Radical!

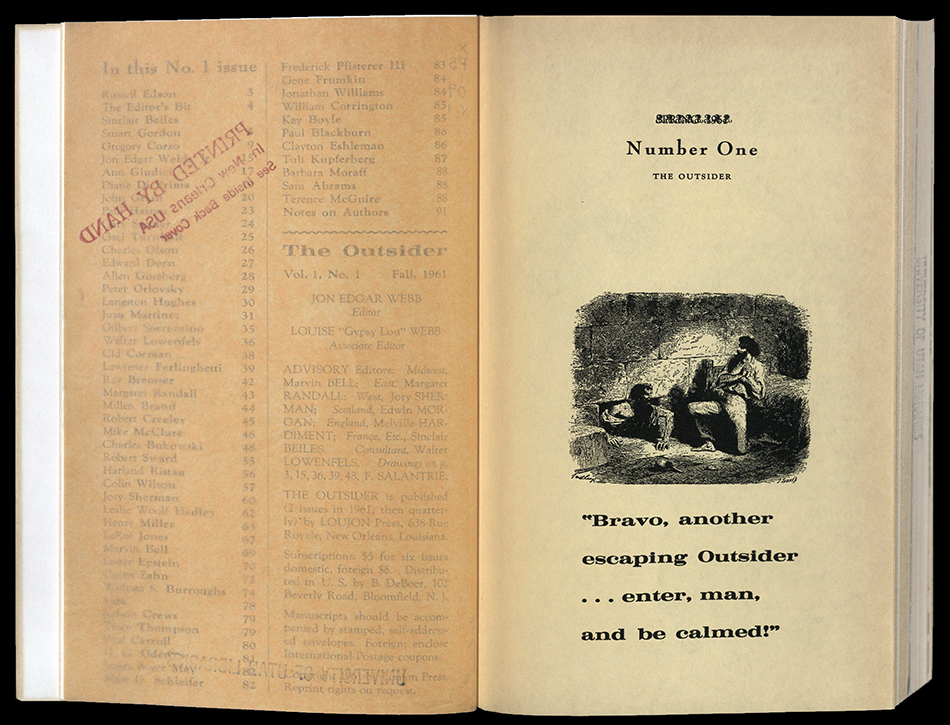

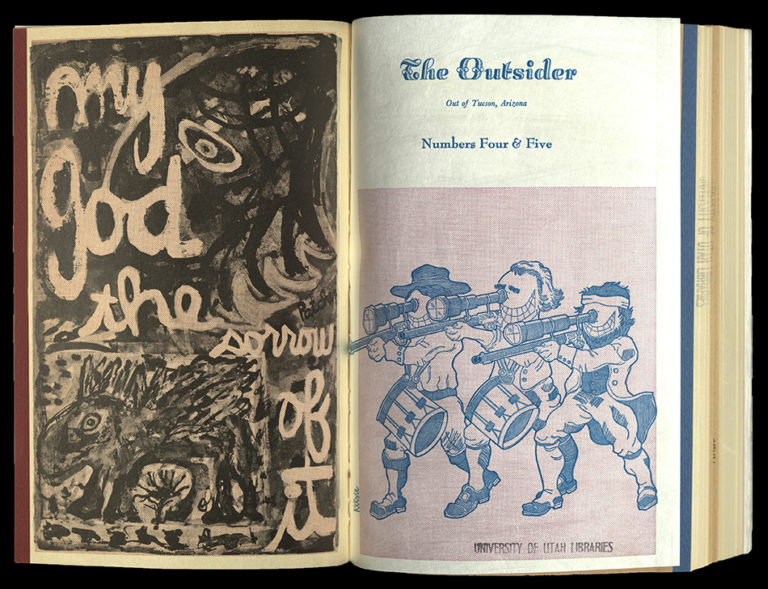

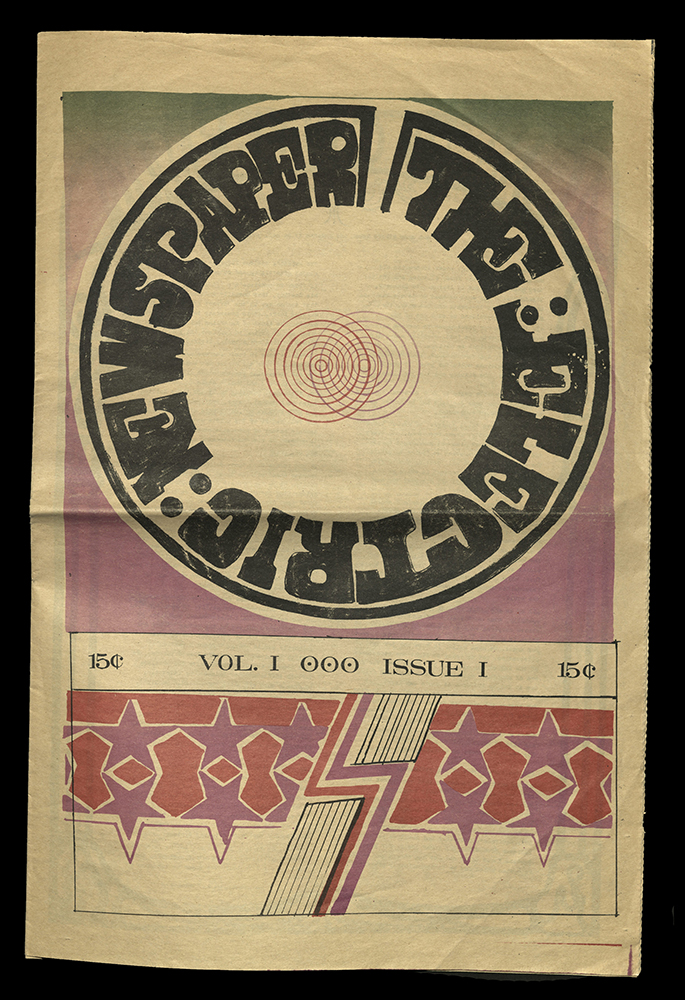

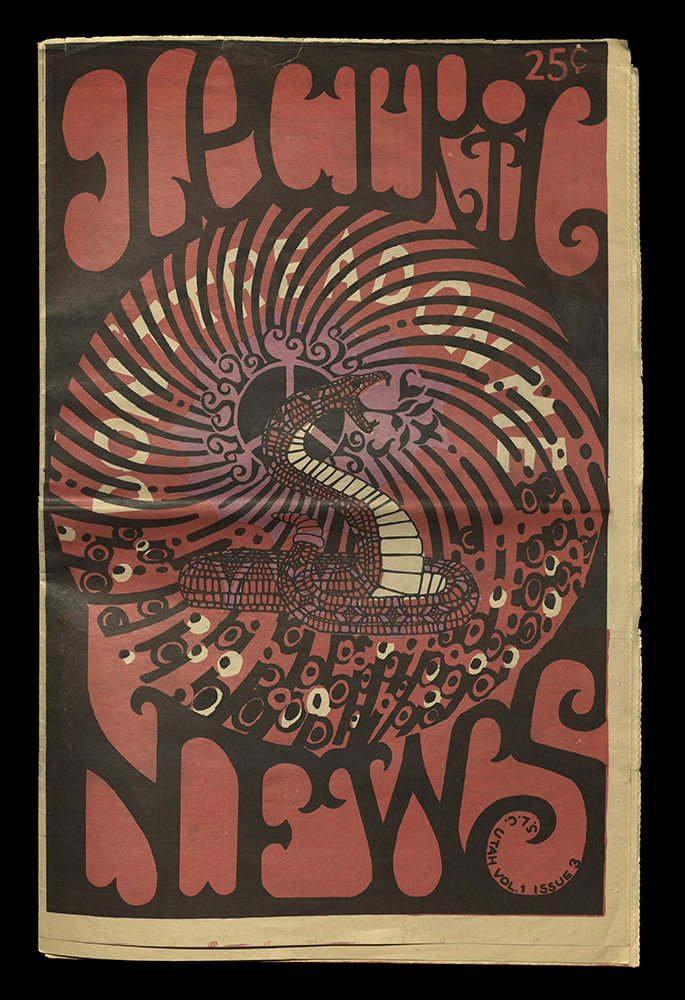

A RETROSPECTIVE OF TWENTIETH CENTURY DISSENT

Checklist for Radical!

Virtual Lecture for Radical!

Curated by Lyuba Basin, 2020

Digital exhibition produced by Lyuba Basin, 2020

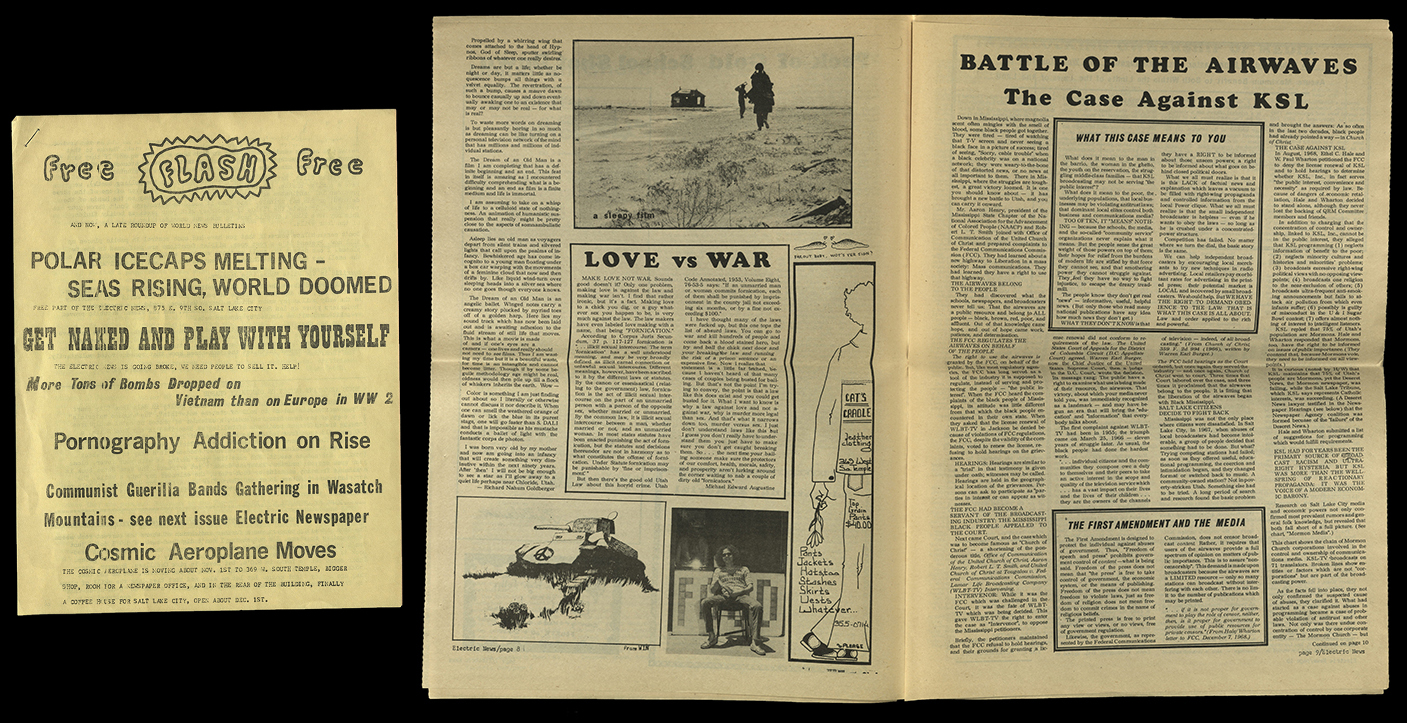

The literature of politics is multifaceted, filled with various genres that range from poetry to pamphlets, novels to newscasts. Today, new methods of disseminating literature allow voices from all walks of life to be heard on major digital platforms. However, a century ago, these virtual megaphones were nonexistent, and if you wanted a voice, you had to make it from scratch. During the early part of the 20th century, many writers, activists, and artists had become closely linked to the Labor and Socialist movements that were growing inside the United States. Over the course of several decades, such social movements emerged in different areas around the country, and particularly through the work of independent, underground or alternative presses which published radical ideas in the form of pamphlets, posters and literary magazines. Although unassuming in form, these materials created a cultural impact and developed intricate networks which continue to highlight issues of civil rights, censorship, and free speech today.

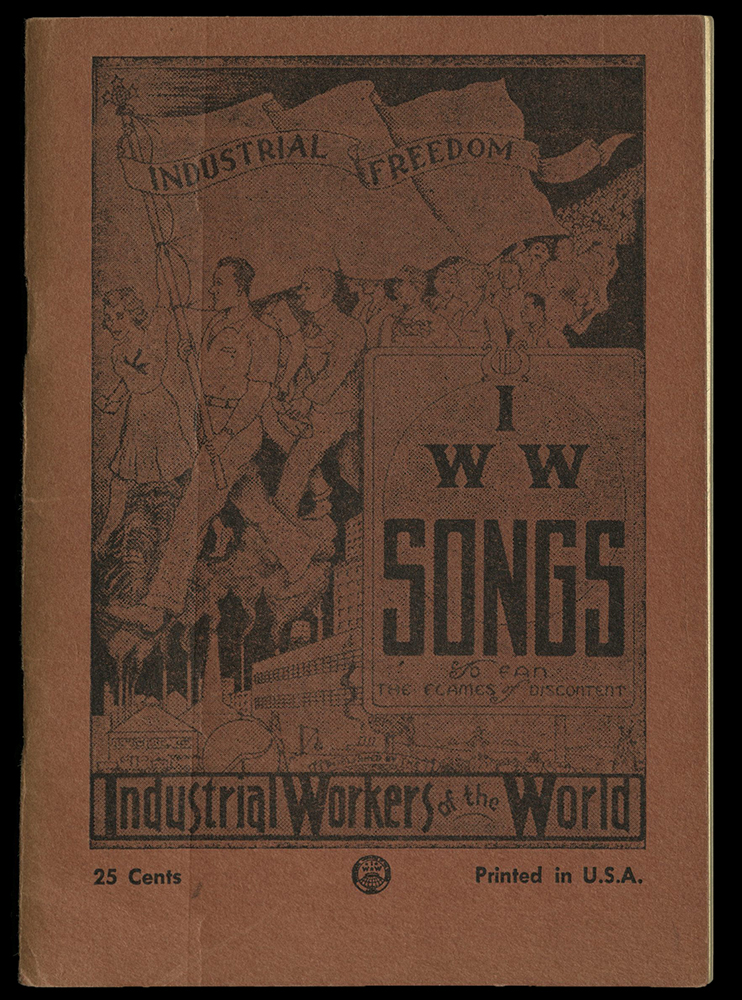

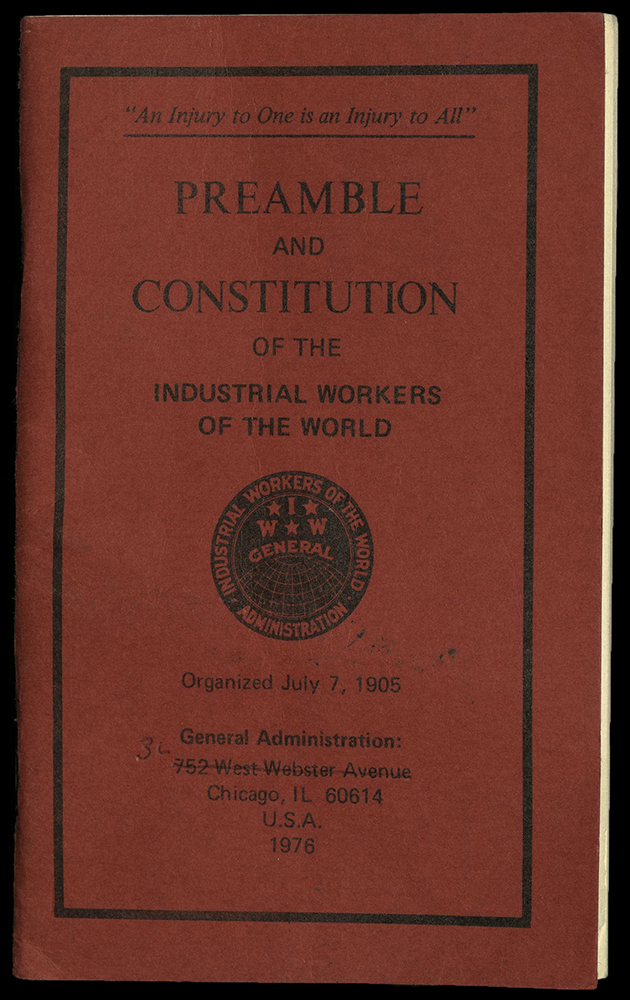

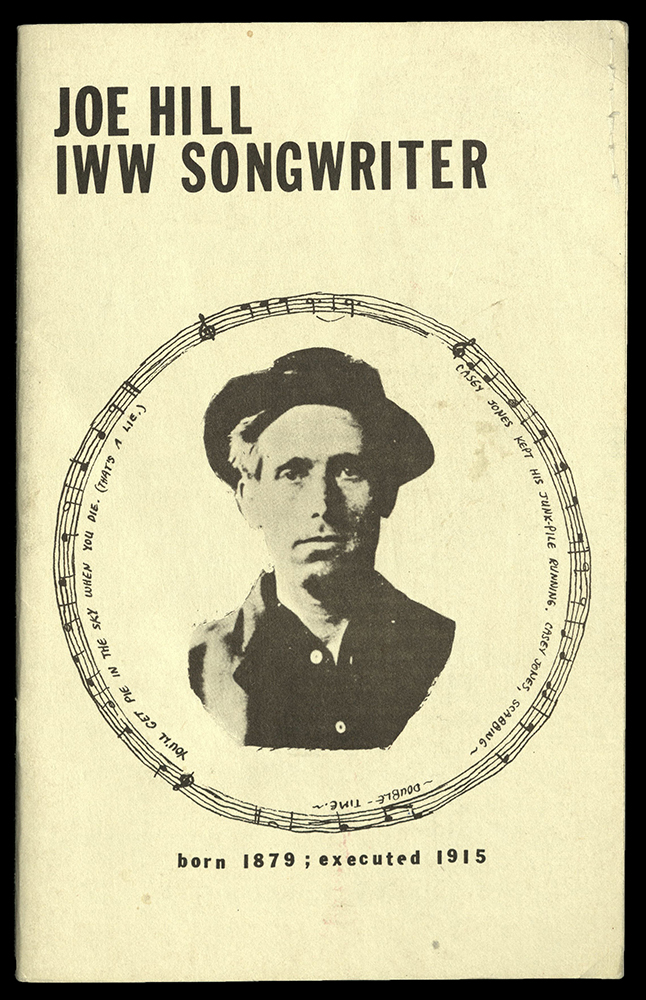

THE INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD

The Industrial Revolution, a period spanning the course of nearly one hundred years, saw the rise of machines, the middle class, and the urban population. From it, increased opportunities for employment could be found in factories, mills, and mines. The development of such jobs required an evolving organization of laborers, beyond what previous trade unions could offer - a union that could represent skilled and unskilled workers, workers from all trades and backgrounds, and workers from all over the world.

On June 24, 1905, a convention of some two hundred socialists, anarchists, members of the Socialist Party of America and Socialist Labor Party, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States, came together to form the Industrial Workers of the World.

The Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), often called the “Wobblies,” promoted “One Big Union” - a concept that cut across traditional guild and union lines to unite and organize workers as one social class against a capitalist industry. The notion of industrial unionism, as opposed to craft unionism, also pushed other aspects of social justice, such as being the first American union to welcome women, Black Americans, and immigrants not only into the organization, but into prominent roles of leadership.

Its inclusion of diverse workers, trades, and industries helped the I.W.W. grow in popularity. At its peak in 1917, it celebrated more than 150,000 members with active charters all throughout the United States, Canada, and Australia. By the 1920s, however, several factors caused membership to decline dramatically. Other labor groups saw the Wobblies as too radical. This same sentiment was also echoed by the government, which began to crack down on a growing number of socialist groups during the First Red Scare, after World War I.

Throughout the twentieth century, the Industrial Workers of the World were met with unparalleled resistance from Federal, State and Local governments in America. Beyond mere suppression of the First Amendment, many of its members and affiliates were imprisoned on the basis of legislative acts passed by Congress - such as the Espionage Act, the Sedition Act, the Smith Act, and the McCarran Act.

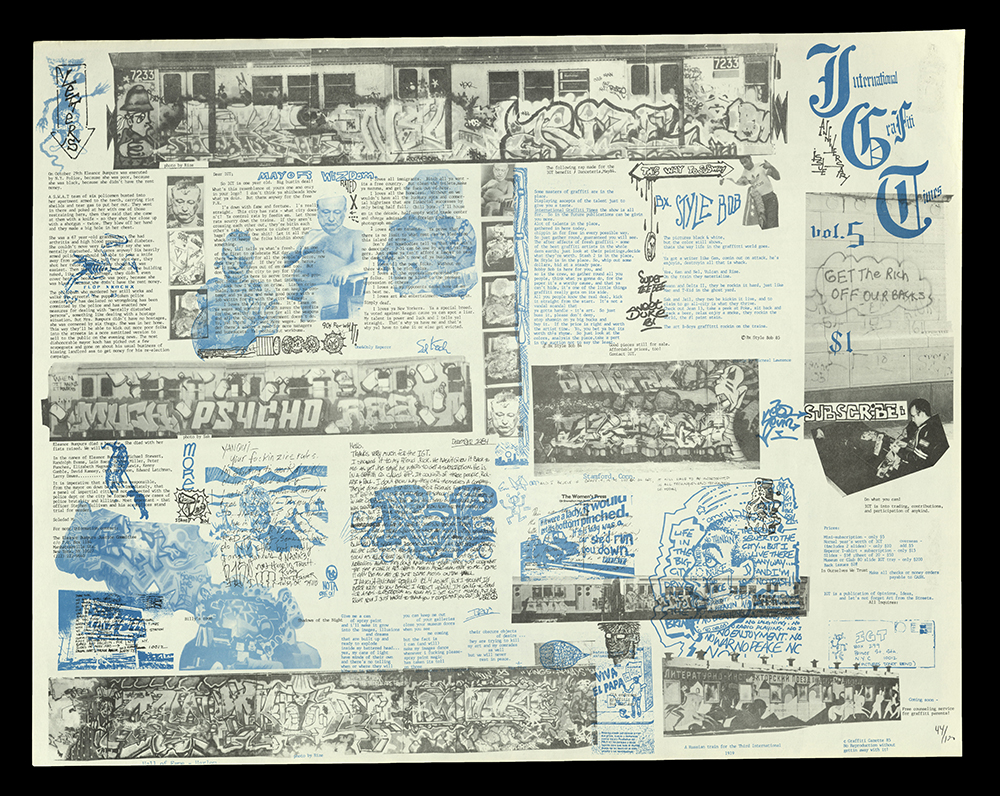

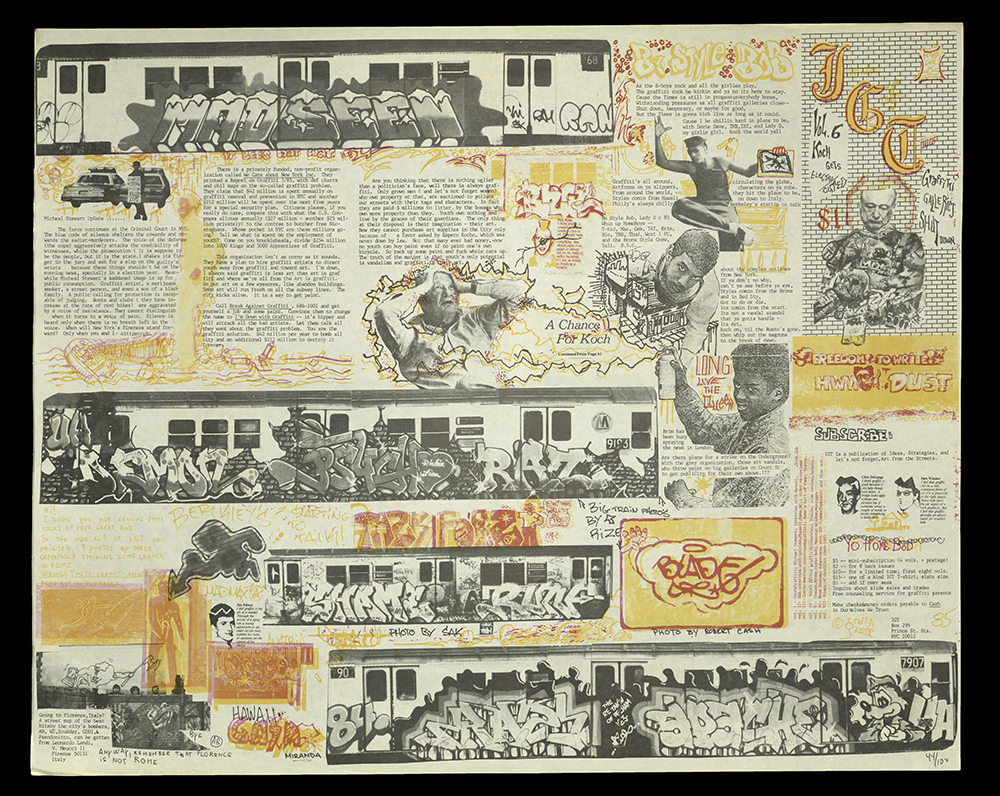

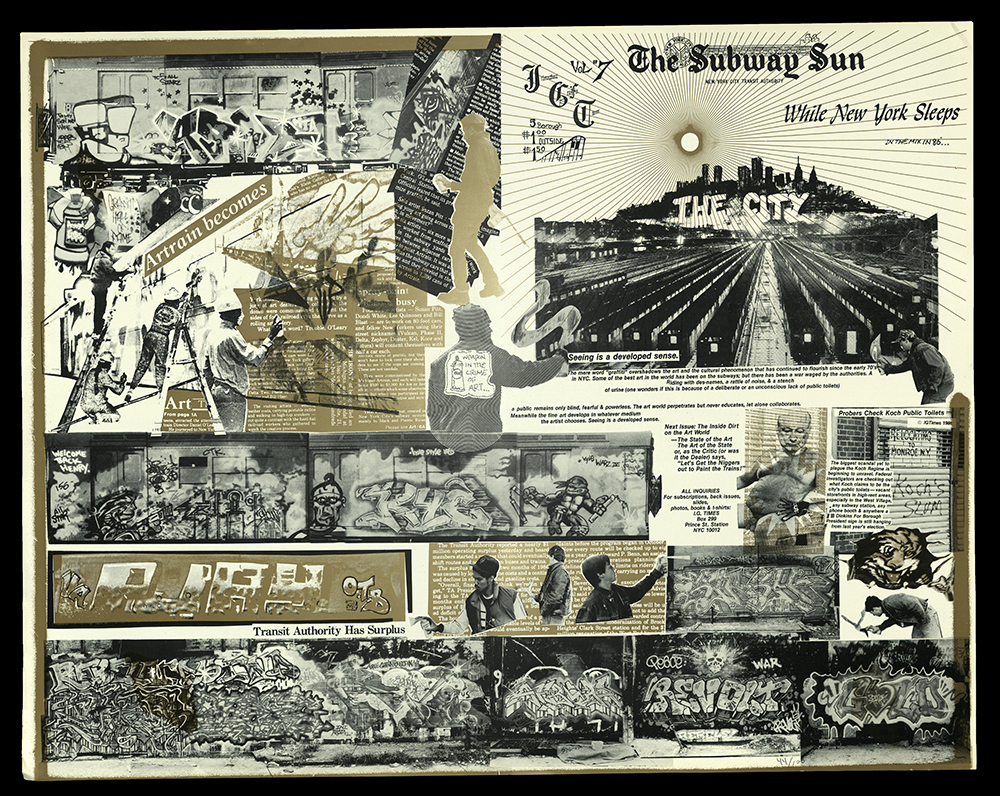

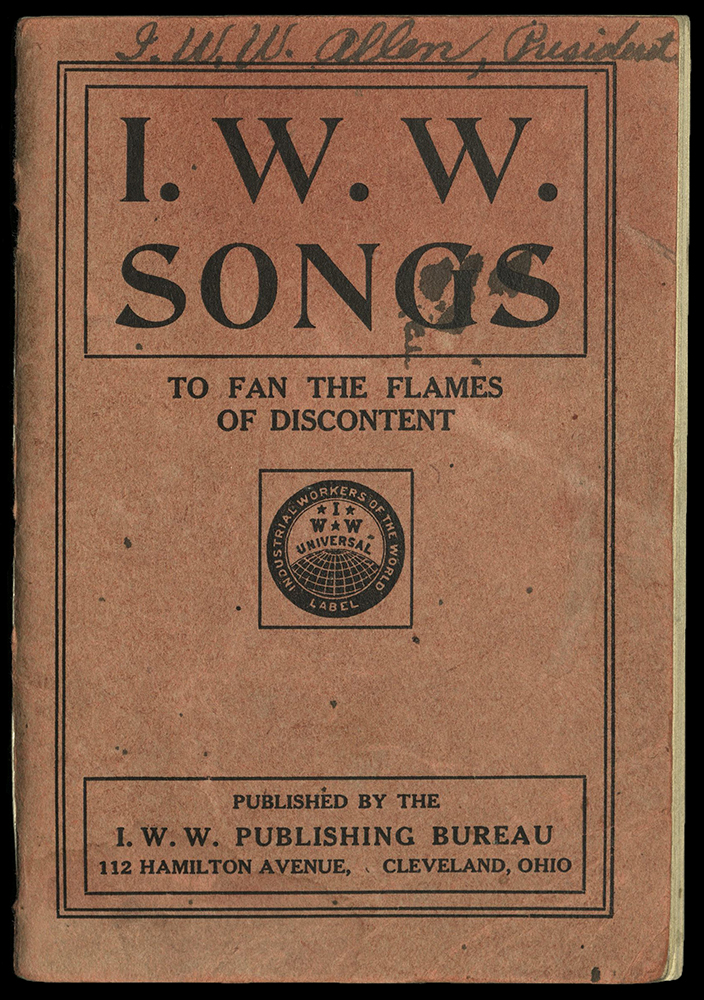

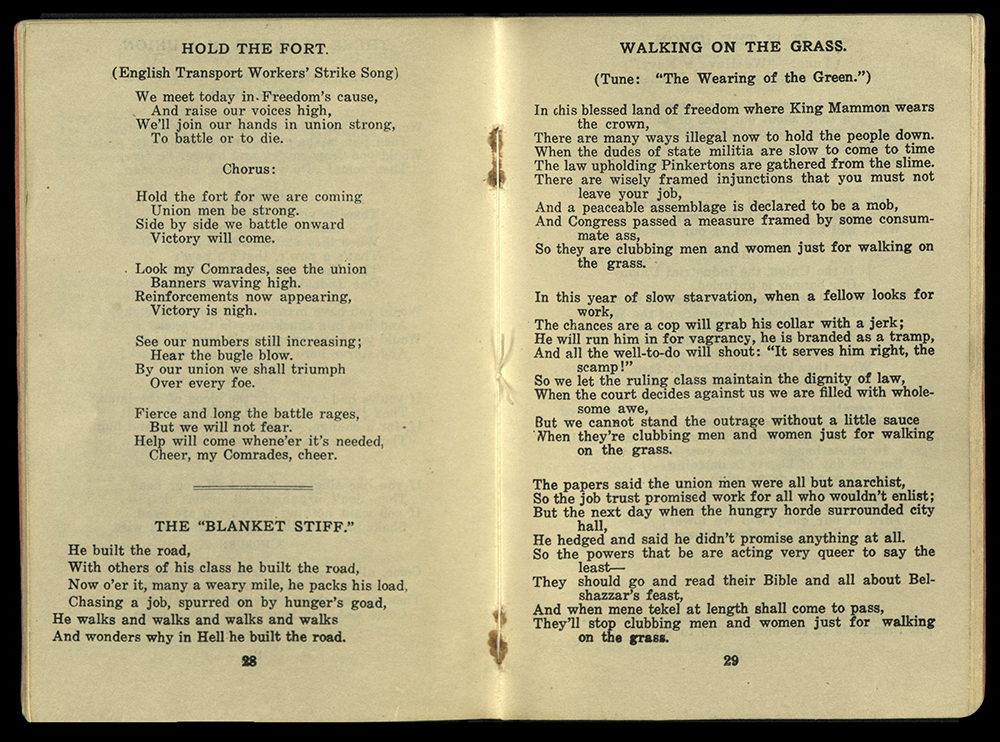

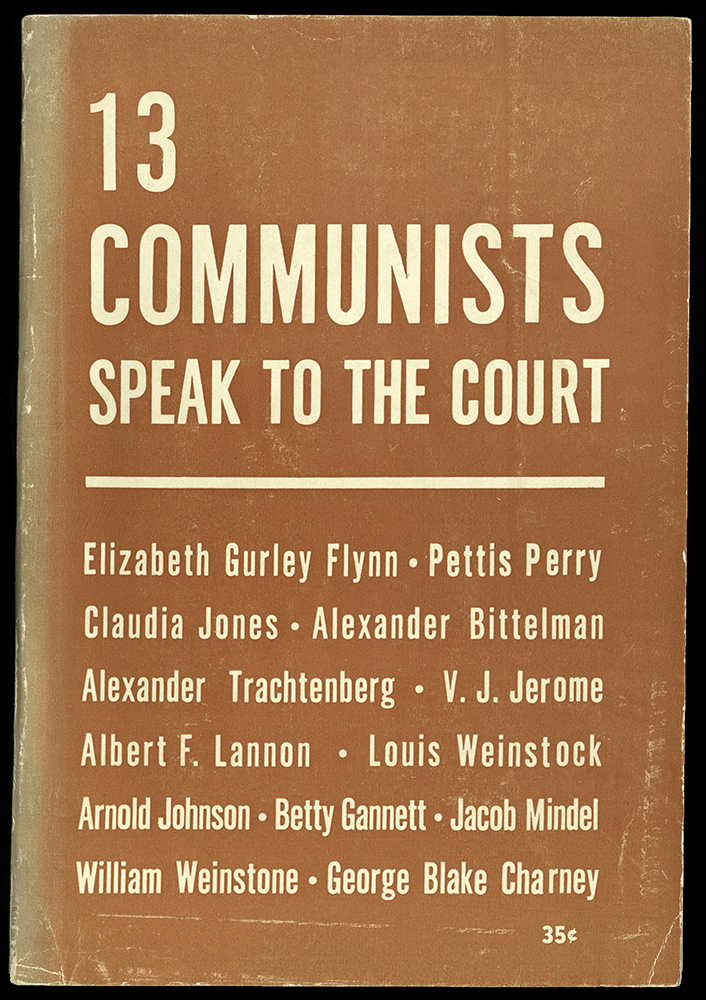

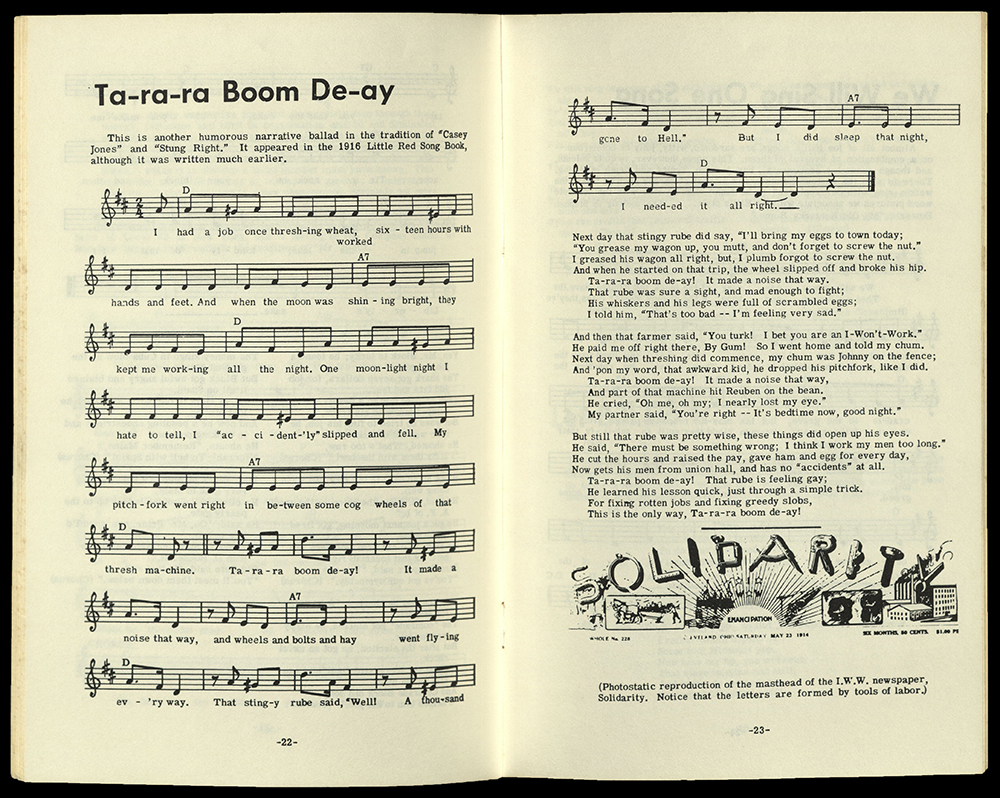

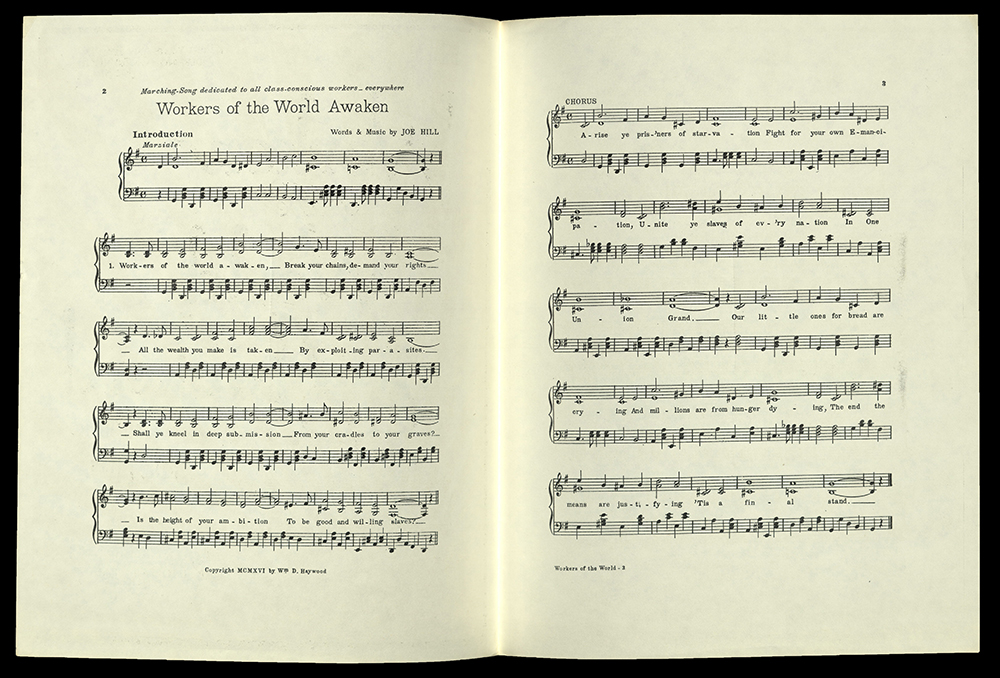

SONGS OF THE WORKERS; ON THE ROAD, IN THE JUNGLES, AND IN THE SHOPS

Industrial Workers of the World

I.W.W. Publishing Bureau : Cleveland, OH 1914

Joe Hill Edition (8th)

M1977 L3 I5 1914

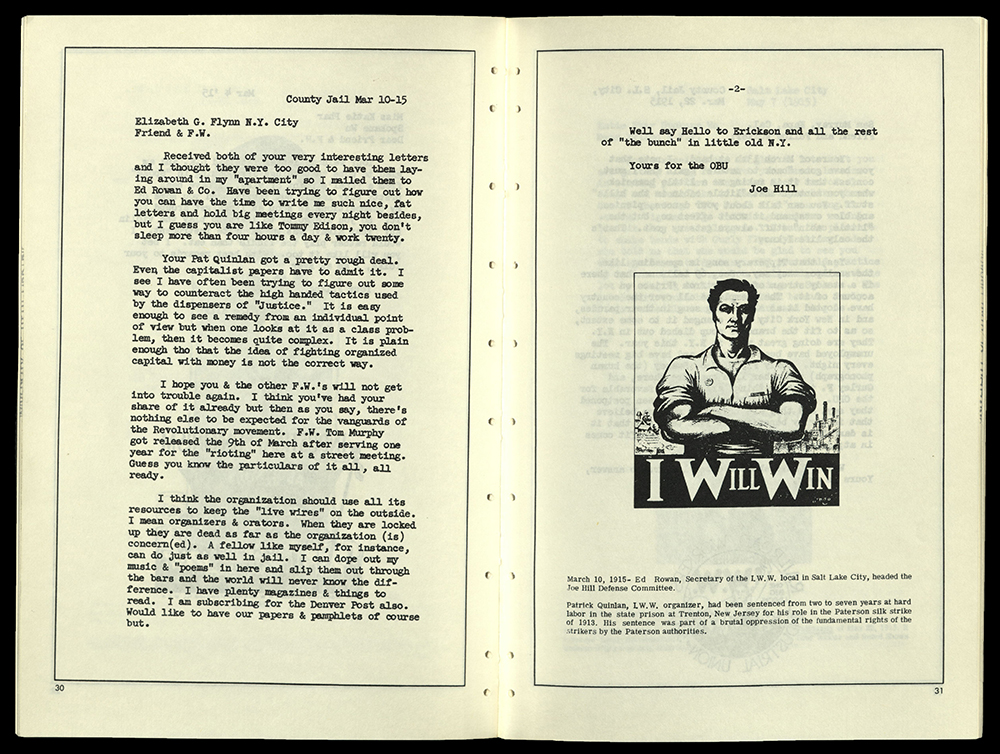

Since the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, songs have played an important role in spreading the message of the “One Big Union.” Such songs have been preserved in editions of the Little Red Songbook, or Songs of The Industrial Workers of the World. This compilation of tunes, hymns and songs were meant to help build morale and promote solidarity among the I.W.W. members. Between 1909 and 1995, thirty-six different editions were published. The eighth edition, published in 1914, commemorates I.W.W. songwriter, Joe Hill, who was arrested the same year for an alleged murder.

