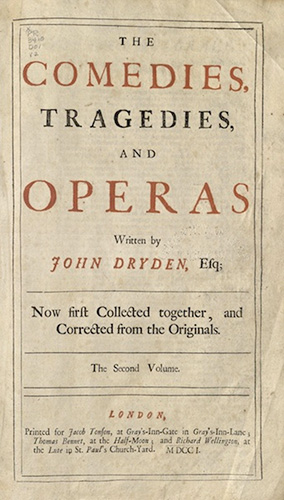

London: Printed for Jacob Tonson, Thomas Bennet and Richard Wellington, 1701

First collected edition

PR3410 D01 v. 1 and v. 2 oversize

Poet and playwright John Dryden was the leading English literary figure of the latter half of the seventeenth century. His work as a whole paints a vivid political, religious, and philosophical portrait of his era. Dryden studied works from classical Greece and Rome, Renaissance England, and contemporary France. It was his genius to take elements from each of these and from them produce a new and relevant repertory in British drama.

London, printed by R. Tookey, for Rich. Parker, 1703

First edition

PR3605 O5 G6 1703

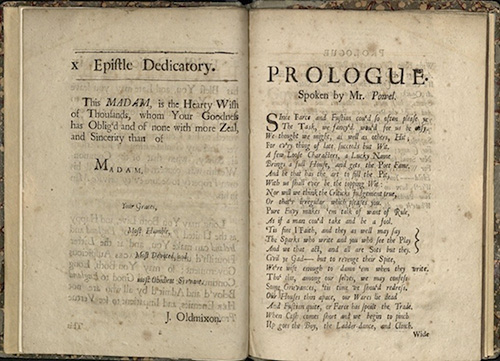

John Oldmixon is best known for his histories, particularly his Critical History of England (1724-1726). This work caused controversy, especially in its defense of Bishop Gilbert Burnet. Oldmixon began his writing career as a poet and dramatist. His first publications were plays. Poverty turned Oldmixon’s pen from poems and plays to political pamphlets and newspaper columns. He was hired by one newspaper to counteract the views of Jonathan Swift, Daniel Defoe, and Alexander Pope, who included him in The Dunciad (1728). He was not adequately compensated for his efforts. He spent much time appealing to publishers such as the large firm of Jacob Tonson, for funding. His lifetime output, then, is indicative of the girthed Muse met by most professional writers of his day.

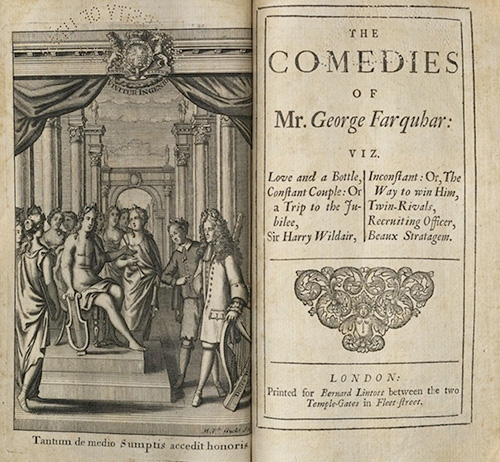

London: Printed for Barnard Lintott, between the two Temple-Gates in Fleet Street, (1707)

First collected edition

PR3435 A1 1707

Irish playwright George Farquhar began his career in the theater in Dublin as an actor. While performing in John Dryden’s The Indian Emperor, he accidently but severely wounded a fellow actor in a sword fight scene. Farquhar foreswore acting for the rest of his life. He moved to London at about the same time that his friend, the well-known actor Robert Wilks did. Wilks encouraged him to write. Farquhar’s first play, a comedy, was produced in 1698.

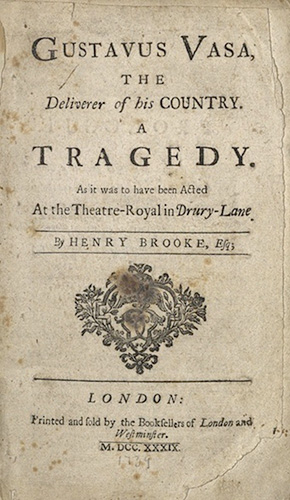

London: Printed and sold by the Booksellers of London and Westminster. 1739

PR1243 B75 1710

This sammelbande is made up of seven plays, printed between 1710 and 1747. The plays include Gustavus Vasa by Henry James Brooke (1771-1857), The Fair Penitent by Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718), The London Merchant by George Lillo (1693-1739), Busiris by Edward Young (1683-1765), and others. A sammelbande is a collection of various editions of thin books or pamphlets bound together in a single volume. In some cases, the author of these pieces is the same; in others, the subject matter dictates the grouping. Still other sammelbande appear to be random. The word “sammelbande” used to describe these collections is limited to pre-eighteenth century printings. At this time, before the advent of the modern newspaper and magazine, short political and religious essays, plays and poetry appeared in profusion as an inexpensive means of spreading information, opinion and entertainment. Bookbinding during this period was costly. Readers often economized by binding several pieces together. The pieces thus bound can reveal a great deal about a reader’s interests and the ways in which early printed books were purchased, used and saved.

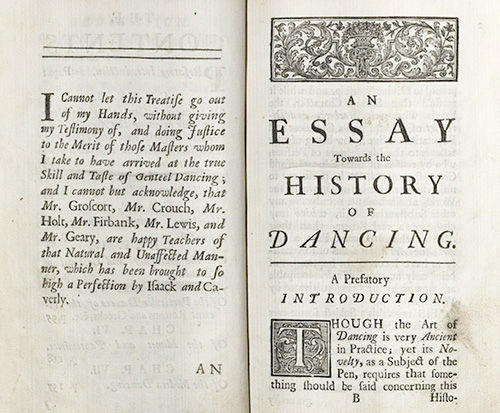

London: Printed for Jacob Tonson at Shakespeare’s-Head over-against Catherine-street in the Strand, 1712

First edition

GV1601 W36 1712

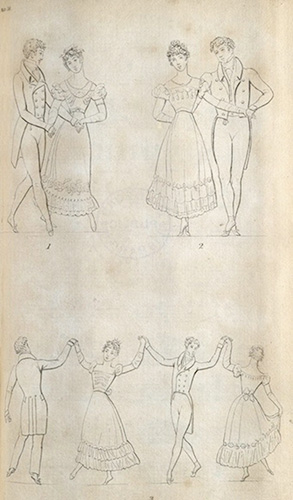

This is the earliest history of dancing in English, written by the son of a dancing master of the same name. Young John Weaver studied Latin and Greek and would pepper his later works with classical quotations in their original languages. Indeed, one of Weaver’s ambitions was to revive the style of acting and dancing of the ancient Greeks and Romans. In 1700 he staged his first production, describing it as “the first Entertainement that appeared on the English Stage, where the Representation and Story was carried by Dancing, Action and Motion only.” During this same time, a new system of dance notation had been published in Paris: R.A. Feuillet’s Chorégraphie. Weaver translated Feuillet into English and published the translation in 1706. That same year he also published A Collection of Ball-Dances Performed at Court, in which, by using Feuillet’s notation, he documented the dances created by Queen Anne’s Royal Dancing Master, Mr. Isaacs. A dancer himself, Weaver taught dance until he died at the age of eighty-seven.

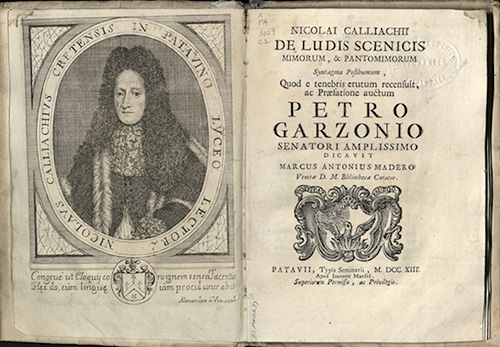

Patavii, Typis Seminarii, 1713 Apud J. Manfr’e

First edition

PA3029 C2

Born in Crete, Nicholas Kalliakis moved to Italy at an early age. He served as professor of Greek, Latin and philosophy at Venice in 1666 and as professor of belles-lettres and rhetoric in Padua in 1667. There he began his study of dance in classical Greece and wrote this, his principal work, published posthumously.

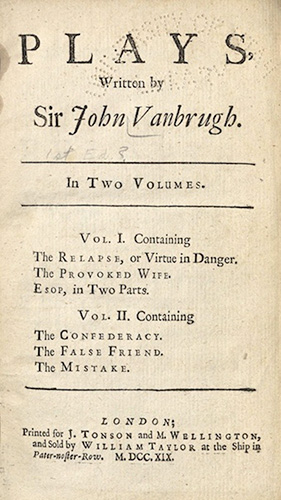

London : Printed for J. Tonson and M. Wellington, and sold by William Taylor, 1719

PR3737 A1 1719 ARC

English dramatist John Vanbrugh is better known today as the architect of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire and Castle Howard in Yorkshire. His comedies were favorites of the Restoration period but also caused controversy. They were deemed sexually explicit and, worse, defended a woman’s rights within marriage. Jeremy Collier attacked Vanbrugh and his views in Short view of the immorality and profaneness of the English stage…

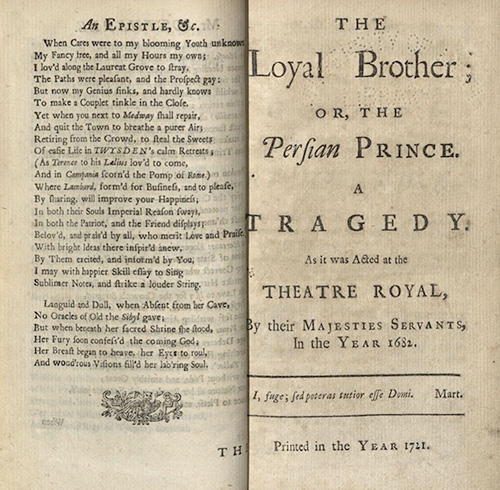

The first edition of Irish poet Thomas Southerne’s collected works was printed in 1713. Southerne based his first play, The Persian Prince, on a contemporary novel. The play was a thinly disguised political allegory, which included a very flattering portrait of James II in the form of one character. First produced in 1682 with the help of John Dryden, who wrote the prologue and epilogue, the play was, nonetheless, not particularly successful. After the Glorious Revolution (1688/9), during which Southerne held the rank of captain in Princess Anne’s regiment, he devoted himself to dramatic writing. His 1694 The Fatal Marriage, based on Aphra Behn’s novel, and to which he added a comic element, was a great success. Another success came from another novel by Behn, Oroonoko. The 1688 novel’s main character was Imoinda, an African slave and one of the few representations of black women in early modern literature. However, Southerne changed Imoinda’s skin color from black to white.