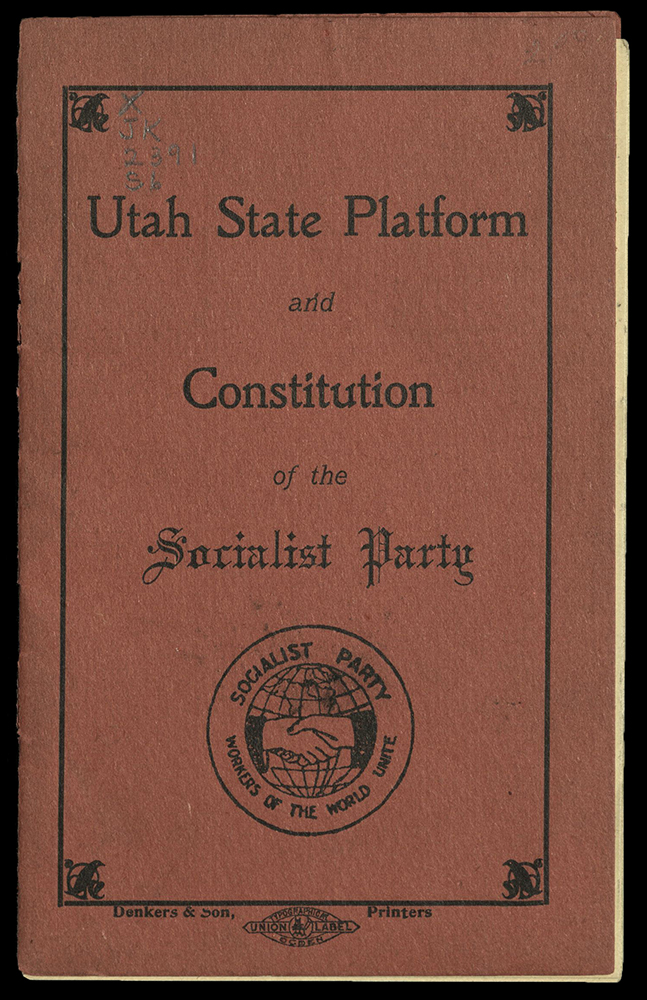

UTAH STATE PLATFORM AND CONSTITUTION OF THE SOCIALIST PARTY

Socialist Party (Utah)

Ogden, UT : Issued by the State Committee of the Socialist Party, 1908?

JK2391 S6

The Socialist Party in Utah began developing during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, with a particularly strong faction in the mining town of Eureka. Like Eureka, other mining areas in the state gave their support to the growing socialist party, with one of every eight members working in the mining industry. Utah was one of only eighteen states to have socialist representation in its legislature, with a diverse membership that included educators, clergy, white-collar workers, small-business owners, and farmers. Between 1900 and 1923, approximately one hundred socialists were elected to a variety of offices throughout the state.

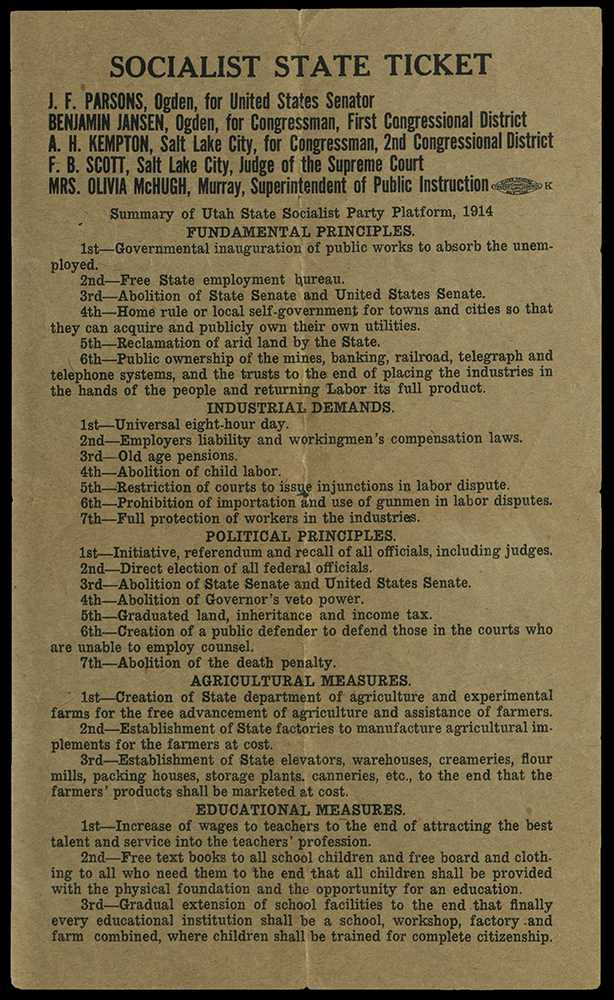

SOCIALIST STATE TICKET

Socialist Party (Utah)

Salt Lake City, UT : 1914

JK2391 S6 S63 1914

The socialist party in Utah was unique because it grew out the tradition of Christianity. Members of the Church of Latter-Day Saints comprised approximately forty percent of the Utah Socialist party membership and, as part of a larger, nationwide movement, many American Protestant churches advocated socialism and were strong supporters of the miners laboring in the Mountain West region. Christian socialists preached a message that combined Marxism with lessons from the Christian Gospels, promoting cooperation, community, and equality in regards to power and wealth.

Despite the influence of Christianity on socialism in Utah, there was plenty of debate over the issue, with many non-religious socialists arguing that there was no place in the movement for Christian rhetoric or values. Secular socialists believed that churches were aligned with the status quo, and their true allegiance was to employers and capitalists, rather than the working class.

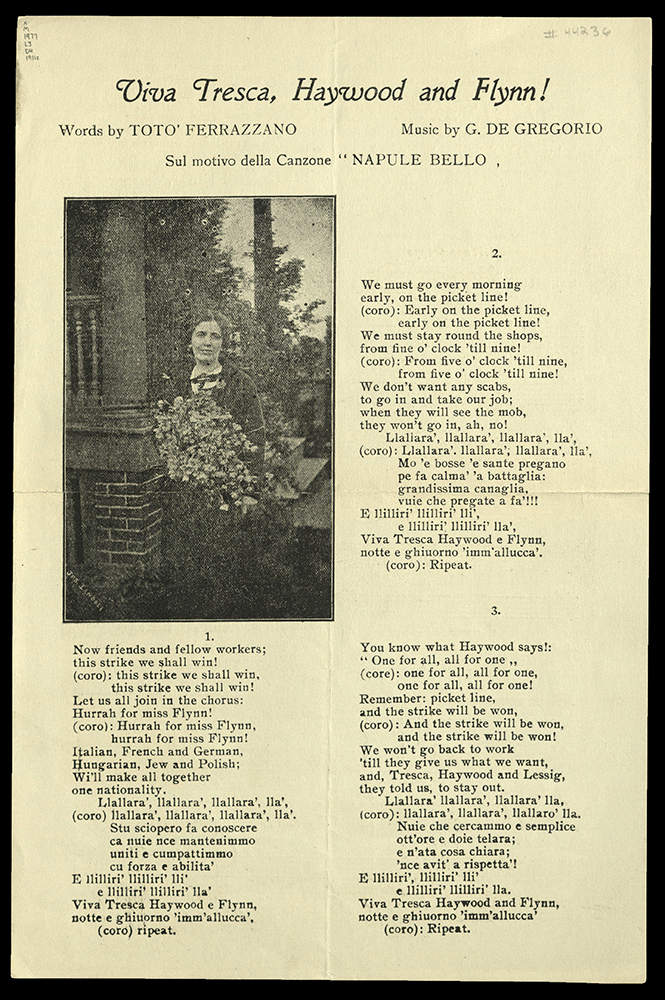

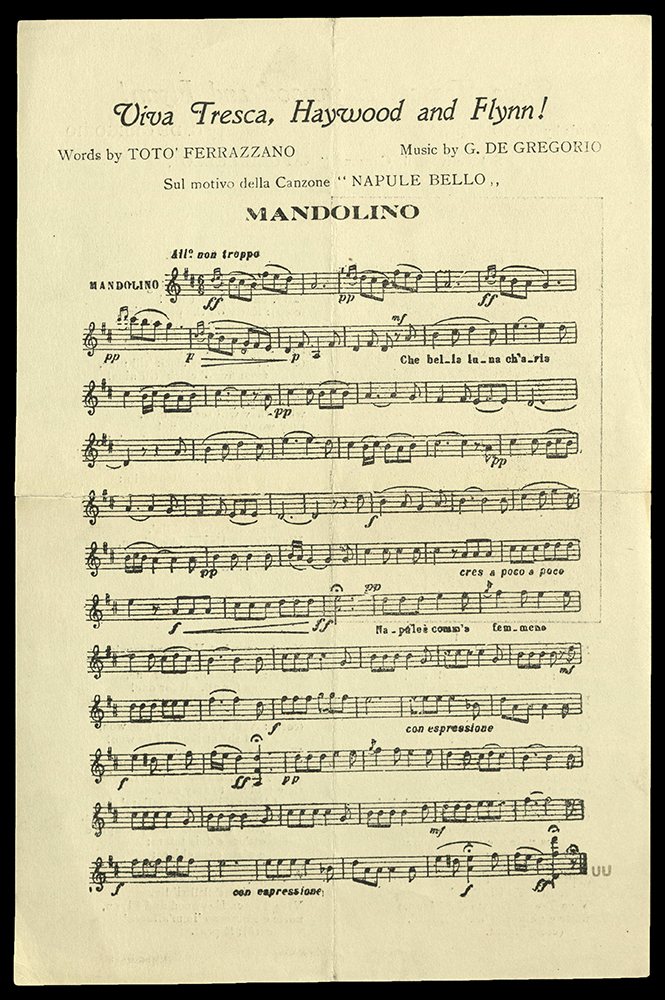

VIVA TRESCA, HAYWOOD, AND FLYNN

G. De Gregorio

[Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified], [between 1910 and 1919?]

M1977 L3 D4 1910z

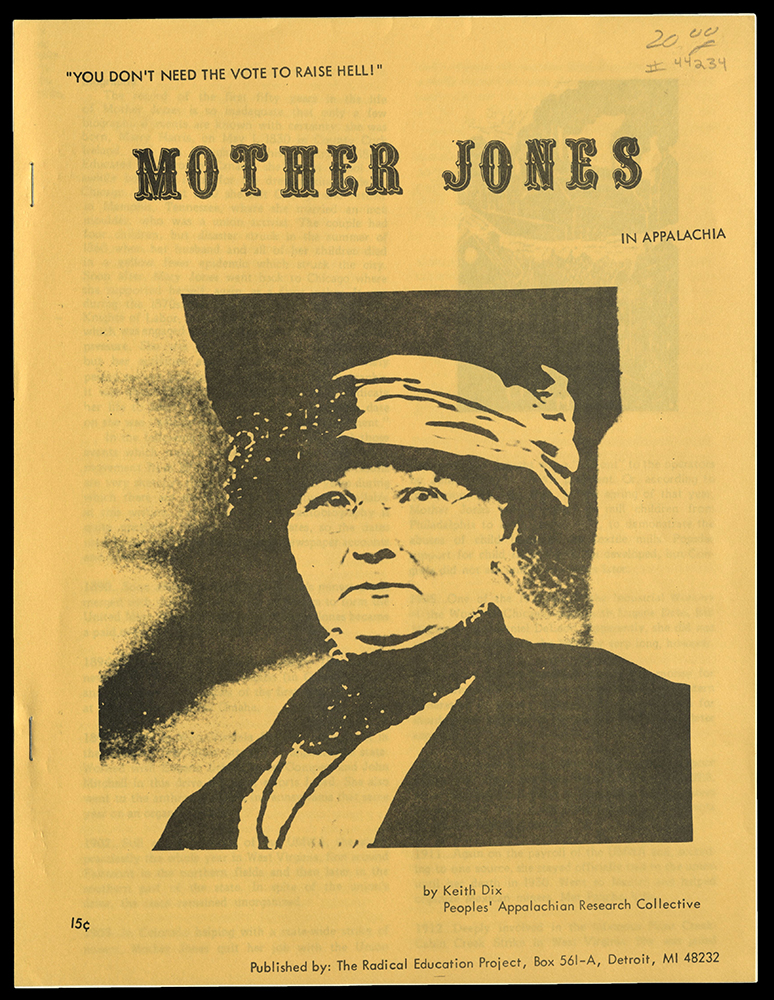

Carlo Tresca, William "Big Bill" Haywood, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn were prominent members of the Industrial Workers of the World, an international labor union started in the early twentieth century. Commonly referred to as Wobblies, the I.W.W.s promote the concept of “one big union,” contending that all workers should be united as a social class to replace capitalism and wage labor with industrial democracy.

On June 24 1905, a group of 200 socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists came together for the first ever International Congress, or the Industrial Union Convention. Here, the Industrial Workers of the World was founded. The I.W.W. founders included William D. (Big Bill) Haywood, James Connolly, Daniel de Leon, Eugene Debs, Thomas Hagerty, Lucy Parsons, Mary Harris (Mother) Jones, Frank Bohn, William Trautmann, Vincent Saint John, Ralph Chaplin, and many others. From then on, the I.W.W. cut across traditional guild and union lines to organize workers in a variety of trades and industries, promoting the idea of “industrial unionism” as opposed to “craft unionism.”

Song book celebrating Tresca, Haywood and Flynn. Composed by G. De Gregorio, with lyrics by Toto Ferrazzano. Songs in English and Italian.

HILLACRE PRESS

In 1903 Frederick Conrad Bursch became the editor of what was known as the Literary Collector Press. In addition to the fulfillment of monthly subscriptions, Bursch began the publication of imprints that he called “the second class.” Mostly they were reprints of standard literary texts, or represented special bibliographic material, dressed up in attractive formats and clean-cut, crisp typography; on good paper (with handmade paper, or Japanese, employed frequently); and turned out in small, limited editions.

The life of the Literary Collector was cut short, perhaps due to financial troubles or lack of commercial competence. It would take at least four years for Bursch to get back on his feet, likely with the help of his father, and start a new press that was developed more specifically for limited edition runs and imprints of his choosing. After moving to a small one-acre property on a hill in Riverside, The Hillacre Bookhouse was born. Print runs ranged from about 100 to 500 copies. Although information about the Hillacre Bookhouse is scarce, what remains are a few known titles from authors such as Olive Schriener, Frank R. Stockon, Edwin L. Godkin, Leon Pierce Clark, Arturo Gionvanniti and Lincoln Steffens.

Steffens became a close friend and companion of Bursch, and the two often enjoyed long walks and sailing trips. After publishing some of Steffens’ work, Steffens introduced Bursch to other poets, including fellow-Harvard alum John Reed — American journalist, poet, and socialist activist, best remembered for his first-hand account of the Bolshevik Revolution, Ten Days That Shook the World. Reed’s poetry at this time was flourishing and, unlike his later work, was not radical in tone or content. The Hillacre Bookhouse went on to publish five items by Reed: two broadsides and three books of poetry. The relationship between Reed and Bursch extended beyond the business arrangements of author and publisher. They became good friends and carried on a correspondence through 1919, only a year before Reed’s death in the newly formed Soviet Union.

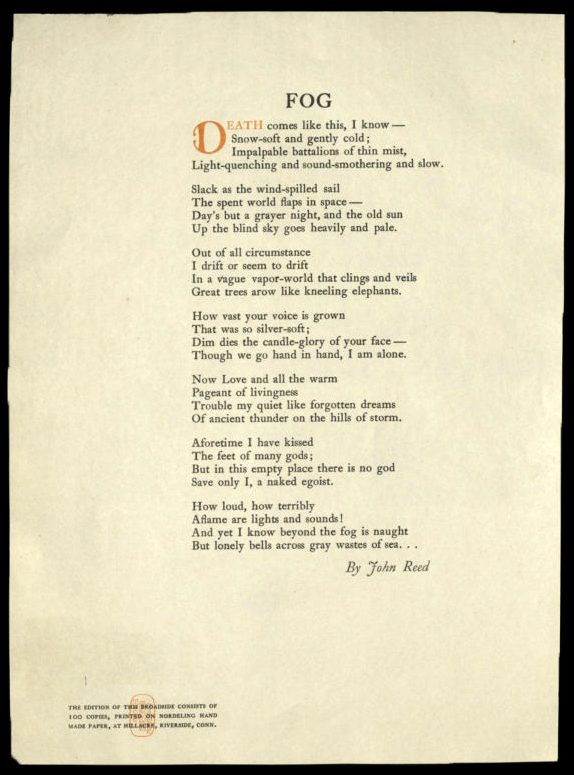

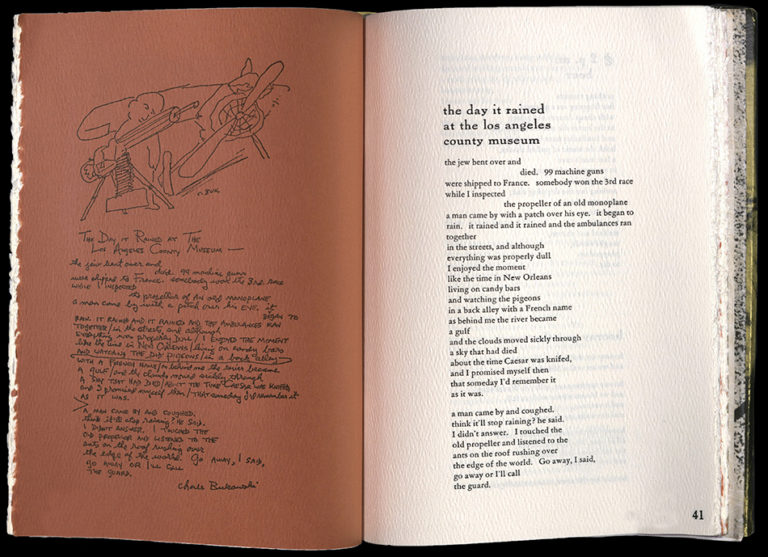

FOG

John Reed (1887 – 1920)

Riverside, CT : Hillacre Bookhouse, 19 –

PS3535 E2786 F6

As a student at Harvard, John Reed attended local Socialist Club meetings, which inspired him to investigate the world outside the United States. After graduating in 1910, Reed set off to Europe, visiting England, France and Spain. Upon his return, he established a path to become a journalist and settled in Greenwich Village, New York. There, a hub of poets, writers, activists and artists was flourishing. He soon joined the staff of the Masses, a socialist publication edited by Max Eastman. Broadside. Printed on Nordeling handmade paper. Edition of 100 copies.

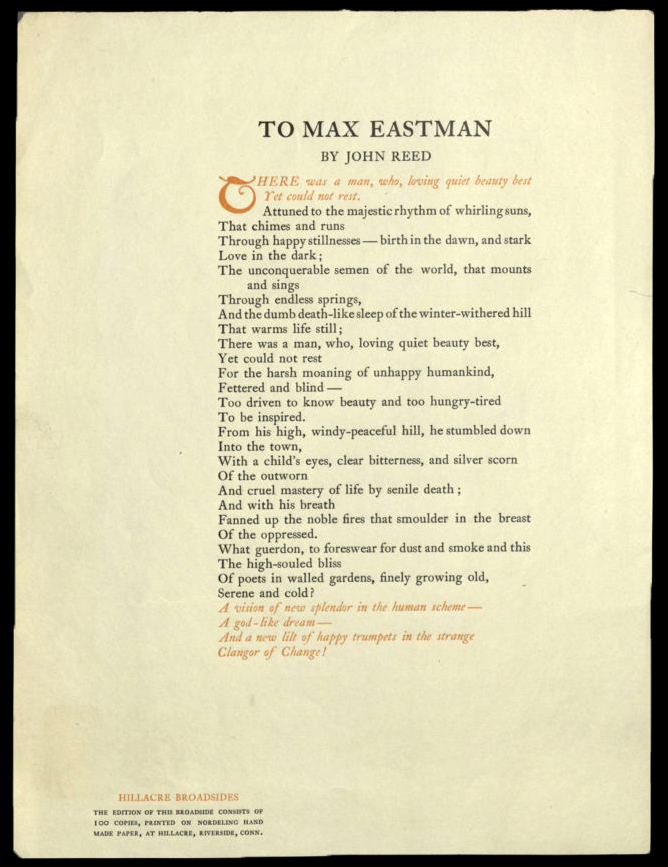

TO MAX EASTMAN

John Reed (1887 – 1920)

Riverside, CT : Hillacre Bookhouse, 19--

PS3535 E2786 T6

John Reed’s relationship with Max Eastman began in 1913, when Reed joined the staff of the Masses, a socialist publication edited by Eastman. Reed contributed review, essays and more than 50 articles, including those which would later be collected in Reed’s most famous work, Ten Days That Shook the World. Reed’s contribution to the Masses, along with his aggressive political activism, caught the eye of the United States government, who filed charges of sedition against him and Eastman under the provisions of both the Espionage and Sedition Acts.

Broadside. Printed on Nordeling handmade paper. Edition of 100 copies.

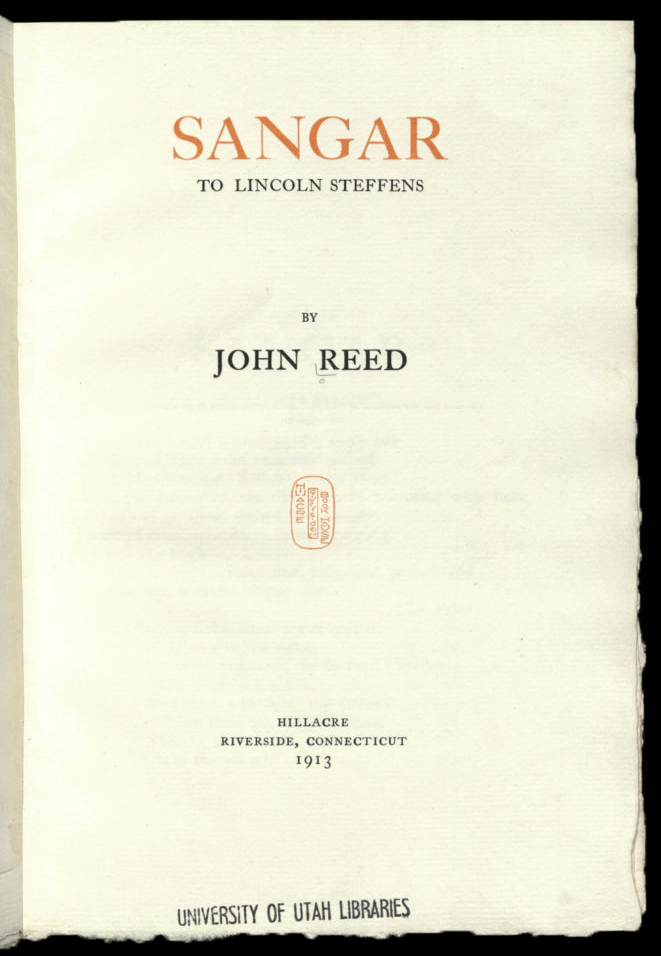

SANGAR : TO LINCOLN STEFFENS

John Reed (1887 – 1920)

Riverside, CT : Hillacre Bookhouse, 1913

PS3535 E2786 S2

While at Harvard, John Reed met Lincoln Steffens, a journalist who gained a reputation as a muckraker. Steffens helped a young Reed enter the world of journalism, providing him with an entry-level position on The American Magazine. Steffens later became an editor for McClure’s magazine, and is remembered for investigating political and corporate corruption.

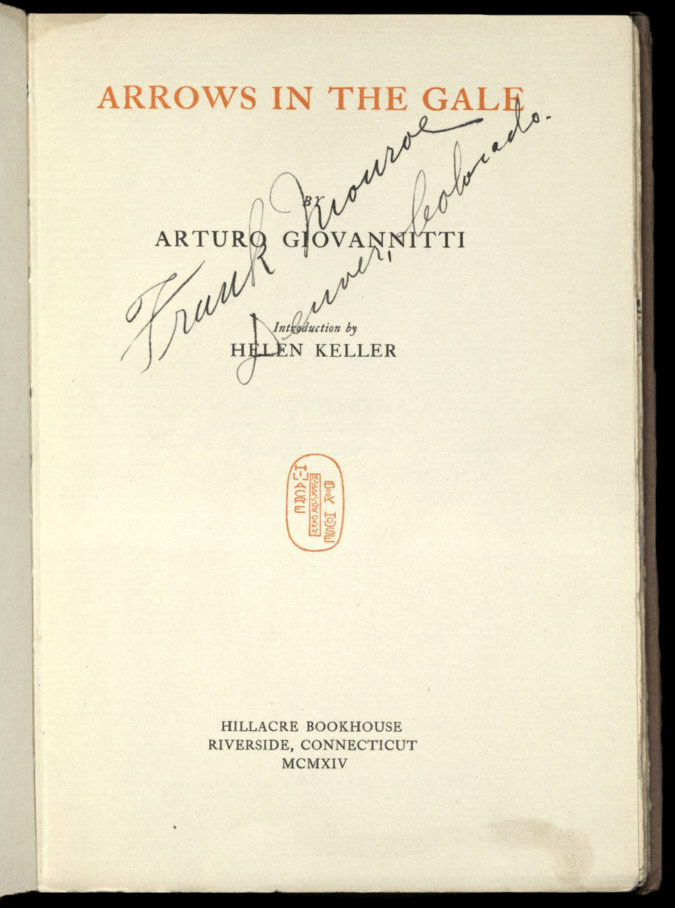

ARROWS IN THE GALE

Arturo Giovannitti (1884 – 1959)

Riverside, CT : Hillacre, 1914

PS3513 I78 A7

Arturo Giovannitti was an Italian-American union leader, socialist political activist, and poet. Giovannitti first immigrated to Canada in 1900, and soon after came to the United States. He first started working in coal mines and on railroad crews, and during this time was introduced to the Industrial Workers of the World. During the onset of the Lawrence textile strike in 1912, Giovannitti was asked by Joe Ettor, the I.W.W.’s top Italian-language leader, to help coordinate relief efforts. In the midst of a police crackdown on an unruly mob, striker Anna LoPizzo was shot and killed. Though miles from the scene, Giovannitti and Ettor were arrested and charged with inciting a riot leading to the loss of life.

While in prison, Giovannitti focused his energy on writing poems. Several of those poems were published in leading socialist journals. In the wake of the trial, Giovannitti published his first book of poems, Arrows in the Gale. In the introduction to the work, Helen Keller wrote, “Giovannitti is, like Shelley, a poet of revolt against the cruelty, the poverty, the ignorance which too many of us accept.” After Giovannitti was acquitted, he avoided any involvement in the volatile labor strikes and, instead, devoted himself fully to poetry.

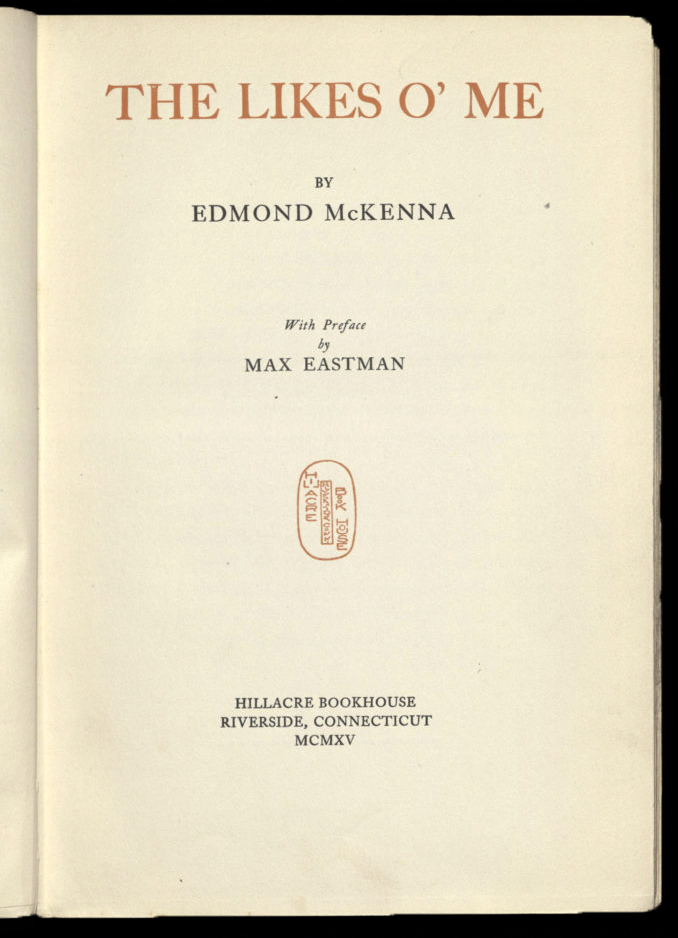

THE LIKES O' ME

Edmond McKenna

Riverside, CT : Hillacre, 1915

PS3525 A2556 L5

From Anthology of Magazine Verse for 1915: “The public will do well to pay considerable attention to this slim volume. Mr. McKenna is a militant warring against the wrongs of civilization, but with verse that is passionately charged with truth. He employs both formal metre and free rhythms. In the series of verses that make up the poem called “The Likes O’ Me,” there is an austere and solemn mysticism of a soul brooding upon its industrial captivity and the forces which batter it from within and without. It is an extraordinary testament of the millions of “Mes” in our industrial world commenting menacingly of the relation to the Master, the Church, the State, the Ladies, and War. There is more pity and sympathy in these verses than one would suppose from the free and outspoken expression of oppressive conditions. But as Mr. Eastman says, 'There is poetry and truth of the real world in this book,' which to neglect is to betray one’s faith in humanity and civilization.” Preface by Max Eastman.

TAMBURLAINE : AND OTHER VERSES

John Reed (1887 – 1920)

Riverside, CT : Hillacre Bookhouse, 1917

PS3535 E2786 T3

Tamburlaine is the last work of poetry of John Reed’s that was published by Frederick Bursch’s Hillacre Press. The titular poem, “Tamburlaine” refers to Timur (also known as Tamerlane), the renowned Turco-Mongol conqueror who founded the Timurid Empire and became the first rule of the Timurid dynasty during fourteenth century. Prior to Reed’s poem, other literary works were inspired by the great conqueror, including the plays Tamburlaine (1588) by Christopher Marlowe and Tamerlane (1701) by Nicholas Rowe, as well as Tamerlane: and Other Poems (1827), the first published work by Edgar Allen Poe. Edition of 500 copies.