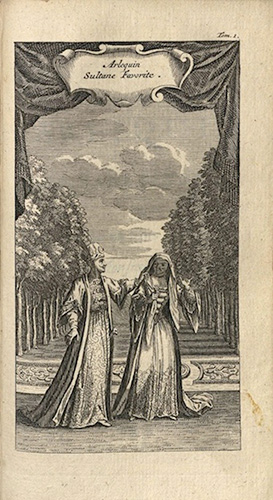

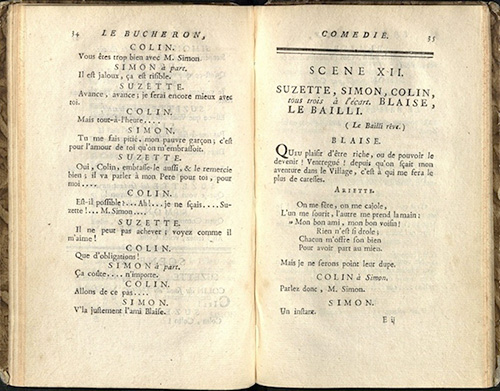

Beginning in 1684, under the favor of the Abbé de Lyonne, Alain-René Le Sage began translating a number of plays from Spanish. The translated plays were unsuccessful in French theater, but a short original farce, published in 1707, won Le Sage acclaim and began his career as a playwright and novelist. In spite of the popularity of his work, the Théâtre Français was unwelcoming and in 1715, Le Sage began to write for the Théâtre de la Foire. He collaborated in writing nearly one hundred plays. Théâtre de la Foire (fairground theater), was comic opera held in outdoor booths at festival time. It enjoyed great popularity among both the nobility and the commoners of Paris. Much of Le Sage’s inspiration came from his keen sense of Parisian society, which he used to advantage in picturesque scenes and adventures.

À Paris, Chez d’Houry fils... 1724 avec Privilège du Roy

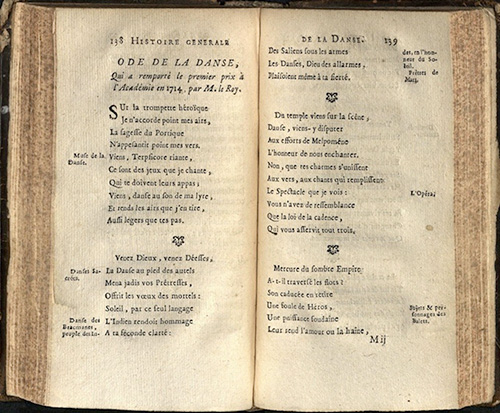

GV1601 B71 1724

Jacques Bonnet described the dances of antiquity, listed the ballets performed at European courts between 1450 and 1723, and described several of these in detail. The treatise was put together from the manuscripts of Pierre Bourdelot, and it was itself later regarded as an authoritative source by Louis de Cahusac and others.

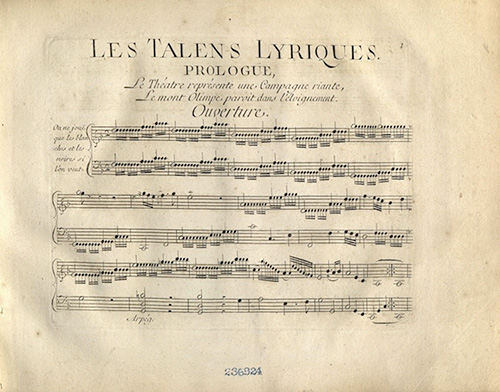

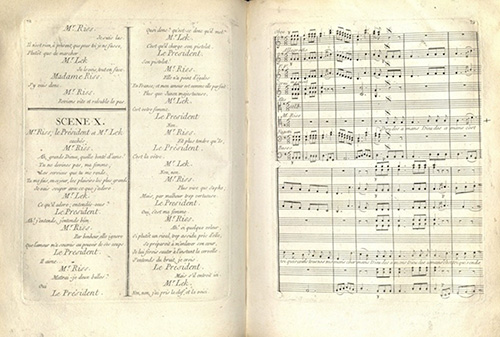

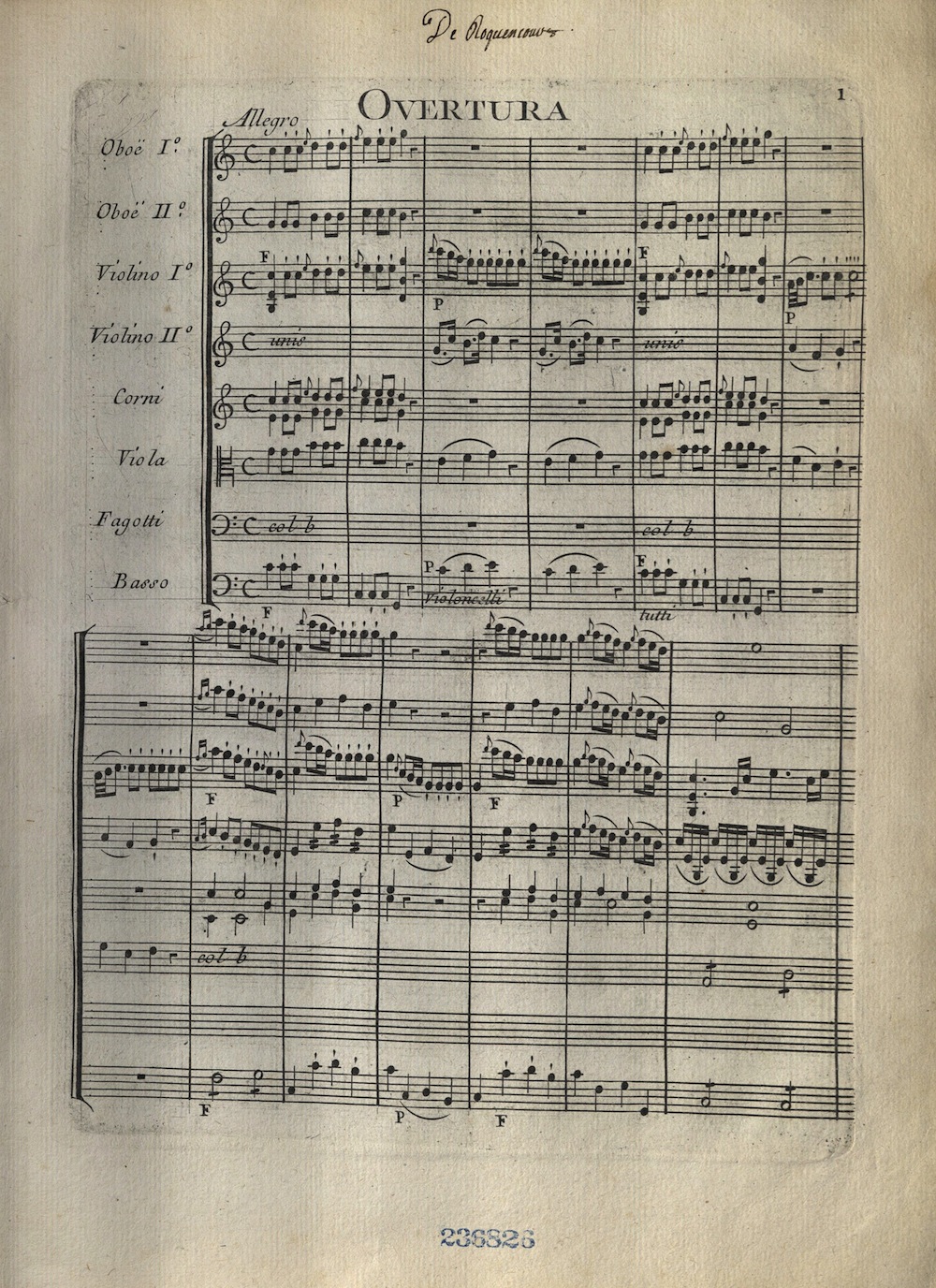

À Paris: Chez l’Auteur..., La Veuve Boivin..., M. Le Clair... Avec Approbation et Privilège du Roy, (1739)

First edition

M1502 R3 F4

Jean Philippe Rameau became perhaps the most lauded composer in his day and is the most recognized composer of his era today. He established himself first as a theorist, but his love was for the stage, which he turned to at the age of fifty. Les Fêtes d’Hébé was first performed at the Paris Opera on the 21st of May, 1739. The loose storyline follows Hébé’s distaste for the amorous goings-on of heaven and her determination to find out whether the situation isn’t better on Earth. The piece, Rameau’s fourth work for the stage, was a great success, a musical painting a la Watteau’s shepherds, sylvans, and fauns – highly ornamented and graciously stylized. Les Fêtes was performed nearly four hundred times after its premiere.

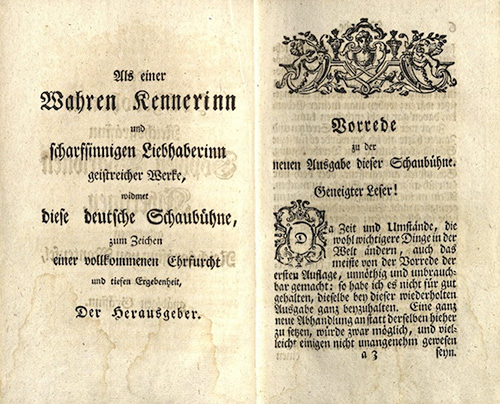

Leipzig: B.C. Breitkopf, 1746-1750

Neue verb. Aufl.

PN6114 G48 1746

The works of Johann Gottsched helped develop the purification of the German language. Gottsched’s intent was to reign in excessive and vulgar German literary tastes of the time. His concern was justified, but others rejected this attempt, objecting to artificial rules and championing the cause of imagination. Gottsched stood his ground but was defeated. Before the end of his life he was mocked and sneered at for being doctrinaire. Later critics of Gottsched agree that early modern German theater owed more to him than his contemporary critics gave him credit for. Gottsched wrote several plays, including adaptations of English and French tragedies. Deutsche Schaubühne, is a six volume collection of drama, mostly translations of French plays. The second edition, with its new preface, was the culmination of Gottsched’s life work.

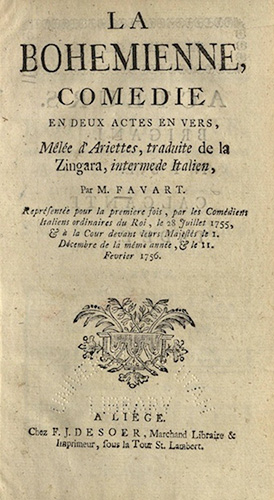

À Liege, F. J. Desoer, Marchand Libraire & Imprimeur, sous la Tour St. Lambert. (175?)