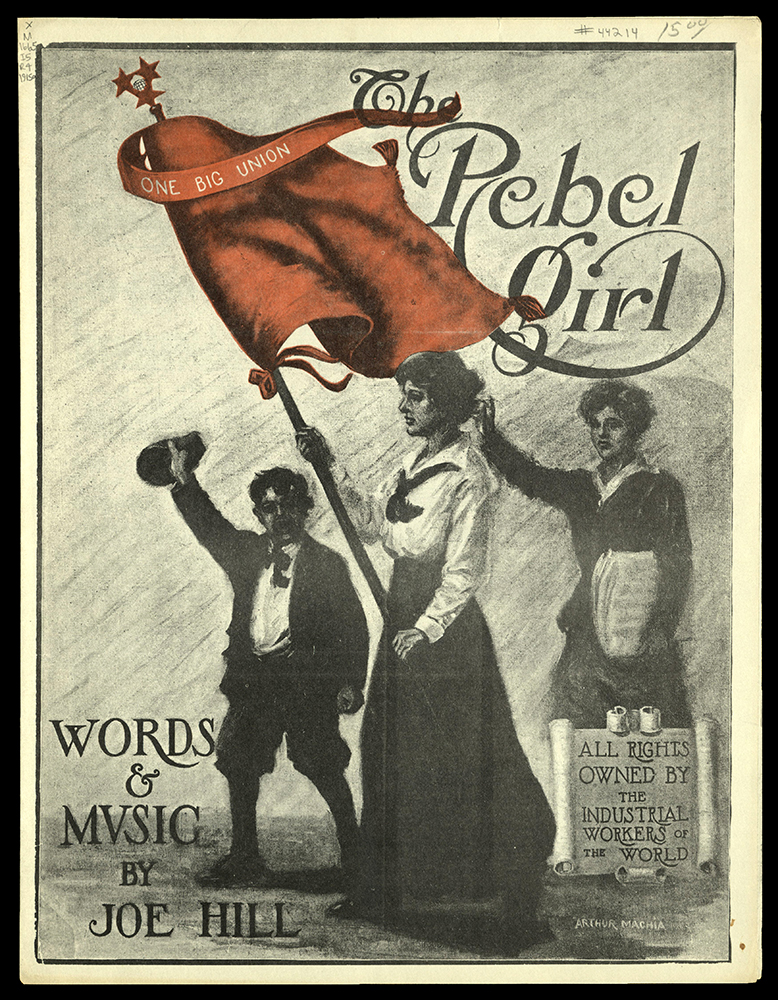

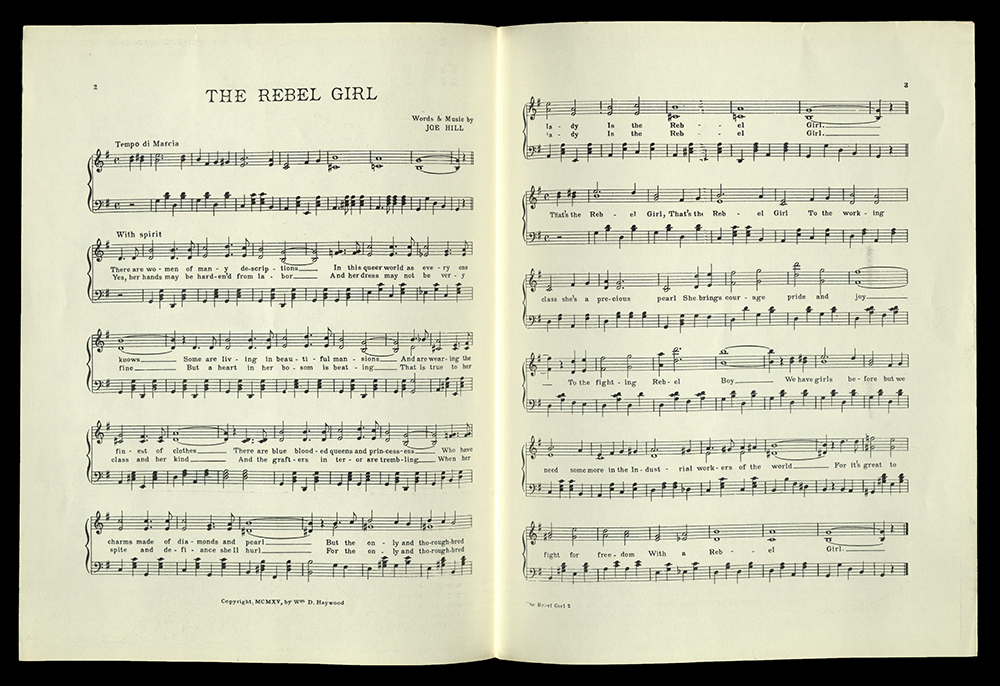

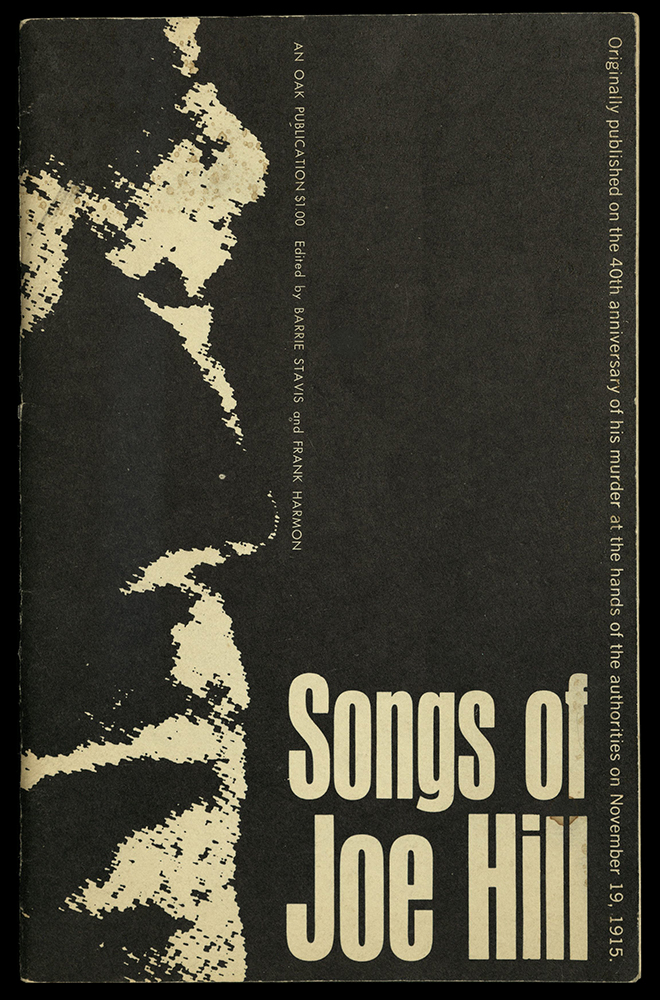

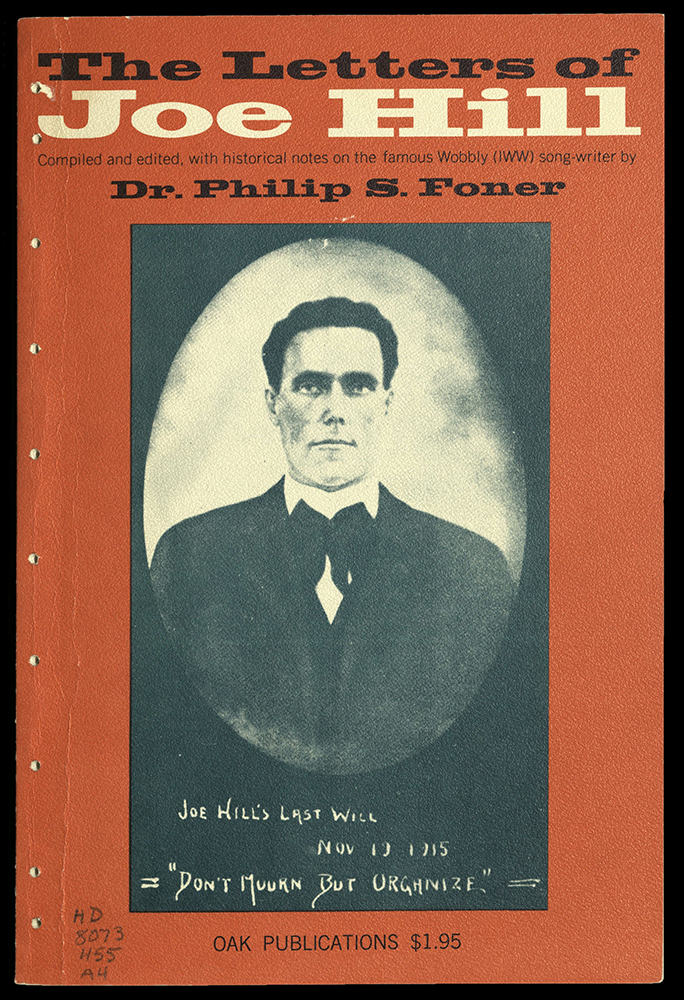

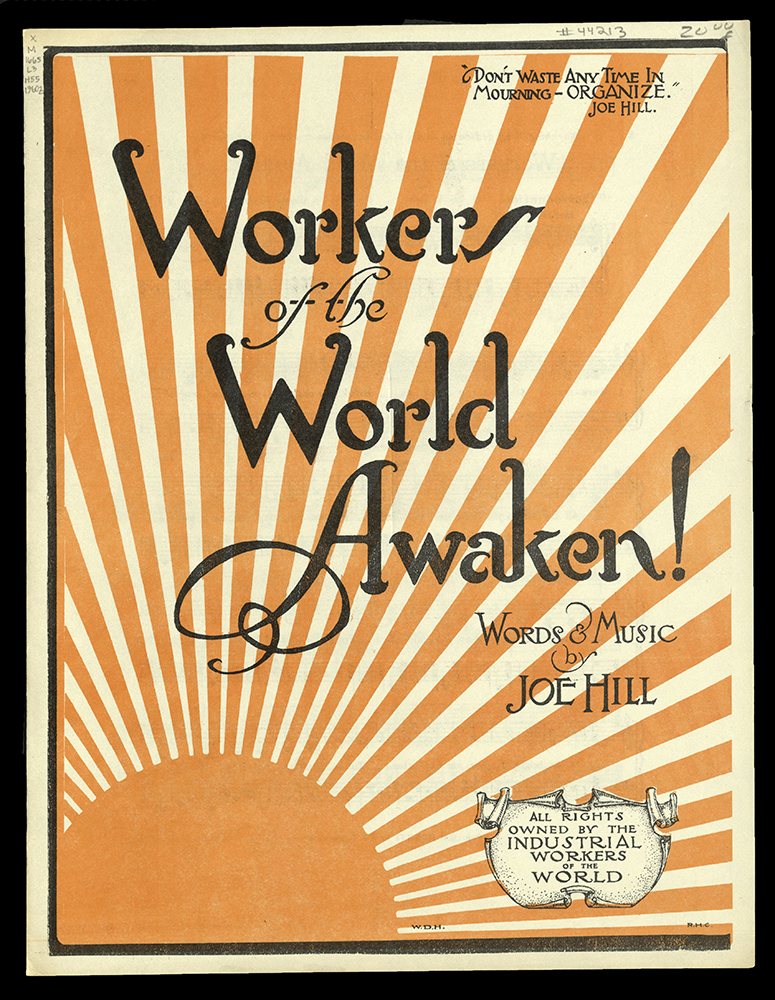

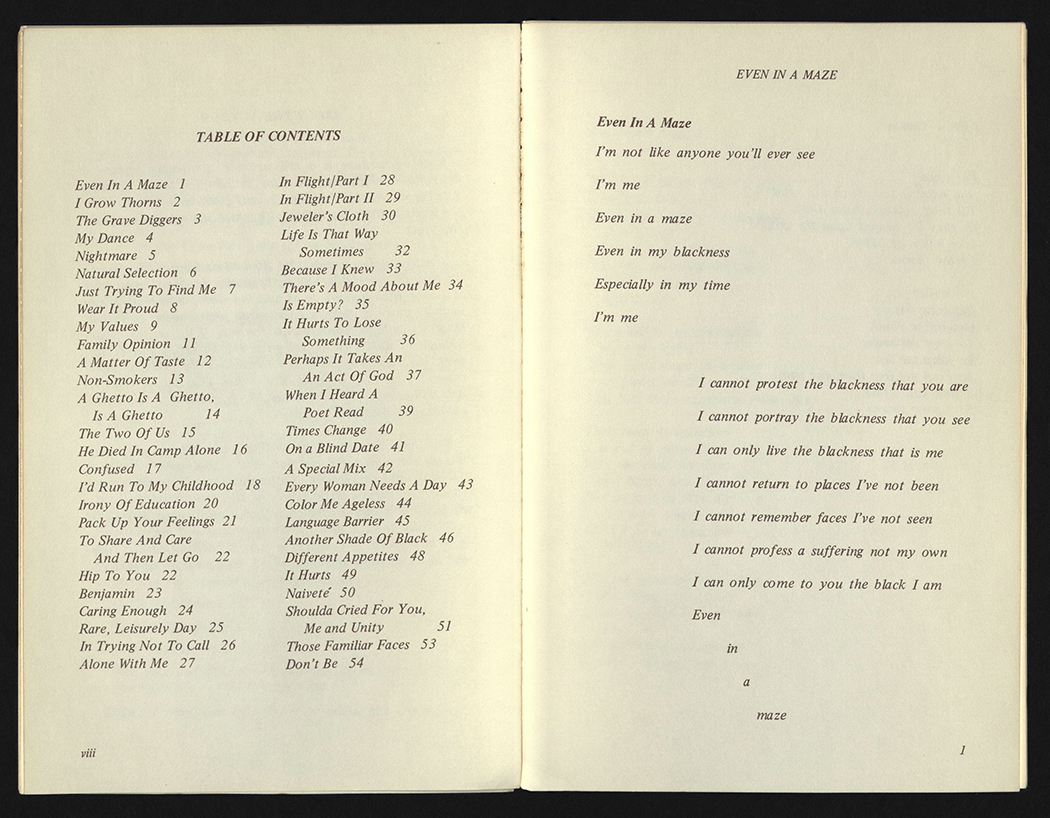

THE REBEL GIRL

Joe Hill (1879 – 1915)

Ithaca, NY : Glad Day Press, 1970s (reprint)

M1665 I5 R4 1915a

“The Rebel Girl” is a song written by Joel Emmanuel Hagglund (Joe Hill) that was published as sheet music by the Industrial Workers of the World in 1915, for their Little Red Songbook. It is said that the song was inspired by and written for I.W.W. activist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Hill was a Swedish-born labor activist, songwriter, and member of the I.W.W. Hill rose to prominence in the organization, traveling across the country while making speeches, and writing political songs and satirical poems. His songs were often parodies of Christian hymns written for the union members to sing along to. In 1914, while Hill was working at the Silver King Mine in Park City, Utah, he was convicted of the murder of John G. Morrison, and his son. Morrison was a former policeman and local grocer in Salt Lake City, and was well-known in the area. Following political debates and international calls for clemency, Hill was unable to appeal his case and was sentenced to execution by firing squad. On November 19, 1915 Joe Hill was executed at Utah’s Sugar House Prison. Hill’s final will, which was eventually set to music by Ethel Raim, reads:

My will is easy to decide

For there is nothing to divide

My kin don’t need to fuss and moan

“Moss does not cling to rolling stone”

My body? Oh, I could choose

I would to ashes it reduce

And let the merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers grow

Perhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life and bloom again

This is my Last and final Will

Good Luck to All of you

Joe Hill

THE ESPIONAGE ACT AND THE SEDITION ACT AMENDMENT

"There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt, to destroy our industries wherever they thought it effective for their vindictive purposes to strike at them, and to debase our politics to the uses of foreign intrigue ... I urge you to enact such laws at the earliest possible moment and feel that in doing so I am urging you to do nothing less than save the honor and self-respect of the nation. Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out. They are not many, but they are infinitely malignant, and the hand of our power should close over them at once. They have formed plots to destroy property, they have entered into conspiracies against the neutrality of the Government, they have sought to pry into every confidential transaction of the Government in order to serve interests alien to our own. It is possible to deal with these things very effectually. I need not suggest the terms in which they may be dealt with."

- From President Woodrow Wilson’s “State of the Union Address December 7, 1915”

The Espionage Act of 1917 was passed on June 15, 1917 shortly after the United States entered into World War I. The federal law made it a crime to interfere, in any way, with the war effort, including disrupting military recruitment or aiding other nations at war with the U.S. However, the law had unexpected consequences with regards to the First Amendment, and many in opposition of the Espionage Act saw it as a government attempt to suppress and punish what was deemed to be unpopular speech. The Act also gave the Postmaster General authority to confiscate or refuse mail publications that he deemed to be in violation of the prohibitions.

Less than a year later, the law was extended and a set of amendments, generally called the Sedition Act of 1918, called for greater punishments and wider prohibitions. The Sedition Act prohibited many forms of speech including, “any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States… or the flag of the United States, or the uniform of the Army or Navy." Historians report that between the Espionage Act and its amendments more than one thousand convictions were carried out.

Although the controversial Sedition Act amendments were repealed in 1921, many of the original provisions of the Espionage Act remain, codified under U.S.C. Title 18, Part 1, chapter 37.

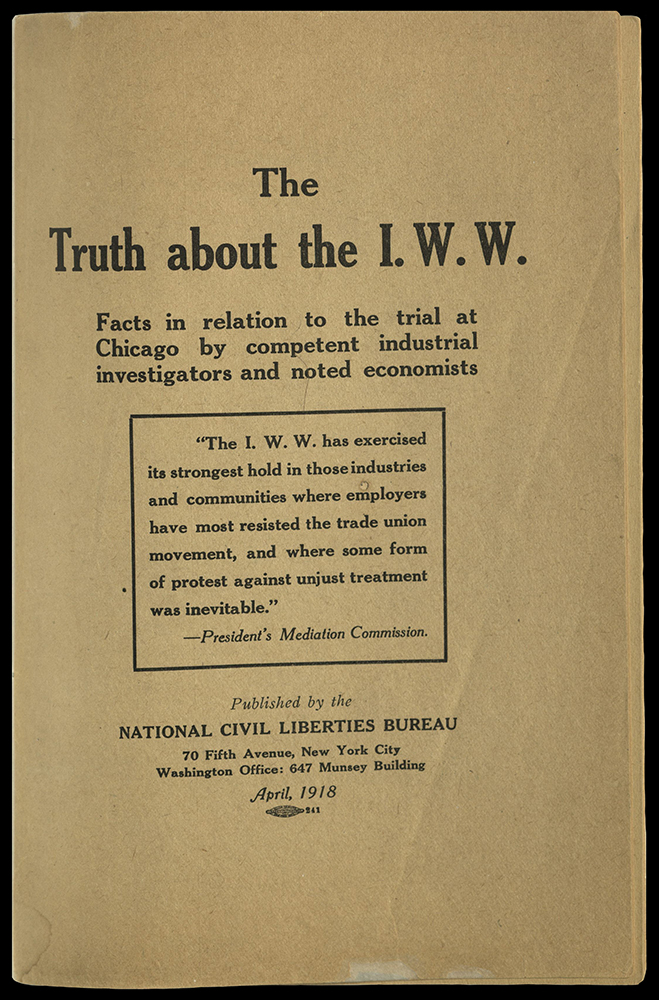

THE TRUTH ABOUT THE I.W.W.

American Civil Liberties Union

New York, NY : National Civil Liberties Bureau, 1918

HD8055 I5 A7 1918

The National Civil Liberties Bureau (CLB), later known as the American Civil Liberties Union, was co-founded in 1917 by Roger Nash Baldwin and Crystal Eastman, Max Eastman’s sister. Early on, the CLB’s primary focus was on supporting conscientious objectors during World War I, freedom of speech, anti-war speech, and speech within the labor movement in particular – issues that had become centers of conflict during the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.

Crystal Eastman was an American lawyer, antimilitarist, feminist, socialist, and journalist, best remembered as a leader in the fight for women’s suffrage. With her brother, she edited the radical arts and politics magazine the Liberator. She was also the co-founder of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Eastman resigned from her role in the CLB due to health issues, allowing Baldwin to assume sole leadership. In 1920, Baldwin reorganized under the name, American Civil Liberties Union and while there were other groups which focused on civil rights, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the ACLU was the first which did not represent a particular group of persons, or a single theme.

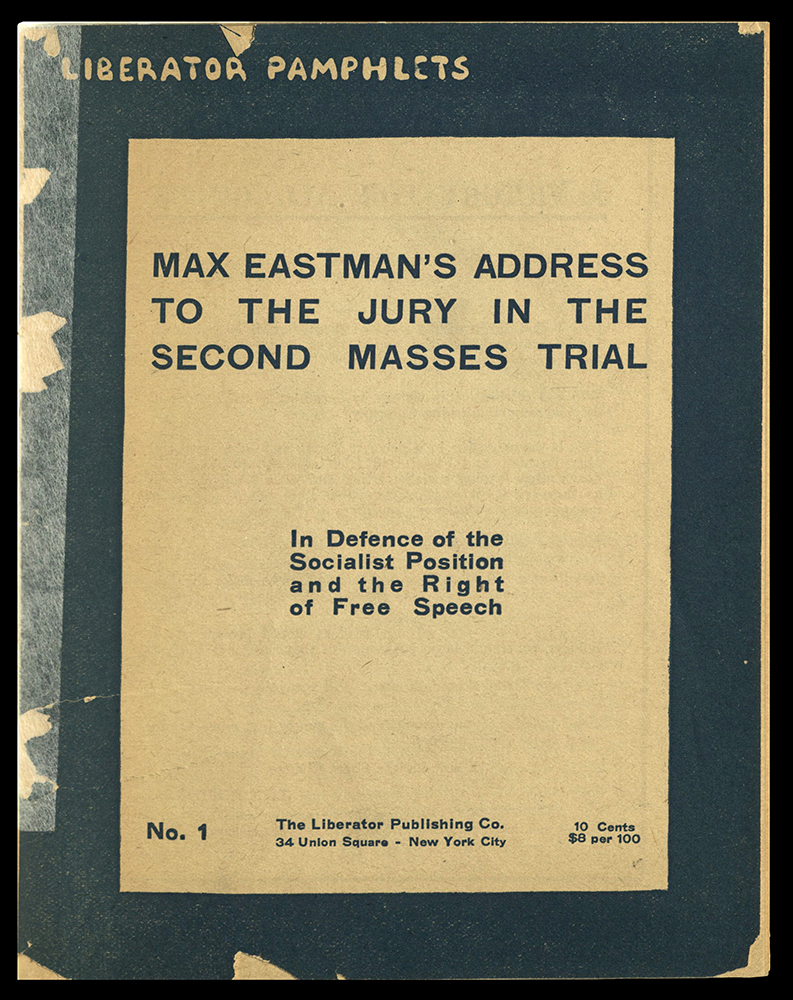

MAX EASTMAN'S ADDRESS TO THE JURY IN THE SECOND MASSES TRIAL

Max Eastman (1883 – 1969)

New York, NY : Liberator Publishing Company, 1918

HX86 E37

In the Fall of 1918, Max Eastman faced a jury in a Manhattan courtroom with the mission of defending himself and fellow contributors to the Masses against indictment under the Espionage Act. His speech stunned the courtroom, and with eight dissenting votes, no verdict was reached. Quickly, a pamphlet version of the speech, titled “Address to the Jury in the Second Masses Trial: In Defense of the Socialist Position and the Right of Free Speech,” was printed and circulated around the country, under the moniker of Eastman’s new magazine, the Liberator. Eastman argued in his address that the law had less to do with “espionage” and much more with the authority of censorship.

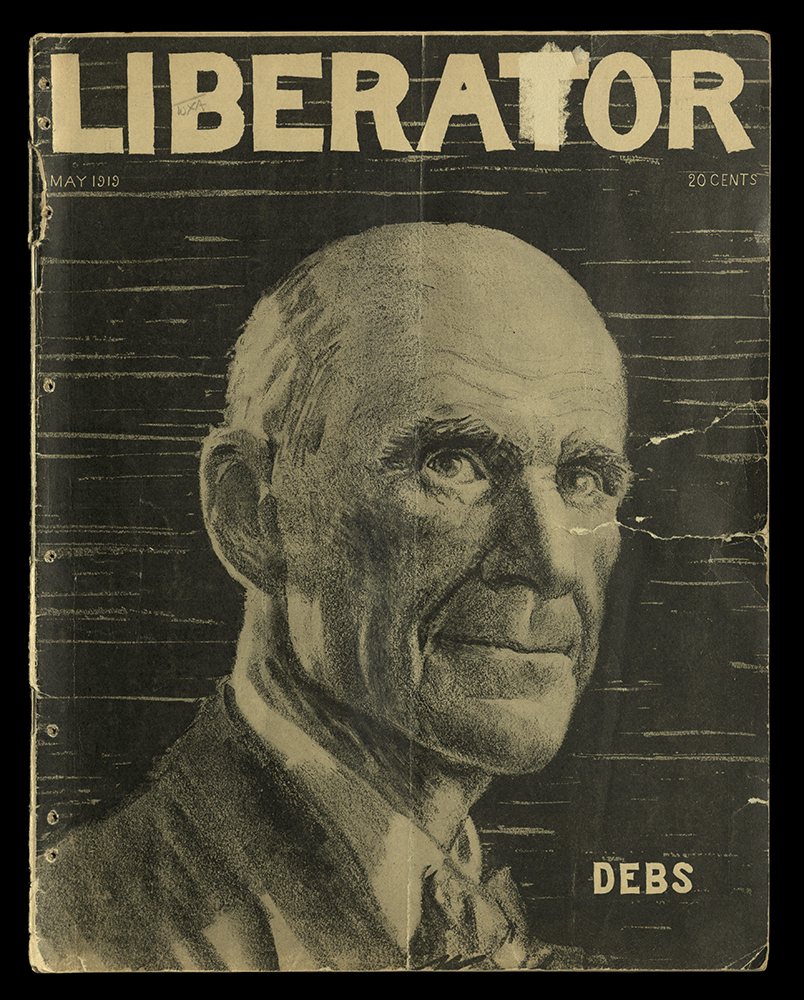

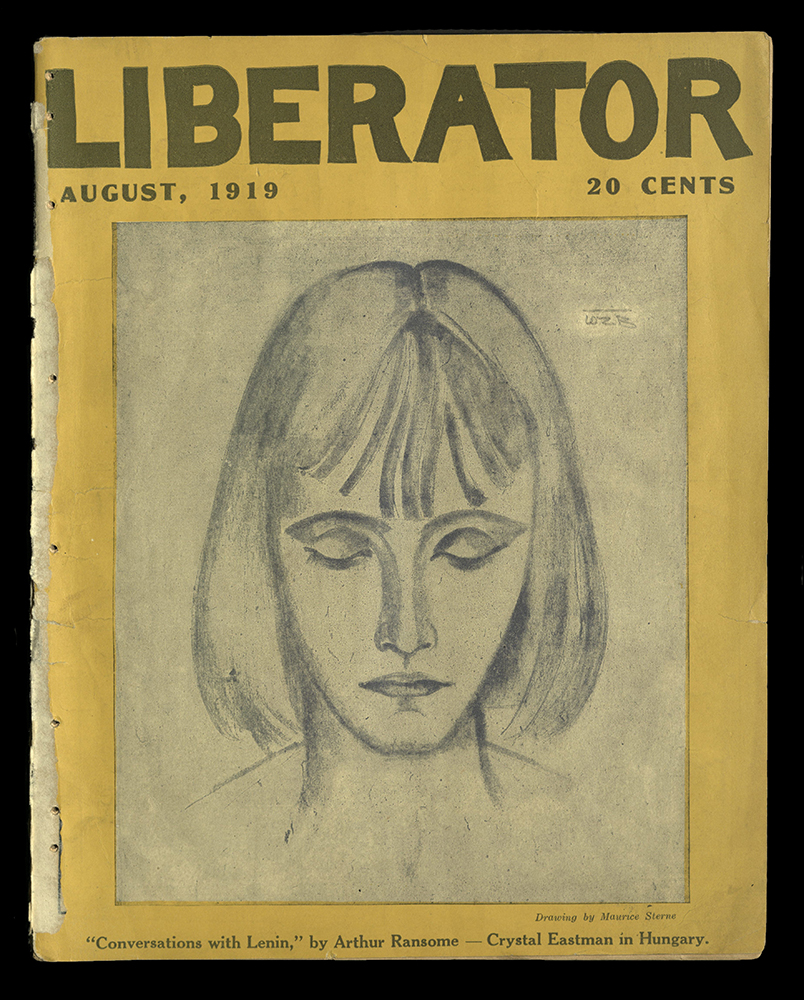

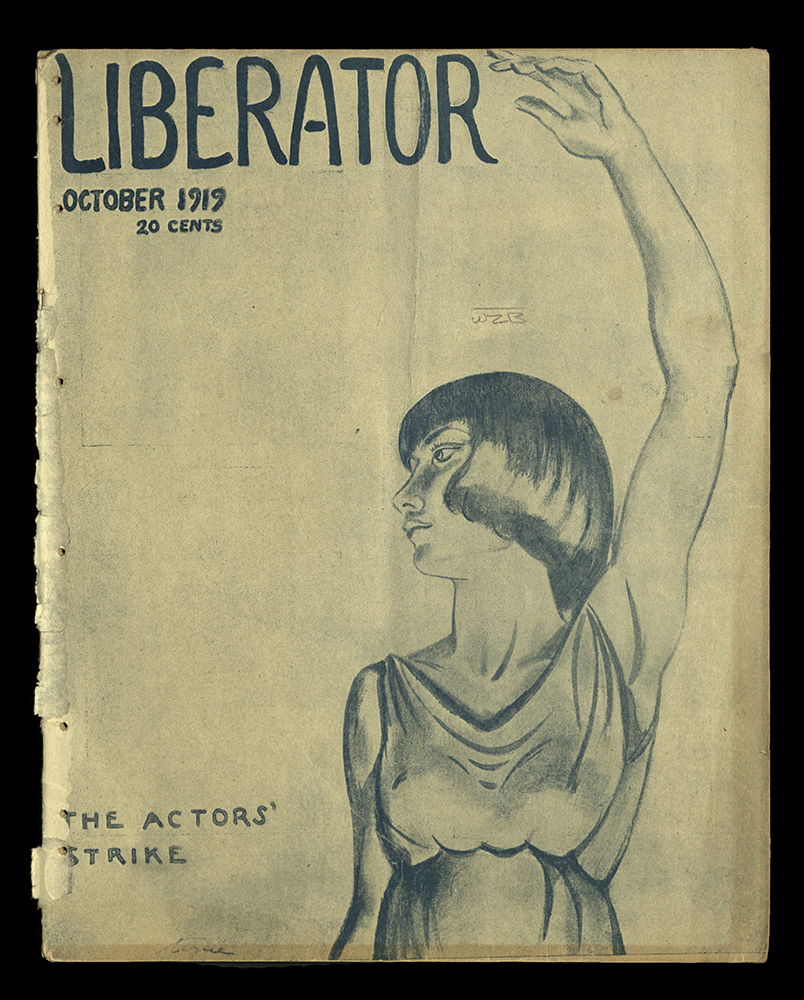

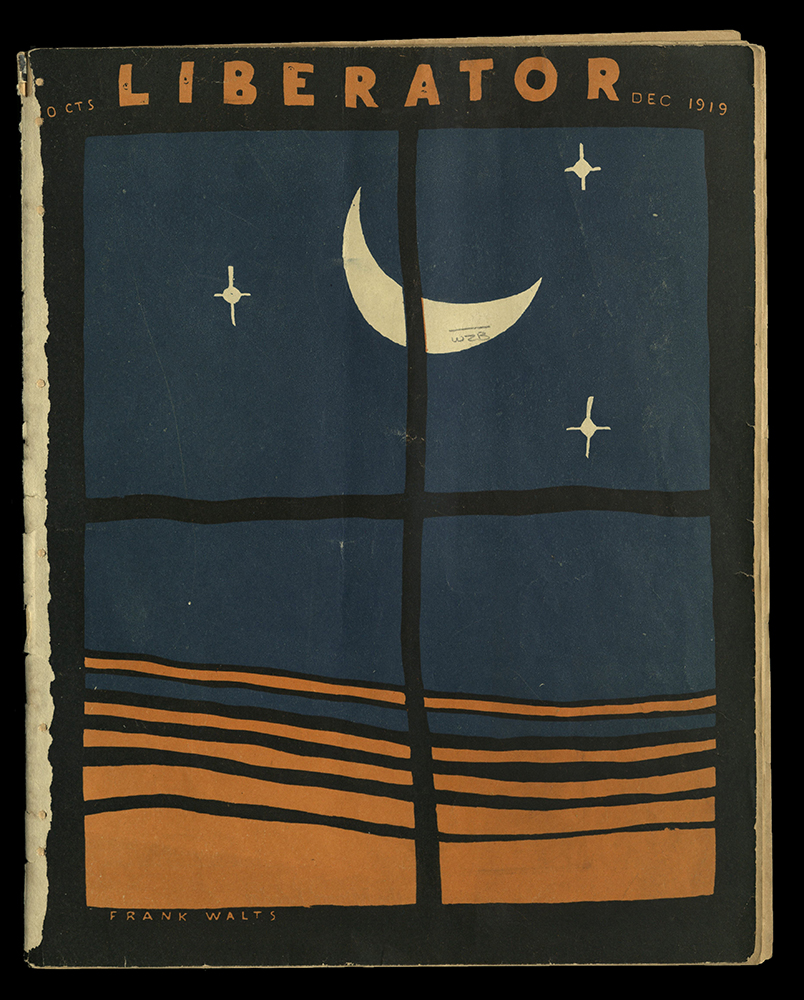

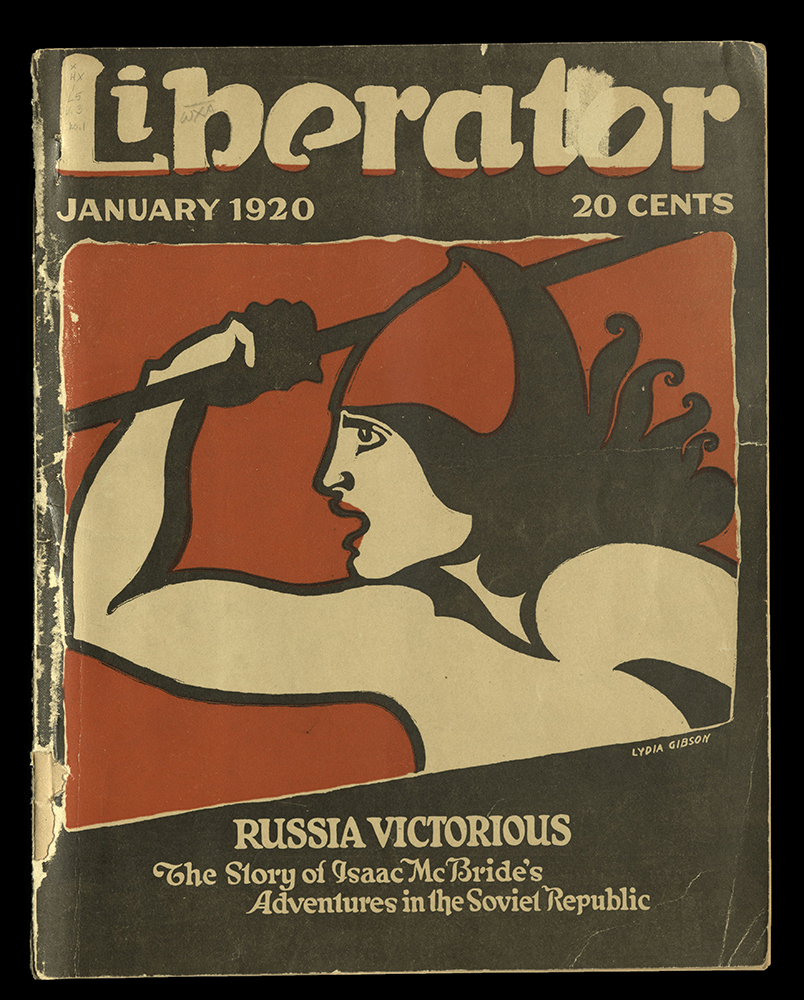

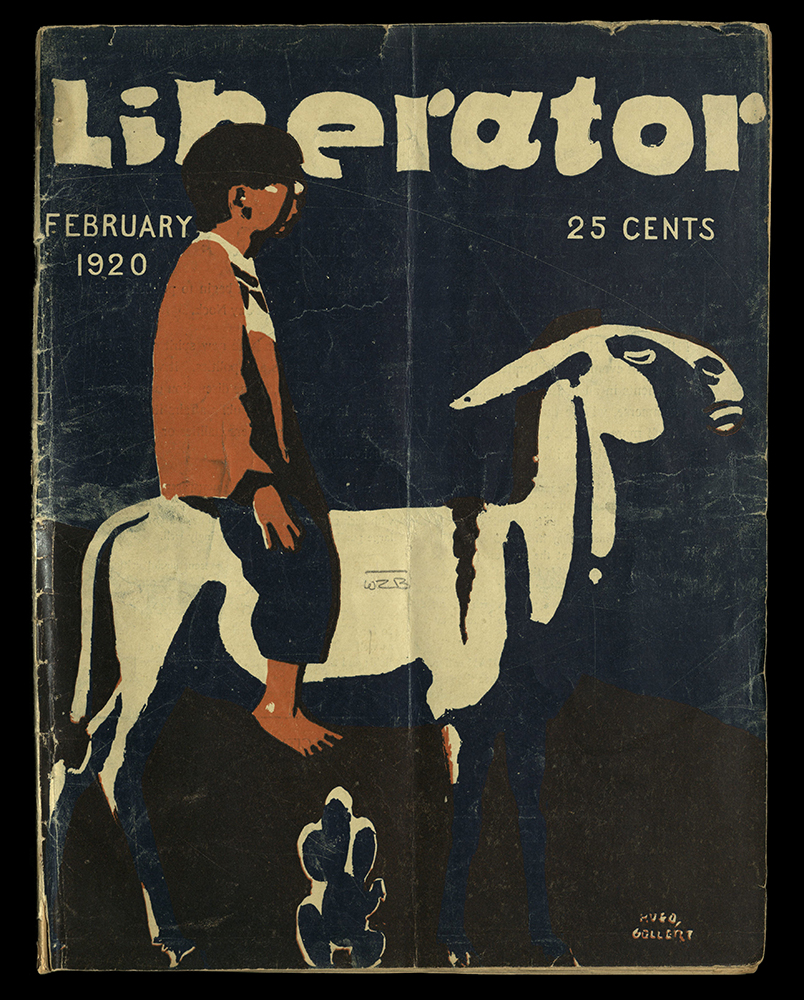

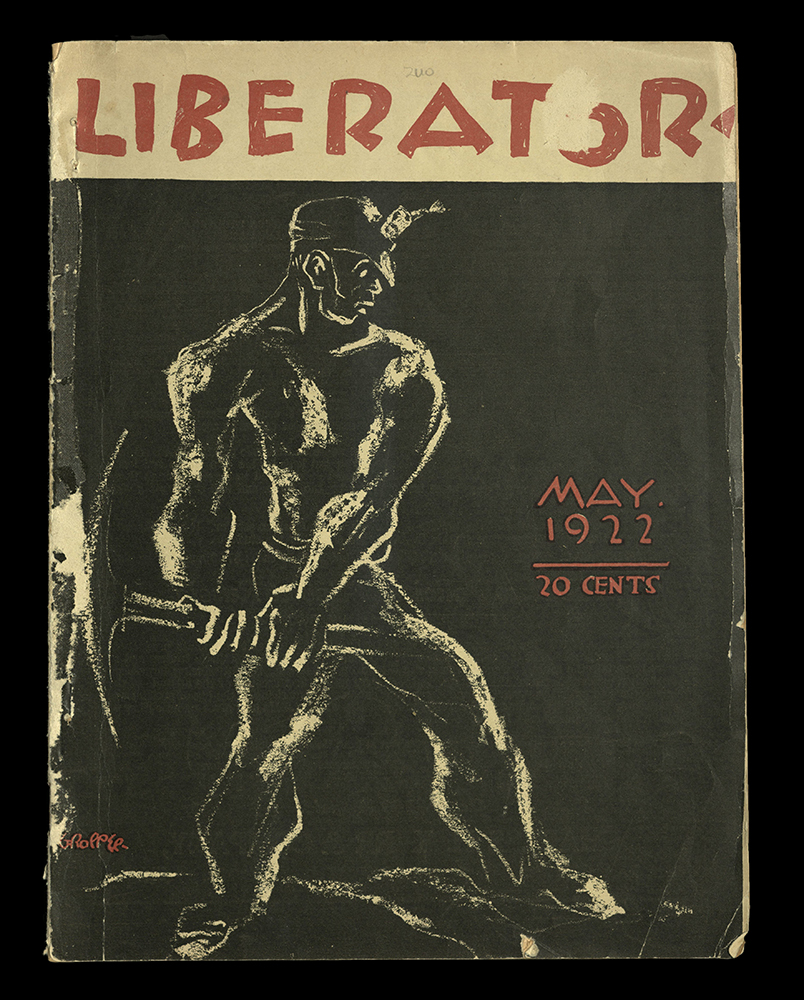

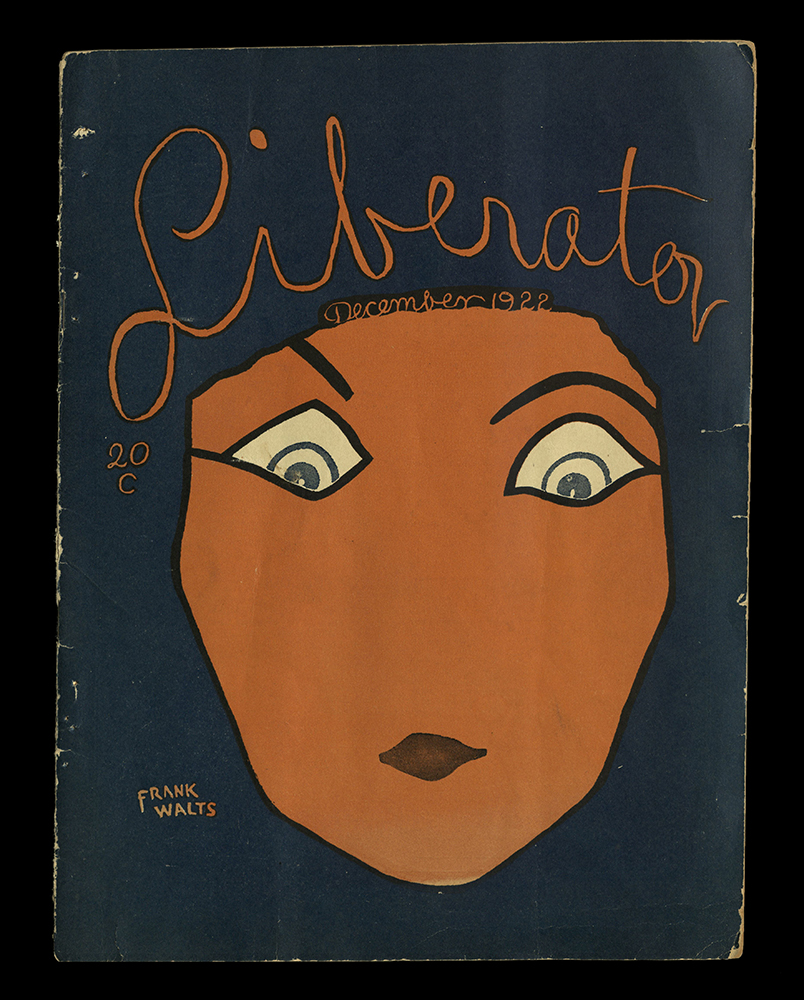

LIBERATOR

New York: The Liberator Publishing Co., Inc., 1918

HX1 L5

Liberator began publication under the editorship of Max Eastman (1883-1969) in March 1918. It was published to take place of another American radical periodical, the Masses, which had been shut down by the United States government in December 1917 as offensive and contrary to mailing regulations during World War I. The Masses was anti-war. Many of its editors and writers later contributed to Liberator.

Liberator fused politics, art, poetry and fiction. The international reporting that came out of it was among the best in the United States, including stories filed by the legendary John Reed (1887-1920) from Soviet Russia. Other contributing artists and writers included e. e. cummings (1884-1962), John Dos Passos (1896-1970), Ernest Hemingway (1999-1961), Helen Keller (1880-1968), and Carl Sandburg (1878-1967). Almost every important radical or liberal literary figure of the time was represented in it.