M1500 F37 B65

Little is known about Neapolitan composer Rinaldo di Capua, although at least forty operas are attributed to him, produced in Florence, Venice, Rome, Lisbon, Turin, Paris and other cities. Music for only six of his operas survives. La Bohemienne was, perhaps, first performed at the Academie Royale de Musique in Paris in June, 1753, by a small company of Italians. It was so successful that the score was published soon after with Italian words. In 1755, two more characters were added for a performance in Italy. Soon after this, the work was adapted by Madame Favart, produced with her in the principal role. It is likely that considerable changes were made to suit very particular French tastes. Charles Burney, a contemporary traveling musician who later turned music historian, found di Capua in Rome in 1770. Di Capua had hoped to publish his operas as a collected work to help him in his old age, but his son had burned all his manuscripts. Rinaldo di Capua, with a few minor hits on his hands, died in poverty and obscurity. However, he contributed a key innovation to the structure of the modern symphony. In his own compositions, he replaced the usual suite of vignettes, which could be moved from one place to another in any given performance, with a form that was played and heard as a coherent whole – that is, a single narrative of parts, instead of a group of separate parts put together with no real attachment to one another. According to Gurney, di Capua used this approach when composing his opéra comédie.

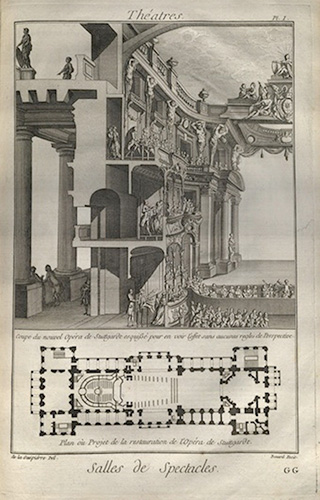

ENCYCLOPÉDIE…

Paris: Braisson, 1751-65

First edition

Denis Diderot said that the purpose of his Encyclopédie was “to change the common way of thinking.” And to a large degree, he did just that. Many of the finest thinkers of eighteenth-century France contributed to this monumental project, including such greats as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Jacques Rousseau, and the eminent mathematician Jean d’Alembert. What made the Encylopédie important was that it embodied a new approach to knowledge, based upon the new methods and theories of Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton. Diderot and the other Encyclopedists refused to accept the authority of political power or religion in questions of the intellect or of art. Far from being a neutral compendium of useful knowledge, the Encyclopédie was, tantamount to a political manifesto, an attempt on the part of radical French intellectuals to establish their own authority by virtue of their superior reason. They allowed nothing in the work that was not known through empirical study. Published separately, each volume became an immediate success. The French court, judiciary, and church, however, were outraged by the project and what it stood for. In 1759, the seven volumes that had appeared to date were banned by the government and placed on the Index by the Pope. For the next twenty years, Diderot carried on, writing countless small articles and many major ones, while dealing with the continuous attacks of critics. It is hard to imagine such a substantial work as an “underground” publication, but that, indeed, was what it was. The Encyclopédie promoted an idea of knowledge and learning in the arts and sciences that was to become the dominant characteristic of the modern age.

À La Haye, Chez J. Neaulme, 1754

First edition

GV1600 C2 1754

Louis de Cahusac was a librettist who worked with dramatists and musicians such as Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764). He also contributed to Diderot’s Encyclopédie. In this treatise, Cahusac stressed the importance of studying the theories of all the arts and placing dance in the aesthetic context of the performing arts. Volume one is a history of the dance of ancient and Middle Eastern civilizations. Cahusac relied on the vast literature available to him in classical studies. He contributed new information by presenting an original treatment of dance from the perspective of neo-classical aesthetic philosophy. He paid special attention to Roman pantomime, which he saw as a source of renewal for a decadent academic theater. He argued for the place of pantomime in dance as a discipline for the “imitation of nature.” Volume two describes the renaissance of the arts and the origins of ballet to 1610, in particular the story of dance in France from Catherine de’ Medici to 1643. Cahusac included a discussion of the history of festivals and public ceremonies. Volume three focuses on the establishment of French opera and dance in the court of Henry IV. Cahusac discussed the state of ballet in his own day with many references to persons and events in the thriving Parisian theater. His discussion included comments on theatrical allusion, stage machinery, and the principles of choreography. Cahusac borrowed from other writers but his work was a very early attempt at a comprehensive, complete history of dance.

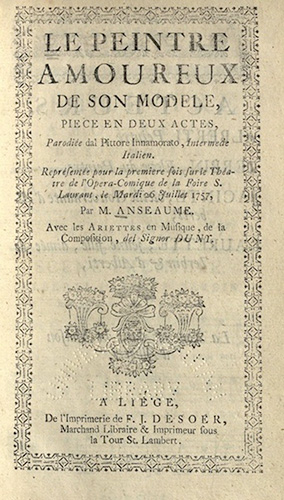

À Liége,De l’Imprimerie de F. J. Desoer, Marchand Libraire & Imprimeur sous la Tour St. Lambert, (1757)

M1500 D85 P45 1757

Edigio Romualdo Duni’s music education began with lessons from his father and sisters. He then attended a music conservatory near Naples, where he worked with Giovanni Battista Pergolesi and other Italian masters. His first successful opera was performed at the Rome Carnival in 1735. He soon left for London where he produced several operas, returning to Italy in 1749 as maestro di cappella in Parma in 1749. The Painter in Love with his Model, in two acts, was first performed at the Théâtre de la Foire Saint-Laurent in Paris on July 26, 1757. The libretto was written by Louis Anseaume (d 1784?). Duni traveled to Paris to see the premiere and stayed in France for the rest of his life. There, he helped to develop the early form of opéra comique.

À Paris,Chez Duchesne, Libraire, rue Saint Jacques, au-dessous de la Fontaine Saint Benoît, au Temple du Goût, 1757, Avec Approbation et Privilège du Roi

M1500 P54 F4

Francois Danican Philidor came from a talented musical family, including his parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins. He began his musical education while a page-boy at Versailles, where he began singing with the Royal choir of Louis XV. During this time he also learned chess. A few of his early musical compositions were performed at Versailles, although he supported himself as a young man by copying and teaching music. In 1745, stranded in the Netherlands, he played chess to make his living. British officers escorted him to London where he established his reputation as the best chess player in Europe. A decade later he returned to Versailles to apply for the position of court composer, but he was turned down because his work was considered “too Italian.” Ironic, since he was known for his aggressive chess playing in the Italian school. Nevertheless, Philidor established a fairly successful career as a composer of comic opera. Eventually, however, discouraged by the greater success of others, he returned to a career at chess.

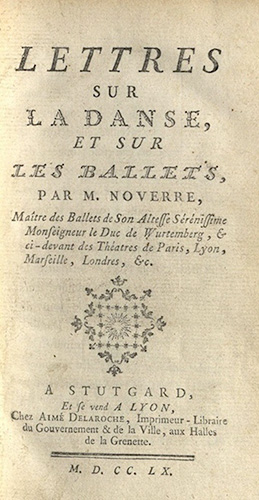

À Stutgard, et se vend à Lyon,: Chez Aime Delaroche, Imprimeur-Libraire du Governement & de la Ville, aux Halles de la Grennette. 1760

ML3460 A2 N94 1760

With Lettres, a history of dance, Georges Noverre attempted to reform eighteenth-century theatrical dance. Noverre suggested changes in stage costume, emphasized the value of good music, insisted that ballets be designed to express a specific theme and proposed the restoration and development of the art of mime. Noverre produced ballets not only in Paris (where his most illustrious pupil was Marie Antoinette), but also in Potsdam, London, Stuttgart, Lyons, Vienna, and Milan.

CHORÉGRAPHIE, OU L’ART D’ÉCRIRE LE DANSE…

À Paris, s.n., 1763

GV1590 F48 1763

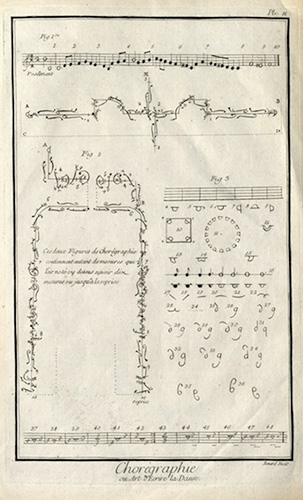

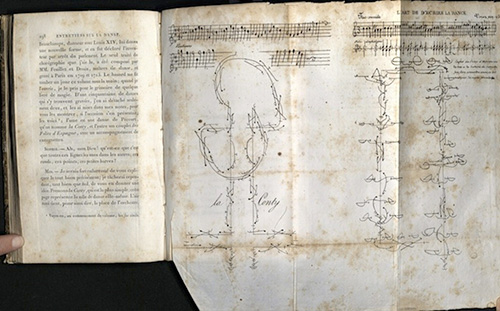

Leaf and two engraved plates from Diderot’s Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Paris, 1763. The plates, after Bernard, show Feuillet’s system of choreography, the first with seventy-six figures; the second with music and two elaborate dances.

A Paris, Chez Claude Herissant, Imprimeur-Libraire, rue Neuve Notre-Dame, à la Croix d’or. 1763. Avec Approbation

M1500 P55 B83

À Paris,Chez Antoine Boudet, Imprimeur du Roi, rue S. Jacques, à la Bible d’or. 1769. Avec Approbation, et Privilège du Roi.

First edition

ML3920 G18 1769

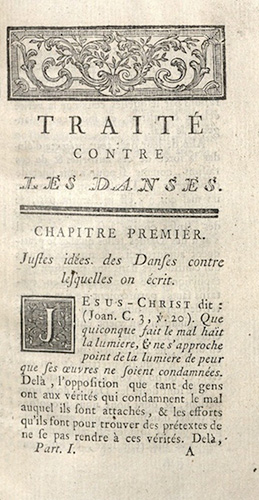

A curate at Savigny-sur-Orge, François Gauthier, in Traité contre les danses… condemned dancing and music as morally reprehensible. Dance and music were not the only things wrong with Gauthier’s world. He wrote another treatise condemning extravagent clothes, love of jewelry and luxury in general. Someone was listening. His treatise against dance and music was reprinted in 1779.

London: Printed for the author... (1770)

GV1590 G25 1770

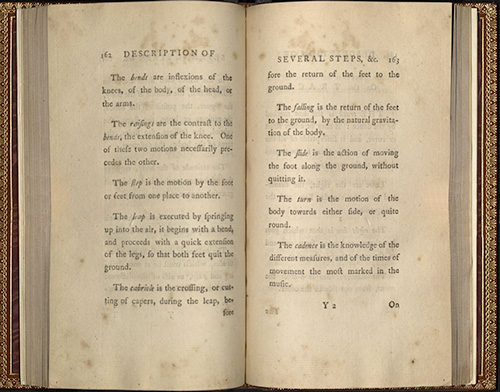

Giovanni-Andrea Gallini was director of the Kings Theatre in London. In Critical Observations, he promoted the use of contemporary dance terminology. The first two chapters contain a history of dance which is largely indebted to Cahusac’s La danse ancienne et moderne, although without acknowledgement. Chapter three, “On the air and port of the person” summarizes the positive traits a student acquires from learning how to dance: a head erect without stiffness, a body upright without affectation, a gait firm and assured without heaviness, a bearing light and airy without indecency. A poem in celebration of Mr. Marcell, Gallini’s master, is appended. A “Description of several steps and movements practiced in the art of dancing” describes the ballroom, provides a glossary, explains floor patterns, illustrates the true and false positions, comments on a few steps, and denigrates the use of chorégraphie, or dance notation.