The Liberator began to take a definite political line. In 1922, Eastman left the Liberator, and the Communist Party of America (CPA) took it over. It merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial to form Workers Monthly, an organ of the CPA, in November 1924. Prime movers Max Eastman and Floyd Dell (1887-1969) left the editorial board, and Robert Minor (1884-1952) and other closer followers of the Communist line replaced them. The publication, from its evocative cover art, to the typesetting required to meet the standards of its writers, was expensive to produce. To offset cost, Eastman used cheap newsprint, resulting in a publication that is incredibly fragile. Few copies survive.

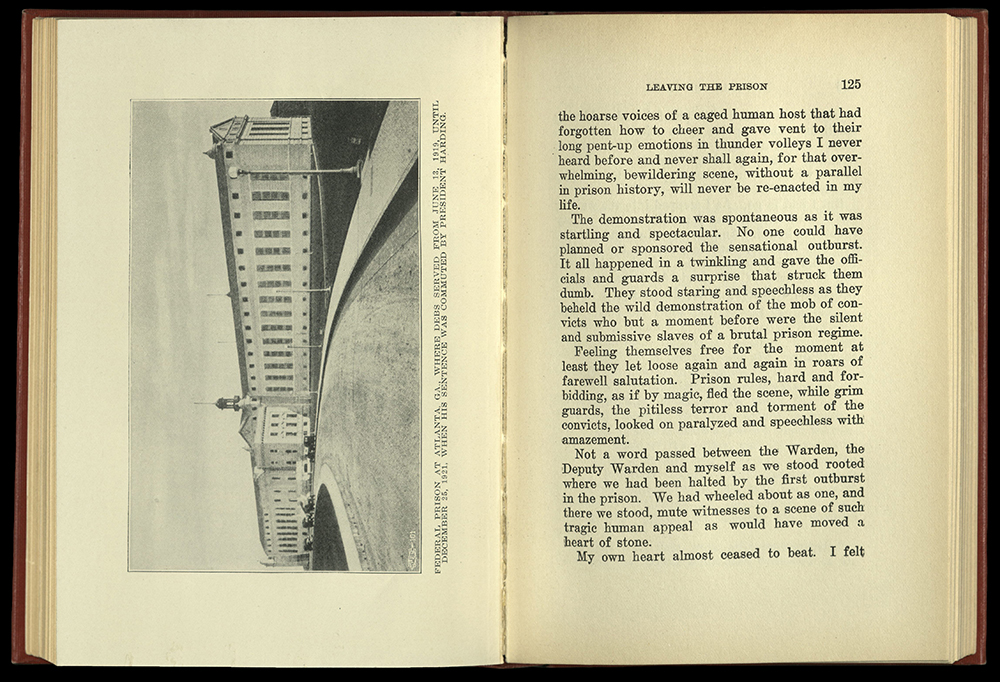

WALLS AND BARS

Eugene V. Debs (1855 – 1926)

Chicago, IL : Socialist Party, 1927

HX84 D3 A33

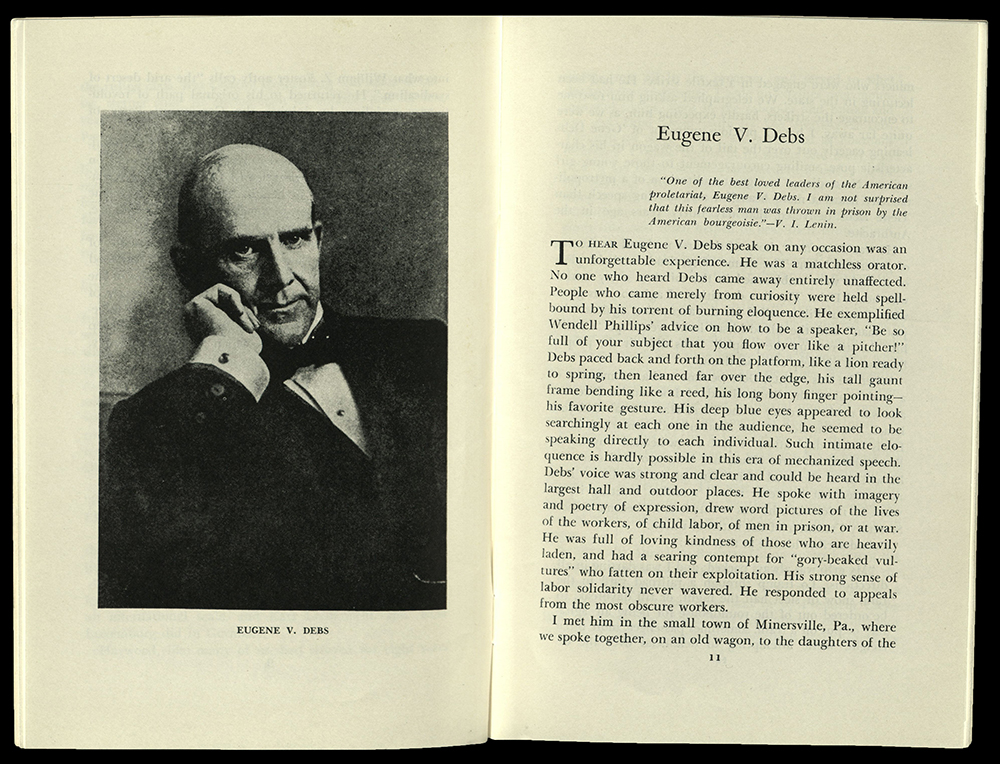

Eugene Victor Debs was an American political activist, trade unionist, and one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World, in addition to being the five-time presidential candidate of the Socialist Party of America. During the late nineteenth century, Debs was an instrumental figure in the founding in the American Railway Union (ARU), of one of the country’s first industrial unions. In 1894, Debs led an ARU boycott, which became known nationwide as the Pullman Strike. The strike included more than 250,000 workers across 27 states, and affected most of the railway lines west of Detroit, many of which were responsible for transporting the mail. In order to keep the mail running, President Grover Cleveland called on the army to break the strike. Debs was arrested and convicted on federal charges, for which he spent six months in prison.

Decades later, Debs delivered a speech denouncing American participation in World War I at a public park in Canton, Ohio. For “The Canton Speech,” as it was later called, Debs was arrested and charged with ten counts under the Sedition Act for intending to “cause and incite insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny and refusal of duty in the military,” as well as for trying “to obstruct the recruiting and enlistment service of the United States.” While in prison at the United States Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, Debs wrote a series of columns deeply critical of the prison system. These columns first appeared in the Bell Syndicate, and later published posthumously with additional chapters as Wars and Bars. The original manuscript of Debs’ first and only book is held in the Thomas J. Morgan Papers in the Special Collections department of the University of Chicago Library.

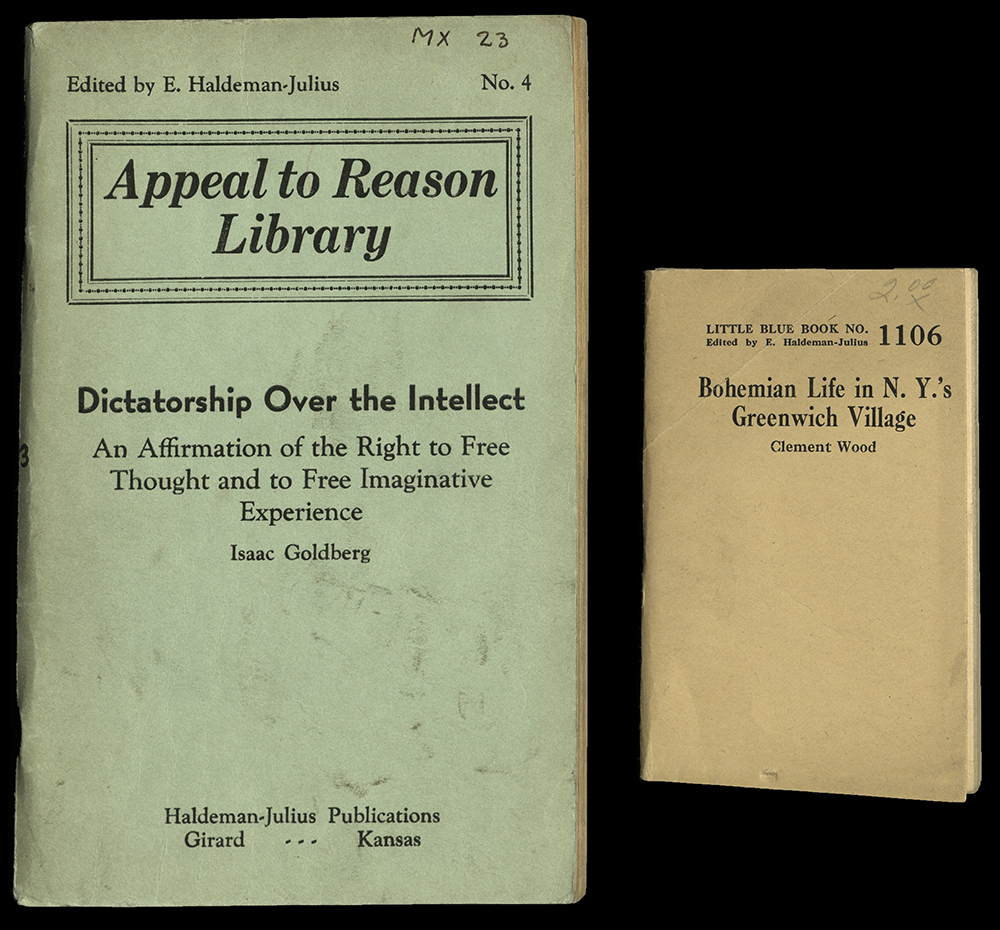

HALDEMAN-JULIUS PUBLICATIONS

The Little Blue Books were a popular series of small staple-bound books published from 1919-1978, by the Haldeman-Julius Publishing Company, located in Girard, Kansas. After purchasing a publishing house from his employer, Appeal to Reason – a socialist weekly – Emanuel Haldeman-Julius and his wife, Marcet, set out to publish small, low-price paperback pocketbooks for both the working and educated classes. In addition to classic works of literature, their goal was to distribute pamphlets that included a wide range of ideas: from common-sense knowledge to various radical viewpoints of the time, including essays about abortion, homosexuality and race. The small 3 ½ by 5-inch pamphlet fit perfectly into a working man’s back or shirt pocket and could be shared among friends, family and colleagues. With a starting subscription of fifty titles (at 10 cents a book), Haldeman-Julius began printing at a rate of 24,000 copies a day. Over the years, the name of the pamphlets changed, at times known as the People’s Pocket Series, the Appeal Pocket Series, the Ten and Five Cent Pocket Series, and finally in 1923, The Little Blue Book Series. Despite the books’ popularity, and Haldeman-Julius being dubbed the “Henry Ford of Literature,” the Little Blue Books came under government criticism after World War II, likely due to their inclusion of subjects such as socialism and atheism. After an FBI investigation and tax evasion conviction, the popularity of the books declined rapidly, finally coming to an end after the printing plant and warehouse was destroyed by fire in 1978.

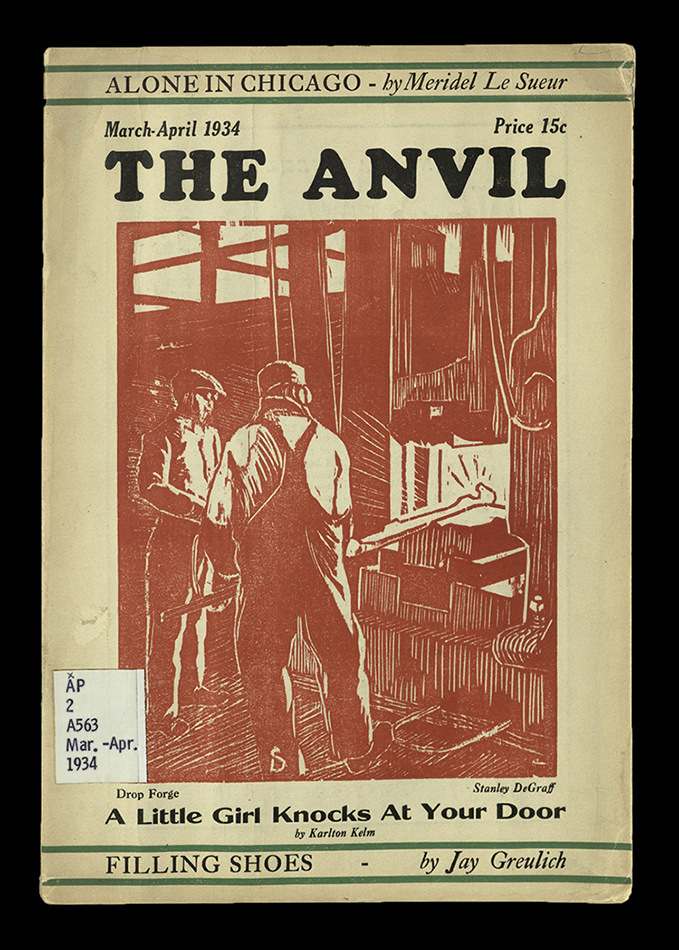

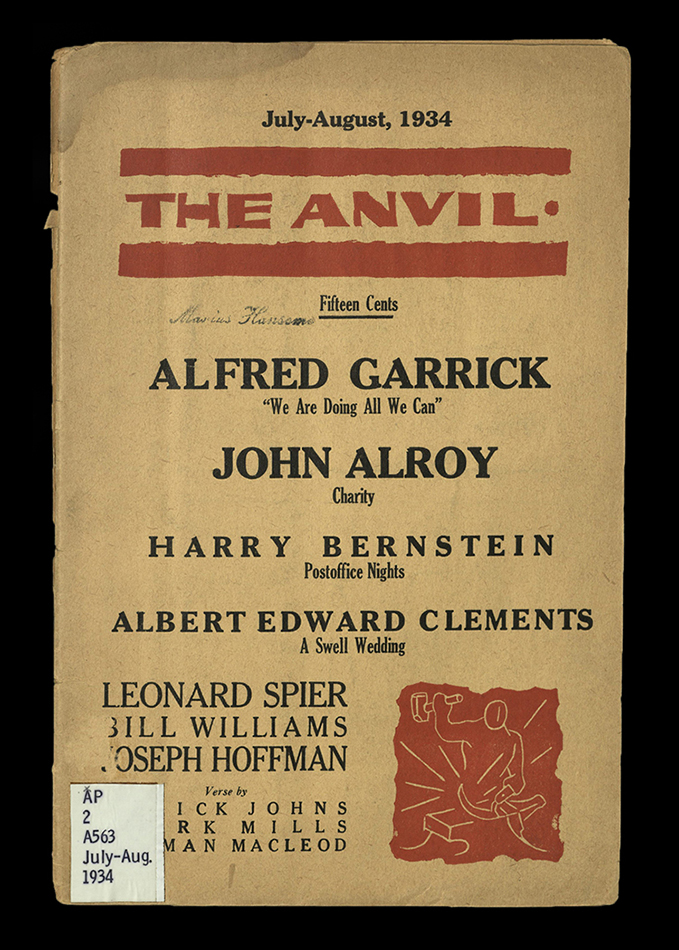

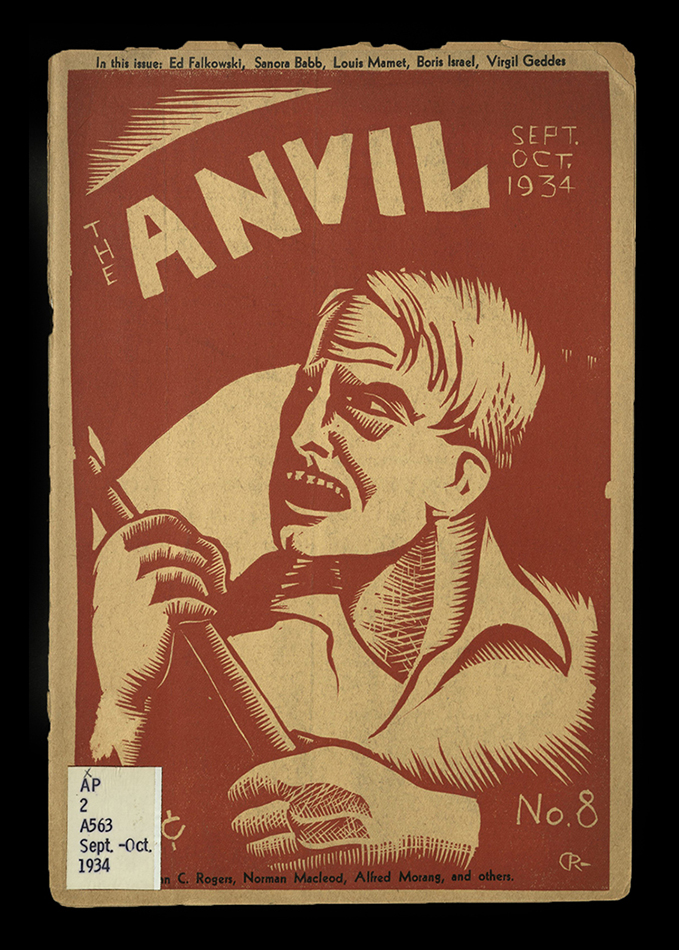

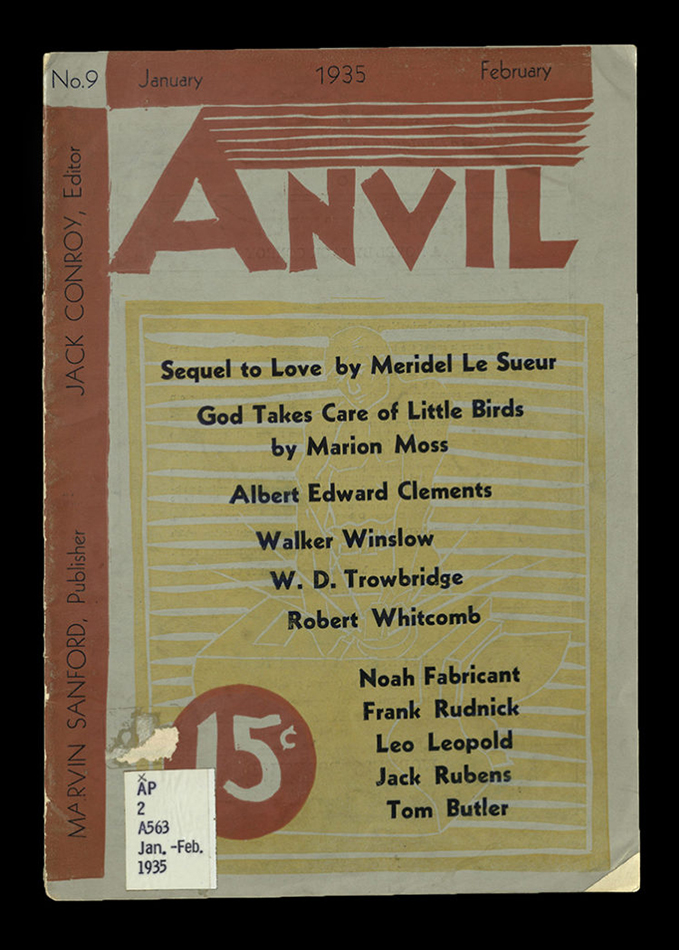

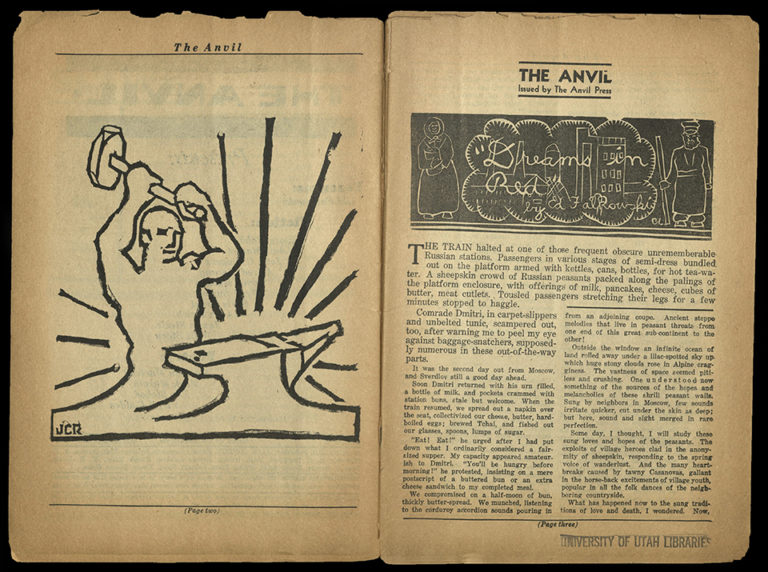

THE ANVIL PRESS

Jack Conroy was born to Irish immigrants in a coal mining camp called Monkey Nest, outside of Moberly Missouri. Conroy joined up with the Rebel Poets — a group of proletarian writers loosely connected with the Industrial Workers of the World. Within two years, his writing and enthusiasm landed him an editorial position with the journal Rebel Poet, yet another proletarian journal that originated during the 1930s. However, Conroy believed that the notions of social injustice within Rebel Poet were too ill-defined to attract the ordinary reader.

Conroy understood that the proletariat were more sensitive to the enticements of mass culture and consumerism than slogans such as “Workers Unite!” He understood that the abstract analyses of Marxist theory in Rebel Poet likely deterred rather than engaged new readership. He wanted a publication molded from the experiences of young writers from the mills, mines, forests, factories and offices of America; a publication that portrayed an honest, rather than simplistic, view of the working-class experience. Most of all, Conroy wanted to provide a new outlet for worker-reader so he could “wean” them away from romance novels and from escapist fiction that had nothing in common with their lives. With all this in mind, the Anvil was born in 1933.

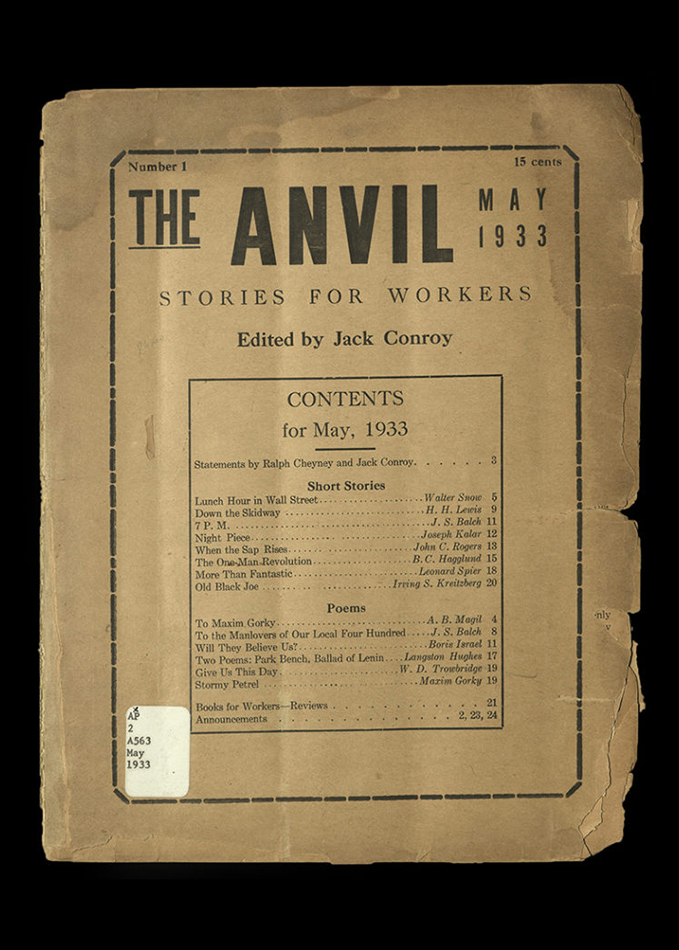

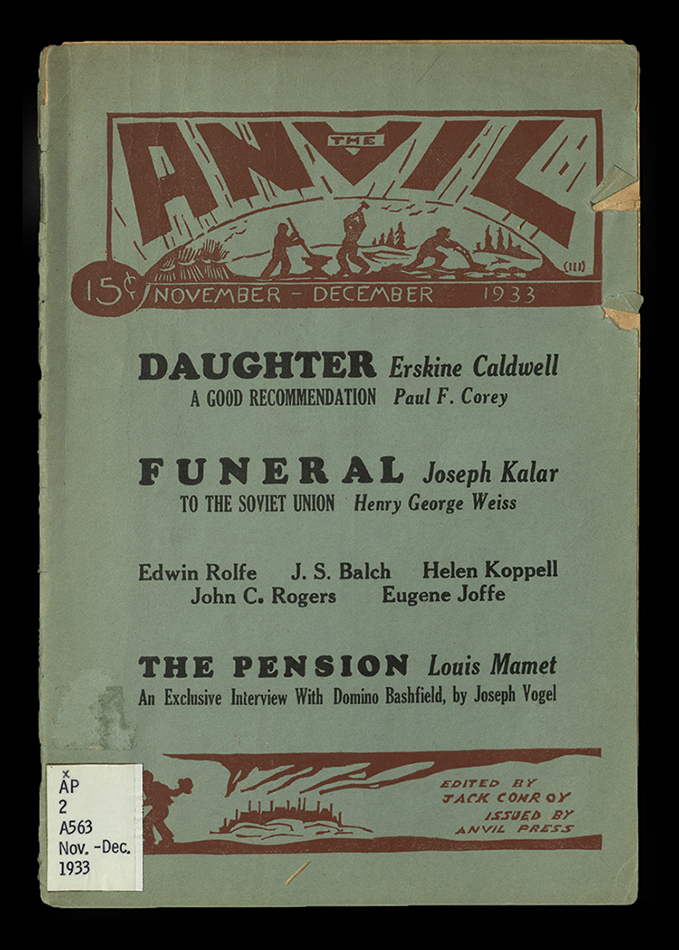

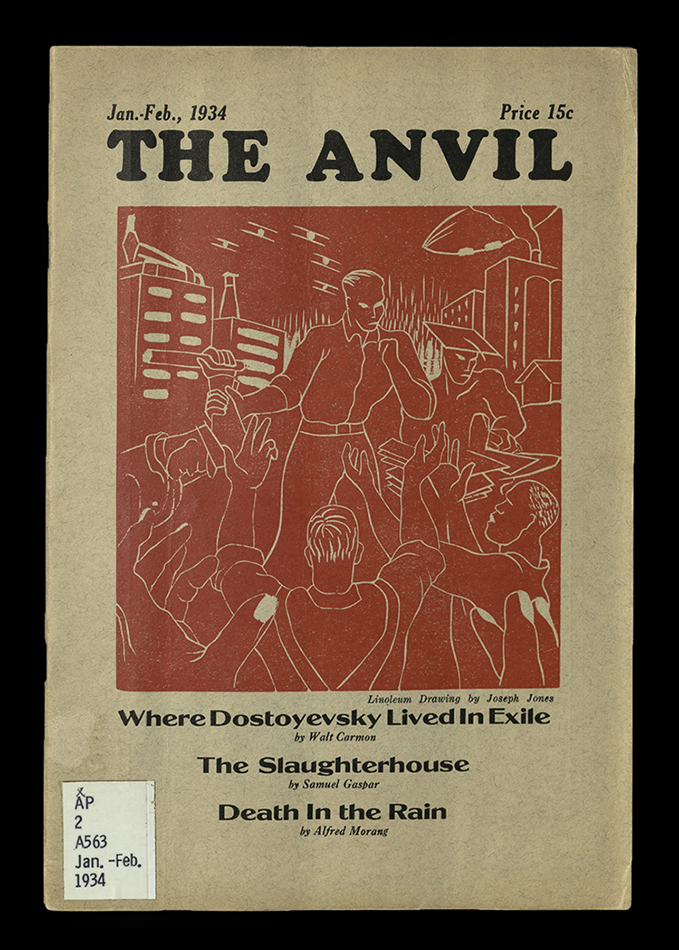

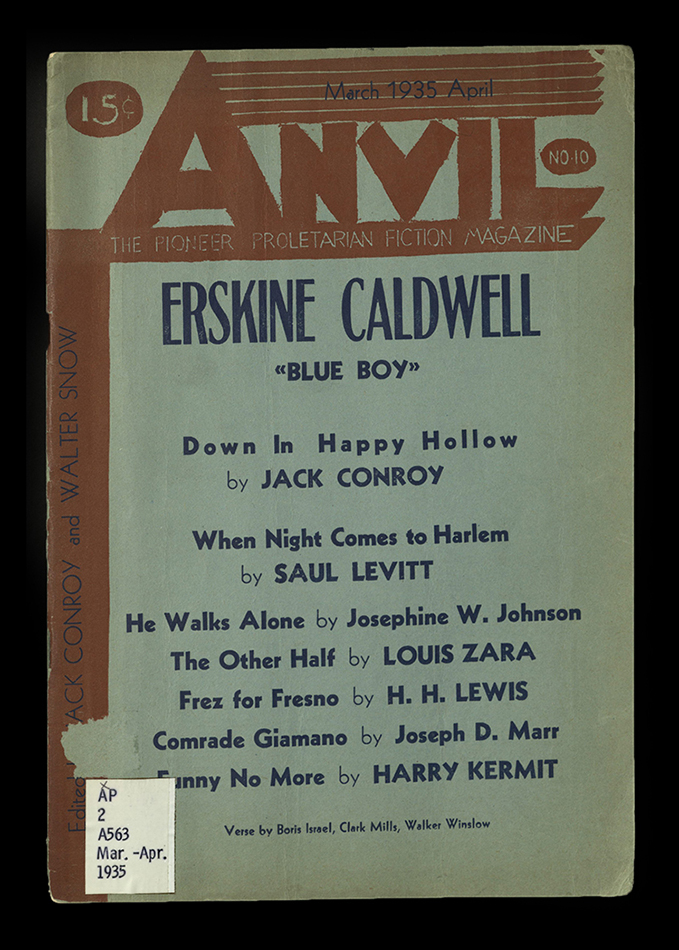

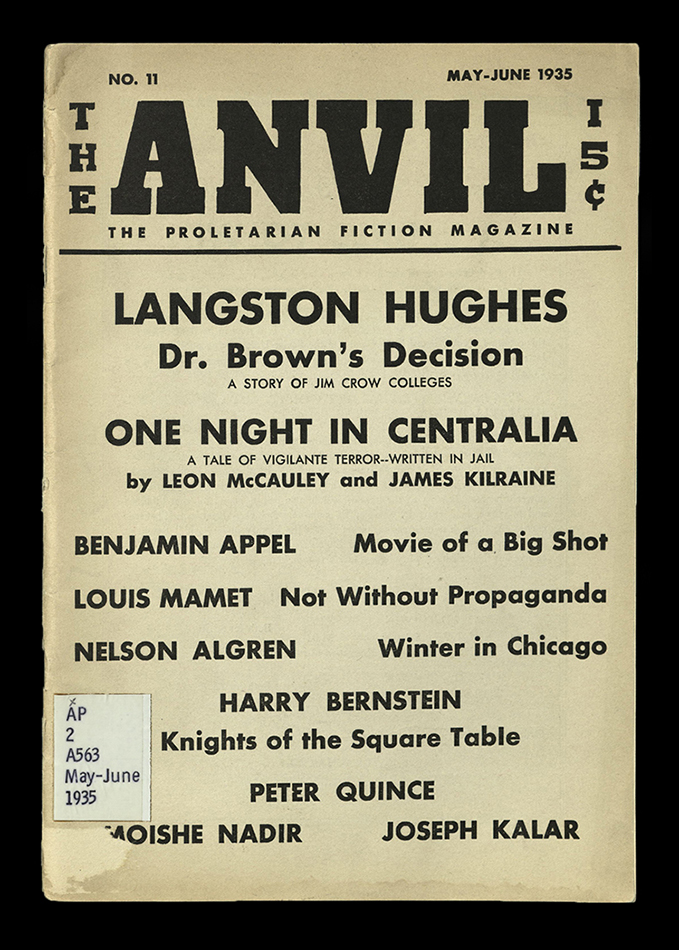

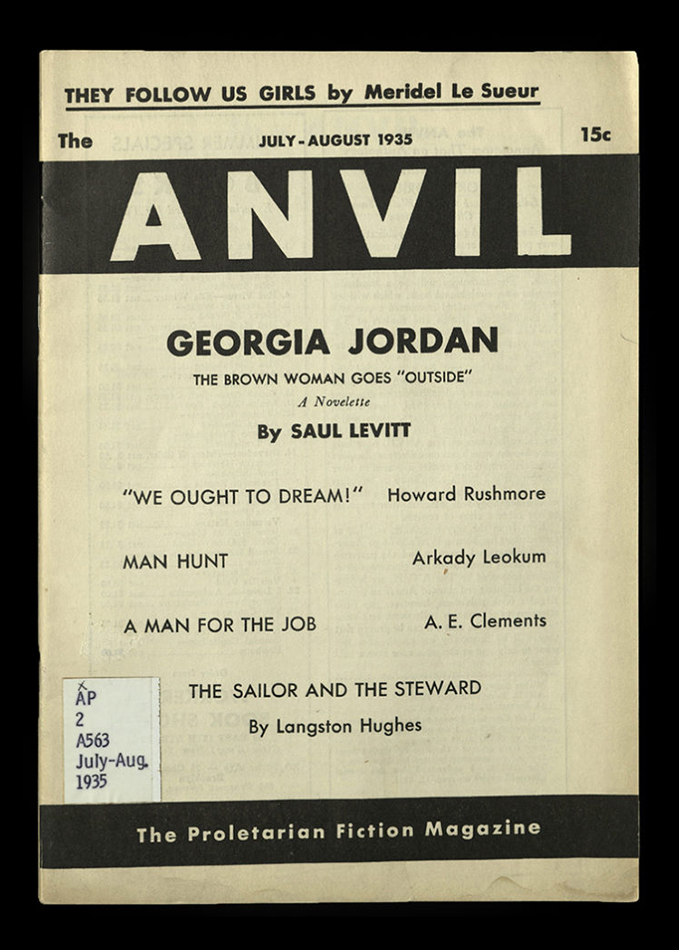

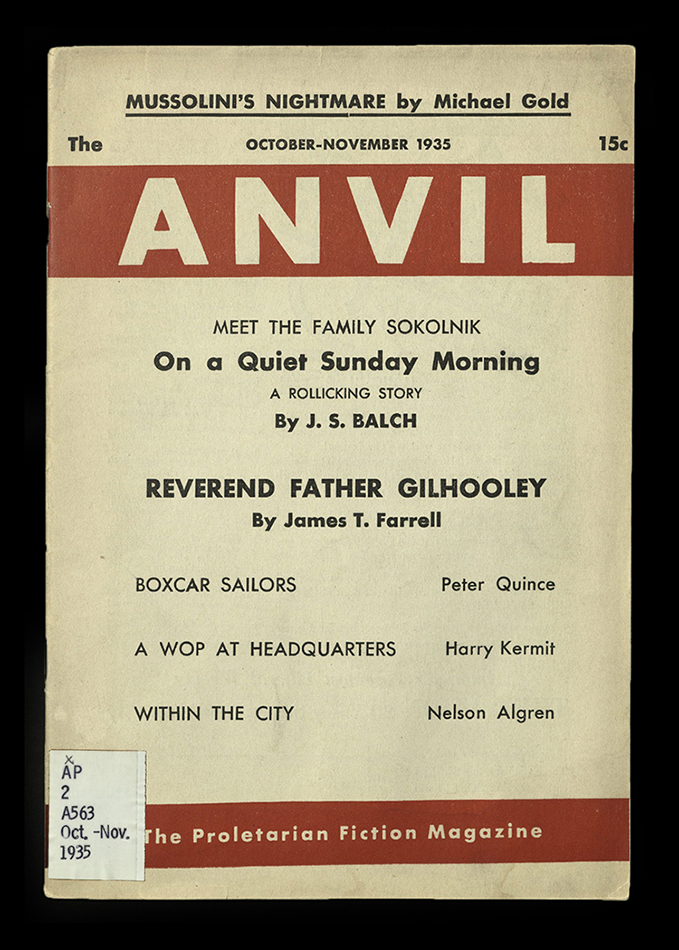

ANVIL

Missouri: Anvil Press, 1933-1935

AP2 A563

The title Anvil evoked the worker’s world: strength, firmness, raw material, the force of physical labor, the shaping of a new world. These images also complimented the magazine’s slogan: “We prefer crude vigor to polished banality.” As word spread through factories in the Midwest and leftist bookstores on the East Coast, Anvil’s subscription list reached 250 people (one year’s subscription was $1.00). The first issue was printed in a run of 1,000 — two hundred copies were exchanged with other magazines and the rest were sold at 10 cents each.

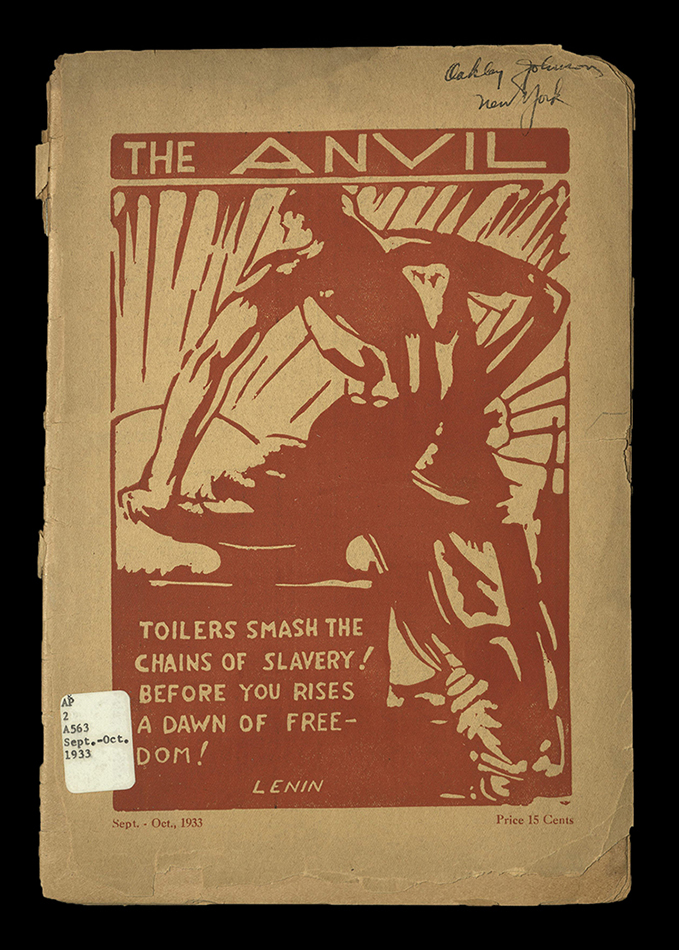

Rare Books copy of the second issue of Anvil inscribed by Oakley Johnson, socialist activist and founding member of both the Communist Party of America and the Proletarian Party of America. During the Fall of 1933 (when the issue was released), Johnson became the Communist candidate for the New York State Assembly in the 9th Assembly District of New York County.