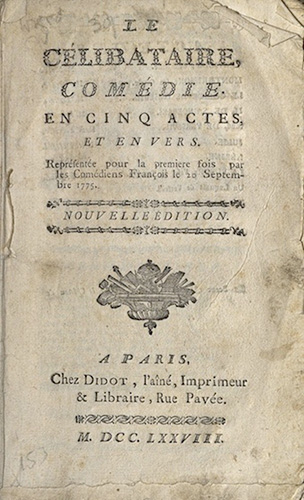

À Paris, Chez Didot, l’aîné, Imprimeur & Libraire, Rue Pavée. 1778

Nouv. Ed.

PQ1981 D35 C4 1778

Claude Dorat came from a family of attorneys, a profession he rejected. He joined the Corps of the King’s Musketeers and after leaving that, turned to the life of a writer. An early work, Réponse d’Abailard à Héloise, became quite popular. Dorat continued to write heroic epistles, light verse, comedies, fables, and novels, none of which were very good. He tried to conceal his failure by paying for expensive, lavishly illustrated publications of his own work. He would buy large numbers of seats to his plays in an attempt to hide the inevitable flop. In the end, Dorat drew fire from all directions and was equally disliked by the philosophes and their arch-enemies.

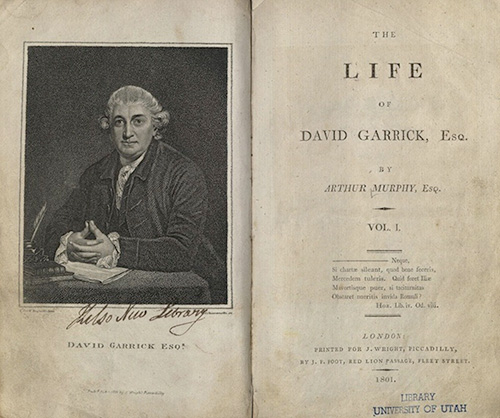

David Garrick (1717-1779) studied for a short time under Samuel Johnson before they both went to London. Garrick began his passionate career with the stage as a drama critic and a playwright. He began acting in 1741 and became an instant sensation. In 1747, he went into partnership to buy the theater at Drury Lane, and went on to make the theater a popular success, introducing more authentic costumes and stage settings. Garrick continued his acting to rave reviews. Although he continued to manage the Drury Lane theater, Garrick stopped acting in 1766. Garrick’s biographer, Arthur Murphy, was an Irish attorney, journalist, actor playwright, and biographer. He began work at a merchant’s counting-house on the recommendation of his uncle in 1747. After refusing to go to Jamaica for the merchant, and thereby alienating his uncle, Murphy went to London. In 1754 he began acting, playing the title roles of Richard III and Othello. He wrote more than twenty plays. His first play, The Apprentice, was performed at Drury Lane in 1756. Murphy’s plays were almost all adaptations from the French, and very successful, earning him fame and fortune. His career illustrates the precarious financial and legal situation of dramatic authors in Georgian England. He worked and wrote at a time when the English theater was redefining the playwright’s position within the burgeoning culture of print. Murphy spent his entire life as a playwright and barrister addressing the professional status of the dramatic author. His greatest success in this endeavor came from his play, Hamlet, with Alterations, a parody of David Garrick’s radical adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Although the play was not produced or published in Murphy’s lifetime, it changed the conversation about the bond between a dramatic author and the dramatic text as product.

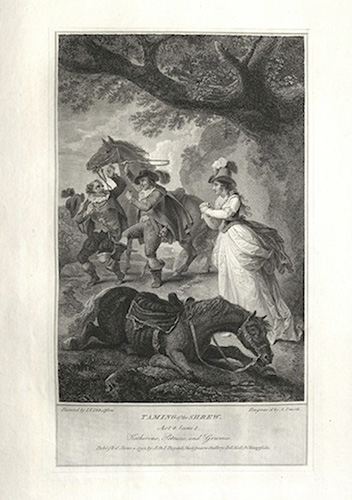

English print publisher John Boydell studied engraving in London. It is as the publisher of works of other engravers, however, that he is best known. In 1786 he began a subscription publication of engravings illustrating Shakespeare’s plays. The leading English artists, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, Benjamin West, and Henry Fuseli, were commissioned and a gallery was built by Boydell to house the works. The engravings were so popular that they became set in the public mind. The paintings commissioned by Boydell were used repeatedly to illustrate the works of Shakespeare, appearing in modified, adapted, and borrowed forms in engravings and drawings for subsequent publications. Because of financial reverses, due chiefly to the French Revolution and consequent closing of the continental market, the collection was sold by lottery in 1804.