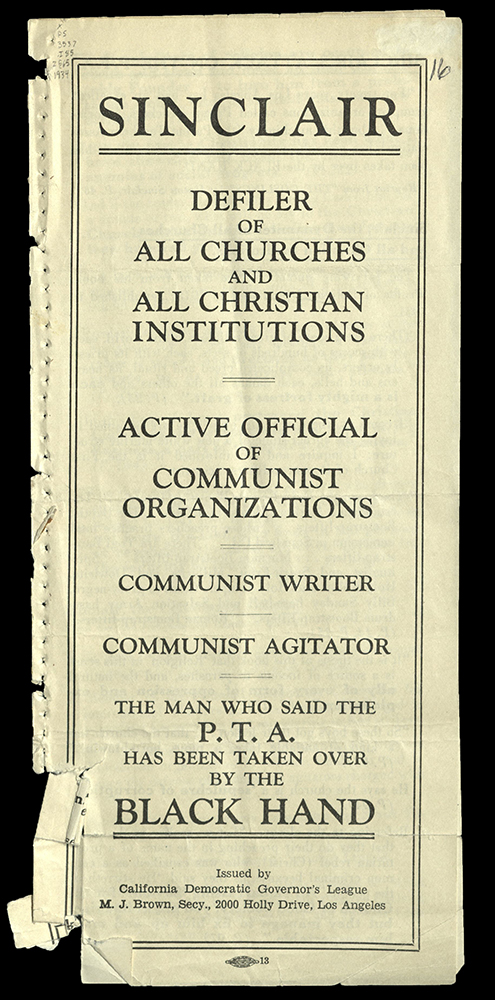

SINCLAIR, DEFILER OF ALL CHURCHES ...

SINCLAIR, DEFILER OF ALL CHURCHES ...

California Democratic Governor’s League

Los Angeles, CA : California Democratic Governor’s League, 1934

PS3537 I85 Z565 1934

Upton Sinclair was an American writer most known for his muckraking novel, The Jungle. During the 1920s, however, Sinclair relocated to southern California to begin a career as a politician and activist. In a suburb of Los Angeles, Sinclair founded the state’s chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, and ran twice (unsuccessfully) for the Governor of California as a nominee for the Socialist Party. With the election of President Roosevelt in 1932, Sinclair was encouraged to run again, this time switching his affiliation to the Democratic Party in 1933. Sinclair’s campaign, The End Poverty in California movement (EPIC) was laid out in his 1933 book, I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty. In this pamphlet he called for increased public works programs and tax reforms, in addition to guaranteed pensions. Unfortunately, he did not receive full support from the party establishment as the EPIC plan was deemed too radical.

In addition, Sinclair and the EPIC movement faced major opposition by the Republican Party, as well as major media figures in print and on screen. For the first time in history, a major political campaign was turned over to outside advertising, publicity, media and fundraising consultants – which include Whitaker and Baxter’s California League Against Sinclairism. The coordinated opposition against Sinclair caused him to fall behind Frank Merriam in the polls. On November 6, 1934 Sinclair lost with only 37.8% of the votes. Although Sinclair was defeated, two dozen candidates, who also ran on the EPIC platform, were elected to state legislature that year. Furthermore, EPIC is recognized as having been influential in shaping Roosevelt’s New Deal programs.

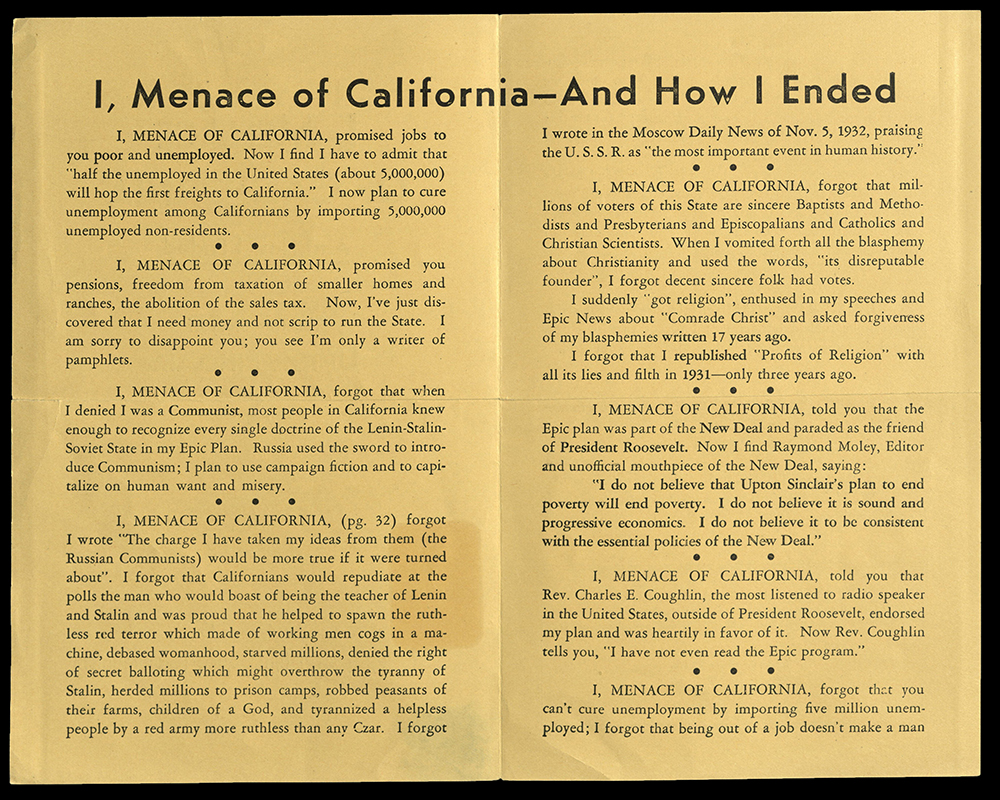

I, MENACE OF CALIFORNIA

California League Against Sinclairism

San Francisco, CA : 1934

PS3537 I85 Z53

During the California gubernatorial race in 1934, husband-and-wife team, Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter were hired by former lieutenant governor, Frank Merriam, to help him win the election against the writer and Democrat candidate, Upton Sinclair. Based in California, Whitaker and Baxter started Campaigns, Inc., the first political consulting firm in the United States. The firm worked on a variety of political issues and, together, they developed new strategies and tactics that are still being used in today’s political campaigns.

Using oppositional research tactics, Whitaker and Baxter were able to pore through all of Sinclair’s previous writings in order to find quotes that they could use against him in advertisements and media campaigns. In addition, they organized a bipartisan group known as the California League Against Sinclairism. Painting Sinclair as a communist sympathizer, and the EPIC movement as socialist agenda, Whitaker and Baxter were able to persuade the public vote. Ultimately, Sinclair attributed his defeat to the tactics used by Whitaker & Baxter, who he named as “The Lie Factory” in his post-election book, I, Candidate for Governor, and How I Got Licked.

“It is not the rate of mechanization or technological development that produces the poverty and unemployment. It is not the machines that produce the joblessness and misery. It is not overproduction of wheat that produced a bread famine among the poor. It is not overproduction of cotton and wool that makes men and women ragged and unclad. It is not excess of wealth produced that makes the producers penniless and unable to buy even a portion of their own product […] It is the ownership and control of the land and machinery of production by a social class that lives without working, through the persistency of social laws and customs that have been outgrown by the economic structure of society, that is the cause of the present world-wide unemployment and social misery…”

UNEMPLOYMENT AND THE MACHINE

C.B. Ellis

Chicago, Il : Industrial Workers of the World, 1934

HD6331 E43 1934

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in early March 1933, a quarter of the civilian labor force was unemployed. By the following winter, that number rose from fourteen million to eighteen million. Within the first three years of the Great Depression, the divisions among the upper and lower classes were stark and bitter. Economic disparity heightened tensions and highlighted social and political issues in the United States and abroad. The effects of land erosion and a growing insurgency among farmers and factory workers began to reshape the political and literary spectrum in America. In response to the “progressive slump into the slough of idleness, poverty, pauperism and misery,” C.B. Ellis, under the leadership of the Industrial Workers of the World, published Unemployment and the Machine. In this pamphlet, Ellis argues that neither the Industrial Revolution nor the popular theories of “overproduction” and “over-development” as the root cause of the economic crisis were to blame for the increasing disparity among the social classes.

1ST OF MAY

Socialist Labor Party

New York, NY : Socialist Labor Party, 1936

HX87 S6264 1936

The first of May is a national, public holiday celebrated in many countries all over the world as International Workers Day. Although it was officially established in 1889, its origins come from several years prior. The date was initially chosen by the American Federation of Labor in efforts to continue an ongoing campaign for the eight-hour work day in the United States, brought on by the Haymarket Affair that took place in Chicago in May 1886. The Haymarket Affair began as a general strike for the eight-hour work day, but when police came in to disperse the public assembly, a bomb went off, causing police to fire on the workers. Seven police officers and at least thirty-eight civilians were killed and more than two hundred people were injured. As a result, hundreds of labor leaders and sympathizers were arrested, with four executed by hanging. Because of the brutality of such events, labor organizers adopted a resolution for a "great international demonstration" in support of working-class demands. Since then, the first of May, or May Day, has been a focal point for demonstrations by a variety of socialist, communist and anarchist groups across the globe.

Featuring “Golden Jubilee of De Leonism, 1890-1940: Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the founding of the Socialist Labor Party.” Daniel De Leon was an American activist and early leader of the first United States socialist political party: The Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP) in 1890.

THE CONSTITUTION AND BY-LAWS OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY

Communist Party of the United States of America

New York, NY : Workers Library Publishers, 1938

JK2391 C5 A515

The Workers Party of America (WPA) was the original and legal name of organization used by the Communist Party USA until 1929. The party established its own printing house under the names International Publishers and Workers Library Publishers. While International Publishers were responsible for printing books, the Workers Library Publishers, based in New York City, focused on distributing propaganda pamphlets and official Workers Party magazines. By the end of the 1930s, pamphlets only made up about ten percent of the published titles.

THE MAVERICK AND MORNING STAR PRESS

“Are you willing to be sponged out, erased, cancelled,

made nothing?

Are you willing to be made nothing?

dipped into oblivion?

If not, you will never really change…”

— “Phoenix,” D.H. Lawrence

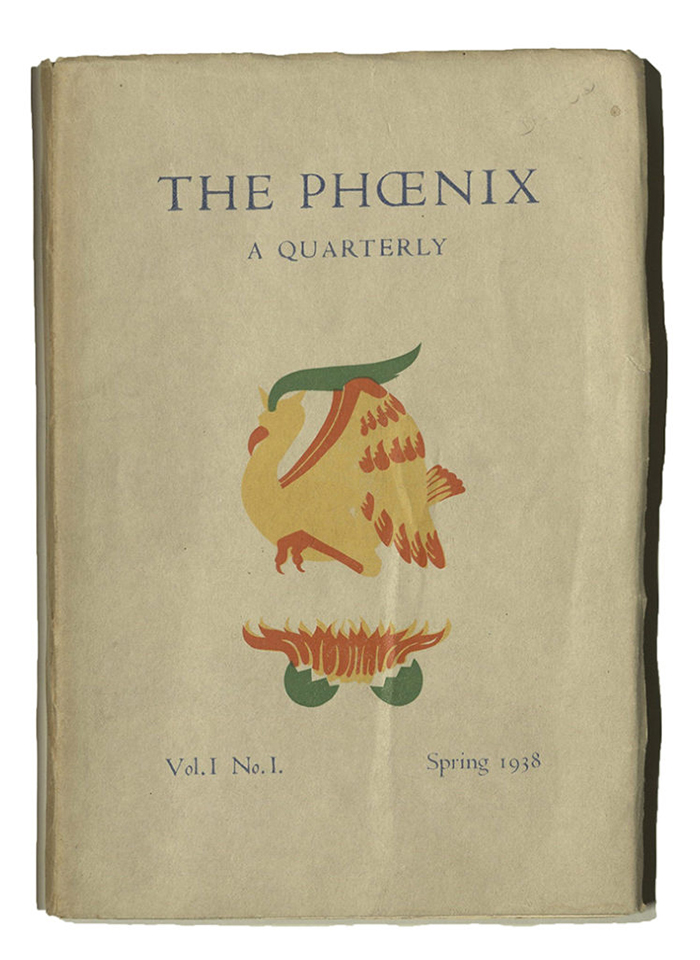

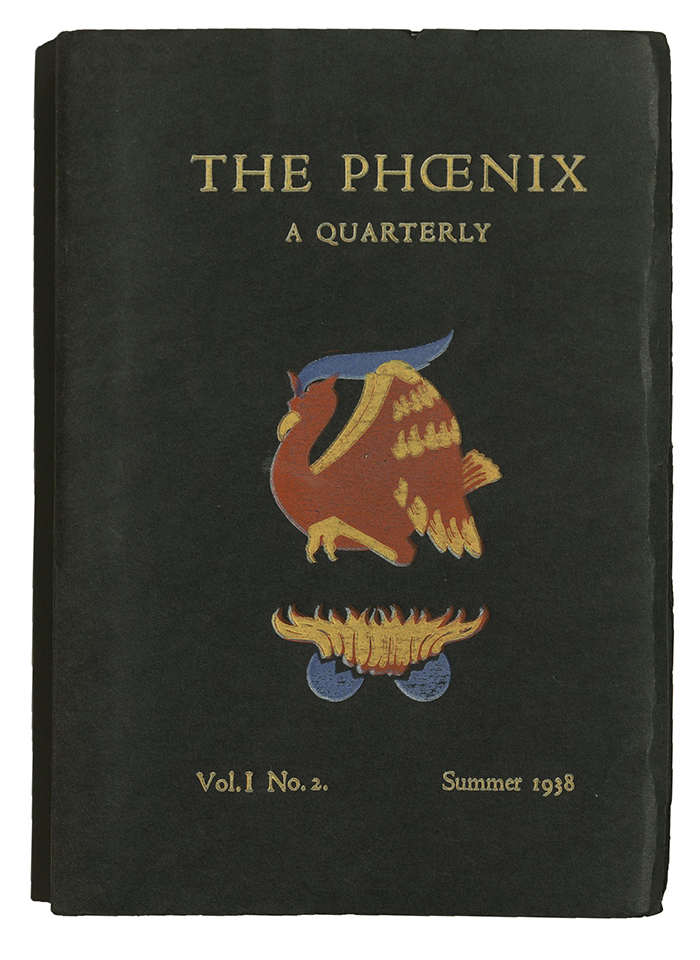

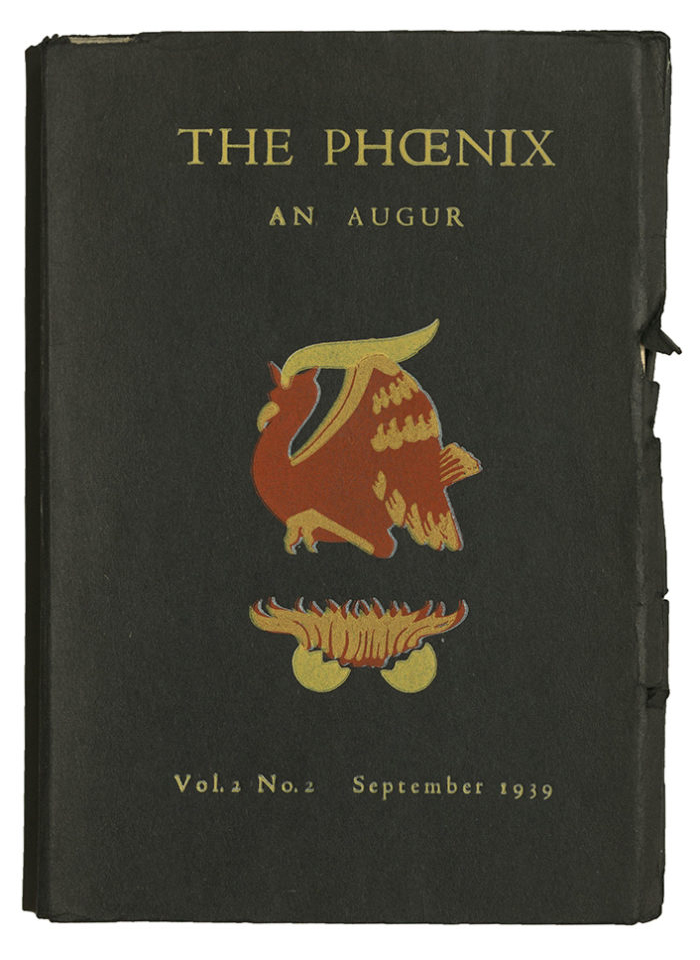

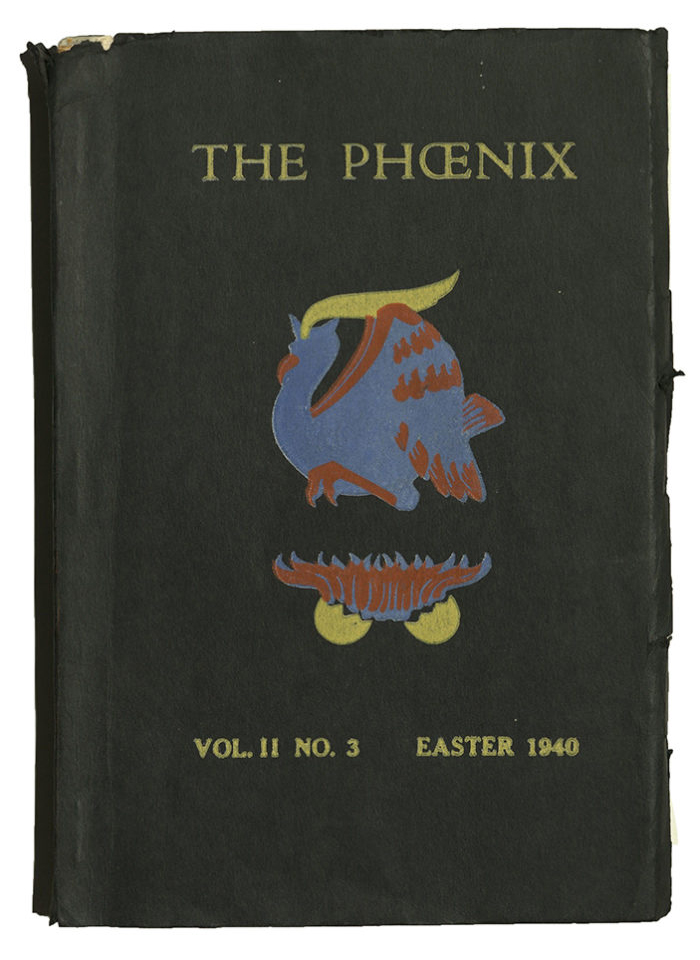

Blanche and James Cooney had a goal: to forge a community of self-sufficient artists and intellectuals dedicated to the political philosophy of pacifism. In upstate New York, they found their first glimpse of hope on a blossoming art commune owned by Hervey White. White had bought the property outside of Woodstock in 1905, and by the time the Cooney’s arrived, the farm — or “The Maverick” as it was called — was already a well-known intellectual meeting place with minimalistic houses and music halls. Very quickly, the Cooney’s developed their own niche in the community. With White’s hand press and type, Blanche and James started a printing press in order to produce a pacifist journal. Just like that, The Phoenix was born.

The title of the quarterly was inspired by D. H. Lawrence and his poem “Phoenix.” James believed that Lawrence was the man to turn to in the times of peril, for although he is dead, “his words are not dead. His word are most vividly, magically alive, gleaming in the darkness of our tomb like stars by which to chart our course.” Lawrence had adapted the emblem of the phoenix and used it in many of his publications. For their own phoenix design — which features prominently on every cover — The Cooneys employed yet another Maverick resident, artist Tom Penning. For the first issue, a call for submissions went out in a New York paper and, before long, The Phoenix became “a rallying point for emigres from a world gone mad.” One of the first writers to show interest was Henry Miller.

In exchange to have his banned works published, Miller vowed to introduce Cooney to his “staunch and stalwart friends;” those who were rich and influential: editors, publishers, critics; as well as lists of possible subscribers. His friends included essayist and writer of erotica, Anaïs Nin, and Miller’s “patron of the arts” in Paris, Michael Fraenkel. So pleased with the first issue of The Phoenix, Fraenkel wrote to James, “Sending copies to Jung, Keyserling, Brill and others interested in my work, so you see the magazine will be going to important people in many countries —.” The Phoenix and Maverick Press became the first American publisher for Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin, and with their contacts it reached international fame. Other contributors included Kay Boyle, Jean Giono, Robert Duncan, Rayner Heppenstall, Thomas McGrath, J.C. Crews, and William Everson.

Eight issues were published between 1938 and 1940, with the first two volumes entirely handset and printed by the Cooneys and their volunteers in Woodstock. However, with the onslaught of World War II and France’s fall to the Third Reich, the pacifist quarterly entered a long period of silence. The press was put on hold for thirty years, during which the Cooneys had expanded their family and moved to a farm in West Whately, Massachusetts. Disillusioned once again with war — this time, Vietnam — James Cooney picked up where he left off and The Phoenix was resurrected in a new print shop: the Morning Star Press.

The last few years of The Phoenix were difficult. In 1981, James had suffered a stroke that left him crippled with aphasia, which Blanche had called “cruel punishment for a man whose tongue was so fluent, so outrageous, to be suddenly silenced.” It was a slow recovery to health, but his passion allowed him to produce three more volumes before the publication eventually went under. Volume 8 (1980/82) was comprised entirely of letters Henry Miller had written to the Cooneys during the formative years of The Phoenix. The last volume (1983/84) was simply a “trophy of Jimmy’s tenacity.”

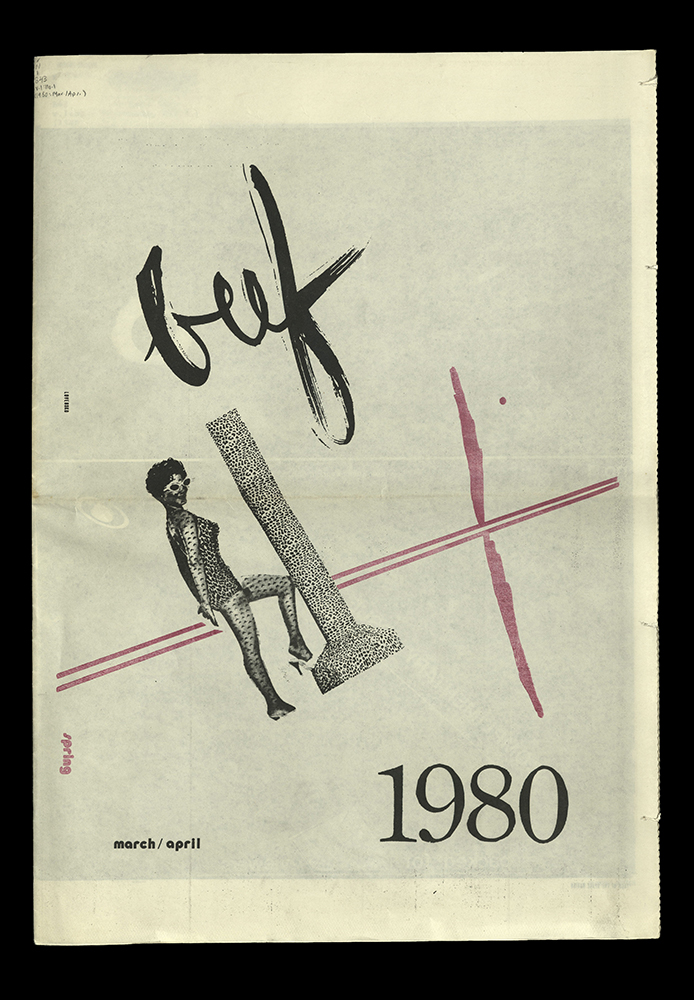

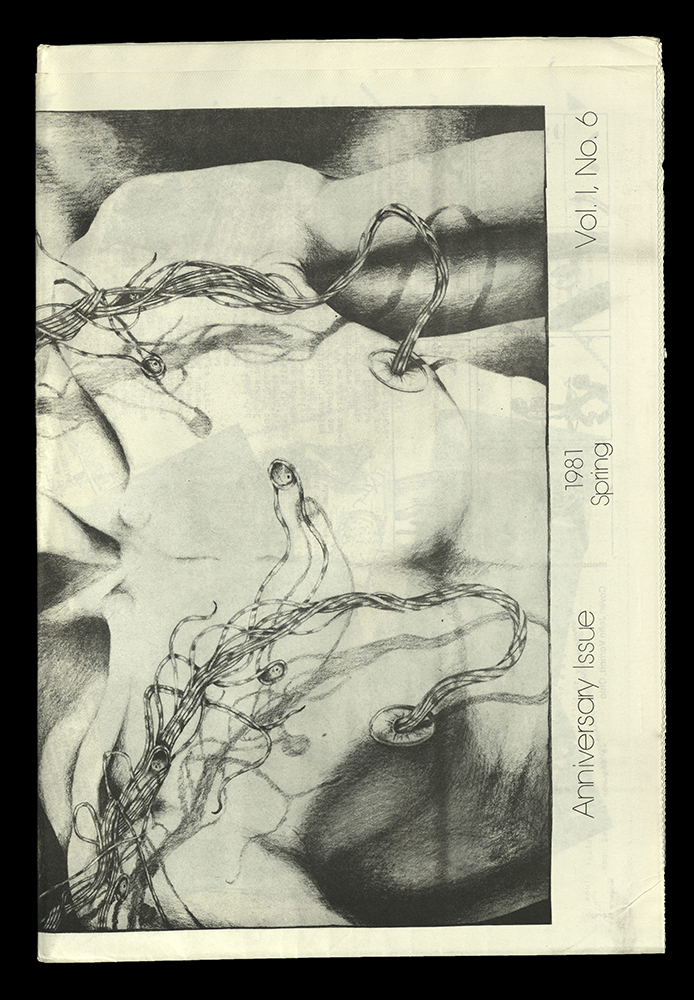

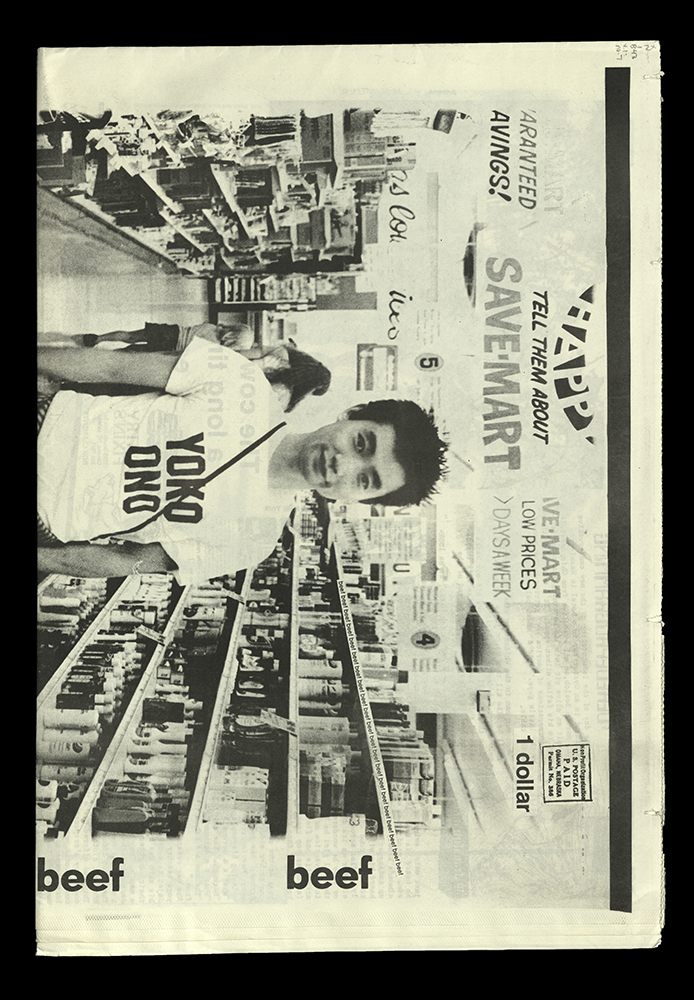

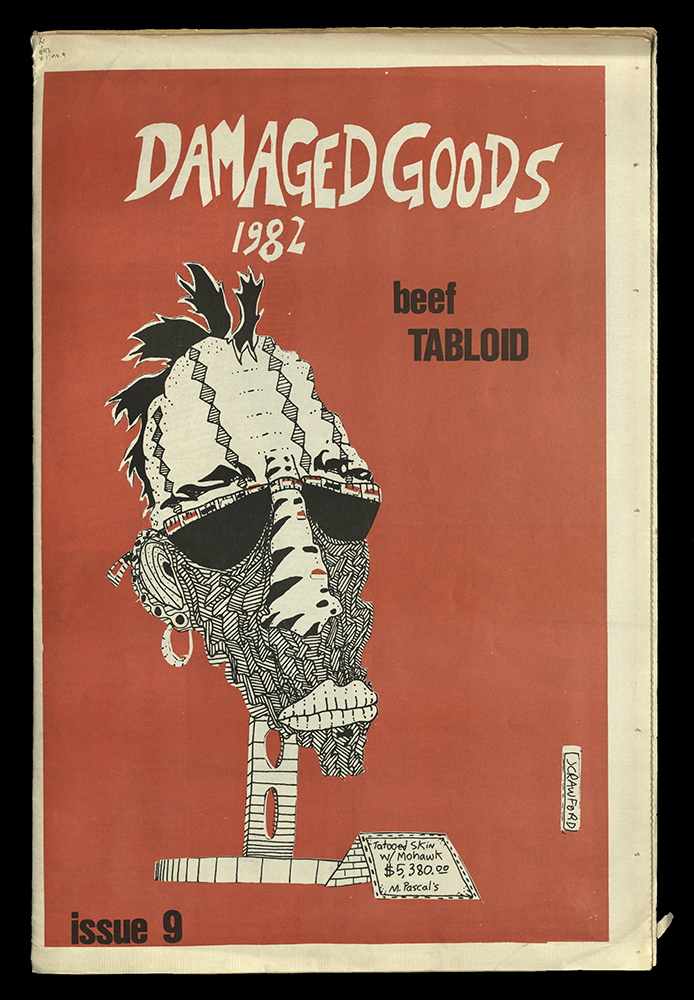

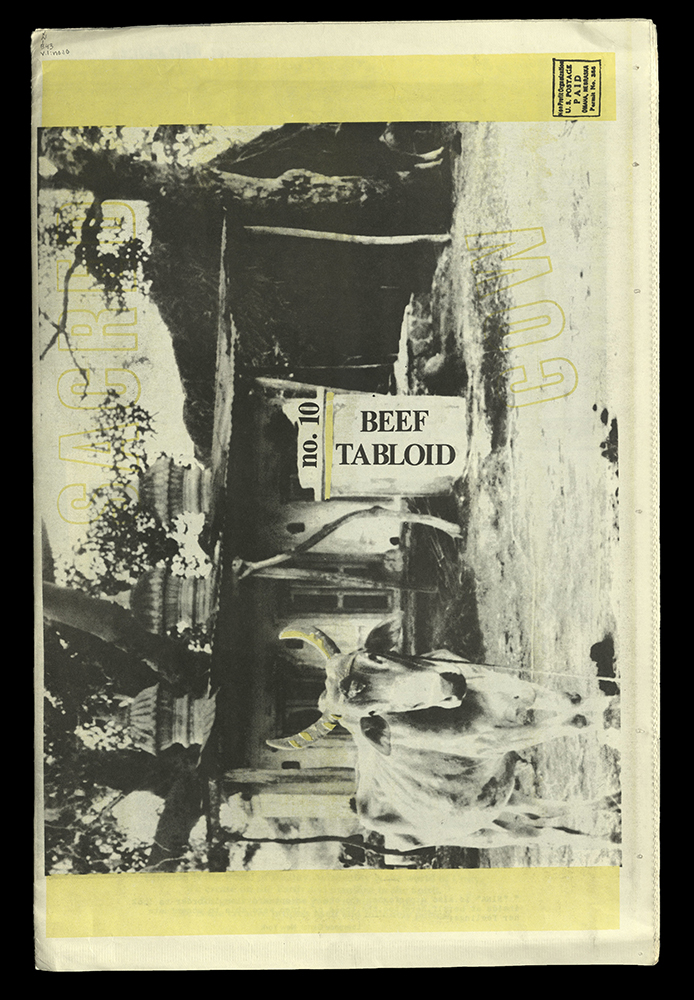

THE PHOENIX

Woodstock, New York: Maverick Press, 1938 - 1984

AP2 P556

From 1938 – 1984 the Phoenix and the Cooneys represented a rare bridge between two of the richest radical movements in American history — the socialist movement of the 1930s and the peace movement of the 1960s. It was a pioneering publication that was willing to put into print material mainstream media would consider countercultural, radical and revolutionary. Eight issues were published between 1938 and 1940, with the first two volumes entirely handset and printed by the Cooneys and their volunteers in Woodstock.

DEBS, HAYWOOD, RUTHENBERG

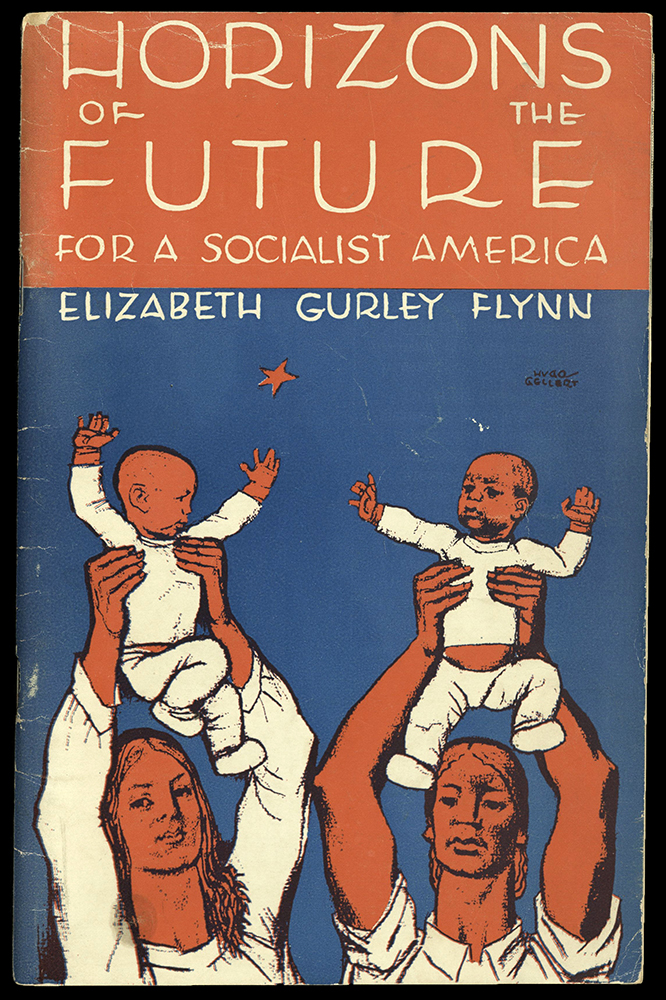

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : Workers Library Publishers, 1939

HX89 F58 1939

Eugene Debs, "Big Bill" Haywood and Charles Ruthenberg were central figures of the Socialist Party of America during the 1930s. This pamphlet, written by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and published by the Workers Library Publishers, celebrates their victories in the early years of the twentieth century. Although all three men had passed away during the previous decade, their legacies continued to live on in print.

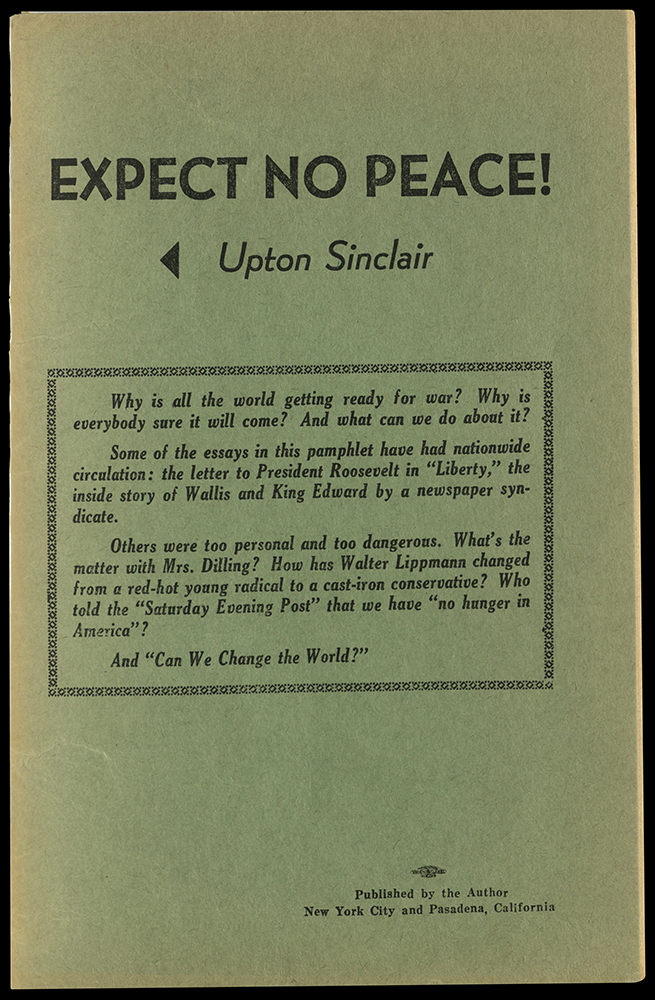

EXPECT NO PEACE!

Upton Sinclair (1878 – 1968)

Girard, KS : Haldeman-Julius Publications, 1939

HX86 S614 1939

In 1904, Upton Sinclair spent seven weeks in disguise, working undercover in Chicago’s meatpacking plants in order to do research for a political expose that would address the dangerous working conditions, as well as the lives of immigrant workers. What would later be published as Sinclair’s seminal work, The Jungle was initially published in serial form in the Socialist newspaper, Appeal to Reason, from February 25 to November 4, 1905.

Publication of Appeal to Reason was located in the small town of Girard, the center of coal-mining in Kansas. After founder, Julius Augustus Wayland, died by suicide in 1912, the newspaper was sold to Marcet and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius. Building on the subscriber list of Appeal, Haldeman-Julius developed the lucrative publication of Little Blue Books. Though the renamed Haldeman-Julius Weekly had lost its explicit socialist character, Sinclair remained in contact with the publishers, who printed several of his political pamphlets including Expect No Peace! and What Can Be Done About America’s Economic Troubles?

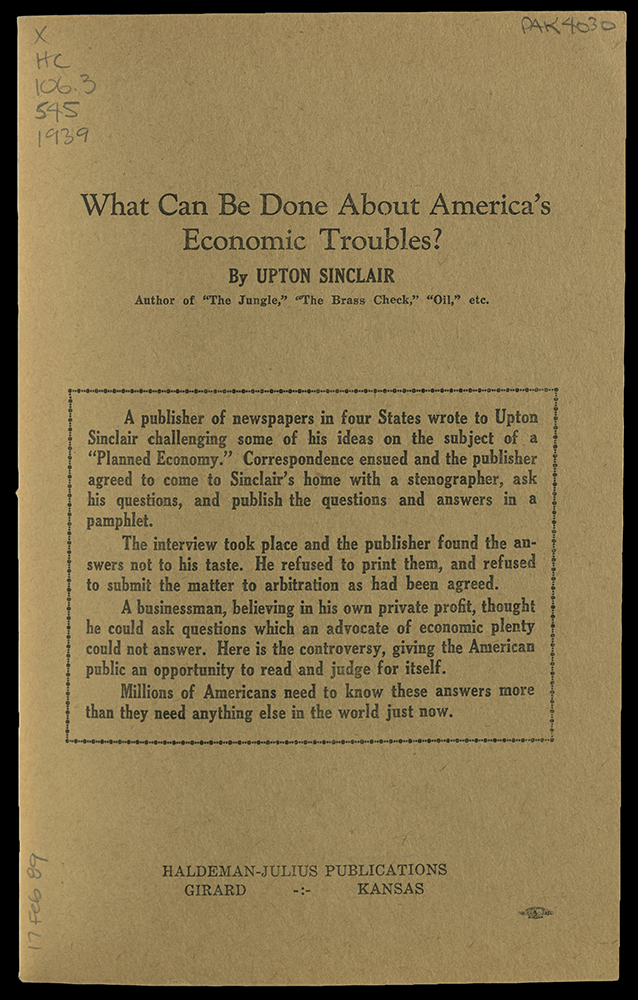

WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT AMERICA'S ECONOMIC TROUBLES?

Upton Sinclair (1878 – 1968)

Girard, KS : Haldeman-Julius Publications, 1939

HC106.3 S45 1939

A conversation between newspaper publisher Raymond C. Hoiles and writer Upton Sinclair regarding planned economy. Hoiles was an American newspaper publisher during the twentieth century, becoming president of Freedom Newspapers in 1950, a chain of newspapers located around Los Angeles, Riverside and Orange County. He held this position his death in 1970. Hoiles was a self-described “voluntaryist,” holding the view that all forms of human association should be voluntary. One of his most passionate and controversial positions was regarding the separation of education system and the State. Another position which he argued against was taxation of American people to support government programs such as welfare, stating, “It too thousands and thousands of years to understand the folly of chattel slavery and it is going to take quite a spell to get people to understand that it is just as disastrous, in the long run, to be the slave of all-powerful government.”

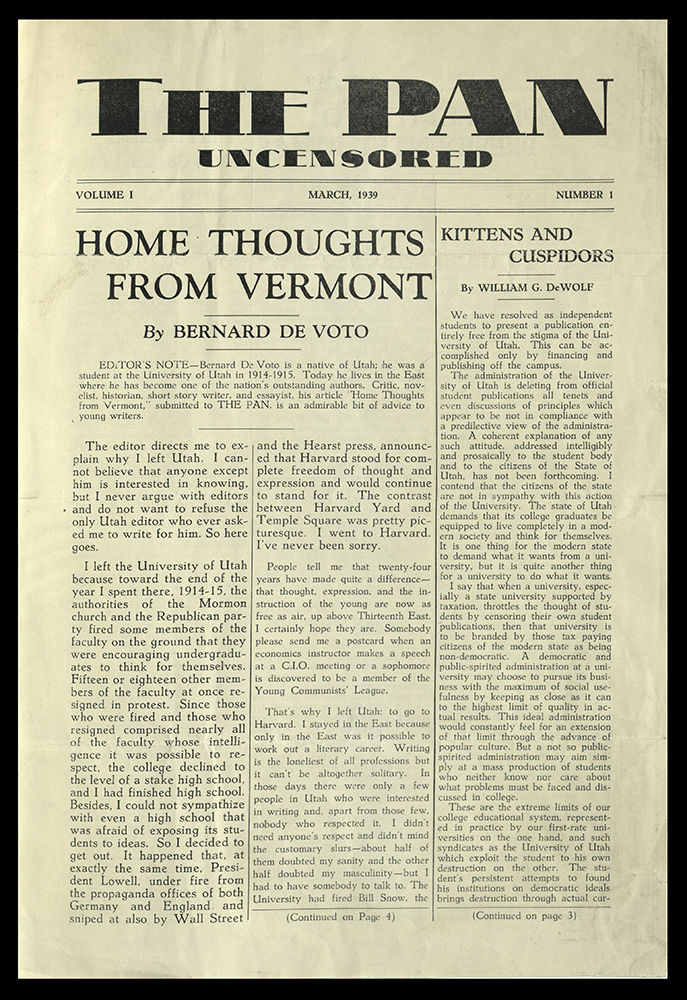

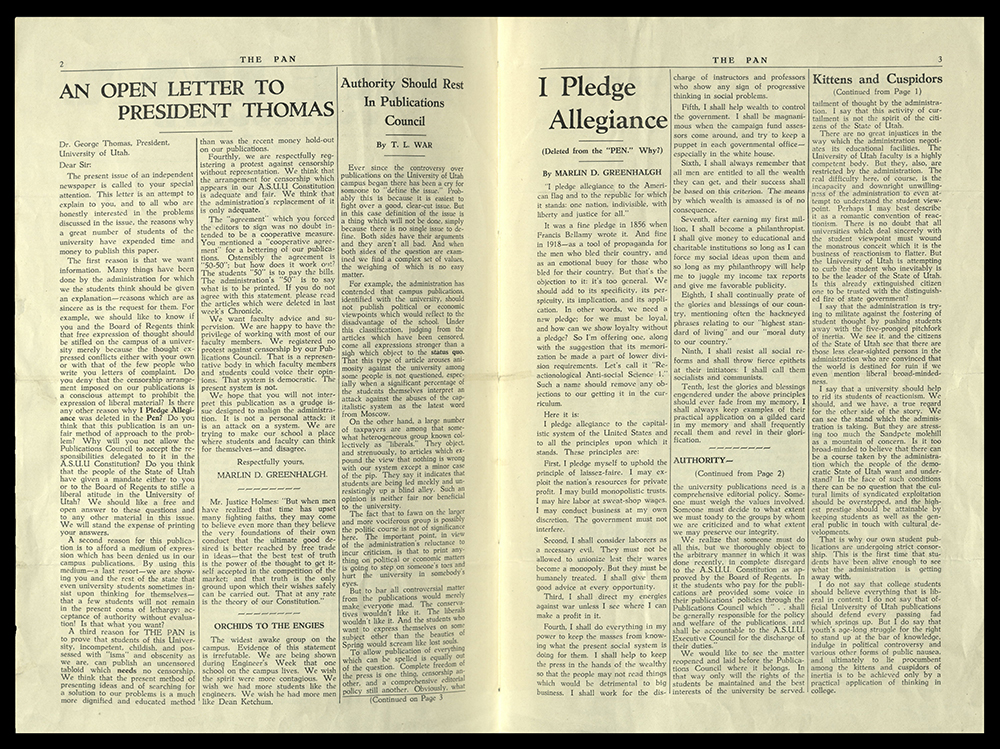

THE PAN UNCENSORED

Salt Lake City, UT : 1939 -

LH1 U8 P3

An off-campus publication established in response to censorship challenges students faced at the University of Utah. Several articles pertaining to previous rejections in the University’s official publication, Pen. Volume 1, number one includes an essay by Bernard DeVoto on why he left the University of Utah; an open letter to the University President, George Thomas, and the rejected op-ed, titled, “I Pledge Allegiance” by Marlin D. Greenhalgh.

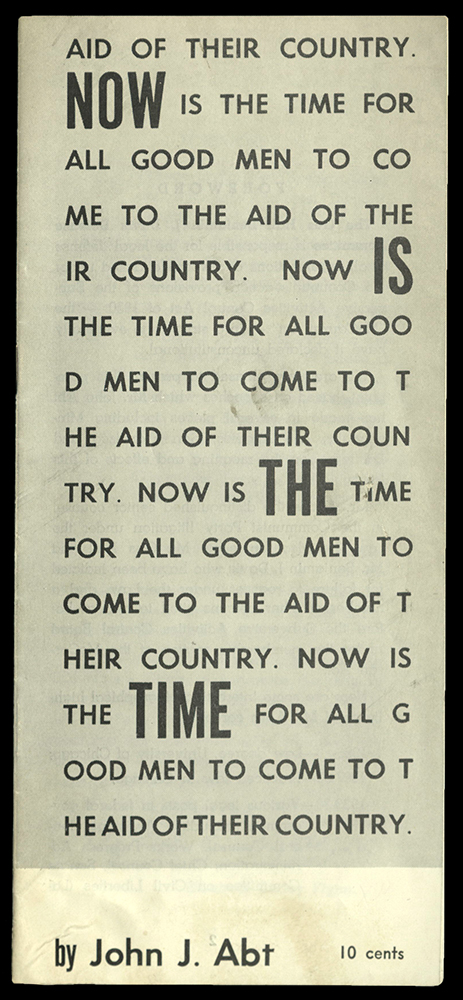

THE SMITH ACT

Following the Congressional investigation of both left-wing and right-wing extremist political groups in the mid-1930s, support grew for a statutory prohibition of their activities. On June 28, 1940 Congress passed the Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, after its principal author, Rep. Howard W. Smith (D-VA). The Smith Act required all non-citizen adult to register with the federal government, and criminalized any “intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any such government, prints, publishes, edits, issues, circulates, sells, distributes, or publicly displays any written or printed matter advocating, advising, or teaching the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or attempts to do so; or...organizes or helps or attempts to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any such government by force or violence; or becomes or is a member of, or affiliates with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof.” Prosecutions under the Smith Act continued from 1940 to 1957, with more than two hundred people indicted under the legislation, including alleged communists, anarchists, and fascists. In 1957, however, a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions reversed a number of convictions under the Act as unconstitutional. Although the law has been amended several times throughout modern history, it has never been officially repealed.

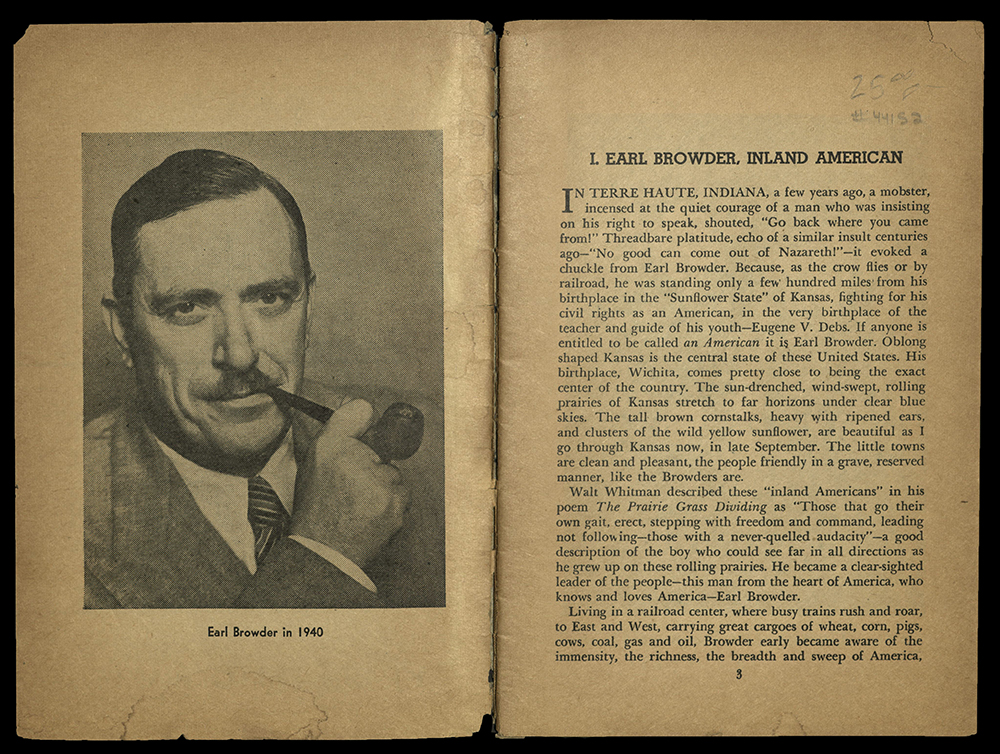

EARL BROWDER : THE MAN FROM KANSAS

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : Workers Library Publishers, 1941

HX84 B7 F6 1941

Earl Browder was an American political activist and General Secretary of Communist Party USA (CPUSA) during 1930s and 1940s. He was associated with socialist and syndicate groups during the early twentieth century, and aggressively opposed United States involvement in the first World War. Due to his outspoken nature and controversial politics, Browder was investigated by the U.S. Department of Justice and subpoenaed to appear before the House Special Committee on Un-American Activities. During his testimony, Browder admitted to having traveled abroad under a false passport and was subsequently indicted for passport fraud, a felony. On January 17, 1940, Browder’s trial began. The conviction carried a maximum sentence of ten years in prison and a $4,000 fine. On March 25 the following year, Browder was transported to the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary and sentenced to four years.

This pamphlet, written by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and published by the Worker’s Library Publishers, was part of the “Free Earl Browder” campaign, instigated by the Communist Party. According to the Citizens’ Committee to Free Earl Browder, “The Browder case is known to the public only because he is a prominent Communist. Were it not for this fact, the case would probably have gone unnoticed: but on the other hand, except for this fact, the case would never have arisen, and Browder would not now be in Atlanta Penitentiary.”

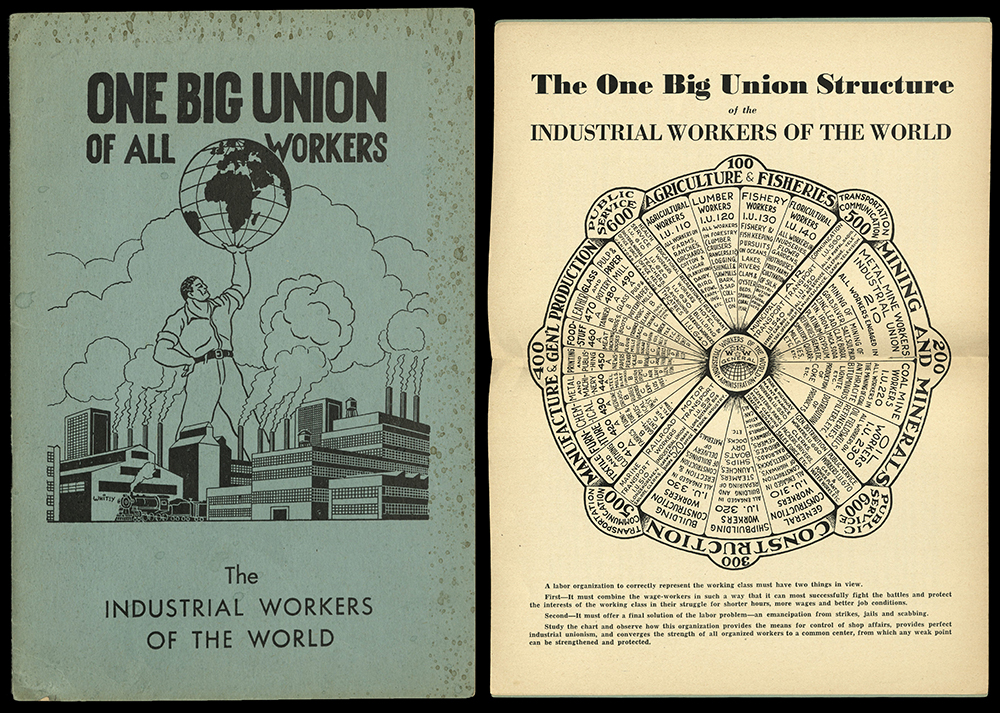

ONE BIG UNION OF THE INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD

Industrial Workers of the World

Chicago, IL : Industrial Workers of the World, 1944

HD8055 I5 O6 1944

"One Big Union" was an idea established by trade unionists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The goal was to unite the interests of workers of all trades in order to fight for solutions to the ongoing labor problems. Initially, unions were organized by craft. However, without centralized organization, the individual craft unions could not generate the numbers or influence to take on the large corporations. By organizing unions along industrial lines, as envisioned by the Industrial Workers of the World, union members could achieve working-class control of big businesses.

In an early One Big Union pamphlet, I.W.W. supporters Thomas J. Hagerty and William Trautmann laid out two main goals. First, One Big Union needed to “combine the wage-workers in such a way that it can most successfully fight the battles and protect the interest of the workers of today in their struggles for fewer hours of toil, more wages and better conditions.” Second, One Big Union “must offer a final solution of the labor problem – an emancipation from strikes, injunctions, bull-pens, and scabbing of one against the other.”

THE UNTIDE PRESS

Between 1941 and 1946, a press set up by a group of conscientious objectors held in a Civilian Public Service camp in Waldport, Oregon during World War II published nine books of poetry from four separate authors. In that group of conscientious objectors was William Everson, or Brother Antoninus as he was later called. Although Everson did go on to gain recognition among other poets during the San Francisco Renaissance, limited scholarship has been done about the other authors in Waldport or the press itself. Perhaps this has to do with the authors’ status as conscientious objectors and the ephemeral qualities of their published works: books made from cheap paper that were unlikely to last. The press had lasted only five years, and the limited runs that were printed had been lost among the conscientious objector's camps across the country, soon to be forgotten. Yet, the existence of the COs and their publications reemerges with these books, a material memory which allows us to recall the history not only of the Untide Press, but also of conscription in the United States during World War II, along with the influence of anti-war poetry on twentieth-century American literature. The rareness of these books was thus determined by their printers – the conscientious objectors held in special labor camps for the duration of the war to do “work of national importance” in lieu of being sent overseas. Not only were these books printed in limited editions, but they were printed under the most exceptional circumstances.

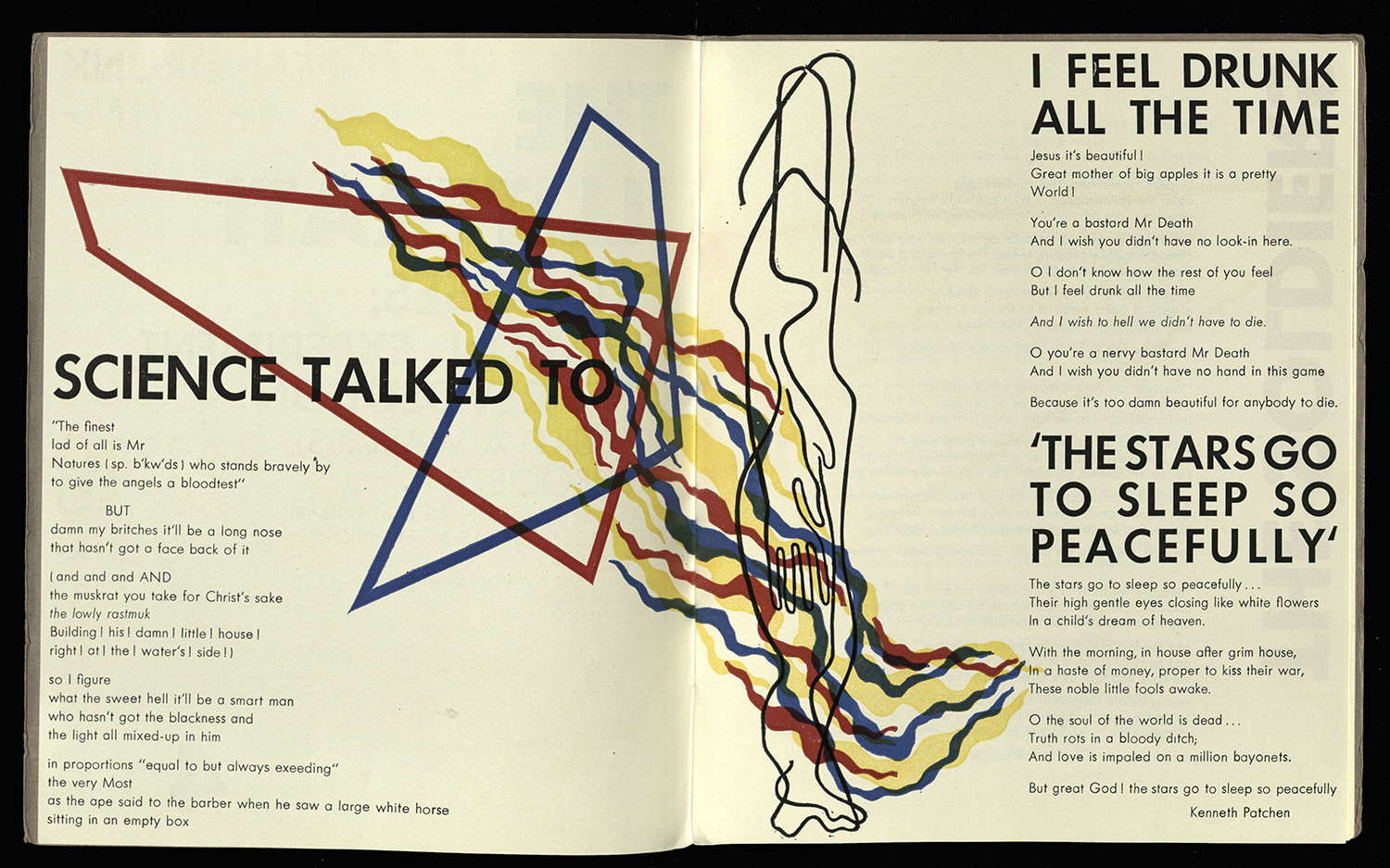

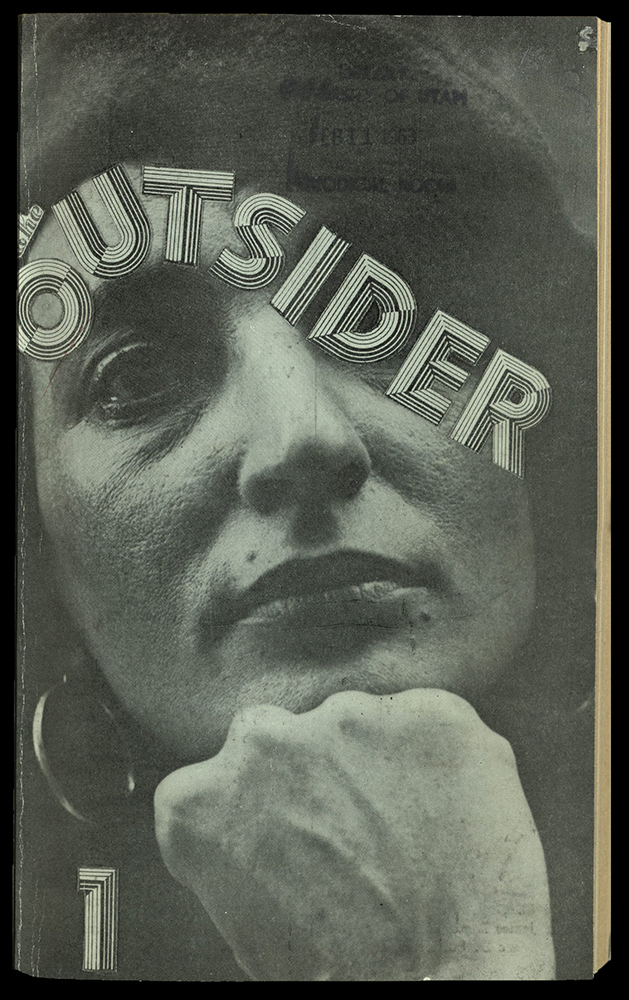

THE ILLITERATI

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1943 – 1945

PS1 I55 no. 4

Based on the meticulous work of the Untide Press, the platform for the conscientious objector's voice was not only being recognized within the CPS camps, but also in literary circles across the country. Outside the camp, literary journals such as Partisan Review, Pacifica Views, and Twice a Year were catching on and praising the Untide Press and its offspring, The Illiterati, which had been publishing excerpts from notable writers such as Henry Miller and Kenneth Patchen. Despite being published on an erratic schedule, The Illiterati extended an invitation of revolution and incorporated the works of artists and writers who were not confined in Oregon but who, nonetheless, remained dissidents against the war. Both Miller and Patchen contributed to the fourth issue, printed in the summer of 1945. On its initial page, the journal proposes “creation, experiment, and revolution to build a warless, free society.” Unlike the works previously mentioned, this issue has glossy pages that suggest a more commercial production, like that of a magazine. Although some similarities are present, the use of color and illustration was far more unrestrained than in the other works published by the Untide Press.

Edited by Kemper Nomland and Kermit Sheets. “Poems, stories, musical compositions, informal sketches written by Pacifists conscripted to do work of national importance.” Illiterati issues 1 and 2 produced at Cascade Locks, both mimeographed; no. 3 at Cascade Locks and Waldport, combination mimeographed and letterpress; no. 4 at Waldport; nos. 5 and 6 at Pasadena (all done by letterpress). Circulation unknown. Issue 1 is considered to be extremely rare after the U.S. Post Office destroyed an unknown number of copies, due to drawing of a nude female considered “of an obscene, lewd, lascivious and indecent character.”

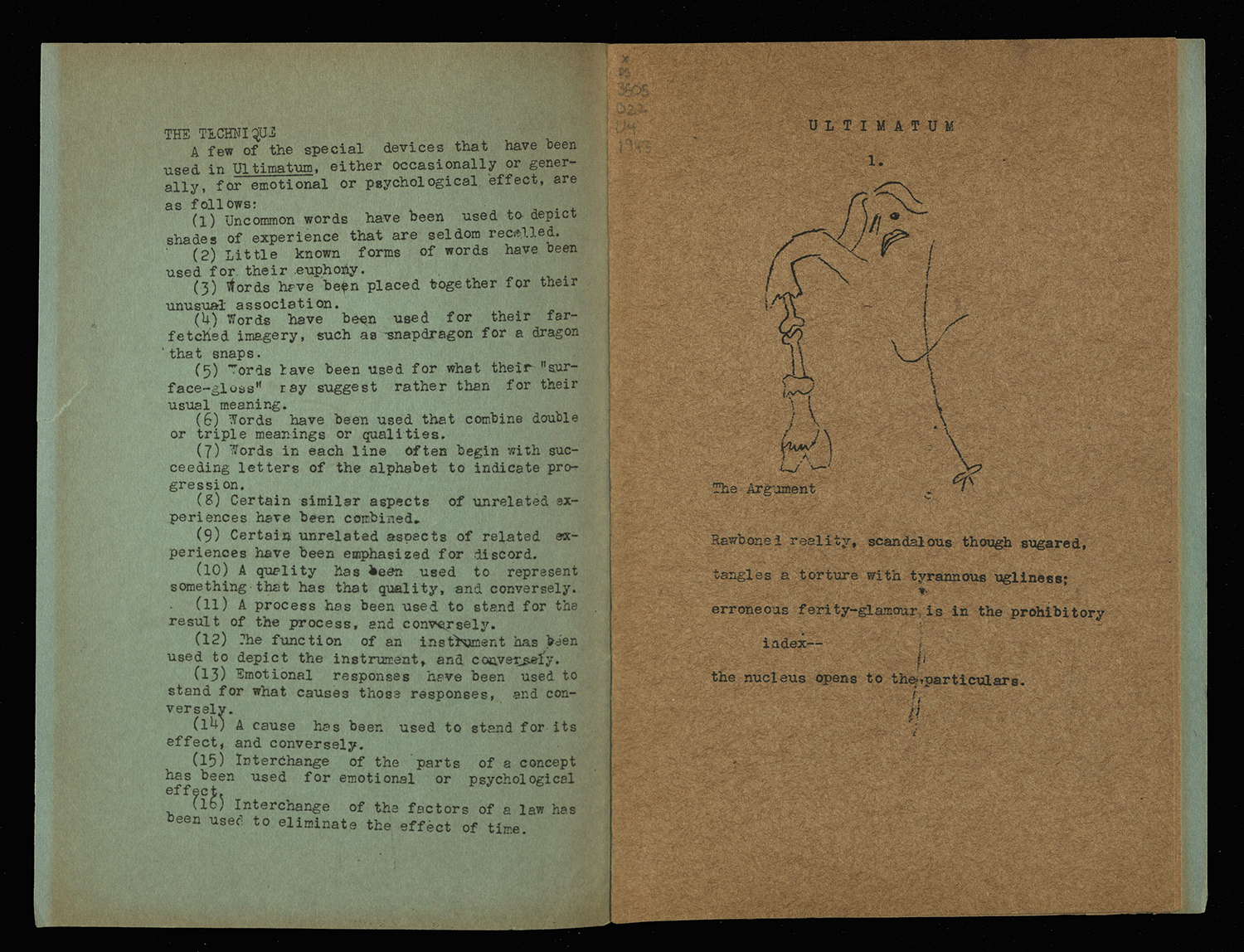

ULTIMATUM

Glen Coffield (1917 – 1981)

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1943

PS3505 O22 U4 1943

Glen Coffield was a self-proclaimed anarchist from Missouri who was known write dozens of poems a day. After being drafted for the war, Coffield walked nearly three hundred miles from his home in Missouri to CO Camp #7, in Magnolia, Arkansas. He did so as a form of protest, unwilling to accept the bus transportation provided by the government. Ultimatum was produced entirely by Coffield – the writing, illustrating, stencil-cutting, mimeograph-cranking, and stapling. Inside the construction paper cover, blemishes on the page resemble ink stains left from the rudimentary mimeograph machine. It is believed that only fifty copies were produced, and it is unknown whether those were sold or given away.

THE HORNED MOON

Glen Coffield (1917 – 1981)

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1944

PS3505 O22 H6 1944

The second collection of poems by Glenn Coffield and the Untide Press was titled The Horned Moon. Printed in 1944 with the collaborative efforts of Coffield as author, and William Everson and Charles Davis acting in design. In addition, other members of the Waldport Fine Arts Group put in their spare time to help with printing, folding, and sewing. Unlike Coffield’s Ultimatum, this work was far less experimental and lacked the imagery featured in the first. Single signature pamphlet, hand-sewn, with folded wrapper cover. Issued in February 1944. 500 copies printed, although the colophon states 600, on India Mountie Eggshell Book paper. Text pages done on a Kelsey Excelsior hand-operated press, while wrapper paper printed on a Challenge Gordon press at Waldport, Oregon. Unknown number of copies sent out as gifts to subscribers of the Illiterati with mimeographed announcement laid in. Sold for 25 cents.

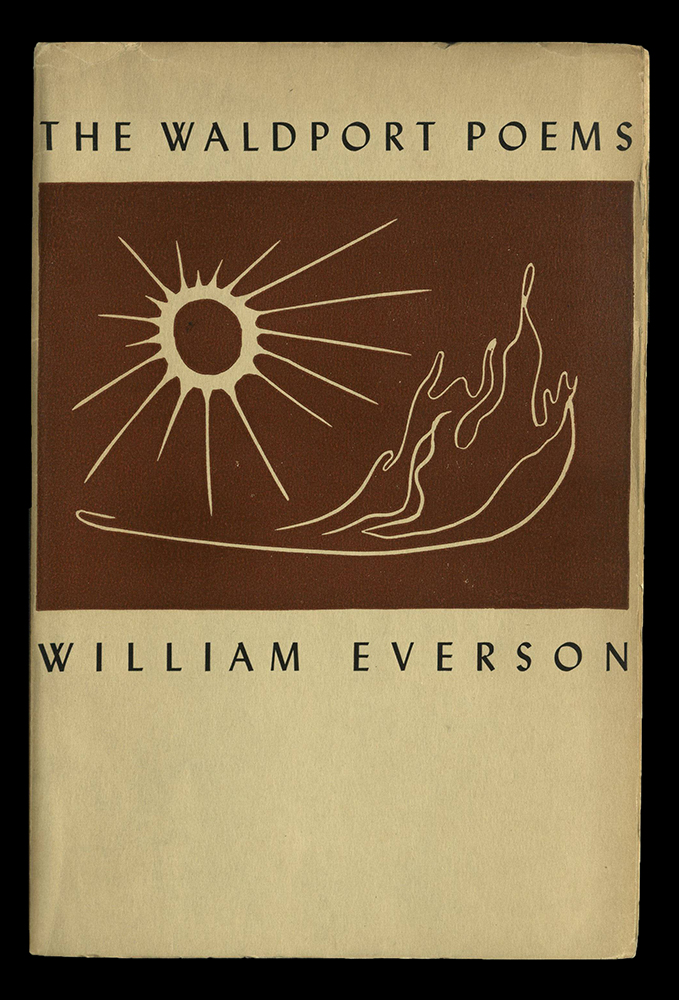

THE WALDPORT POEMS

William Everson (1912 – 1994)

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1944

PS3509 V65 W3 1944

From the author's prefatory note: "This series of poems is an attempt to render whole the emotional implications of a kind of life that has become almost universal: the life of the camp, the life of enforced confinement, individual repression, sexual segregation. Everywhere in the world these centers exist, huge impermanent cities housing millions of men - conscription camps, concentration camps, prison camps, internment camps, labor camps. Their effect upon the human spirit is not to be measured within the framework of a generation; the scars will remain for decades." Poetry by William Everson. Linoleum block illustrations by Clayton James, who also designed the book in consultation with Everson. Total edition of 975 copies, with 400 copies handsewn. Single printing on Ivory Linweave Text Antique laid paper on a Challenge Gordon press, at Waldport. Sold for 25 cents. Rare Books copy gift of Brewster Ghiselin (1903-2002).

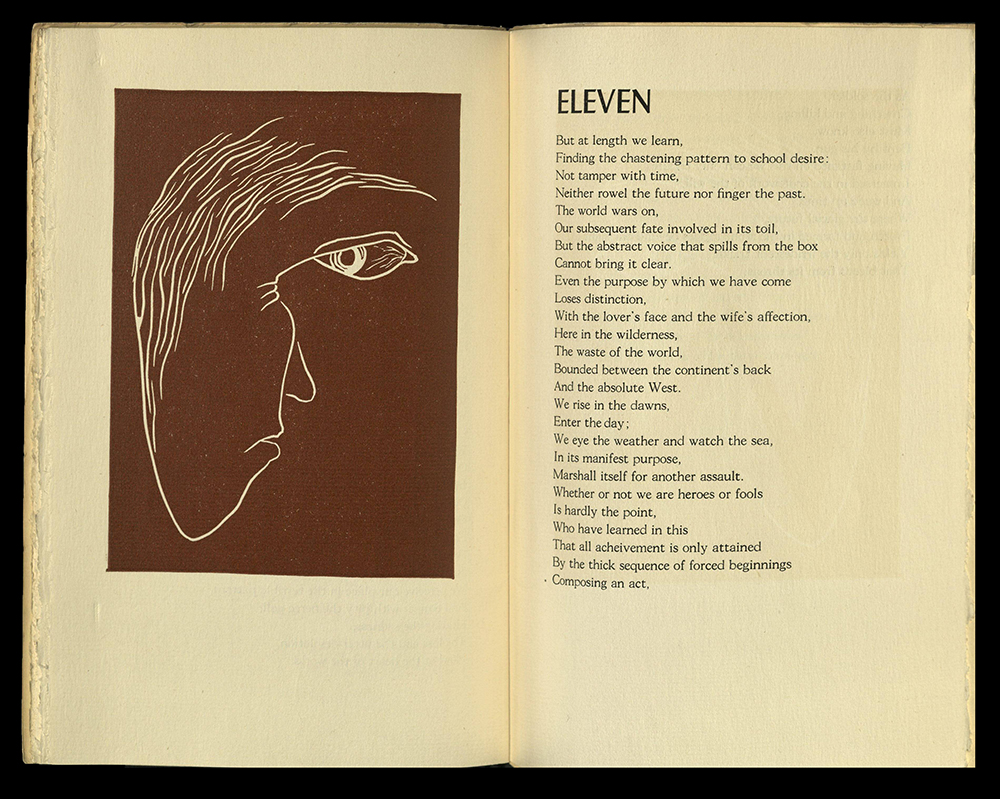

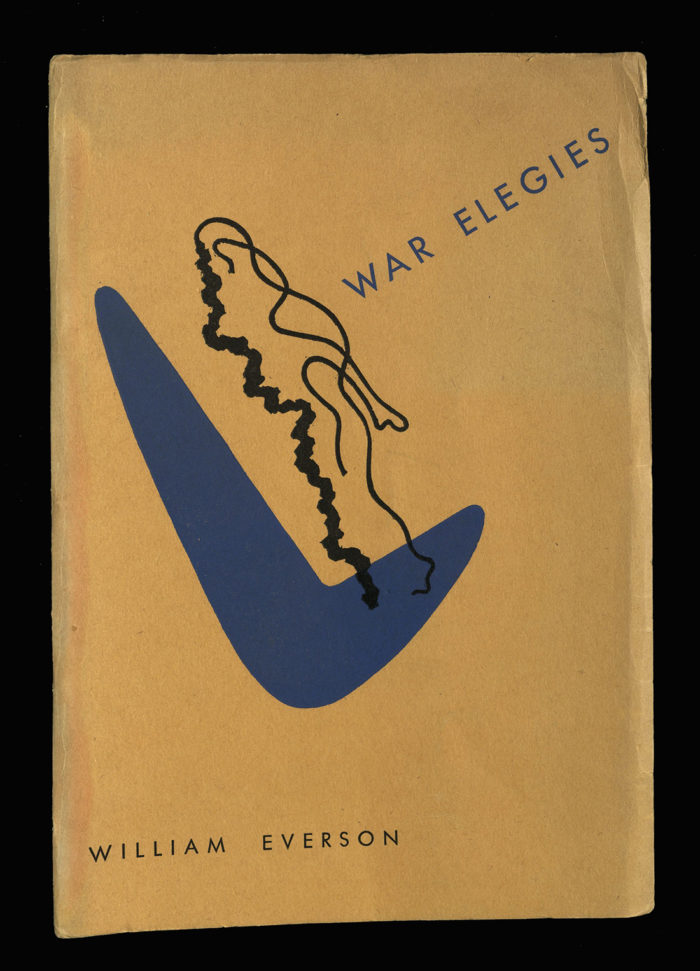

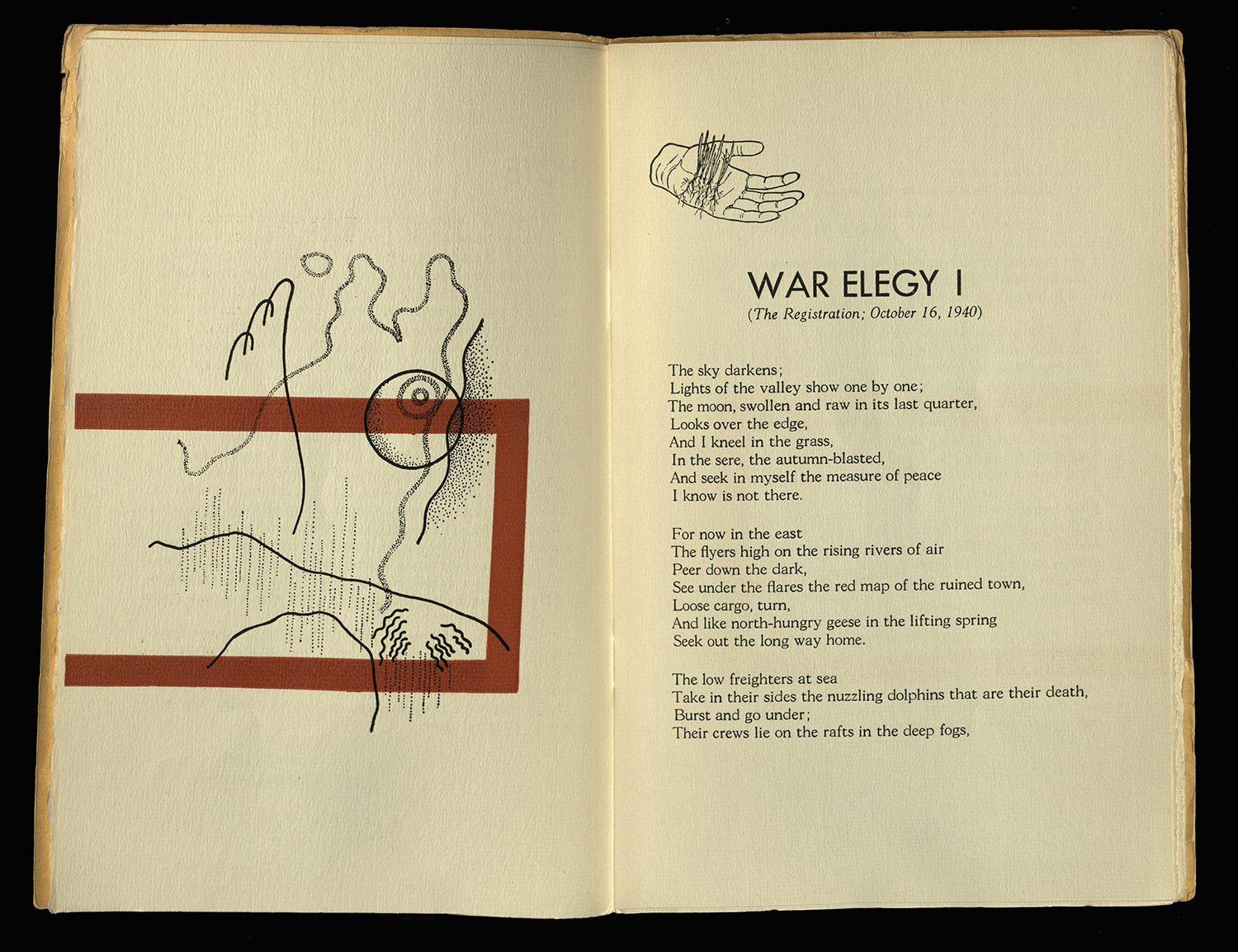

WAR ELEGIES

William Everson (1912 – 1994)

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1944

PS3501 N77 W35 1944

Poetry by William Everson. Illustrated by Kemper Nomland, Jr. (1919-2009). From the poet’s note: “…the first ten were written between 1940 and 1942 at my home in Selma, California. The eleventh was written early in 1943 shortly after my induction into a camp for conscientious objectors here on the Oregon coast.” From the colophon: “…presented in its first printed form. It was previously issued by mimeograph in 1943 as the initial publication of Untide Press. The present printing contains in addition War Elegy V.” Hand-set in Goudy Light Oldstyle and Futura types. Printed in red and black on Linweave Early American. In orange wrappers printed in blue and black. Single printing of 982 copies, although colophon states an edition of 975, thirty of which are signed. Printed in December 1944 on a Challenge Gordon press.