London: Published for the Proprietors, by W. Simpkin and R. Marshall... 1818

PR3605 M9 A78 1818

Milan, 1820. Chez Joseph Beati et Antoine Tenenti

First edition

GV1787 B56 1820

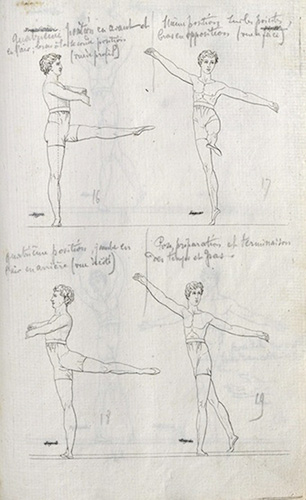

Carlo Blasis, dancer, choreographer and dance theoretician, was born in Naples. When he was young, his family moved to Marseilles. His father, who came from a long line of naval officers, was a well-established musician and composer. Blasis went to Milan where he established his career at La Scala. He danced all over Italy and in London. He married Annunziata Ramaccine and danced with her until a leg injury forced him to abandon his career as a performer. In 1837, he was made Director of the Imperial Academy at Milan, where he taught Carlotta Grisi and Fanny Cerrito, both already established stars of the dance. He published his first work, and the first codified analysis on ballet technique, Traité, and continued to write on the technique, theory and history of dance for the rest of his life. He is best known for developing the attitude position, based on the statue of Mercury by Geovanni da Bologna. He developed the technique called “spotting,” which prevents dizziness while performing turns. He taught Enrico Cecchetti, who would later expand Blasis’s technique and would become famous for ballet instruction that is still used.

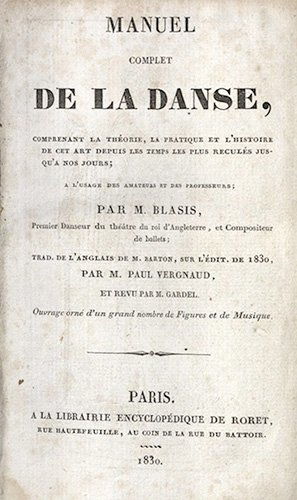

Paris.: À la Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret, rue Hautefeuille, au coin de la rue du Battoir, 1830

ML3420 B64 1830

Carlo Blasis wrote on the theory of dance, pantomime, and the composition of ballets. Manuel is a comprehensive survey of ballets of the early nineteenth century. He also wrote on social dancing, which he called “private dancing.” Blasis founded the Italian school of ballet technique, based on his theories of equilibrium and balance. His The Code of Terpsichore played a fundamental role in the history of ballet. The sequence of exercises he introduced in this book became the basis for modern ballet classes. The English edition was translated by R. Barton. A frontispiece of Terpsichore was engraved after Canova and there is also a portrait of Blasis. The edition contains eighteen plates of dance positions, and twenty-two engraved plates of music by Carlo, Virginia, and Teresa Blasis.

Paris, Dondey-Dupré Père et Fils, Imp.-Lib. Éditeurs... 1824

First edition

GV1590 B3 1824

Essentially a history of Greek, Roman, early religious dance, and French court dance, the text is drawn from numerous writers including Mme. Elise Voiart, Joseph Juste Scaliger, Claude Francois Menestrier, Lous de Dahusac, Denis Diderot, and Jean-Georges Noverre. A large part of this book takes the form of conversations with "Sophie" and, occasionally, two more participants named Heraclite and Democrite. Baron writes about the dances of the period of Catherine de Medici and after. Baron is indebted to De Cahusac’s work La Danse Ancienne et Moderne (1754), a fact admitted by the author toward the end of the book. His work, however, is full of additional notes and anecdotes. It also has a folded plate of Feuillet notation. The work went into several later editions under the title Lettres à Sophie sur la danse…

À Paris, Chez les marchands de nouveautés, et chez tous les librairies des théâtres, 1830

First edition

GV1595 A4 1830

P. E. Alerme based this writing on letters to students and friends. Alerme considered dance an integral part of physical education. This text was written for the middle class, an attempt to democratize dance but also to ensure, through proper education that the art of dance would remain on an elevated artistic and social level. Alerme was with the Royal Academy of Music in Paris, and passed along details about the conventions of theatrical dancing that he believed should be reflected in the manners of social dancing – in formal ballroom settings and at more intimate functions. The author proposed the use of a mechanical corset, for either sex, to help prevent “falling” into sin while dancing the night away. Alerme’s serious if not somewhat naïve treatise presages several qualities found in the opportunistic characters of late nineteenth French novels by writers such as Guy de Maupassant, Gustave Flaubert, and Emile Zola. Alerme’s work was referenced often in later nineteenth-century dance literature. University of Utah copy in original blue wrappers.

London: Printed for Edward Bull, Holles Street, 1831

Second edition

GV1590 B57 1831

Paris, Chez Paulin, Libraire-Editeur, Place de la Bourse. 1832

ML3460 B63 1832

This work provides an excellent record of the ballets and dances popular during the First Republic, including a description of the Festival of the Supreme Being. The Festival, introduced by Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794), was his attempt to create a civil religion intended to unify post-revolutionary France. The highly-structured, ceremonial, and symbolic program for the festival was created by the painter David. Castil-Blaze also detailed the debut and early success of prima ballerina Marie Taglioni. Castil-Blaze is the pen name of Francois-Henry Joseph Blaze, a French music critic who compiled a dictionary on modern music. University of Utah copy bound with Chapelle-musique des rois de France. Paris: Paulin, 1832. Chapelle treats patented church music from early France and the instruments used.