Kemper Nomland was an architect who worked out of Los Angeles, California. He was partner with his father Kemper Nomland, Sr. Kemper Jr. was also a painter and printer. As a conscientious objector during World War II, he served at a camp in Cascade Locks, Oregon, where he worked on a forest maintenance team. He also lived in Camp Angel, near Waldport, Oregon, where he was involved with the Untide Press as a book cover designer and illustrator for Untide Press.

Rare Books copy gift of Brewster Ghiselin (1903-2002).

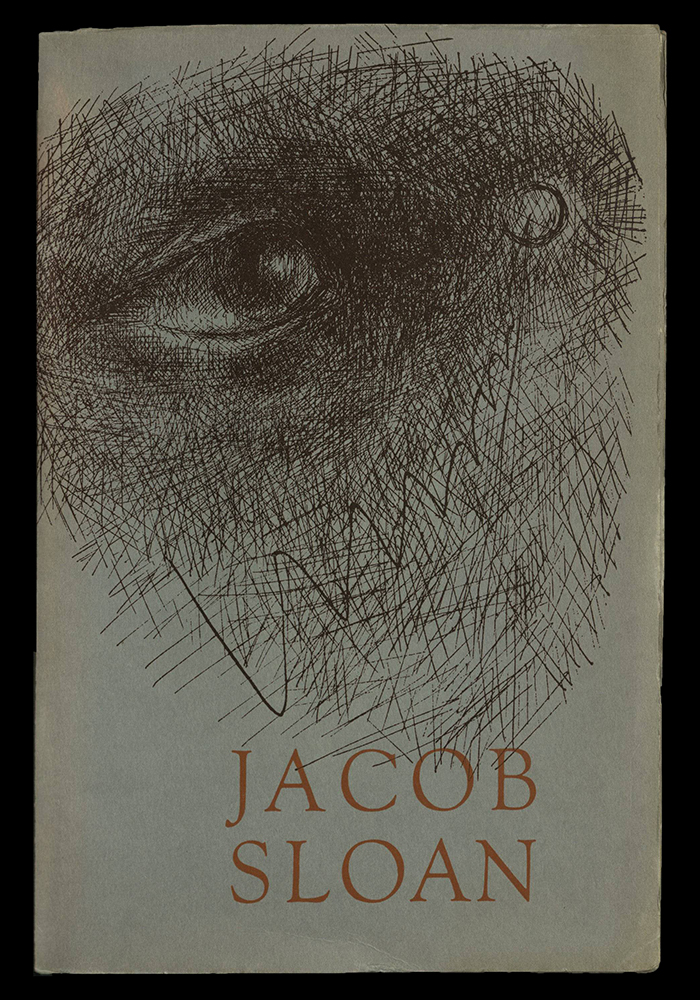

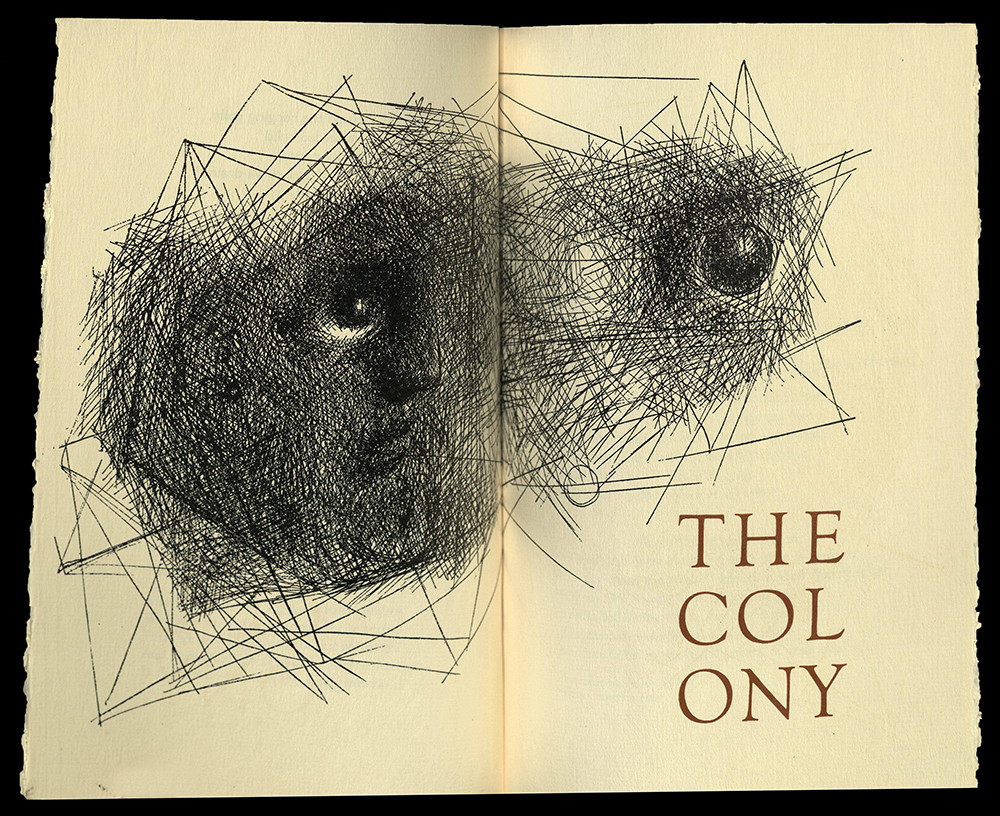

GENERATION OF A JOURNEY

Jacob Sloan

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1945

PS3537 L54 G4 1945

From the colophon: "Generation of a Journey contains the reactions of an American conscientious objector to life in Civilian Public Service camps in New Hampshire and Maryland, and to an interval as an attendant at a state colony for the feeble-minded." Poetry by Jacob Sloan. Illustrated and designed by Barbara Straker James, wife of conscientious objector, Clayton James. Single printing of 850 copies (colophon states 950) on Ivory Linweave Text paper, Antique Grey Hammermill cover. Printed in March 1945 on a Challenge Gordon Press at Waldport. Typographical error in “Walterville Valley” in less than 100 copies; typo in last line of “Waiting En Route” in entire run. Sold for twenty-five cents.

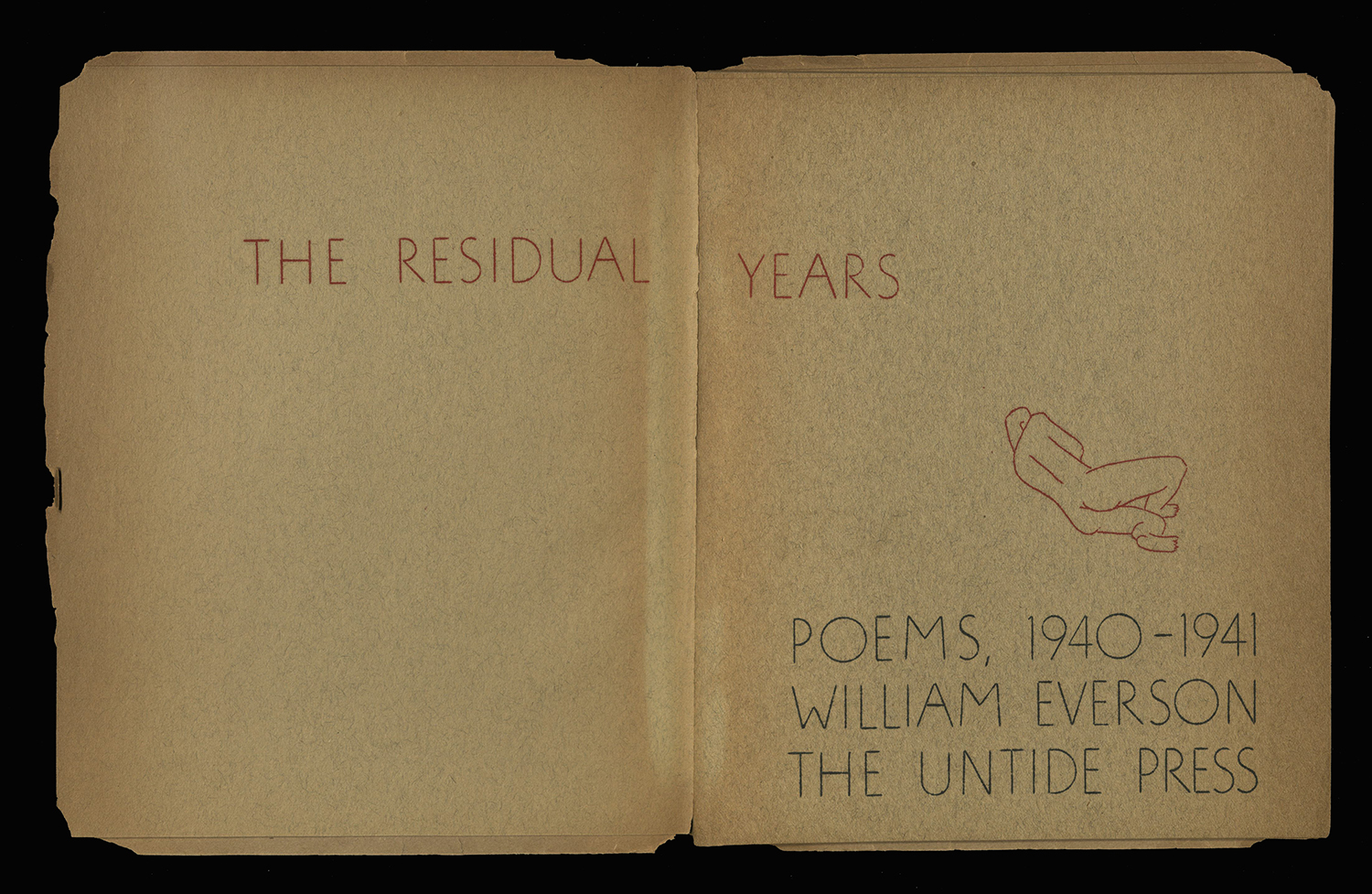

THE RESIDUAL YEARS : POEMS, 1940-1941

William Everson (1912 – 1994)

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1944

PS3509 V65 1944

Poetry William Everson. Designed by David Jackson and William Eshelman in conjunction with the author. Single signature, hand-sewn pamphlet, cover of gray construction paper glued at spine. Mimeographed pages, edition of 330 copies signed by the author with hand-corrected error on page five. Some unsigned copies extant. Released in April 1945 from Waldport. Sold for 15 cents. Rare Books copy signed by author.

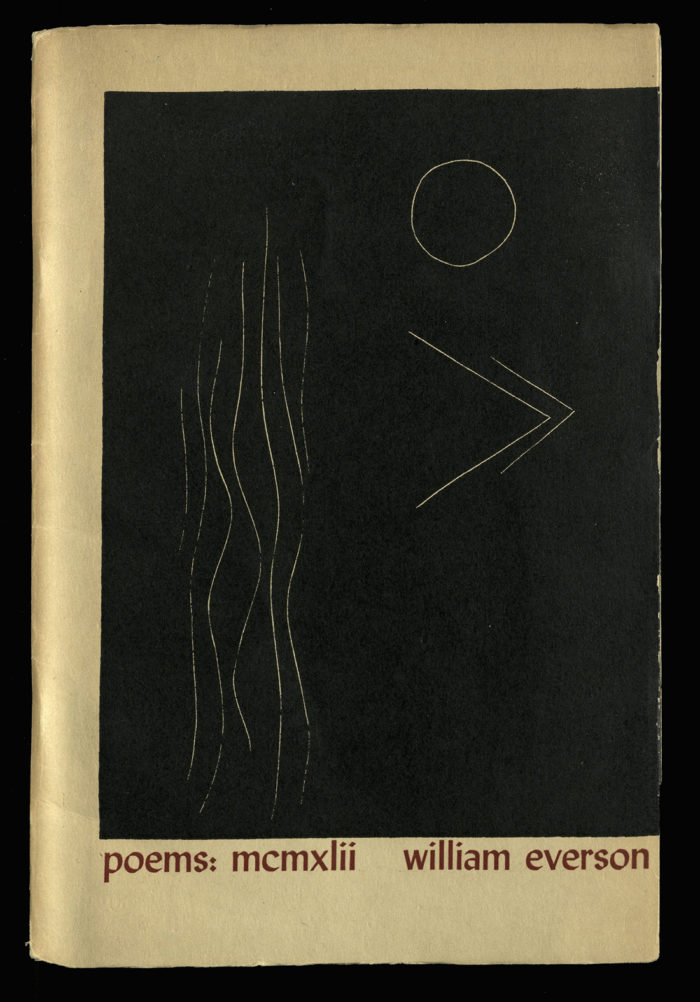

POEMS, MCMXLIII

William Everson (1912 – 1994)

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1945

PS3509 V65 P5625 1945

The printing of Poems was worked on "from time to time between the regular publications of the [Untide] Press, a practice resulting in the blemishes of hast, so that the venerable adage has come home to roost on the printer's head, a disquieting reminder." Poetry by William Everson. Illustrated by Clayton James, and designed by the author. Single printing of 500 copies on White Mountie Eggshell Book paper, India Antique Atlantic cover. Printed on a Challenge Gordon press at Waldport; released for 1945. Errata slip tipped in, featuring a small linocut made by Clayton James. Intended as gifts distributed by the author. Rare Books copy gift of Brewster Ghiselin (1903-2002).

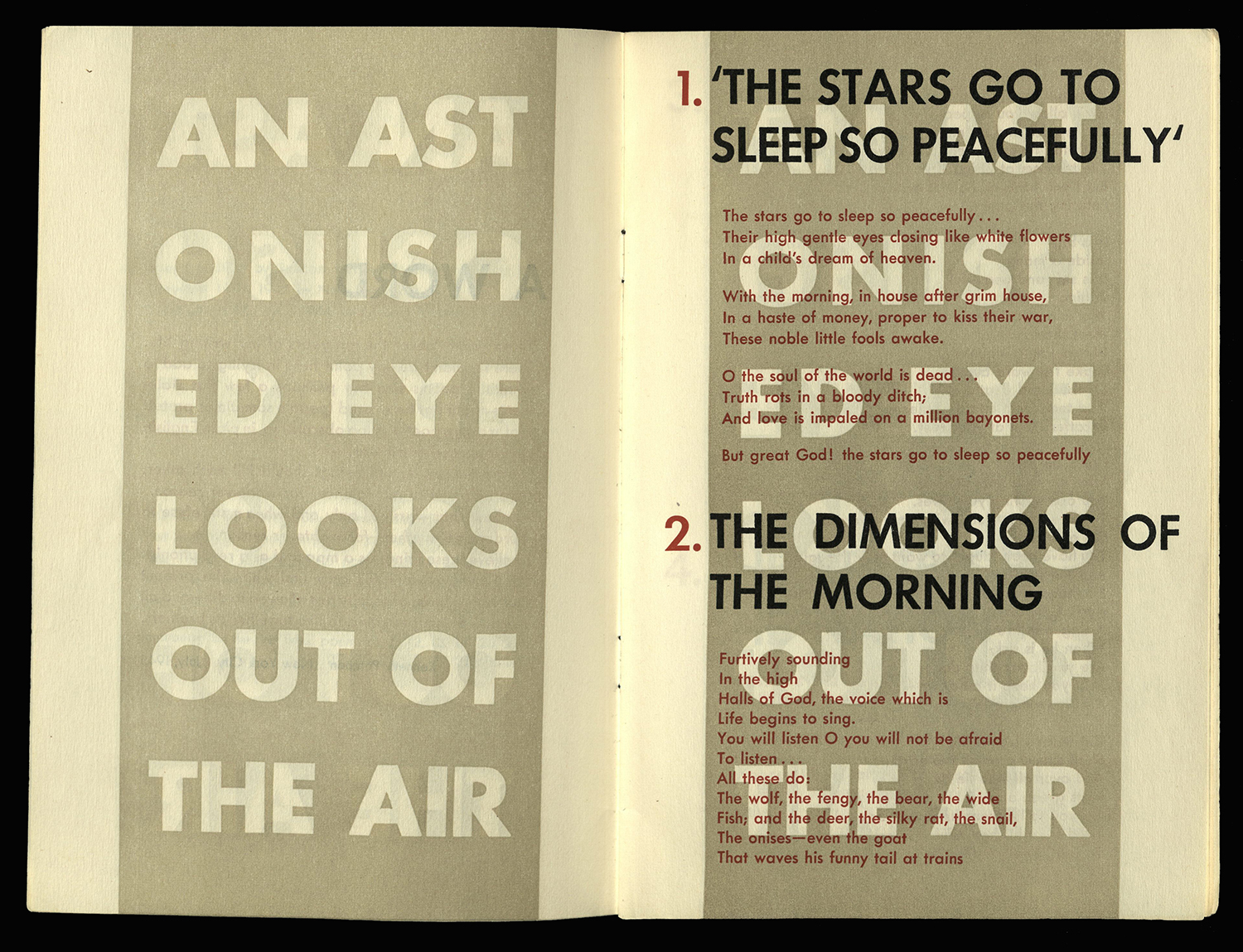

AN ASTONISHED EYE LOOKS OUT OF THE AIR

Kenneth Patchen (1911 – 1972)

Waldport, OR : The Untide Press, 1945

PS3531 A764 A77 1945

Kenneth Patchen was one of the outsiders who contributed his political ideas to the Untide Press and their literary journal, the Illiterati. An acclaimed antiwar poet, Patchen had given Everson and the Untide Press the rights to publish some of his poems in the fourth issue, which later appeared as a complete collection titled, An Astonished Eye Looks out of the Air. This would become the most problematic printing endeavor, and ultimately the most recognized of the Untide Press’s texts. While Patchen was not a conscientious objector himself (having suffered a spinal injury a few years prior to the war that left him physically incapable of serving), he had been corresponding with Everson for some time now and specifically requested Nomland to design the book, based on what he had seen in War Elegies and previous editions of the Illiterati. The production of An Astonished Eye took the crew of Untide Press the remainder of their internment in Waldport, plus an additional five months at another CO camp in Cascade Locks, California, to produce. The book was finally finished and bound in Pasadena, where the Untide Press set up shop after the war. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, co-owner of City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, was so taken by the book's design, he copied it exactly for his Pocket Poets Series, which published Allen Ginsberg's extended poem "Howl" in 1955.

Poetry by Kenneth Patchen. Designed by Kemper Nomland, Jr., whose father trained under Frank Lloyd Wright, from an idea by the author. Gabardine Book paper, Black Antique Albemarle cover. Single printing of 1,950 copies on a Challenge Gordon Press. Author’s signed presentation copy.

"Who are we - the Communists of America?

We are Americans - native born and immigrants; we speak all languages; we are of all religions; of all colors; men and women; young and old. We are miners, steel, railroad, electrical, textile, office workers, trade unionists, farmers, veterans, professionals, housewives, students. We are a cross section of America -folks just like you. Communists are not hermits or highbrows - we like baseball, go to the movies, fish, work in the garden, relish a good Sunday dinner, like nice clothes, enjoy a joke, play with the children - are normal human beings."

MEET THE COMMUNISTS

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : Communist Party USA, 1946

HX83 F55 1946

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was a member of the National Board of the Communist Party, U.S.A., and a veteran leader of the American labor movement. During the 1940s, Flynn traveled to Paris where she attended the International Women’s conference, meeting with many other female activists who played significant roles in resistance movements of Nazi-occupied countries.

In 1946, the Communist Party of the U.S.A (CPUSA) started their Party Building Campaign, with the goal to recruit at least 20,000 new members to the party. The same year, CPUSA published Flynn’s propaganda pamphlet, Meet the Communists, which emphasized the party’s role in combating fascism and capitalism. Though membership was not exactly exclusive, the pamphlet specifically targeted veterans, Black Americans, women, workers, and youth. Flynn described the CPUSA as “a vanguard political party of the working class, to bring together those who are ready not only to fight for day by day immediate gains, both economic and political, but who are also ready to curb and control by nationalization, and eventual to abolish through Socialism, the octopus of monopoly capitalism.”

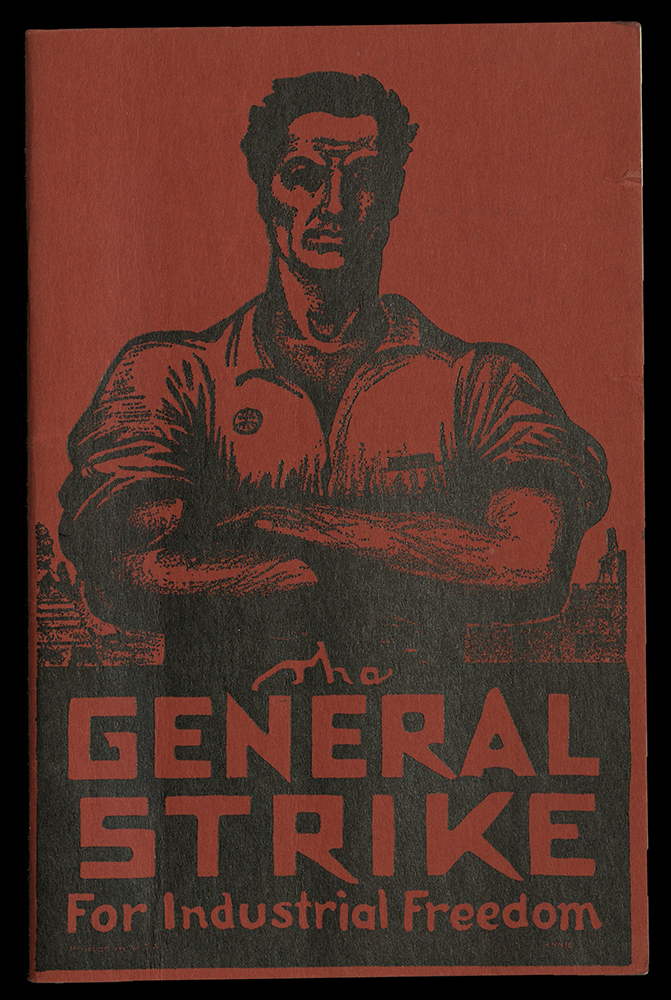

THE GENERAL STRIKE FOR INDUSTRIAL FREEDOM

Industrial Workers of the World

Chicago, IL : Industrial Workers of the World, 1946

HD5307 G46 1946

Reprint of the 1933 pamphlet written by Ralph Chaplin. Chaplin was an American writer, artist and labor activist who was part of the Chicago chapters of the Industrial Workers of the World. For Chaplin, the General Strike meant not simply stopping work but rather moving toward the occupation of industry by the workers themselves. He argued that only worker-controlled industry could combat fascist repression and insure world peace.

In connection to his work with the I.W.W.s, Chaplin and some hundred others were convicted and jailed under the Espionage Act of 1917, for conspiring to hinder the draft and encourage desertion. He served four years of a twenty-year sentence, during which he wrote Bars and Shadows; The Prison Poems. Upon his release, he continued to be active in the I.W.W.s, working as an editor for the Chicago newspaper, the Industrial Worker, from 1932 – 1936. However, he became disillusioned with the evolution of socialism in the Soviet Union, particularly in how it influenced I.W.W. chapters in the United States.

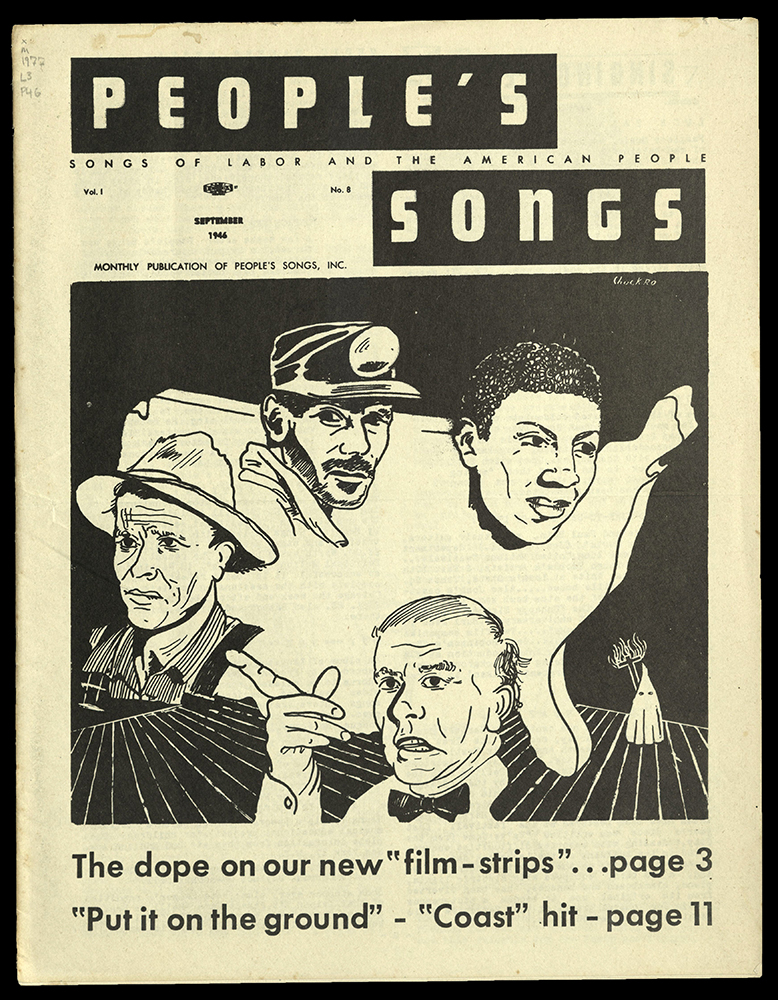

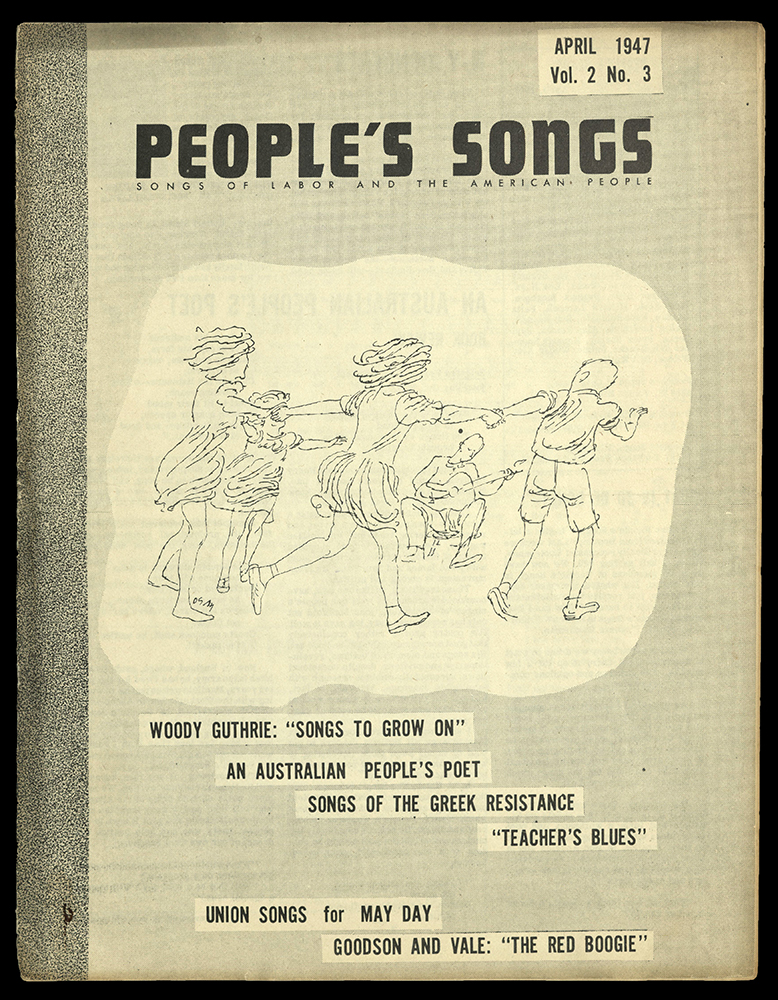

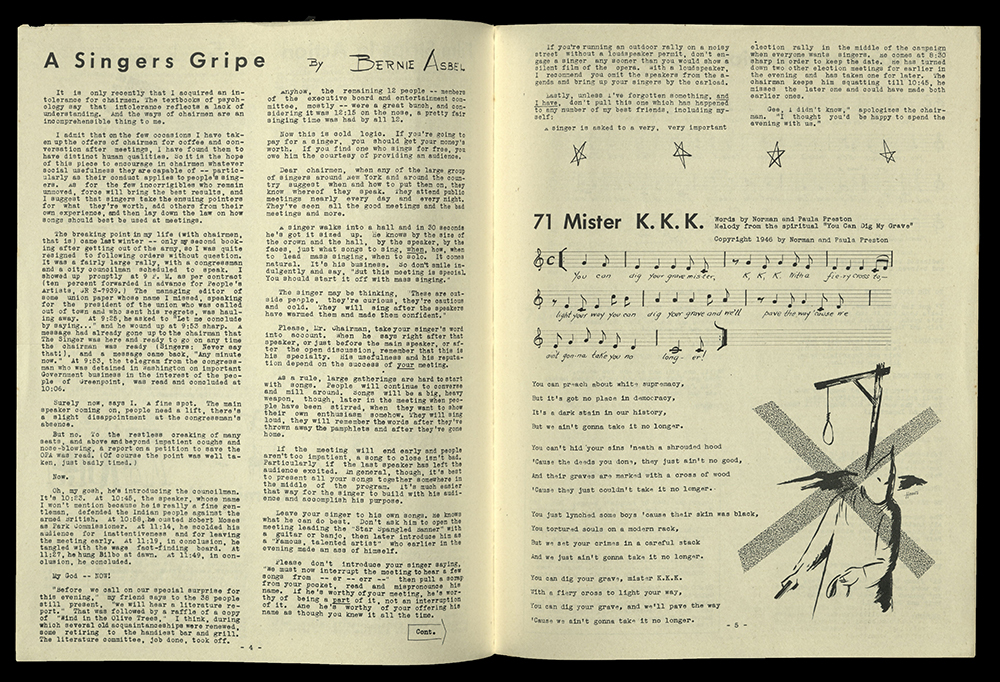

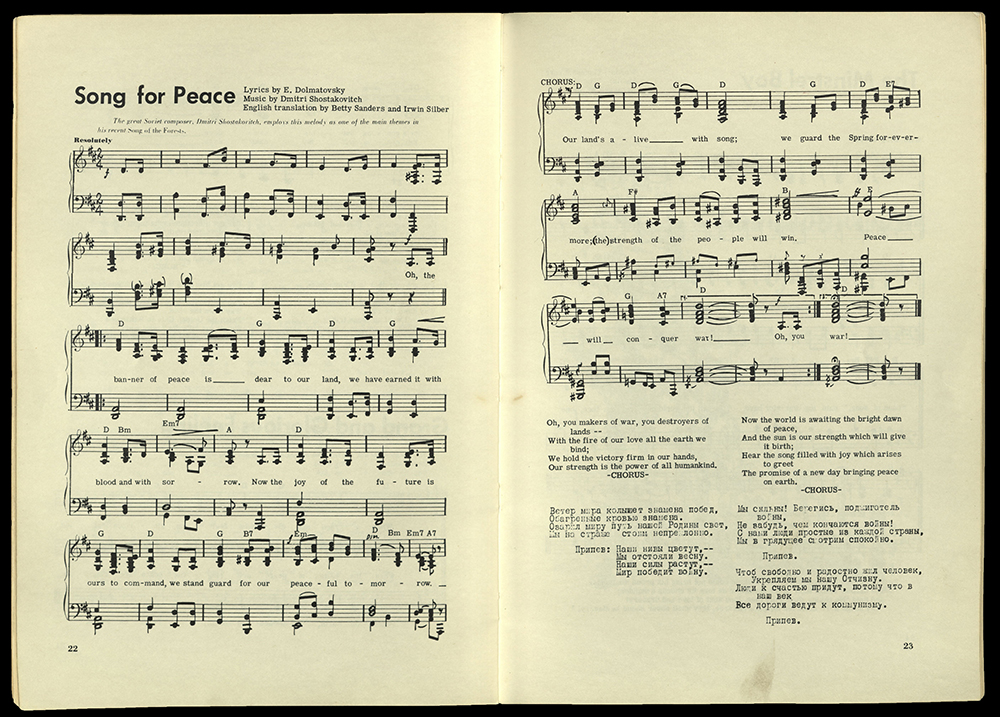

PETE SEEGER : PEOPLE'S SONGS

Pete Seeger (1919 – 2014)

New York, NY : People’s Songs Inc., 1946 -1949

M1977 L3 P46

Pete Seeger was an American folk singer and social activist. He was associated with several musical acts such as The Almanac Singers and The Weavers. Some of his best-known songs include, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”, “If I had a Hammer”, and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” Each of these songs have been recorded by different artists both in and outside the folk revival movement.

During the Second World War, Seeger served in the U.S. Army and was assigned to entertain the troops with music. From his experience, Seeger realized that music could be an effective force for social change. Upon his discharge in 1946, he conceived of an organization to disseminate songs across the country for political action to progressive movements. From this conception, People’s Songs was created. The founding members included several prominent musicians in the folk community, including Woodie Guthrie, Lee Hays, Horace Grenell, Burl Ives, Millard Lampell, Alan Lomax, Josh White, and Tom Glazer. From 1946 to 1950, the organization published a quarterly Bulletin featuring stories, songs, sheet music, and writings, serving as a template for later folk music magazines such as Sing Out! and Broadside.

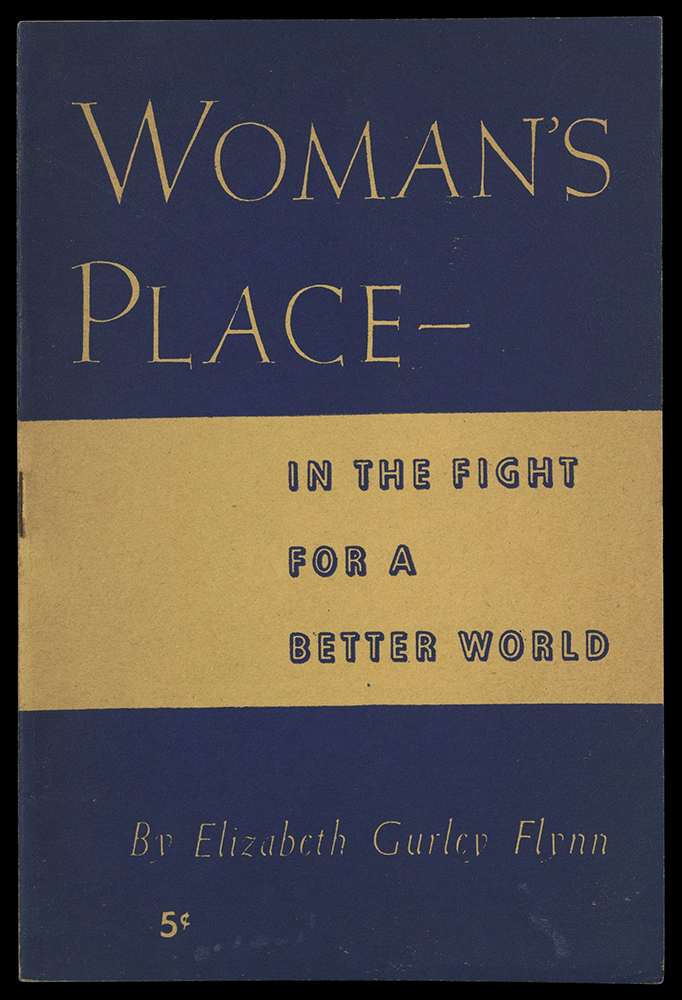

WOMAN'S PLACE — IN THE FIGHT FOR A BETTER WORLD

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York: New Century Publishers, 1947

HQ1426 F72 1947

Women’s Day is celebrated globally on March 8th every year. It’s origins, however, are much closer to home than we might expect. Spurred on by labor and union movements of the early 20th century, the idea for a “women’s day” came out of New York’s lower East Side. In addition to the early strikes and protests of miners, workers in the textile and steel industries also began organizing to demand better working conditions. The growth of labor unions quickly began influencing votes come Election Day, but among those votes one voice was made to keep silent.

In 1908, March 8 was adopted as a day to agitate and demonstrate for the right to vote. Momentum spread quickly and across the globe, reaching the International Socialist Congress in 1910. Held in Copenhagen, delegates from the world unanimously accepted the proposal by German Revolutionary, Clara Zetkin. March 8 was declared International Women’s Day. Among the American delegates was “Big Bill” Haywood, a Salt Lake City native. International Women’s Day was a central point in gaining women’s suffrage.

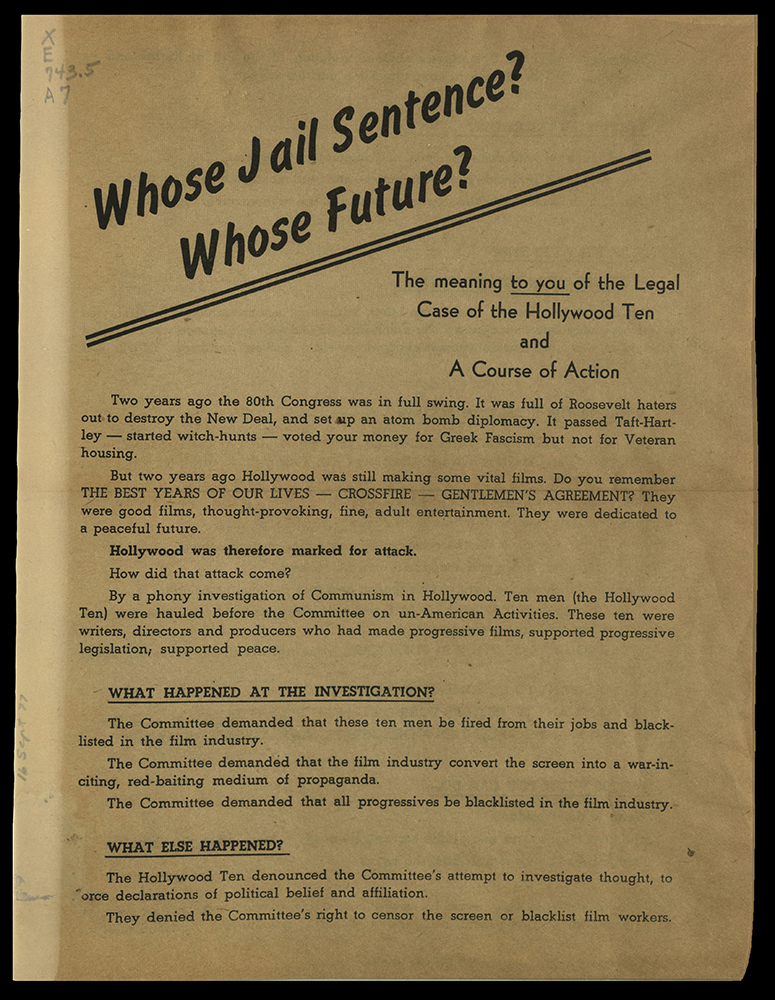

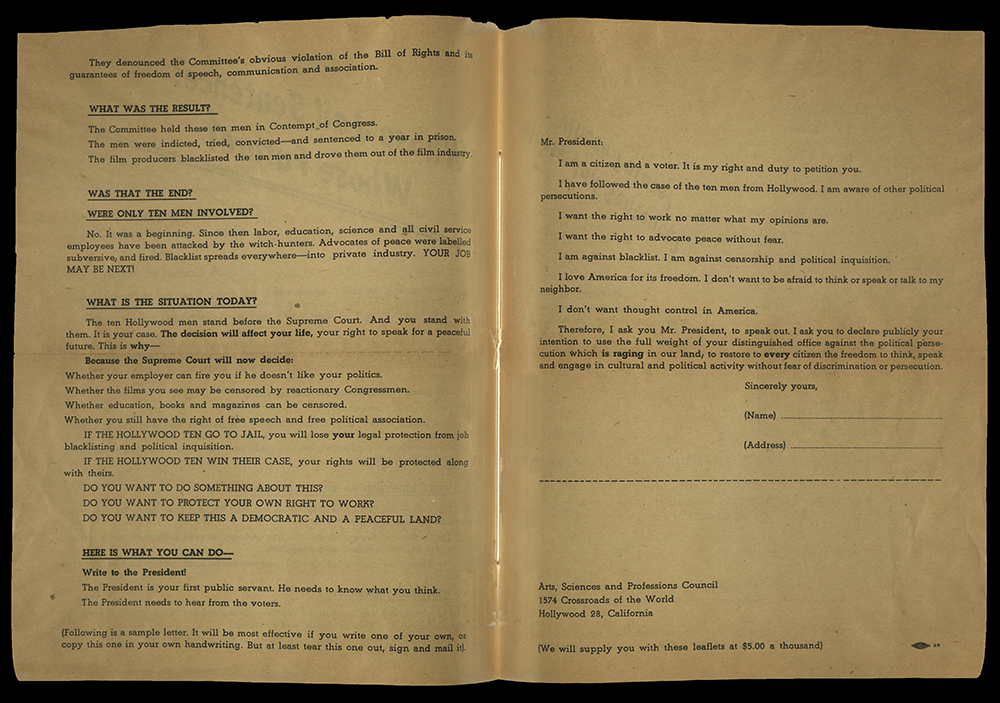

WHOSE JAIL SENTENCE? WHOSE FUTURE?

Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions

Hollywood, CA : Arts, Sciences and Professions Council, 1947?

E743.5 A7

The Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions (ICCASP) was an American association which lobbied unofficially for socialist policies, such as President Roosevelt’s New Deal, and causes pertaining to world peace. In 1947, during the early years of the Cold War, the ICCASP came under attack by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) – established to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and organizations suspected of having Fascist or Communist ties. The ICCASP’s chapter in Hollywood was hit the hardest, due to the high number of members associated with the entertainment industry.

In September 1947, HUAC subpoenaed 79 individuals, claiming that they were subversive and had injected Communist propaganda into their films. The Committee had demanded they admit their political beliefs and name other Communists in the industry. In the end, only ten Hollywood writers and directors appeared before the Committee, although they did so with open indignation and negativity. The Hollywood Ten, as they were called, relied on the First Amendment and argued that belonging to the Communist Party did not constitute a crime. For resisting authority and refusing to answer questions, the Hollywood Ten were cited for contempt of Congress on November 24 1947. The citation included a criminal charge, which led to a highly publicized trial and prompted a group of studio executives to fire the following individuals: Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott, and Dalton Trumbo. Following the congressional hearings was a Hollywood Blacklist, which denied employment to anyone in the entertainment industry who were believed to be Communists or Communist sympathizers. These included not only actors, but also screenwriters, directors, and musicians.

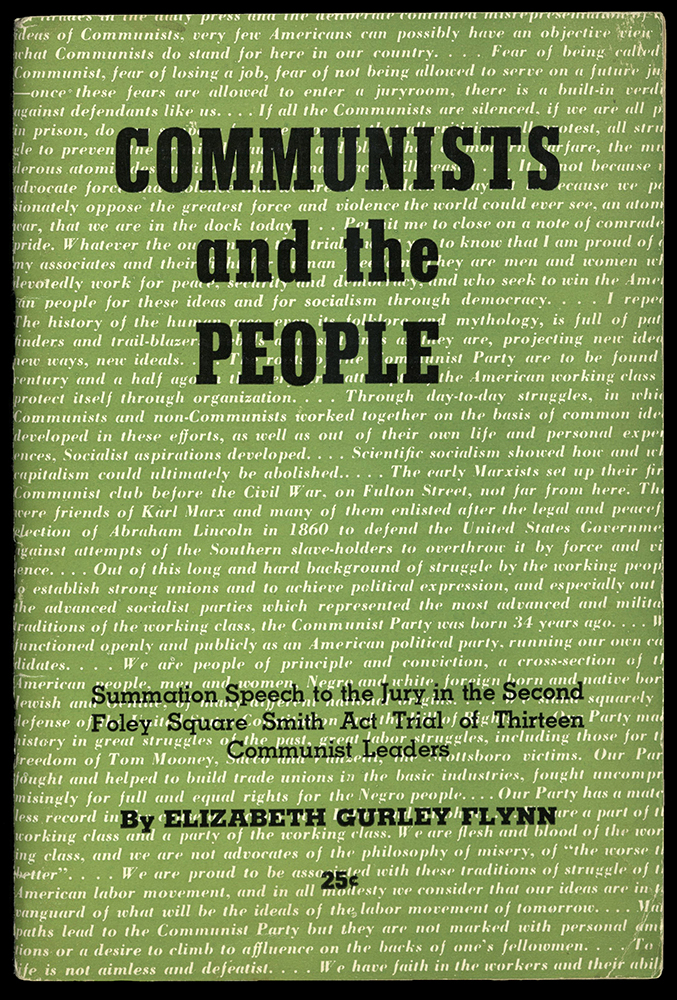

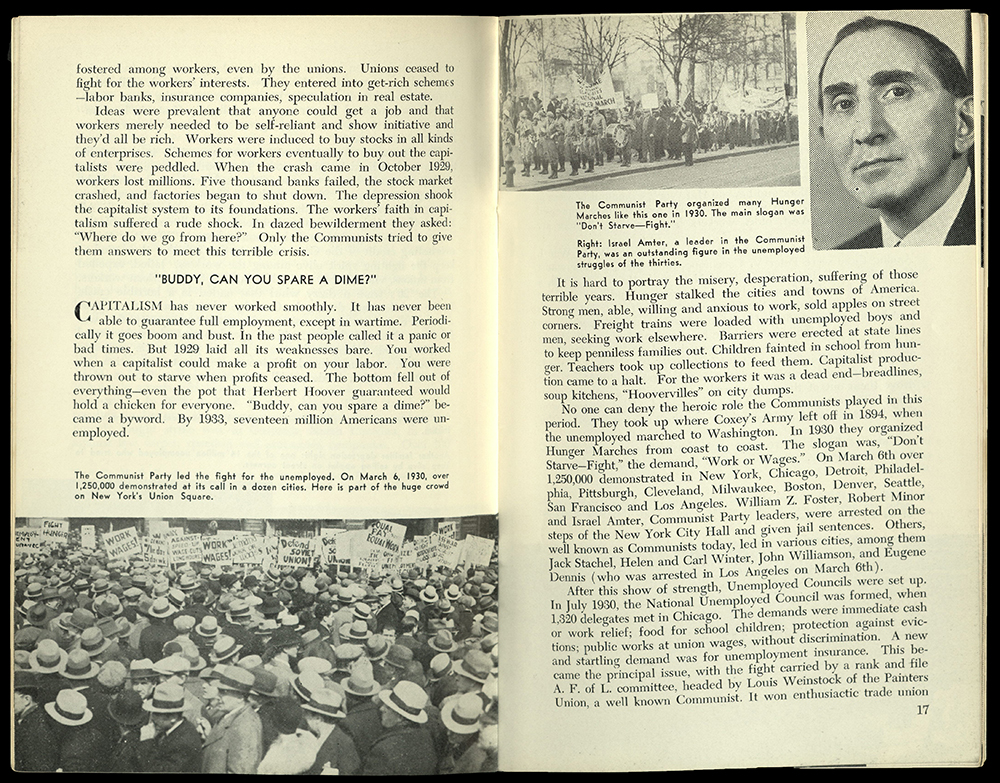

SMITH ACT TRIALS OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY

Almost immediately following WWII, the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union turned, setting the stage for the decades-long Cold War. By 1947, with the tensions intensified, FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, called on the Department of Justice to bring charges against leaders of the Communist Party USA. Hoover’s ultimate goal was to render the party ineffective, hoping to mirror the arrests and convictions of I.W.W. members in 1917. In addition to government persecution, public opinion of communism was overwhelmingly negative, leading to yet another Red Scare. Following orders from Hoover, members of the CPUSA were accused of violating the Smith Act, specifically charging the defendants with conspiring to overthrow the U.S. government by violent means and for belonging to an organization that advocates for the violent overthrow of the government. The indictment, issued on June 29, 1948, asserted that the CPUSA had been in violation of the Smith Act since 1945.

The Smith Act trials of the Communist Party began in 1949, with twelve communist leaders, including Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, Benjamin J. Davis Jr., John Gates, Gil Green, Gus Hall, Irving Potash, Jack Stachel, Robert G. Thompson, John Williamson, Henry Winston, and Carl Winter. This first trial was one of the lengthiest in U.S. history, with the defense continuously antagonizing the judge and prosecution team. Prosecutors used pamphlets and books distributed by CPUSA and interpreted their goals and policies, stating that the texts were examples of their political foundation and were evidence that the party did, in fact, advocate the violent overthrow of the government. The defendants argued against the charges, stating that the CPUSA advocated a peaceful transition to socialism. In addition, they believed that under the First Amendment, they were guaranteed freedom of speech and association, protecting their membership in a political party, whichever that may be. After a ten-month trial, the jury found all twelve defendants guilty, while all five defense attorneys imprisoned for contempt of court – two of which were subsequently disbarred.

Encouraged by their success, prosecutors continued to indict more than more than one hundred additional CPUSA members. However, by 1957, the U.S. Supreme Court brought an end to the prosecutions with the Yates decision, ruling that defendants could only be prosecuted for their actions, not for their beliefs.

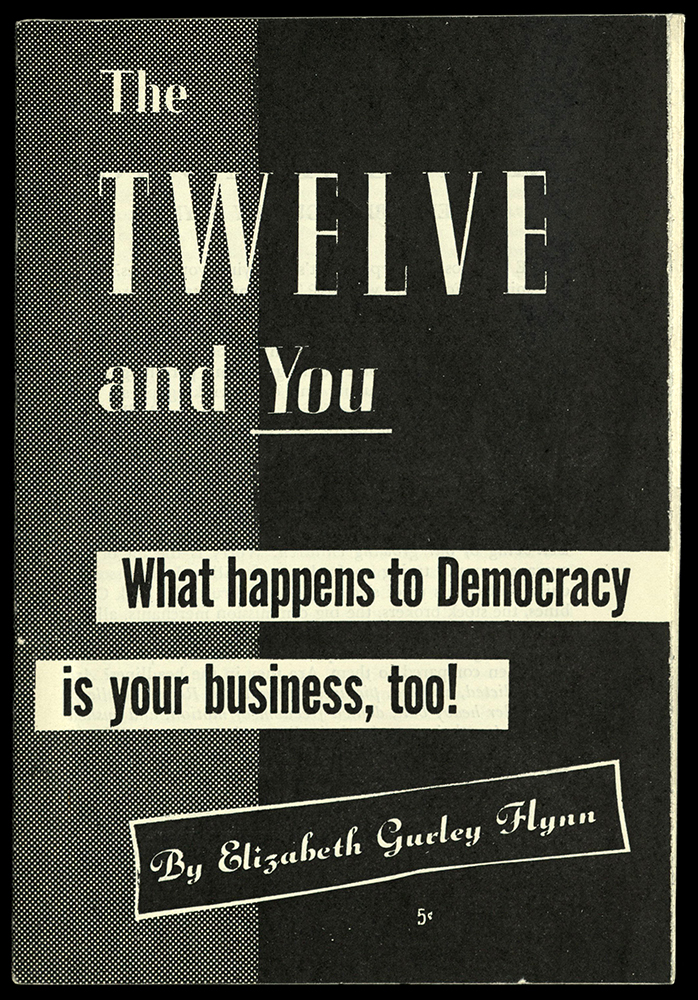

THE TWELVE AND YOU

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : New Century Publishers, 1948

HX87 F548 1948

During the Smith Act trials of the Communist Party USA, New Century Publishers printed dozens of political pamphlets hoping to promote the defense of the twelve communist leaders who were arrested. Many of these pamphlets were written by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a member of the National Committee of the CPUSA, and a veteran leader of the American labor movement. The Twelve and You dissects the charges, exposes the court, and uses the attention given to upcoming trial as an opportunity to publicize CPUSA’s policies.

New Century’s pamphlets encouraged readers to help with its efforts to provide a legal defense team and to give publicity to that defense, whether through literature, radio programs, leaflets, mass meetings, etc. Published and distributed before the set trial date of October 15 1947, The Twelve and You was particularly important as the trial would begin just two weeks and three days before the presidential election. In the pamphlet, Flynn asks the reader, “Can ideas be put in jail? People can, but the whole history of the human race has proved it is impossible to imprison ideas. The crucifixion of Jesus and the violent deaths of all the apostles who preached his works; the torture of Galileo; the exiling of Roger Williams and Anne Hutchison, did not succeed in killing their ides.”

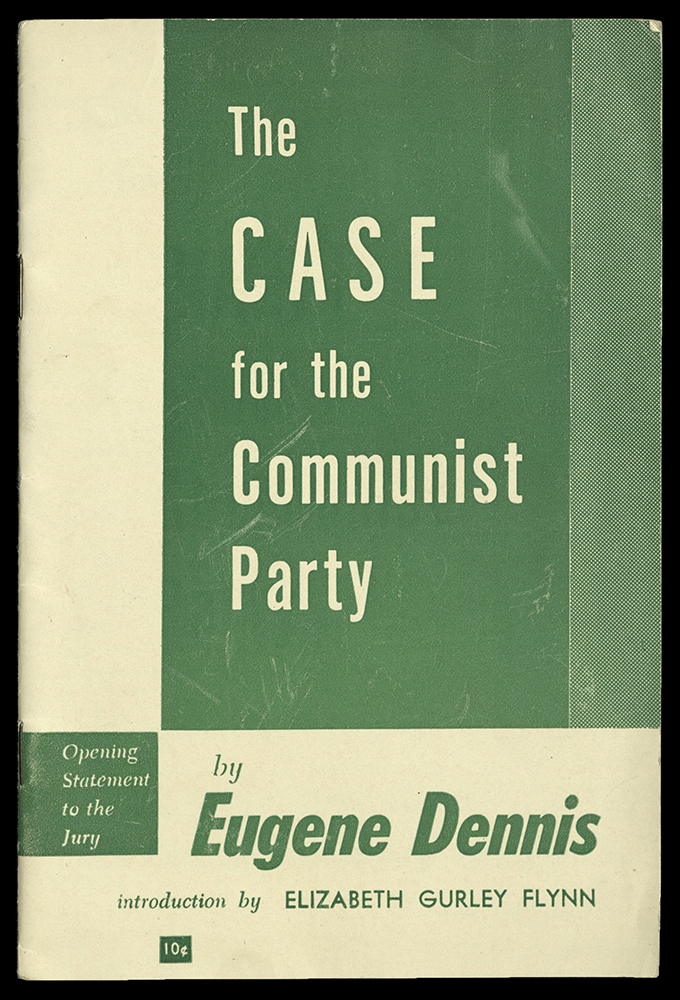

THE CASE FOR THE COMMUNIST PARTY

Eugene Dennis (1905 – 1961)

New York, NY : New Century Publishers, 1949

KF224 C6 D45 1949

Eugene Dennis was one of the twelve communist leaders indicted in the first Smith Act trial against the Communist Party USA in 1948. After the jury found all twelve defendants guilty, Dennis fought to appeal the charges on the grounds that the legislation was unconstitutional and violated the First Amendment. Upon this argument, the Court turned to previous cases, such as Schenck v. United States, Gitlow v. New York, and Whitney v. California, and emphasized that the First Amendment does not protect speech which is used in plotting government overthrow. The Court denied the appeal using the “clear and present danger” test from World War I era sedition cases. The Supreme Court ruled 6-2 against the defendants on June 4, 1951 in Dennis v. United States.

New Century Publishers used the media attention on the trials to promote material from the CPUSA, including essays written by Dennis during the trials and appeals process.

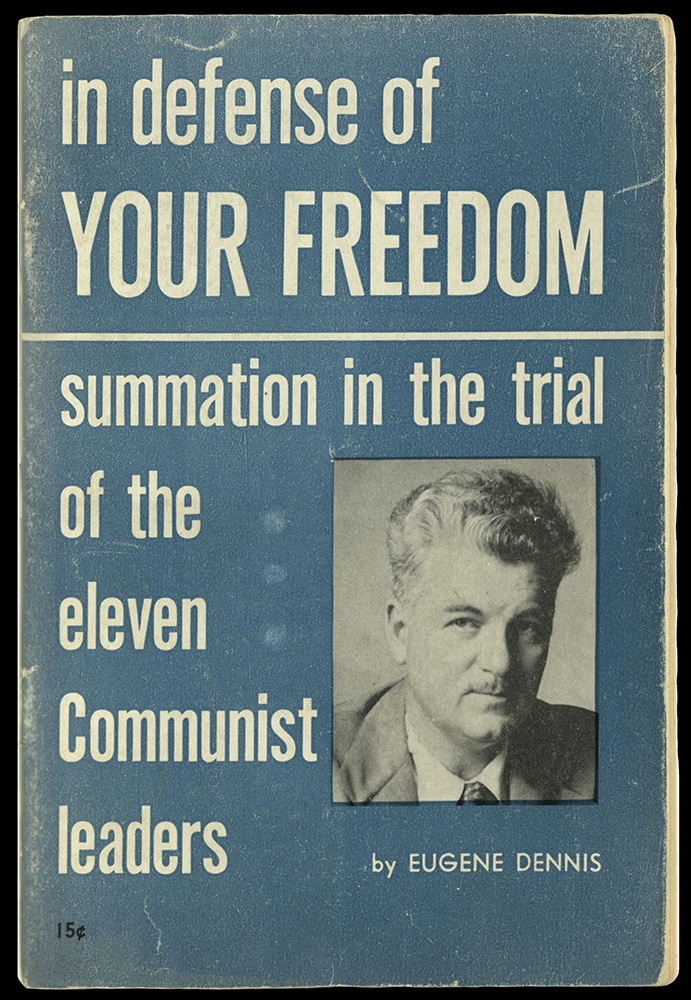

IN DEFENSE OF YOUR FREEDOM

Eugene Dennis (1905 – 1961)

New York, NY : New Century Publishers, 1949

HX92 N5 D4 1949

A summation of the Smith Act trial against Communist Party leader, written by Eugene Dennis, with an introduction by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. From the introduction: "This unprecedented procedure in an American court is not only an attack upon the rights and duty of the legal profession faithfully to defend their clients, but it deprives the defendants, who were rushed to jail without bail, of the indispensable services of the lawyers most familiar with the case to carry forward their appeals.”

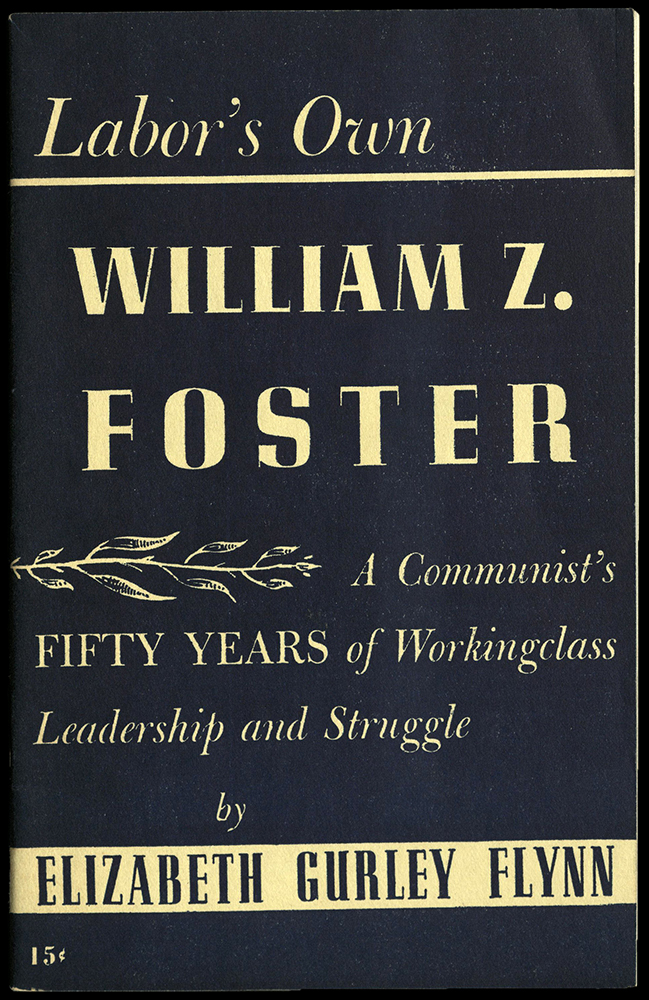

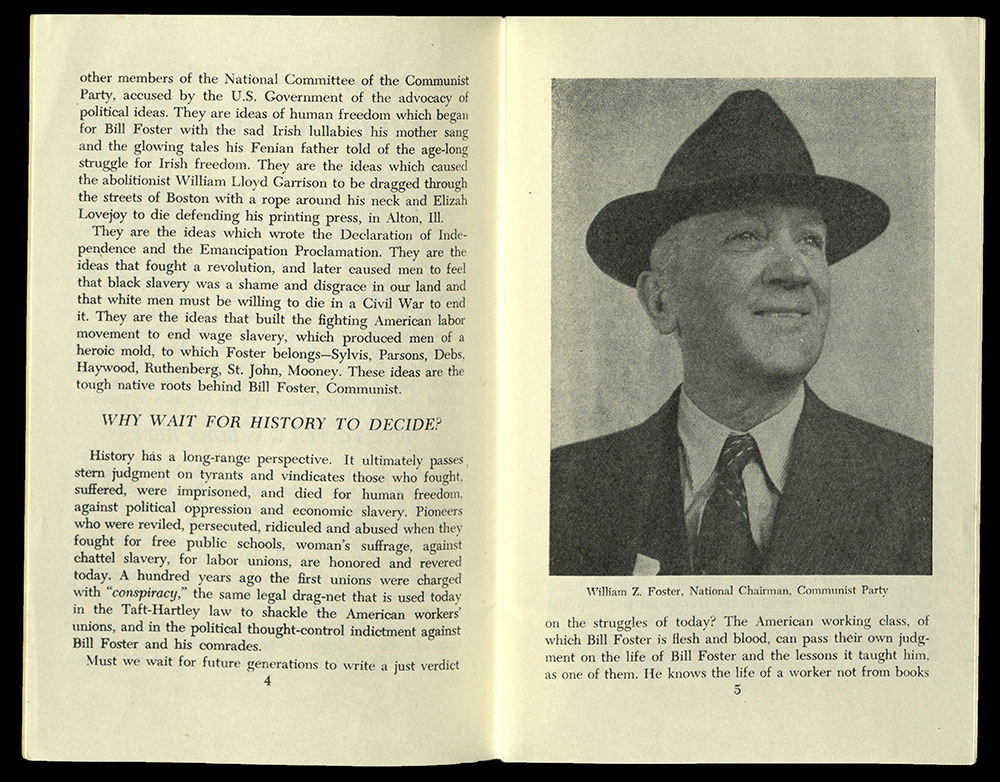

LABOR'S OWN WILLIAM Z. FOSTER

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : New Century Publishers, 1949

HX84 F6 F55 1949

In an effort to persuade public opinion of the Communist Party in the United States during the Smith Act Trials, New Century Publishers distributed dozens of pamphlets which promoted the Party’s socialist policies and highlighted the prominent members who were being persecuted. Written by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Labor’s Own William Z. Foster tells the perilous story of the General Secretary of CPUSA, while emphasizing his poverty, humility, working-class background, and passion for equality and justice. Readers of the pamphlet were invited to join the Communist party in order to honor Foster and help the twelve defendants in the process of appealing their case.

STOOL-PIGEON

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : New Century Publishers, 1949

KF224 C6 F59 1949

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s Stool-pigeon was written in 1949, following the imprisonment of the top leaders in the Communist Party USA. The pamphlet starts by questioning the right of the government to indict the leaders based on the notion of what they are supposed to think. Flynn defines stool-pigeons as “private detectives hired by employers or company agents, despised as ‘finks,’ tools of the bosses, by all honest workers […] Throughout human history there has been scorn and contempt for one who betrays what he pretends loyally to support, and by shamming sincerity gains the confidence of his fellows. Judas Iscariot is the best-known example."

DEBS AND DENNIS, FIGHTERS FOR PEACE

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : New Century Publishers, 1950

HX84 D3 F54 1950

In this pamphlet, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn draws similarities between Communist Party leader, Eugene Dennis, to Socialist activist, Eugene Debs. In addition to their names, both men were sentenced to prison for their political views and for opposing war during peacetime. Debs was convicted for violating the Sedition Act of 1918, while Dennis was convicted on charges under the Smith Act of 1940. Furthermore, both Debs and Dennis defended themselves in court, presenting the jury with moving speeches that were later featured in print.

From the introduction: “Eugene Dennis sits today in a Federal prison cell, for “contempt” of the Un-American Committee. But the real reason he is there is bigger than this disgraceful committee […] Like Eugene Debs, who sat in a prison cell in Atlanta Penitentiary thirty years ago, he is a labor prisoner and a war prisoner. Eugene Dennis is the No. 1 American Prisoner of the cold war, that has now become a shooting war in Korea.”

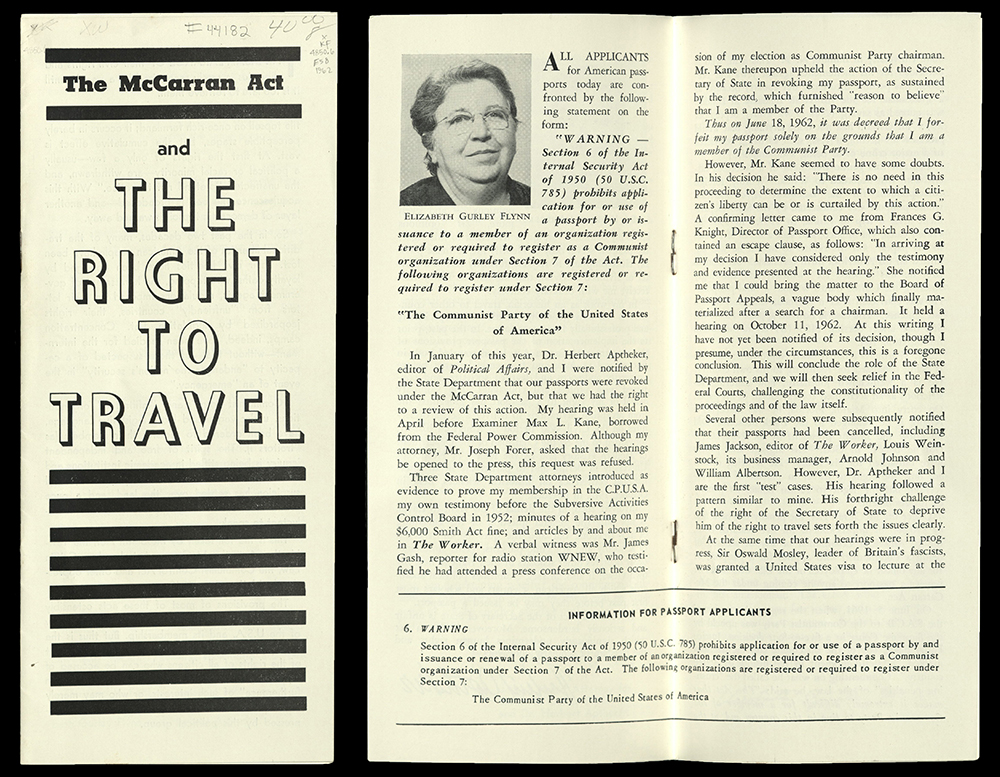

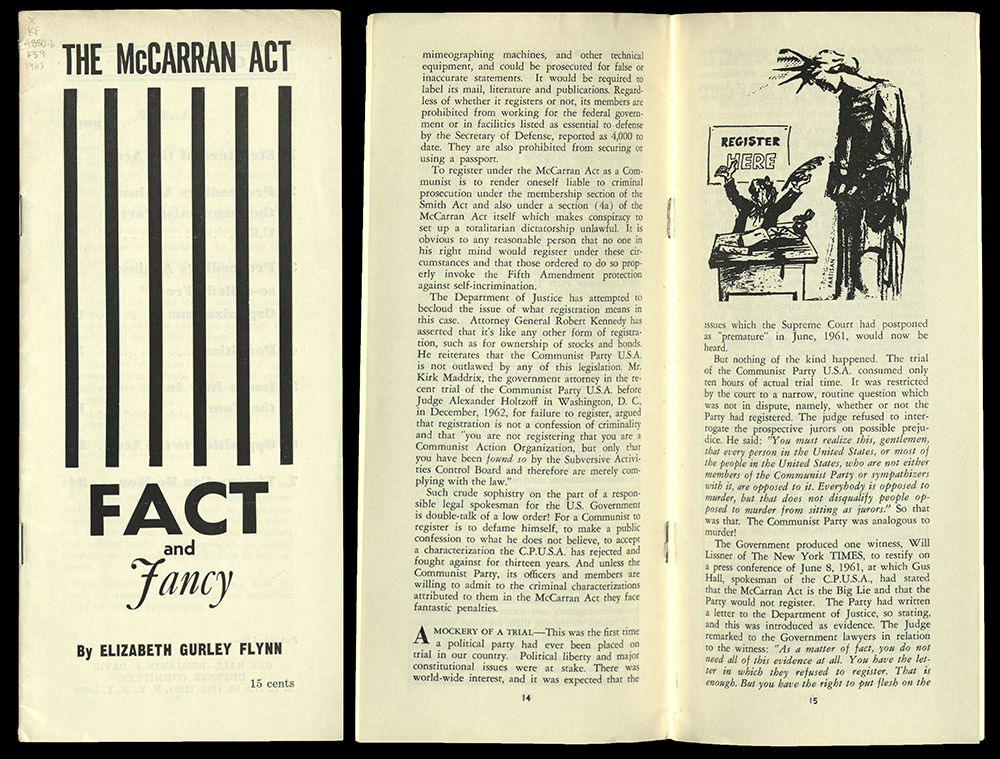

THE MCCARRAN ACT

The Internal Security Act of 1950, also known as The McCarran Act after its principal sponsor, Sen Pat McCarran (D-NV), was enacted by Congress after being vetoed by President Truman. In his veto message, Truman criticized the specific provisions as “the greatest danger to freedom of speech, press, and assembly since the Alien and Sedition Laws of 1798,” emphasizing that it was a “mockery of the Bill of Rights,” and a “long step toward totalitarianism.”

The Act required organizations associated with the Communist Party to register with the United States Attorney General, as well as provide a list of all of its members and reveal the organizations financial records. Once registered, members were liable for prosecution solely based on membership under a continuation of the Smith Act, due to the alleged intent of the organization. The Act also contained an emergency detention statute, giving the President authority to apprehend and detain any person on the grounds that they will “probably engage in, or probably will conspire with others to engage in, acts of espionage or sabotage.”

Furthermore, the McCarran Act increased hostility toward immigrants by tightening alien exclusion and deportation laws. Immigrants who were members of communist groups could not become citizens, and in some cases were prevented from entering or leaving the country. If any immigrant was found in violation of the act within a five-year period of being naturalized, citizenship could be revoked. This had severe implications for thousands of immigrants displaced by WWII, and within a year of the legislation having passed, the McCarran Act had excluded 54,000 people of German origin and 12,000 Russians.

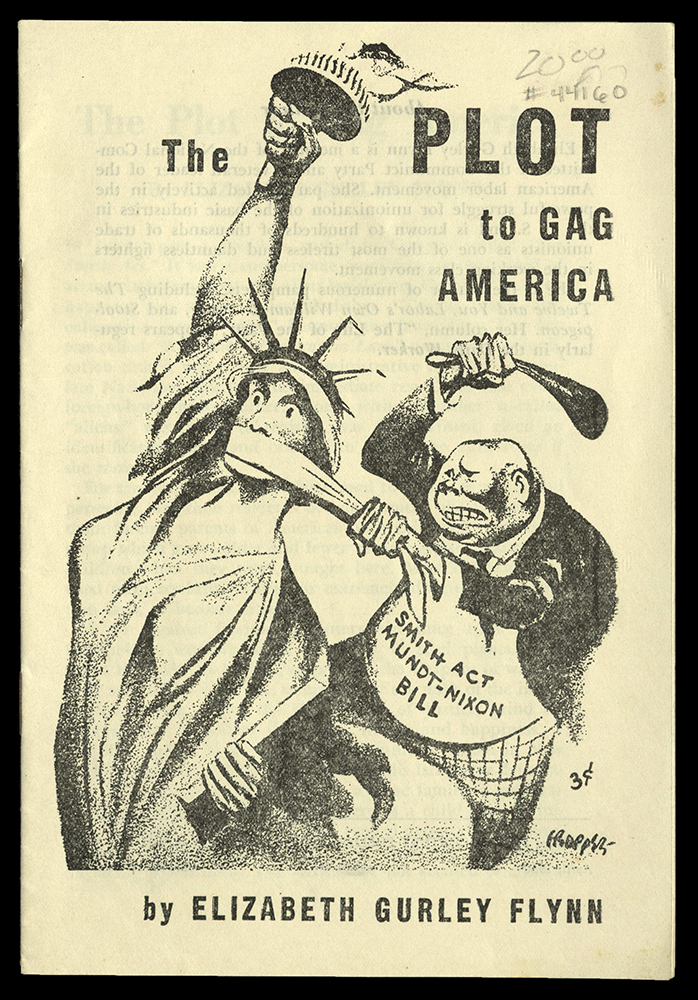

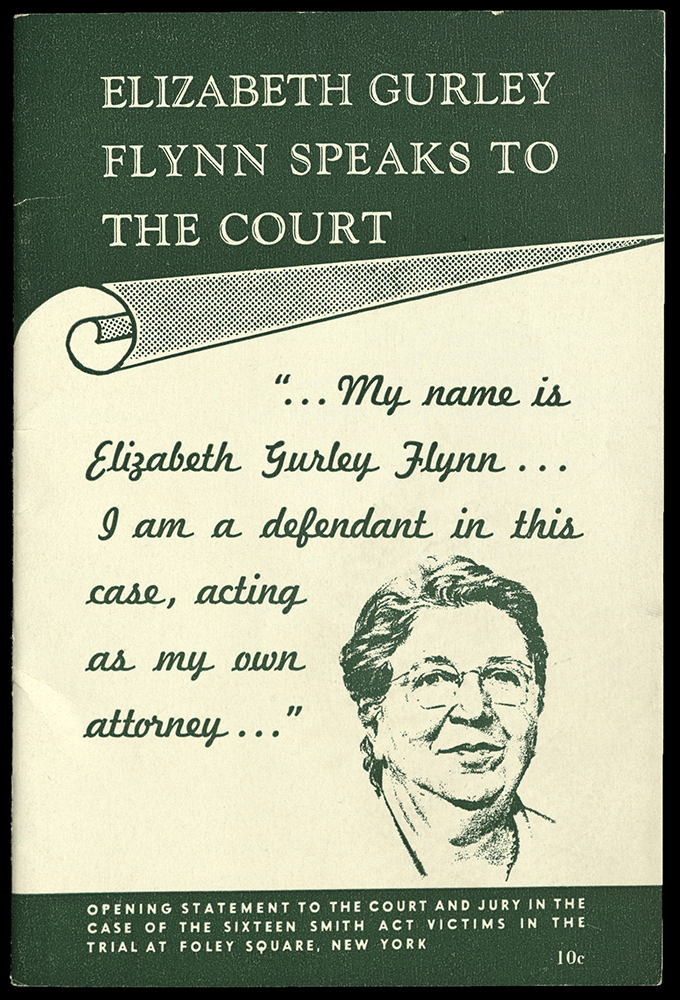

THE PLOT TO GAG AMERICA

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (1890 – 1964)

New York, NY : New Century Publishers, 1950

K3275 F48 1950